From Pazardzhik to Prague: Ginka Varbakova and the Multilevel Clientelism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Company Profile

www.ecobulpack.com COMPANY PROFILE KEEP BULGARIA CLEAN FOR THE CHILDREN! PHILIPPE ROMBAUT Chairman of the Board of Directors of ECOBULPACK Executive Director of AGROPOLYCHIM JSC-Devnia e, ECOBULPACK are dedicated to keeping clean the environment of the country we live Wand raise our children in. This is why we rely on good partnerships with the State and Municipal Authorities, as well as the responsible business managers who have supported our efforts from the very beginning of our activity. Because all together we believe in the cause: “Keep Bulgaria clean for the children!” VIDIO VIDEV Executive Director of ECOBULPACK Executive Director of NIVA JSC-Kostinbrod,VIDONA JSC-Yambol t ECOBULPACK we guarantee the balance of interests between the companies releasing A packed goods on the market, on one hand, and the companies collecting and recycling waste, on the other. Thus we manage waste throughout its course - from generation to recycling. The funds ECOBULPACK accumulates are invested in the establishment of sustainable municipal separate waste collection systems following established European models with proven efficiency. DIMITAR ZOROV Executive Director of ECOBULPACK Owner of “PARSHEVITSA” Dairy Products ince the establishment of the company we have relied on the principles of democracy as Swell as on an open and fair strategy. We welcome new shareholders. We offer the business an alternative in fulfilling its obligations to utilize packaged waste, while meeting national legislative requirements. We achieve shared responsibilities and reduce companies’ product- packaging fees. MILEN DIMITROV Procurator of ECOBULPACK s a result of our joint efforts and the professionalism of our work, we managed to turn AECOBULPACK JSC into the largest organization utilizing packaging waste, which so far have gained the confidence of more than 3 500 companies operating in the country. -

Regional Case Study of Pazardzhik Province, Bulgaria

Regional Case Study of Pazardzhik Province, Bulgaria ESPON Seminar "Territorial Cohesion Post 2020: Integrated Territorial Development for Better Policies“ Sofia, Bulgaria, 30th of May 2018 General description of the Region - Located in the South-central part of Bulgaria - Total area of the region: 4,458 km2. - About 56% of the total area is covered by forests; 36% - agricultural lands - Population: 263,630 people - In terms of population: Pazardzhik municipality is the largest one with 110,320 citizens General description of the Region - 12 municipalities – until 2015 they were 11, but as of the 1st of Jan 2015 – a new municipality was established Total Male Female Pazardzhik Province 263630 129319 134311 Batak 5616 2791 2825 Belovo 8187 3997 4190 Bratsigovo 9037 4462 4575 Velingrad 34511 16630 17881 Lesichovo 5456 2698 2758 Pazardzhik 110302 54027 56275 Panagyurishte 23455 11566 11889 Peshtera 18338 8954 9384 Rakitovo 14706 7283 7423 Septemvri 24511 12231 12280 Strelcha 4691 2260 2431 Sarnitsa 4820 2420 2400 General description of the Region Population: negative trends 320000 310000 300000 290000 280000 Pazardzhik Province 270000 Population 260000 250000 240000 230000 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 There is a steady trend of reducing the population of the region in past 15 years. It has dropped down by 16% in last 15 years, with an average for the country – 12.2%. The main reason for that negative trend is the migration of young and medium aged people to West Europe, the U.S. and Sofia (capital and the largest city in Bulgaria). -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

COMMUNICORP GROUP Presents BG RADIO Is the Home of the Contemporary Bulgarian Pop and Rock Music

COMMUNICORP GROUP presents BG RADIO is the home of the contemporary Bulgarian pop and rock music. It has been the first radio station that airs exclusively Bulgarian music only, in more than 21 cities in Bulgaria. BG RADIO is among the stations with largest broadcast coverage in the country and is one of the favorite ones as well. The music selection consists of the Golden Bulgarian Hits and the newest current hits. BG RADIO has been dedicated to its mission to positively affirm and support the Bulgarian traditions, values and development. BG RADIO launched with the goal to present the contemporary Bulgarian pop and rock music with a chance for appearance. This mission carried away hundreds of thousands of listeners and at the tenth year of its existence BG RADIO is the most popular radio station in Bulgaria of people aged between 36 and 45 years and in the top 5 positions in the preferences of the audience over 25 years. The media annually organizes a grand ceremony at the Annual Musical Awards of BG RADIO, the only awards, voted entirely by the listeners. BG RADIO airs in: Sofia, Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, Veliko Turnovo. Blagoevgrad, Pleven, Pazardzhik, Shumen, Ihtinam, Ahotpol, Botevgrad, Gabrovo, Lovech, Malko Turnovo, Yablanica, Yambol, Goce Delchev, Shabla and on all artery highways in the country. 2 3 RADIO 1 is the leading radio station in Bulgaria. The radio format is Soft Adult Contemporary, covering the most popular and melodious songs from the 60s onwards - or the so called – “classic hits”. However, RADIO 1 is not a radio station for "oldfashioned" music - many contemporary hits find their place in the program. -

Bulgaria Service Centers / Updated 11/03/2015

Bulgaria Service Centers / Updated 11/03/2015 Country Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D DASP name Progress Progress Progress Progress Center Center Center Center Sofia 1574 69a Varna 9000 Varna 9000 Burgas 8000 Shipchenski Slivntisa Blvd Kaymakchala Konstantin Address (incl. post code) and Company Name prohod blvd. 147 bl 19A n Str. 10A. Velichkov 34, CAD R&D appt. Flysystem 1 fl. Kontrax Progress Vizicomp Center Country Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria City Sofia Varna Varna Burgas General phone number 02 870 4159 052 600 380 052 307 105 056 813 516 Business Business Business Business Opening days/hours hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– 17:30 17:30 17:30 17:30 Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Ruse 7000 Shumen Stara Zagora Plovdiv 4000 Burgas 8000 Pleven 5800 Sliven 8800 Pernik 2300 Burgas 8000 Tsarkovna 9700 Simeon 6000 Ruski Bogomil Blvd Demokratsiy San Stefano Dame Gruev Krakra Str Samouil 12A. Nezavisimost Veliki Str 5. Blvd 51. 91. Pic a Blvd 67. Str 30. Str 30. Best 68. Krakra Infostar Str 27. SAT Com Viking Computer Pic Burgas Infonet Fix Soft Dartek Group Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Burgas Stara Zagora Plovdiv Burgas Pleven Ruse Sliven Pernik Shumen 056 803 065 042 -

Republic of Bulgaria Ministry of Energy 1/73 Fifth

REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA MINISTRY OF ENERGY FIFTH NATIONAL REPORT ON BULGARIA’S PROGRESS IN THE PROMOTION AND USE OF ENERGY FROM RENEWABLE SOURCES Drafted in accordance with Article 22(1) of Directive 2009/28/EC on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources on the basis of the model for Member State progress reports set out in Directive 2009/28/EC December 2019 1/73 REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA MINISTRY OF ENERGY TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS USED ..................................................................................................................................4 UNITS OF MEASUREMENT ............................................................................................................................5 1. Shares (sectoral and overall) and actual consumption of energy from renewable sources in the last 2 years (2017 and 2018) (Article 22(1) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ........................................................................6 2. Measures taken in the last 2 years (2017 and 2018) and/or planned at national level to promote the growth of energy from renewable sources, taking into account the indicative trajectory for achieving the national RES targets as outlined in your National Renewable Energy Action Plan. (Article 22(1)(a) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 2.a Please describe the support schemes and other measures currently in place that are applied to promote energy from renewable sources and report on any developments in the measures used with respect to those set out in your National Renewable Energy Action Plan (Article 22(1)(b) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ..................... 18 2.b Please describe the measures in ensuring the transmission and distribution of electricity produced from renewable energy sources and in improving the regulatory framework for bearing and sharing of costs related to grid connections and grid reinforcements (for accepting greater loads). -

Notices from Member States

C 248/4EN Official Journal of the European Union 30.9.2008 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES First processing undertakings in the raw tobacco sector approved by the Member States (2008/C 248/05) This list is published under Article 171co of Commission Regulation (EC) No 1973/2004 of 29 October 2004 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 1782/2003 as regards the tobacco aid scheme. BELGIUM „Topolovgrad — BT“ AD Street „Hristo Botev“ 10 MANIL V. BG-8760 Topolovgrad Rue du Tambour 2 B-6838 Corbion „Bulgartabak Holding“ AD TABACS COUVERT Street „Graf Ignatiev“ 62 Rue des Abattis 49 BG-1000 Sofia B-6838 Corbion „Pleven — BT“ AD TABAC MARTIN Sq. „Republika“ 1 Rue de France 176 BG-5800 Pleven B-5550 Bohan BELFEPAC nv „Plovdiv — BT“ AD R.Klingstraat, 110 Street „Avksentiy Veleshki“ 23 B-8940 Wervik BG-4000 Plovdiv VEYS TABAK nv „Gotse Delchev — Tabak“ AD Repetstraat, 110 Street „Tsaritsa Yoana“ 12 B-8940 Wervik BG-2900 Gotse Delchev MASQUELIN J. „ — “ Wahistraat, 146 Dulovo BT AD „ “ B-8930 Menen Zona Sever No 1 BG-7650 Dulovo VANDERCRUYSSEN P. Kaaistraat, 6 „Dupnitsa — Tabak“ AD B-9800 Deinze Street „Yahinsko Shose“ 1 BG-2600 Dupnitsa NOLLET bvba Lagestraat, 9 „Kardzhali — Tabak“ AD B-8610 Wevelgem Street „Republikanska“ 1 BG-6600 Kardzhali BULGARIA „ — “ (BT = Bulgarian tobacco; AD = joint stock company; Pazardzhik BT AD „ “ VK = universal cooperative; ZPK = Insurance and Reinsurance Street Dr. Nikola Lambrev 24 Company; EOOD = single-person limited liability company; BG-4400 Pazardzhik ET = sole trader; OOD = limited liability company) „Parvomay — BT“ AD „Asenovgrad — Tabak“ AD Street „Omurtag“ 1 Street „Aleksandar Stamboliyski“ 22 BG-4270 Parvomay BG-4230 Asenovgrad „ “ „Sandanski — BT“ AD Blagoevgrad BT AD „ “ Street Pokrovnishko Shosse 1 Street Svoboda 38 BG-2700 Blagoevgrad BG-2800 Sandanski „Missirian Bulgaria“ AD „Smolyan Tabak“ AD Blvd. -

INVASION of BEE SAMPLES with VARROA DESTRUCTOR Delka

TRADITION AND MODERNITY IN VETERINARY MEDICINE, 2018, vol. 3, No 1(4): 25–29 INVASION OF BEE SAMPLES WITH VARROA DESTRUCTOR Delka Salkova1, Kalinka Gurgulova2, Ilian Georgiev3 1Institute of Experimental Morphology, Pathology and Anthropology with Museum, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria 2National Diagnostic & Research Veterinary Medical Institute „Prof. Dr G. Pavlov“,Sofia, Bulgaria 3University of Forestry, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Sofia, Bulgaria E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this work was to estimate the level of infestation of bee samples infested with Varroa de- structor. It has been performed a laboratory assay of bee samples for the presence of the mite Varroa destructor. The investigation was for a period of two years – 2015 and 2016. The bee samples were collected from diseased and dead bee colonies owned by 149 beekeepers. The result showеd that from 220 bee samples tested, 36% were positive for Varroa mite and negative samples were 64%. The level of infestation in positive samples was as follows: less than 5% were in 39.2% of samples, between 5 to 20% and more than 20% were found in 30.4% for each level, respectively. In conclusion more than a third of the bee samples were infested with Varroa mites. Most of the bee samples had a low degree of invasion (< 5%) and the average and the high level of invasion of bee samples were represented by the same values. Key words: Apis mellifera, bee sample, Varroa destructor, laboratory assay. Introduction Varroa destructor mite (Anderson & Trueman, 2000) is an ectoparasite that poses a serious threat to the honeybee Apis mellifera L. -

Gypsies / Roma in Bulgaria Professing Islam - Ethnic Identity (Retrospections and Projections)

International Relations GYPSIES / ROMA IN BULGARIA PROFESSING ISLAM - ETHNIC IDENTITY (RETROSPECTIONS AND PROJECTIONS) Georgi KRASTEV1 Evgeniya I. IVANOVA2 Velcho KRASTEV3 ABSTRACT: GYPSIES/ROMA IN BULGARIA WHO PROFESS ISLAM HAVE HETEROGENEOUS ETHNIC AND GROUP IDENTITY. IN THE YEARS AFTER SEPTEMBER 1944 TO 1990 (THE TIME OF THE SO-CALLED SOCIALISM IN BULGARIA) AMONG MANY OF THEM THERE IS A STRIVING FOR SELF-DETERMINATION WITH A TURKISH IDENTITY, AT THE SAME TIME THE STATE POLICY IS TO PRESERVE THEIR GYPSY IDENTITY, AND SUBSEQUENTLY-TO ASSIMILATION. DEMOCRATIC CHANGES IN BULGARIAN SOCIETY AFTER 1990 LEAD TO THE OPENING OF BORDERS AND FREE MOVEMENT, ACCESSION TO THE EUROPEAN UNION. IN THIS CONTEXT, A PART OF THE UNEMPLOYED ROMA (GYPSY) COMMUNITY MIGRATES IN SEARCH OF WORK FROM VILLAGES AND TOWNS TO THE CAPITAL AND SOME OF THE MAJOR CITIES IN THE COUNTRY, OTHERS EMIGRATE AND SETTLE IN DIFFERENT EUROPEAN COUNTRIES, THIRD AND MARGINALIZED IN THEIR TRADITIONAL HABITATS. DURING THE LAST TEN YEARS, THERE HAVE BEEN PROCESSES OF REISLAMISATION OR ISLAMIZATION IN THE ROMA, WHO PROFESS ISLAM. REISLAMIZATION IS PRESENTED AS A RETURN TO TRADITION, BUT IN FACT IT IS A VISIBILITY OF THE PROCESS. THE COMBINATION OF LACK OF EDUCATION, NON-INTEGRATION INTO SOCIETY, SOCIAL EXCLUSION, MARGINALIZATION, ACCOMPANIED BY ATTEMPTS TO PERSISTENTLY IMPOSE CONSERVATIVE RELIGIOUS UNDERSTANDINGS AND PRACTICES, CREATES PREREQUISITES FOR RADICALIZATION IN INDIVIDUAL POPULATED SOME GROUPS. KEY WORDS: MUSLIM ROMA, ISLAM, ETHNIC IDENTITY, RE-ISLAMIZATION. INTRODUCTION Gypsies/ Roma have been living in Bulgarian lands for centuries along with other ethnic groups. Many Gypsy groups with their own ethno- and sociocultural characteristics, differing 1 Georgi Krastev, PhD, Assistant, Academy of Ministri of Interior of Sofia, Bulgaria, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Evgeniya I. -

Cause of Action a Series by the European Roma Rights Centre

CAUSE OF ACTION A SERIES BY THE EUROPEAN ROMA RIGHTS CENTRE Reproductive Rights of Romani Women in Bulgaria APRIL 2020 CHALLENGING DISCRIMINATION PROMOTING EQUALITY Copyright: ©European Roma Rights Centre, April 2020 Please see www.errc.org/permissions for more information about using, sharing, and citing this and other ERRC materials Design: Anikó Székffy Layout: Dzavit Berisha Cover photo: © ERRC This report is published in English Address: Avenue de Cortenbergh 71, 4th floor, 1000 Brussels, Belgium E-mail: [email protected] www.errc.org SUPPORT THE ERRC The European Roma Rights Centre is dependent upon the generosity of individual donors for its continued existence. Please join in enabling its future with a contribution. Gifts of all sizes are welcome and can be made via PAYPAL on the ERRC website (www.errc.org, click on the Donate button at the top right of the home page) or bank transfer to the ERRC account: Bank account holder: EUROPEAN ROMA RIGHTS CENTRE Bank name: KBC BRUSSELS IBAN: BE70 7360 5272 5325 SWIFT code: KREDBEBB CAUSE OF ACTION: REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS OF ROMANI WOMEN IN HUNGARY Table of Contents Introduction 3 The Situation of the Roma in Bulgaria 5 Demographics and health status 5 Social disadvantages 5 Social exclusion 6 The Legal Framework in Bulgaria 7 Anti-discrimination 7 Healthcare 7 Roma in the Bulgarian Healthcare System 8 Fact Finding 11 Interviews: Method and Sample 11 The Findings 12 Segregated wards 12 Inferior material conditions 13 Inferior hygienic conditions 14 Limited contact with visitors 14 Lack of accessible information 14 Neglect by the medical staff 15 Breaching of confidentiality and humiliation 15 Verbal insults 16 Obstetric violence 17 Corruption 18 Individual perception of different treatment 19 Phone Call-Based Testing 19 A Complaint Against Bulgaria Before the European Committee of Social Rights 21 An Antecedent Complaint from 2007 21 The Complaint No. -

2018 Annual Report of the Ombudsman Acting As National Preventive Mechanism

2018 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE OMBUDSMAN ACTING AS NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISM CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS 3 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISM IN 2017 4 Legal Framework 4 1. The Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT) 4 2. Ombudsman Act 4 3. Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria 5 4. Administrative Procedure Code 6 5. Judicial System Act 6 DETENTION FACILITIES 7 1. Use of firearms and instruments of restraint 8 2. Unresolved problem with overcrowdedness, failing mechanism under Article 46(2) EPRCA and no statutory standards as regards daylight 10 3. Infringement of the rights of defence of the persons deprived of their liberty by field operatives of the Ministry of Interior in prisons 12 4. Some constitutional rights related to serving the punishment deprivation of liberty 16 5. Health services in places of detention 29 PROTECTION OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS 34 1. Places for temporary accommodation of foreigners with the Ministry of Interior 34 2. Closed-type facilities with the State Agency for Refugees – Busmantsi, Sofia; Pastrogor; and Harmanli 36 PROTECTION OF PEOPLE WITH MENTAL ILLNESSES 38 1. Funding and human resources 38 2. Location and facilities 39 3. Healthcare. Protection and security for patients 39 4. Continuity of care and deinstitutionalization of psychiatric help 41 5. Information campaigns 42 SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS FOR CHILDREN AND ADULTS 43 1. Social institutions for children 43 2. Social institutions for adults 45 2 ABBREVIATIONS SAA – Social Assistance Agency DGEP – Directorate General -

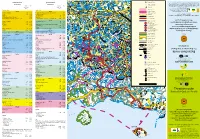

THRACIAN ROUTE Byzantium Route Be Cannot It Circumstances No at and Smolyan of Municipality the from Carried Is Map the of Content The

Regional Center Member”. Negotiated the and Union European the of position official the reflect map this that consider THRACIAN ROUTE Byzantium Route be cannot it circumstances no at and Smolyan of Municipality the from carried is map the of content the by the European Union through the European Fund for Regional Development. The whole responsibility for for responsibility whole The Development. Regional for Fund European the through Union European the by Hour Distribution Hour Distribution co-funded 2007-2013, Greece-Bulgaria cooperation territorial European for Programme the of aid financial Municipal Center the with implementing is which THRABYZHE, ACRONYM: Coast”. Sea Aegean Northern the and Mountains Distance Time Distance Time Rhodopi the in Heritage Cultural Byzantine and “Thracian 7949 project the within created is map “This (with accumu- (with accumu- City Hall Shishkov” “Stoyu tory - lation) lation)Septemvri his of museum Regional - partner Bulgarian Belovo State border Municipality Samothrace - partner Greece Arrival in Chepelare Arrival in Devin Pazardzhik Municipality Smolyan - partner Lead Day One Day One Regional border Chirpan Municipal border Departure from Chepelare 0 km 00:00 h The Byzantium and Bulgarian fortress “Devinsko Gradishte” 05:00 h 2013» - 2007 Bulgaria - Greece Zabardo 27 km 00:32 h The Natural Landmark “Canyon” 02:00 h Plovdiv Highway Cooperation Territorial European for «Programme the for Funding Ancient road 02:00 h Departure from Devin 0 km 00:00 h Project road Natural landmark “The Wonderful Bridges”