HMSNEWS Gill Juleff and Matthew Baker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There's Metal in Those Hills Sheffield Was Once the Iron, Steel and Cutlery

There’s Metal in Those Hills Sheffield was once the iron, steel and cutlery capital of the world. The hills around Sheffield and Rotherham were full of raw materials like coal and iron ore that could be used in cutlery and blade production. Before we were Famous Sheffield and Rotherham became famous for manufacturing and production for four main reasons: crucible steel, stainless steel, electroplating and cutlery. Crucible Steel Benjamin Huntsman invented the crucible steel process. Before this process was invented, the quality of the steel was unreliable and slow to produce. Benjamin Huntsman’s invention allowed people to produce tougher, high-quality steel in larger quantities. Stainless Steel Harry Brearley began testing why rifles rusted and exploring ways to stop steel from rusting. He developed Stainless Steel which was much more rust resistant than the steel that had been used previously. Cutlery Sheffield and Rotherham have been connected to the production of cutlery since the 1600s. Sheffield was the main center of cutlery production in England outside of London. Sheffield became world famous for its production of high-quality cutlery. The moving story of Sheffield’s remarkable Women of Steel Yorkshire Post article 13th June 2020 The story of Kathleen, one of the last surviving Sheffield steelworkers from the war. When war broke out, the lives of the young women of Sheffield were turned upside down. With the men sent away to fight they had no choice but to step into their shoes and became the backbone of the city’s steel industry. Through hard graft and companionship in the gruelling, and often dangerous world of factory work, they vowed to keep the foundry fires burning. -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume One THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SHEFFIELD AND THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN cl740-c 1820 Neville Flavell February 1996 SUMMARY In the early eighteenth century Sheffield was a modest industrial town with an established reputation for cutlery and hardware. It was, however, far inland, off the main highway network and twenty miles from the nearest navigation. One might say that with those disadvantages its future looked distinctly unpromising. A century later, Sheffield was a maker of plated goods and silverware of international repute, was en route to world supremacy in steel, and had already become the world's greatest producer of cutlery and edge tools. How did it happen? Internal economies of scale vastly outweighed deficiencies. Skills, innovations and discoveries, entrepreneurs, investment, key local resources (water power, coal, wood and iron), and a rapidly growing labour force swelled largely by immigrants from the region were paramount. Each of these, together with external credit, improved transport and ever-widening markets, played a significant part in the town's metamorphosis. Economic and population growth were accompanied by a series of urban developments which first pushed outward the existing boundaries. Considerable infill of gardens and orchards followed, with further peripheral expansion overspilling into adjacent townships. New industrial, commercial and civic building, most of it within the central area, reinforced this second phase. A period of retrenchment coincided with the French and Napoleonic wars, before a renewed surge of construction restored the impetus. -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

ARCHAEOLOGY DATASHEET 302 Steelmaking

ARCHAEOLOGY DATASHEET 302 Steelmaking Introduction A single forging produced ‘shear steel’, a second operation Although an important aspect of medieval and earlier resulted in ‘double shear steel’ and so-on. societies, the manufacture of steel was industrialised during Furnace design changed over time, and also appears to the post-medieval period. Many complementary techniques have shown some regional variation. The first English steel were developed which often operated at the same time on furnaces were built at Coalbrookdale (Shropshire) by Sir the same site; there were also close links with other Basil Brooke in c1615 and c1630. These were circular in ironworking processes. This datasheet describes pre-20th plan with a central flue. They probably contained a single century steelmaking processes in the UK, their material chest and would have had a conical chimney. Other 17th- remains and metallurgical potential. century cementation furnaces were located in and around Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Stourbridge and Bristol, but Carbon steel and other alloys none of these have been excavated. The north-east became Until the late 19th century, steel was, like other types of the main area of cementation steelmaking in the late 17th iron, simply an alloy of iron and carbon (HMS datasheet and early 18th centuries. Ambrose Crowley established 201). There was considerable variation in the nature of several cementation steelworks, and others followed. Of ‘steel’ and in the properties of individual artefacts. Cast these, the oldest standing structure is at Derwentcote iron, smelted in the blast furnace usually had a carbon (County Durham), built in 1734. Unlike the West Midlands content of 5-8%, making it tough but brittle. -

Sheffield City Council

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL - BUILDINGS AT RISK BY CATEGORY No Name G Last/Current Notes Use RELIGIOUS BUILDINGS/CEMETERY STRUCTURES 1 Roman Catholic mortuary chapel, City Road cemetery II Chapel 2 Blitz grave, City Road cemetery II Monument 3 Tomb of Benjamin Huntsman, Attercliffe Chapel, Attercliffe Common II Monument 4 Salvation Army Citadel, Cross Burgess Street II Religious Part of the New Retail Vacant Quarter. Appeal lodged against refusal of lbc for conversion. 5 St Silas Church II Religious LBC granted for conversion Vacant to offices and health centre 2005 6 Anglican Chapel, SGC II Religious LBC refused 2007 – lack of Vacant information 7 Non Conformist Chapel, SGC II Religious Leased to FOSGC Vacant 8 Catacombs at SGC II* Monument Leased to FOSGC 9 Loxley Chapel II* Religious Pre-app meeting held. Vacant Application expected 09 10 Crookes Valley Methodist Church II Religious LBC application received Vacant Dec 2007. To be monitored. 11 James Nicholson memorial, SGC II Monument 12 Former Middlewood Hospital Church II Religious To be monitored Vacant Needs new use. 13 Walsh Monument, Rivelin Cemetery II Monument METAL TRADES BUILDINGS 14 286 Coleridge Road, Crucible steel melting shop II Workshop 15 East range, Cornish Place Works, Cornish Street II Workshop Awaiting repairs by owner. Pre-app meetings ongoing. 16 Darnell Works south workshop II* Workshop Darnell Works – south east workshop II* Darnell Works - weighbridge II Darnell Works - offices II 17 Grinding hull, forge, assembly shop. 120a Broomspring Lane II Workshop LBC granted -

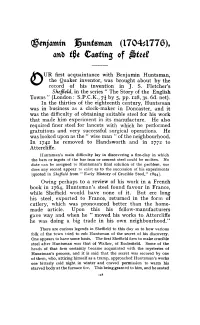

Benjamin Huntsman, the Quaker Inventor, Was Brought About by the O Record of His Invention in J

njamitt guttteman (1704*1776), of UR first acquaintance with Benjamin Huntsman, the Quaker inventor, was brought about by the O record of his invention in J. S. Fletcher's Sheffield, in the series " The Story of the English Towns " (London : S.P.C.K., 7^ by 5, pp. 128, 35. 6d. net). In the thirties of the eighteenth century, Huntsman was in business as a clock-maker in Doncaster, and it was the difficulty of obtaining suitable steel for his work that made him experiment in its manufacture. He also required finer steel for lancets with which he performed gratuitous and very successful surgical operations. He was looked upon as the " wise man " of the neighbourhood. In 1742 he removed to Handsworth and in 1772 to Attercliffe. Huntsman's main difficulty lay in discovering a fire-clay in which the bars or ingots of the bar iron or cement steel could be molten. No date can be assigned to Huntsman's final solution of the problem, nor does any record appear to exist as to the succession of his experiments [quoted in Sheffield from " Early History of Crucible Steel," 1894], Owing perhaps to a review of his work in a French book in 1764, Huntsman's steel found favour in France, while Sheffield would have none of it. But ere long his steel, exported to France, returned in the form of cutlery, which was pronounced better than the home made article. Upon this his fellow-manufacturers gave way and when he " moved his works to Attercliffe he was doing a big trade in his own neighbourhood." There are curious legends in Sheffield to this day as to how various folk of the town tried to rob Huntsman of the secret of his discovery. -

The Impact of the Iron and Steel Industry to Karabük and Sheffield: a Historical Background**

Journal of Corporate Governance, Insurance, and Risk Management (JCGIRM) 2016, Volume 3, Series 2 PP109-125 The Impact of the Iron and Steel Industry to Karabük and Sheffield: A Historical Background** Can Biçer,a, , Kemal Yamanb * aKarabük University, Safranbolu Vocational School, Safranbolu, Karabük, TURKEY bKarabük University,Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Karabük, TURKEY A B S T R A C T A R T I C L E I N F O In this study, the two cities, Sheffield in the UK and Karabük in Turkey, Keywords:Karabük, Sheffield, which are famous for iron and steel producing, were analyzed through their Iron and Steel Production, Urban historical background to focus on the differences and similarities from an development urban perspective. Both the rise in the production of iron and steel in the *Corresponding author: 18th century through Industrial Revolution and the innovations made [email protected] Sheffield popular throughout the world. Karabük is called “The Republic City” in Turkey because the first iron and steel works were built in Karabük Article history: in 1937 shortly after the proclamation of Republic of Turkey. The museums were visited and the local studies and academic papers were sorted out to Received 22 03 2016 see the effects of sudden changes which the heavy industry caused in the Revised 25 04 2016 cities and it’s concluded that the industrial, urban and social experiences of Accepted 27 7 2016 Sheffield may be a guide for Karabük. **Previously Published in EJEM, 2016, Volume 3 number 2 1. INTRODUCTION The Industrial Revolution began in England sometime after the middle of the 18th century. -

Robert Sorby and Sons

Robert Sorby and Sons Written by the Company and published by HAND TOOL PRESERVATION ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC. The origins and history of Robert Sorby and Sons Limited, supplemented with notes about other Sheffield toolmakers with the name Sorby. 3 Sheffield Sheffield is located a little north of the centre of England, roughly 250 kilometres north of London, 120 kilometres north of Birmingham, and 300 kilometres south of Edinburgh and Glasgow. For more than 100 years Robert Sorby and Sons operated from premises near the centre of Sheffield. The Company set up in Union Street in 1828. In 1837 it moved to nearby Carver Street. About 1896 it moved a short distance to the corner of Trafalgar and Wellington Streets. Since 1934 it has been located a few miles south of the centre of the city. Union Street, where the Company began business, may have been where the City Hall is now (marked C on the map). Central Sheffield 2 Robert Sorby & Sons Robert Sorby & Sons Robert Sorby is one of the world’s premier manufacturers of specialist woodworking tools, with a proud heritage dating back more than 200 years. During that time Robert Sorby has developed a global reputation for manufacturing some of the finest edge tools available. We at Robert Sorby proudly continue this manufacturing tradition form our base in Sheffield, England where today Robert Sorby is one of the city’s oldest manufactures. For more on the history of Robert Sorby read this flip through booklet. Robert Sorby would like to thank all at the Hand Tool Preservation Association of Australia for compiling this historical account of Robert Sorby. -

The Legend of Benjamin Huntsman and the Early Days of Modern Steel

FEATURES HISTORICAL NOTE The legend of Benjamin vats of molten iron. Coke was also bet- ter than charcoal at reducing iron oxide in Huntsman and the early steel production. Though first applied to the manufacture of steel as early as 1709, days of modern steel coke wouldn’t be in vogue for steelmak- ing until production methods gradually im- By Omar Fabián proved in the following decades. Shards of glass, meanwhile, were the t was a cold winter night in Sheffield, Samuel Walker made indescribably rapid secret sauce in Huntsman’s recipe. When IEngland, when a cloaked beggar strides in producing crucible steel within added to the crucibles that hosted the knocked on the doors of the local steel a suspiciously short time. And in mid-18th steelmaking reaction, glass would soak foundry seeking shelter. The benevolent century Sheffield, England, enterprising up impurities from the molten metal and crew took pity on the man and ushered craftsmen would go to almost any lengths then be skimmed off the surface after fir- the stranger in, offering the warm shop to gain a foothold in the burgeoning and ing. It was, according to Huntsman family floor as makeshift quarters for the night. lucrative market for high-quality steel. lore, the step Samuel Walker most desired But a closer look at the self-described Benjamin Huntsman never set out to be- to glimpse that Sheffieldian winter night. “tramp” would have revealed him to come the famed inventor of modern steel Walker was hardly the only one to resort be no stranger or beggar. -

'One Great Workshop': the Buildings of the Sheffield Metal Trades

'ONE GREAT WORKSHOP': THE BUILDINGS OF THE SHEFFIELD METAL TRADES © English Heritage 2001 Text by Nicola Wray, Bob Hawkins and Colum Giles Photographs taken by Keith Buck, Tony Perry and Bob Skingle Aerial photographs taken by Pete Horne and Dave MacLeod Photographic printing by Keith Buck Drawings by Allan T Adams Maps by Philip Sinton Survey and research undertaken by Victoria Beauchamp, Keith Buck, Garry Corbett, Colum Giles, Gillian Green, Bob Skingle and Nicola Wray Edited by Rene Rodgers and Victoria Trainor Designed by Michael McMann, mm Graphic Design Printed by Westerham Press ISBN: 1 873592 66 3 Product Code: XC20053 English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. 23 Savile Row London W1S 2ET Telephone 020 7973 3000 www.english-heritage.org.uk All images, unless otherwise specified, are either © English Heritage or © Crown copyright. NMR. Applications for the reproduction of images should be made to the National Monuments Record. Copy prints of the figures can be ordered from the NM R by quoting the negative number from the relevant caption. The National Monuments Record is the public archive of English Heritage. All the research and photography created whilst working on this project is available there. For more information contact NMR Enquiry and Research Services, National Monuments Record Centre, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ. Telephone 01793 414600 Sheffield City Council made a financial contribution towards the publication of this book. ‘ONE GREAT WORKSHOP’: THE BUILDINGS -

The White Book of STEEL

The white book of STEEL The white book of steel worldsteel represents approximately 170 steel producers (including 17 of the world’s 20 largest steel companies), national and regional steel industry associations and steel research institutes. worldsteel members represent around 85% of world steel production. worldsteel acts as the focal point for the steel industry, providing global leadership on all major strategic issues affecting the industry, particularly focusing on economic, environmental and social sustainability. worldsteel has taken all possible steps to check and confirm the facts contained in this book – however, some elements will inevitably be open to interpretation. worldsteel does not accept any liability for the accuracy of data, information, opinions or for any printing errors. The white book of steel © World Steel Association 2012 ISBN 978-2-930069-67-8 Design by double-id.com Copywriting by Pyramidion.be This publication is printed on PrintSpeed paper. PrintSpeed is certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council as environmentally-responsible paper. contEntS Steel before the 18th century 6 Amazing steel 18th to 19th centuries 12 Revolution! 20th century global expansion, 1900-1970s 20 Steel age End of 20th century, start of 21st 32 Going for growth: Innovation of scale Steel industry today & future developments 44 Sustainable steel Glossary 48 Website 50 Please refer to the glossary section on page 48 to find the definition of the words highlighted in blue throughout the book. Detail of India from Ptolemy’s world map. Iron was first found in meteorites (‘gift of the gods’) then thousands of years later was developed into steel, the discovery of which helped shape the ancient (and modern) world 6 Steel bEforE thE 18th cEntury Amazing steel Ever since our ancestors started to mine and smelt iron, they began producing steel. -

The Use of Steel Castings in Mechanical and Civil Engineering – Germany

THE USE OF STEEL CASTINGS IN MECHANICAL AND CIVIL ENGINEERING – GERMANY. 1850-1950 Volker Wetzk1 Keywords Steel Castings, Cast Steel, Bridge Bearings Abstract In contrast to other historic building materials such as cast and wrought iron or rolled steel, historic steel castings have been widely neglected in the technical literature dealing with con- struction history. Indeed, steel castings represent only a minor part within historic structures. However, steel castings were often used for crucial structural elements with high demands in terms of structural safety, durability and other such factors in the field of mechanical and civil engineering. Propellers for engines and bearings for bridges may serve as examples to name but a few. This paper deals with historic steel castings produced in the years between 1850 and 1950 and used for structural purposes in mechanical and civil engineering. After a brief summary of the history of steel castings fabrication, the paper focuses its engineering use and refers to specif- ic mechanical properties and chemical compositions. The appropriation of historic steel castings as a material for bridge bearings is especially emphasized and compared to that of contemporary state-of-the-art of steel castings’ use in mechanical engineering. This analysis yields insights into the stage of the metallurgical development in the case of steel castings and broadens the base for their structural assessment. The research is based on findings from a recent research project to provide options for the preservation of historic bridge bearings made of steel and still in use. The project, a co-operation between the Brandenburgische Technische Universität and the Bundesanstalt für Material- forschung und -prüfung, was being funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).