IX Overseas and France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being the "Log" of the U.S.S. Maui in the World War : with Photographic Illustrations

^% ofihe v^y^MAvi ^n ihe World Wiar GIFT OF A. F. Morrison *H%wi,a.\rtn \9b«;U Ottl^ ^mJk. tX^\>»^>n^€^\^ M|^ au^*Jc;^^^\w;^ Wow*. %Ji;.JL. woe ^ JIAIk .j^^^X^m-^ a3w^ o-dtti Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/beinglogofussmauOOmauirich TT\aJjjXb.3.Shjuo BEING THE "LOG" of the U.S. S. Maui In the World War WITH PHOTOGRAPHIC ILLUSTRATIONS Compiled by Lieutenant W. E. Hennerich, MC. - - U.S.N. Lieutenant J. W. Stewart - - - U.S.N.R.F. Lieutenant(j.g.)Wm. P. Reagor, Chaplain - U.S.N. J. F. McKenna, Yeoman, first class - - U.S.N. B. F. Johnson, Yeoman, third class - - U.S.N. H. G. Binder, Ptr., second class, Cartoonist - U.S.N. BY PERMISSION OF THE COMMANDING OFFICER X)570 'i4- GIFT OF . c c c c c c c c c To W. F. M. EDWARDS '*Our Skipper"' M94379 A truer, nobler, trustier heart, more loving, or more loyal, never beat within a human hrezst.-BYRON. LlEUTENAXT-CoMMANDER, U.S.N.R.F. Commanding Officer — ^^HE name of our good ship, Maui, was, perhaps, -' -^ ' to most of us the most strange and meaningless of any of the ships in this fleet, and upon first seeing it in print no doubt it seemed unpro- nounceable. Yet the name has a romance about it that one associates with the sea, for the ship was named after the beautiful Island of Maui, the second largest of the Hawaiian group. The purpose of our book is to tell in a simple and short manner, and so that we may keep it fresh in our memories in the years to come, the tale of the part played in the great war by the good ship Maui and the men who manned her. -

The Foreign Service Journal, June 1925

THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL Photo from E. L. Harris. A SCENE AT THE RUINED CITY OF APHRODISIAS JUNE, 1925 FEDERAL-AMERICAN NATIONAL BANK NOW IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION IN WASHINGTON, D. C. W. T. GALLIHER, Chairman of the Board JOHN POOLE, President RESOURCES OVER $13,000,000.00 ME FOREIGN S JOURNAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION VOL. II No. 6 WASHINGTON, D. C. JUNE, 1925 Aphrodisias By ERNEST L. HARRIS, Consul General, Vancouver ASIA MINOR is the stage upon which have before the dawn of history there are even Hit- been enacted some of the most stupen¬ tite, Phrygian, Lydian, and Greek ruined cities dous events in the history of mankind. left to tell the tale. From the time when Mardonius first crossed the Of all the ruined cities in Asia Minor—and I Hellespont down to the days of the have seen them all—Aphrodisias Anzacs is a goodly span of years, is the most interesting. It is vet every century of it has been also the best preserved because rendered luminous by Persian and it was outside the great Persian Greek, Roman and Pontian, Byzan¬ and Greek highways which tine and Moslem, Crusader and traversed the Hermus and Saracen, Turk and Mogul. The Meander valleys. This accounts graves of Australian soldiers almost for the fact that it was never within sight of the walls of Troy destroyed. The Salbaccus attest the latest scene of strife upon mountain range protected it this stage of apparently never end¬ from invading armies. The ing drama. Fading into the sable ruins are those produced by the mists of the past is the present hand of time rather than by the melancholy picture of ruined cities hand of man. -

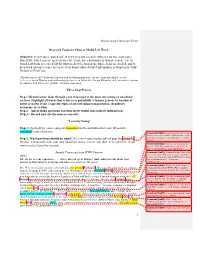

Punch List” of Key Terms and Research Strategies for the Essay Paper

Researching Transcript Terms Research Tasks for Class & Media Lab Work Objective: to develop a “punch list” of key terms and research strategies for the essay paper. Hopefully, your terms are spelled correctly. If not, use a dictionary or Google search. Use the Punch List Form as a check list for what needs to be looked up, where items are located, and to keep track of sources once they have been found. More detailed information is found in the OHP Manual on FirstClass. [Noodle tools or 2007 Word will help you with the bibliography later. For the technically skilled, use the „references‟ tab in Word to work with managing sources, to follow the Chicago Manual of style, or to insert citations or endnotes. You will receive guidance on this in class, too.] Three Step Process Step 1 Identification: skim through your transcript to the most interesting or anecdotal sections. Highlight all words that relate to a) potentially a famous person, b) location of battle or battle event, c) specific types of aircraft/ships/transportation, d) military acronyms, or e) other. Step 2 – Ask probing questions and then locate useful and accurate information. Step 3 – Record and cite the sources correctly. “Learn by Doing” Step 1: Highlight by color-coding all important known and unknown terms; ID possible additional terms of interest. Comment [kwl1]: General questions for research based on terms in the transcript. Do not bother with Step 2: What questions should be asked? See review notes on the side of page for examples. items that are too generic or too broad (see examples below) Do this electronically with your own transcript. -

L!!Jiditj!Am¥Tiill I~~

l!!JIDItJ!am ¥tiill I ~ ~_ . ~ I . ~~~~~~~~J ~ ~ ~~' ~I ~ j~ 'ri ID ~h NORTH GERMAN LLOYD BREMEN * . * * * Twin Screw Mail Steamship George Washington C. POLACK Commander OFFICERS F. BLOCK , Chief Officer J. Hinsch, 2nd Officer H. Klare, 3rd Officer E. Soer, 2nd Officer G. Kirmss, 4th Officer E. tom Dieck, 2nd Officer H. Winterberg, 4th Officer Dr. STARKE, Physician Dr. KLO SE, Physician D. LAMPE, Chief Engineer E. Assmann, Ist Engineer I-I. AHLERS, P nrser T. SCHRODER , Commissary C. 'i\'ichmann, Commissary O. CAESAR, Chief Steward . C. Larson, 2nd Steward, 2nd Cabin L. Huck, 2nd Steward M. Oesterheld, 2nd Steward J. 'i\'estendorf, 2nd Steward K. Arnold, 2nd Steward J. Bottjer, 2nd Steward, 3rd Cabin M. ROLLE, Chief Cook H , HELMERS, Baggagemaster Wireless Telegraph Operators H . Schafer A. "Volf Traffic 'and Information Office C. SEGHORN, Manager SAILING FROM NEW YORK FOR BREMEN VIA PLYMOUTH AND CHERBOURG SATURDAY, APRIL 19, 1913 OELRICHS & CO., General Agente ,; BROADwAy (Bowling Green Offices) NEW YORK European Railw ay Tickets RA ILWAY TICKETS FROM BREMEN to the more important points in GERMANY, AUSTRIA, RUSSIA, SWEDEN, NORWAY, DENMARK, HOLLAND, BELGIUM and SWITZERLAND may ' be purchased on board the steamships • "/\ronprinzessin Cui/ie," "/\aiser Wilhelm / /," and "George Washington" from the Traffic Information Office; "Kaiser Wzlltebn der Grosse," from the Purser and on the" Kronprinz l¥z'lhe/m," and " Pn'nz Friedrich Wilhelm" from the Baggage Master. BAGGAGE CHECKED THROUGH TO DESTINATION The baggage of passengers provided with European railway tickets may be checked through to destination after the Custom's examination at Bremerhaven. Passengers holding European railway tickets beyond the German • frontier, are exempt from baggage examination at Bremerhaven. -

Military History Anniversaries 1201 Thru 121515

Military History Anniversaries 1 thru 15 December Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Dec 01 1918 – WWI: An American army of occupation enters Germany. Dec 01 1779 - American Revolution: General George Washington’s army settles into a second season at Morristown, New Jersey. Washington’s personal circumstances improved dramatically as he moved into the Ford Mansion and was able to conduct his military business in the style of a proper 18th-century gentleman. However, the worst winter of the 1700s coupled with the collapse of the colonial economy ensured misery for Washington’s underfed, poorly clothed and unpaid troops as they struggled for the next two months to construct their 1,000-plus “log-house city” from 600 acres of New Jersey woodland. Dec 01 1862 - Civil War: President Abraham Lincoln addresses the U.S. Congress and speaks some of his most memorable words as he discusses the Northern war effort. Lincoln used the address to present a moderate message concerning his policy towards slavery. Just10 weeks before, he had issued his Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that slaves in territories still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be free. The measure was not welcomed by everyone in the North–it met with considerable resistance from conservative Democrats who did not want to fight a war to free slaves. Dec 01 1919 – WWI: Three weeks after the armistice, and on the same day that Allied troops cross into Germany for the first time, a new state is proclaimed in Belgrade, Serbia. -

164 MINNESOTA HISTORY Anna Gilbertson and the Gold Star Mothers and Widows Pilgrimages After World War I

164 MINNESOTA HISTORY Anna Gilbertson and the Gold Star Mothers and Widows Pilgrimages after World War I Susan L. Schrader ar had been raging in Europe for almost three years brothers who had already immigrated. She married a Nor- Wwhen the United States entered the Great War, now wegian immigrant blacksmith, Otto Gilbertson. Together known as World War I, on April 6, 1917. Over the course they raised seven children, living first in Coon Valley, of the next 19 months, America sent two million men to Wisconsin, and later in Owatonna, Minnesota. Accord- war. Among the mothers and young wives who bid their ing to Anna’s granddaughter, Lois Schrader (the author’s soldiers farewell was Anna Gilbertson of Owatonna. Anna mother), Otto was a respected blacksmith, said to have sent two sons to fight— Arthur and Oscar. Oscar survived, been sought out to shoe the famous harness racer Dan but Arthur was stricken by disease aboard ship and died Patch. Otto’s life, however, was fraught with difficulty— October 10, 1918, upon reaching France.1 With the death of drinking, skirmishes with the law, and fits of rage. Anna’s one soldier- son, Anna became a Gold Star mother. marriage to Otto dissolved in the early 1930s. As a result, Years after the armistice on November 11, 1918, follow- Anna was destitute and moved to St. Cloud to live with ing much debate, the US government approved the Gold the family of one of her daughters, Myrtle Gilbertson Star mothers and widows pilgrimages of 1930–33— an all- Prokopec.3 expenses- paid program to take selected bereaved women Arthur Selmer Gilbertson was born to Anna and Otto to Europe to grieve at a son’s or husband’s grave. -

Ocean Liner Gala V

STEAmsHIP HisTOriCAL SOCieTY OF AmeriCA PresenTS OCEAN Liner GALA V VirTUAL AUCTION FUNDRAiser viA EvenT.Gives NOvember 7, 2020 PrevieW - 6:30PM ET Live SHOW - 7:00PM ET REMEMBERING United States Lines beneFITing THE SHIP HisTORY CENTER 2 Introduction Our theme for tonight’s Ocean Liner Gala V celebrates the heritage of the United States Lines. The following pages highlight USL’s visual chronology of iconic ships, along with colorful captions written by our president, Don Leavitt. The art design and layout was beautifully executed and donated by John Goschke. While we honor USL, we also are excited to share news of SSHSA’s future, during this our 85th Anniversary year. We have launched and are well underway in our first comprehensive campaign; Full Ahead! Steaming Into the Future, Reaching the Next Generation. It was designed to make SSHSA sustainable and relevant for the coming 100 years. As we approach our official 85th Anniversary date on November 10, 2020 – let’s pause a moment to blow off a little steam. The effort to sustainability began with the acquisition of our 8,000 square foot building. This key achievement has been accomplished. SSHSA now owns our building and it’s our first permanent home. There are so many to thank Full Ahead!TM who have helped us reach this important milestone. But this is just the beginning. Steaming Into the Future REACHING THE NEXT GENERATION As we embark together, funding the future, we plan to raise $3.5 million and set our course for new harbors, while still having the ability to persevere through storms. -

Summary Illicit Transactions and Seizures

C. 91. M. 91. 1946.XI. [O.C.S.SOO(z)] Geneva, December 1946. LEAGUE OF NATIONS ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON TRAFFIC IN OPIUM AND OTHER DANGEROUS DRUGS SUMMARY OF ILLICIT TRANSACTIONS AND SEIZURES DURING 1945 REPORTED TO THE SECRETARIAT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS Note The cost of printing this document, which was prepared by the Secretariat of the League of Nations, was borne by the United Nations. 4708. — 720 (F.). 650 (À.).l /47. Imp. Granchamp. Annemasse. — 3 — PART I CASES REPORTED IN PREVIOUS SUMMARIES IN REGARD TO WHICH FURTHER INFORMATION HAS BEEN RECEIVED Nil. PART II NEW CASES OF SEIZURES DIVIDED INTO THE FOLLOWING GROUPS : 1. R aw Opium . 4. H e r o in. 2. P repared Opiu m . 5. Cocaine. 3. Morph ine. 6. Ind ian H em p . 1. RAW OPIUM No. 2404. — Seizure at Alexandria on February 20th, 1945. Report communicated by the Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau, Cairo, May 24th, 1945. Reference : 1 (a). Opium : 5 kg. 239 gr. Origin unknown. O.C.S./Conf.l695. \ i r ^ 6 5 2. Wai Dang Fong, Young Ping Kong and Holi Tahou, Chinese seamen. 3. A Customs Police saw the three Chinese near the quay where the s.s. Klean Africa was berthed. As the Customs had received information that an attempt would be made to smuggle drugs from this steamer, they were followed and arrested and the opium in question was found on them. They stated that they had purchased it in Alexandria and meant to take it to Liverpool and resell it to fellow Chinese. -

SOMEWHERE at SEA Lookout ~Unrtuury the O God, Who Makelt Us Glad with the Yearly Remembrance December, 1944 No

1.00 U. S. Navy Plwto CHRISTMAS - SOMEWHERE AT SEA Lookout ~unrtuury The o God, who makelt us glad with the yearly remembrance December, 1944 No. 12 of the birth of thine only Son Jesus Christ; Grant that as We joyfu ll y receive him for our Redeemer, so we may with sure Con fidence behold him when He shall come to be our Judge, who [xhi6itio.JL .ot $Juwvm A.. OJ.oJdJtaiM.. liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, one God, world E,\l\IEN' - Choice - Jt1dges' without end . Am en. Choice of "best in sho\\" ." \Vill thevS agree? Thi was the big ques tion in ~he mind of a rt is ~ s .. ~e all1en and "isltor' at the Exll1b1tl on of rtraits of seamen by volunteer ~ists which was held in the Janet Roper Room from Octoher 24th to \"OJ. xxx\". DECDIllER. 1944 oVl'lllber 8th. PUBLISHED MONTHLY Thomas Craven, art critic, Gor by the don Grant. fam ous marine artist and SEAMEN'S CHURCH . I. Woolf, )Jew York Til11 e~ INSTITUTE OF NEW YORK artist. graciously consented to serve a judges. A luncheon was given CLARENCE G. MICHALIS Prc.idcnt n October 24th, attended by the THOMAS ROBERTS Secretary and Treasurer volunteer artists and at which the REV . HAROLD H. KELLEY. D .O . judges announced their deci sion. Director The\' selected a portrait 0 f Seaman MARJORIE DENT CANDEE. Editor Boh' Crosby a first prize \\'inner. $1.00 per year lOe per copy made by Thlrs. H elen H. Lawrence Gifts of $5.00 per year and over include a year's subscription to "mE who recently completed her 100th SEAMAN BOB CROSBY, Age 18, LOOKOUT'. -

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT Papers As Assistant Secretary of the Navy

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT • ____~e' Papers as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1913 - 1920 Accession Nos. 42-150, 43-90, 43-169, 43-170, 47-15, 48-21 The Papers as Assistant Secretary of the Navy were donated to the Library by Franklin D. Roosevelt and by his estate. The literary property rights in them have been donated to the United States Government. Quantity: 36 linear feet (approximately 72,000 pages) Restrictions: None Related Materials: i1aterial relating to Franklin D. Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary of the Navy will be found in the Fred Colvin Papers (entire collection); the Louis Howe Papers - Navy Papers, 1913-1921; Franklin D. Roosevelt Family, Business and Personal Papers, Naval Affairs - Newport Investigation, 1921, the Rathom Case - Correspondence 1920-1921, the Rathom Case - Exhibits, etc. 1920-1921, and Naval Matters 1920-1922. Copies of materials found in the National Archives Record Group 80 (Offices of the Secretary of the Navy) are filed under "Copies of Materials from Other Repositories." To see this material consult the archivist on duty. Franklin D. Roosevelt was Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, 1913-1921. His papers include material relating to the administration of the United States Navy, Federal patronage and Democratic party affairs in New York State, Roosevelt's campaign for United States Senator from New York in 1914, the campaign to re-elect Woodrow Wilson in 1916, and the movement to nominate Roosevelt as the Democratic candidate for Governor of New York in 1918. The papers are arranged in two series as follows: I. -

![1922-01-15 [P 12]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9431/1922-01-15-p-12-7259431.webp)

1922-01-15 [P 12]

~~"~ will cover all the south of - territory brief, however. In addition to notify¬ minated In the rhnrze th., American Sets Forty-second Street. The other, with Return of Striker« ing the union that the shops' reopen- last summe,- Morin fjJïïf* .>}. nirt, LawyerFlogged, Scrapped Battleship Enright headquarter« at 229 West 123d Street ing is to be accompanied by a restora- in Walter's well. *Ç0 h¡rP*n» «^ii will be Traffic Precinct B, and Will tion of eonditions ealled for the as To Garment by Walter tested r Then Driven To Sink With Honors of cover the rest of Manhattan. Shops old agreement, including week-work morning. thí^VAe»ny r-e,. War Record in Commissioner Enright previously and the old wage« and hours, the letter .The -».eg, startled Big had abolished seven police stations, This Week is said to decline that the manufactur¬ He, Sir ArtB. new Expected principal of the C«r- some of them ones, making the ers in such action "do not. waive bbtained unlÄ?*y' From boundaries before taking bail, suspended W *'. Louisiana Plans to already far-oxtendcd their to from the sors and Navy Fitting Ceremonial Mark of Police Shift did right appeal injunc¬ prevented p,bi Passing he made his new plan nubile. He in Plant» tion, or to waive any other rights they given the case t'.pr,of«'-s .*W Gallant Sea as nway with the Greenwich Street strt- Delay Reopening have in the matter." to pending Il Fighters Result of Dis¬ from onM modification of (Continu«*) ntqo tion, the Sheriff Street station, the lInderCourt's Order Occa¬ comment, on a Nowpoking A!6*1« Chicago Counsel for Two Al¬ Asked for statement Professor Morin has . -

Ship Sales and Transfers

Annual Report of the FEDERAL MARITIME BOARD MARITIME ADMINISTRATION 1951 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE I , CHARLES SAWYER, Secretary /-i ' ,) ' t Washington, D. C. I U-r) '3 l ,. [jl ''"~ • I FEDERAL MARITIME BOARD EDwARD L. CocHRANE, Chairman RoBERT W. WILLIAMS, Vice Chairman ALBERT w. GATOV A. J. WILLIAMs, Secretary MARITIME ADMINISTRATION EDwARD L. CocHRANE, 111.aritime Administrator EARL W. CLARK, Deputy Maritime Administrator For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. • Price 35 cents (paper cover) ...:lt-~~ 2409' Letters of Transmittal UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, MARITIME ADMINISTRATION, Washington 25, D. C., January 1, 1952. To: The Secretary of Commerce. FRoM: Chairman, Federal Maritime Board, and Administrator; Mari time Administration. SuBJECT: Annual Report for fiscal year 1951. I am submitting herewith the report of the Federal Maritime Board and Maritime Administration for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1951. This report covers the first full year of operation of these two agencies. It has been a year which once more has demonstrated the importance of the merchant marine to the national economy and defense. E. L. CocHRANE, ' Chairman, Federal Maritime Board, and Maritime Administrator. THE SECRETARY oF CoMMERCE, Washington 25, D. C. To the Congress: I have the honor to present the annual report of the Federal Mari time Board and Maritime Administration of the United States Depart ment of Commerce for the fiscal