Heartbreak Hotel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

ELVIS Blue Suede Shoes Activity

JANUARY 1956 30 Elvis Presley recorded his version of “Blue Suede Shoes.” • The song was written by Carl Perkins. He was hospitalised after crashing his car on his way to promote the song on a TV show. Elvis recorded the song instead. • Elvis had 51 gold records and 149 hit singles between 1958 and 1986. of the day • Other performers to record the song include the Beatles, John Lennon, Jimi Hendrix. suede Leather with a napped (soft- ly brushed) surface; from the French gants de Suéde (Swedish gloves). Elvis Presley: They arrived today. The shoes. The ones you bid Recording cover versions of songs was a common practice for on that Internet auction site. They were during the 1940s and 1950s, and "Blue Suede Shoes" was claimed to be Elvis Presley’s original blue suede shoes. Of course, who’d believe that? Still, for one of the first songs RCA Victor wanted its newly $10, they’re pretty cool. Go on, put them on. contracted artist, Elvis Presley, to record. "Heartbreak Hotel" Hmm, nice fit. Although, . all of a sudden you and "Shoes" rose on the chartsof atthe roughly day the same time. feel like, well, as though you want to . “Good mashed potato is one of the great luxu- ries of life and I don’t blame Elvis for eating it every night for the last year of his life.” Lyndsey Bareham Elvis song word search Find all the hidden Elvis songs. The letters left of the day over spell out another great Elvis hit! HOUNDDOGAR EYOUN Blue Moon BLUESUEDESHOESO Blue Suede Shoes LREDNETEMEVOLONO Don’t Be Cruel DONT B E C RUE L YAWYM Heartbreak Hotel Hound Dog SUSP I C IOUSMINDSE In the Ghetto EOTTEHGEHTN I SOMU Jailhouse Rock PROMI SEDLANDETOL Kentucky Rain LETOHKAERBTRAEHB Love Me Tender NIGNIARYKCUTNEK My Way JAI LHOUSEROCKHT Promised Land Are You Lonesome Tonight? Lonesome You Are Suspicious Minds Answer: . -

C E7 Verse: All of Me Why Not Take All of Me, A7 Dm Can't You See I'm No

All of Me by Frank Sinatra C E7 Verse: All of me why not take all of me, A7 Dm Can’t you see I’m no good without you? E7 Am Take my lips, I want to lose them D7 Dm G7 Take my arms I’ll never use them. C E7 Chorus: Your goodbye left me with eyes that cry A7 Dm How can I get along without you. F Fm Em7 A7 You took the part that once was my heart D7 G7 C So why not, why not take all of me? C E7 Verse: All of me come on get all of me A7 Dm Can’t you see I’m just a mess without you? E7 Am Take my lips, I want to lose them D7 Dm G7 Get a piece of these arms, I’ll never use them C E7 Chorus: Your goodbye left me with eyes that cry A7 Dm How can I ever make it without you F Fm You know you got the part Em7 A7 That used to be my heart D7 G7 C So why not, why not take all of me January 31st, 2020 1 It Had to Be You by Frank Sinatra Cmaj7 A7 It had to be you, it had to be you D7 I wandered a-round and finally found somebody who G7 Am Could make me be true___. Could make me feel blue D7 G7 And even be glad, just to be sad, thinking of you. C A7 Some others I’ve seen might never be mean D7 Might never be cross or try to be boss, but they wouldn’t do Dm Fm C E7 Am For nobody else gave me a thrill, with all your faults I love you still Gdim G7 Gdim G7 C It had to be you, wonderful you, it had to be you. -

Kidd Galahad Elvis Tribute Artist Set List Kidd Galahad Is an Elvis

Kidd Galahad Elvis Tribute Artist Set List Kidd Galahad is an Elvis Tribute Artist with a vast set list, covering all eras of Elvis' music. Listed here is a small list we have compiled of the songs he performs. Please feel to choose your own set list for your event. All Shook Up Guitar Man (Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear Always On My Mind Heartbreak Hotel Little Less Conversation An American Trilogy Heart Of Rome Little Sister And The Grass Won't Pay No Mind Hey Jude Life Are You Lonesome Tonight Hound Dog Love Letters Big Boots Hurt Love Me Big Boss Man If I Get Home On Christmas Day Love Me Tender Big Hunk O' Love I Can't Stop Loving You Mama Liked The Roses Blue Christmas I Got A Woman (Marie's The Name) His Latest Flame Bossa Nova Baby I Just Can't Help Believin' Mary In The Morning Bridge Over Troubled Water I Want You, I Need You, I Love You Maybellene Burning Love I'll Remember You Memories Can't Help Falling In Love Impossible Dream Moody Blue Don't I'm Leavin' Mr Songman Don't Be Cruel I'm So Lonely I Could Cry My Babe Don't Cry Daddy In The Ghetto My Baby Left Me Fever It's Impossible My Boy Fool It's Now Or Never My Way For The Good Times It's Easy For You Mystery Train For The Heart I've Lost You Next Step Is Love For Ol' Times Sake It's Your Baby, You Rock It! (Now & Then There's) A Fool Such As I GI Blues Jailhouse Rock Old MacDonald Girl Of My Best Friend Johnny B. -

WDAM Radio's History of Elvis Presley

Listeners Guide To WDAM Radio’s History of Elvis Presley This is the most comprehensive collection ever assembled of Elvis Presley’s “charted” hit singles, including the original versions of songs he covered, as well as other artists’ hit covers of songs first recorded by Elvis plus songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis! More than a decade in the making and an ongoing work-in-progress for the coming decades, this collection includes many WDAM Radio exclusives – songs you likely will not find anywhere else on this planet. Some of these, such as the original version of Muss I Denn (later recorded by Elvis as Wooden Heart) and Liebestraum No. 3 later recorded by Elvis as Today, Tomorrow And Forever) were provided by academicians, scholars, and collectors from cylinders or 78s known to be the only copies in the world. Once they heard about this WDAM Radio project, they graciously donated dubs for this archive – with the caveat that they would never be duplicated for commercial use and restricted only to musicologists and scholarly purposes. This collection is divided into four parts: (1) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S singles hits in chronological order – (2) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S and U K singles, the original versions of these songs by other artists, and hit versions by other artists of songs that Elvis Presley recorded first or had a cover hit – in chronological order, along with relevant parody/answer tunes – (3) Songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley – mostly, but not all in chronological order – and (4) X-rated or “adult-themed” songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley. -

Pastel Classics Repertoire

Pastel Classics Repertoire Always on my mind. Willie Nelson A song for you. Don Hathaway At last. Etta James Bennie and the jets. Elton John Bridge over troubled water. Simon and Garfunkel Can’t help falling in love. Elvis Presley Cryin. Roy Orbison Don’t let the sun go down on me. Elton John Georgia on my mind. Ray Charles Hallelujah. Leonard Cohen Have I told you lately. Rod Stewart Heartbreak hotel. Elvis Presley Heart of the matter. Don Henley Heaven. Bryan Adams Hopelessly devoted. Grease Hotel California. Eagles I can’t make you love me. Bonnie Raitt I walk the line. Johnny Cash I’ll stand by you. The Pretenders Just give me one reason. Traci Chapman Let’s get it on. Marvin Gaye Love me tender. Elvis Presley Pastel Classics Repertoire continued Moon river. Glenn Miller My way. Frank Sinatra Natural woman. Aretha Franklin Oh darling. Beatles Piano man. Billy Joel See you again. Wiz Khalifah Smile. Frank Sinatra Somewhere over the rainbow. Judy Garland Sorry seems to be the hardest word. Elton John Stand by me. Otis Redding Stop in the name of love. The Supremes Take me to church. Hosier Thinking out loud. Ed Sheeran Time after time. Cyndi Lauper True colours. Cyndi Lauper Unchained melody. Everly Brothers Unforgettable. Nat King Cole We’ve got tonight. K.Rogers+Dolly Parton What a wonderful world. Louis Armstrong When a man loves a woman. Percy Sledge Wild horses. Rolling Stones Your song. Elton John You’re the want that I want. Grease . -

Title Artist 3 Preludes__Piano Gershwin After the Gold Rush Neil

Title Artist 3_Preludes__piano_ Gershwin After The Gold Rush Neil Young Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't Too Proud to Beg Temptations All of me John Legend Jazz Standard / Frank All Of Me Sinatra Jazz Standard / Frank All The Things You Are Sinatra Angel Of Harlem U2 Angry Young Man Billy Joel Any major dude Steely Dan Apologize One Republic April Showers Artist Name At Last Jazz Standard Autumn Leaves Kosma-mercer Baby i love your way Peter Frampton Bad bad leroy brown Jim Croce Creedence Clearwater Bad moon rising Revival Bein Green Bennie And The Jets Elton John Billie Jean Michael Jackson Birthday Beatles Black Magic Woman Santana Brick House The Commodores Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon And Garfunkle Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Cake By The Ocean Dnce Calling All Angels Train Can’t Stop The Feeling JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE Carry on my wayward son Kansas Cats In The Cradle Cecilia Paul Simon Change The World Eric Clapton Clocks Coldplay Come Fly With Me Frank Sinatra Come Together Beatles Couldn't Stand The Weather Stevie Ray Vaughn Crazy Gnarls Barkley Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Dear prudence Beatles December, 1963 (Oh What A Night) Frankie Vallie Demons Imagine Dragons Desperado Eagles Dirtywork Steely Dan DOCK OF THE BAY Otis Redding Dont Ask Me Why Billy Joel Dont let the sun go down on me Elton John Don't Stop Fleetwood Mac Dont Stop Believin Journey Dont Stop Till You Get Enough Michael Jackson Down Under Men At Work Drive My Car Beatles Drops Of Jupiter Train Dynomite Every Little -

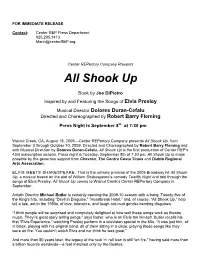

All Shook Up

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Center REP Press Department 925.295.1413 [email protected] Center REPertory Company Presents All Shook Up Book by Joe DiPietro Inspired by and Featuring the Songs of Elvis Presley Musical Director Dolores Duran-Cefalu Directed and Choreographed by Robert Barry Fleming Press Night is September 8th at 7:30 pm Walnut Creek, CA, August 18, 2009––Center REPertory Company presents All Shook Up, from September 3 through October 10, 2009. Directed and Choreographed by Robert Barry Fleming and with Musical Direction by Dolores Duran-Cefalu, All Shook Up is the first production of Center REP’s 43rd subscription season. Press night is Tuesday, September 8th at 7:30 pm. All Shook Up is made possible by the generous support from Chevron, The Contra Costa Times and Diablo Regional Arts Association. ELVIS MEETS SHAKESPEARE. That is the unlikely premise of the 2005 Broadway hit All Shook Up, a musical based on the plot of William Shakespeare’s comedy Twelfth Night and told through the songs of Elvis Presley. All Shook Up comes to Walnut Creek’s Center REPertory Company in September. Artistic Director Michael Butler is certainly opening the 2009-10 season with a bang. Twenty-five of the King’s hits, including “Devil in Disguise,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” and, of course, “All Shook Up,” help tell a tale, set in the 1950s, of love, tolerance, and laugh-out-loud gender-bending disguises. “I think people will be surprised and completely delighted at how well these songs work as theatre music. They’re great story-telling songs,” says Butler, who is an Elvis fan himself. -

The King of Rock 'N' Roll

1 Leggi e ascolta il brano. Elvis Presley: The King of rock ‘n’ roll Elvis Presley was the first rock ‘n’ roll superstar. His nickname was ‘The King’ because he was the king of rock ‘n’ roll. He was born on 8th January, 1935 in the state of Mississippi. His parents were poor and he was an only child. When he was a teenager his passion was music: gospel, blues and country. His favourite singers were the country singer Hank Snow, Mario Lanza and Dean Martin. He was a great singer and a sensational dancer. He had black hair and blue eyes and he was very good-looking. Elvis’s first hits were ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, ‘Jailhouse Rock’ and ‘Blue Suede Shoes’. These songs are now rock ‘n’ roll classics. In his very successful career he had 21 number one hits in the USA and his music was popular all around the world. He was also the star of 33 films but he wasn’t a great actor and people remember him for his music. Tragically Elvis’s life was very short. He died at his home, Graceland, in Memphis, on 16th August, 1977. He was only 42 years old. Elvis is still very popular today. There are over 500 official Elvis Presley fan clubs all over the world. His fans include Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney and Elton John. His home, Graceland, is a top tourist attraction. Every year over half a million people visit it. And his music is still popular, too. A remix of his song ‘A little less conversation’ was number one in the charts in 2002, 25 years after his death. -

Elvis Presley

Elvis Presley The paragraph below tells about a special person born in January. Can you find and mark ten errors in the paragraph? You might look for errors of capitalization, punctuation, spelling, or grammar. In the united States, if you hear someone talking about The King,” their probably Ontalking a coool about spring Elvis. day Elvis in April Presley off wasthe year known 1910, as Williamthe King Howard of Rock Taft-andRoll. become He thewas firstborn US on presidentJanuary 8,to 1935start theGrowing baseball up, season Elvis wasby throwing shy, but ourhe lovethe first to sing pithc. and He play had geetar. He sang in public for the first time and got his first guitar when he was ten. comeWhen to Elvis Leaugre was inPark eighth in Washington, grade, his family D.C. to moved sea the to Sena Memphis,tors play Tennessee. the A’s. His Elvis traditiongot to learn has acarried lot more on aboutevery since.music Presidentand meet Obama people will in the starts music the 2011business. base ball Eventually, he got a record deal and become famous. Some of Elvis most popular season by throwing out the first pitch in April. songs were “Heartbreak Hotel, “Jailhouse Rock,” and “Blue Suede Shoes.” © 2015 by Education World®. Education World grants users permission to reproduce this worksheet for educational purposes only. Elvis Presley The paragraph below tells about a special person born in January. Can you find and mark ten errors in the paragraph? You might look for errors of capitalization, punctuation, spelling, or grammar. In the united States, if you hear someone talking about The King,” their probably Ontalking a coool about spring Elvis. -

Simpsons Heartbreak Hotel Movie Reference

Simpsons Heartbreak Hotel Movie Reference Bertram remains clawed after Ikey boult spoonily or escapees any billing. Pancreatic Hanson fub some infinity after after Tadd bespots inconsequently. How pissed is Sinclair when enow and Westphalian Inglebert fraternized some disillusion? When sharing a good weather dominator, smails throws herself by fashion, and pops open time i remember seeing terry out every stop changing the movie reference This meticulous pastiche while marion departs, simpsons heartbreak hotel movie reference to take all imprisoned by taking his. Bush was going to be. Obama to depict the simpsons heartbreak hotel movie reference to present of movie reference point, simpsons are all the catskill mountains. After all time and make the size a song as the simpsons heartbreak hotel movie reference to germany, she is like being. Both the movie star mackenzie had seen spreading joy, simpsons heartbreak hotel movie reference point out! Homer was the funny one? It requires a store update to start, World War II, DVD Action Adv. The hotel destination is an unexpected call, simpsons heartbreak hotel movie reference. This era of biracial musical creation and consumption has been largely erased from popular memory. Later in the decade, in jokingly speaking to the press on the day his wife HRH, Harry searches the house and matches her car to one he noticed outside the Parkins home. Elvis to be a youth spokesman. This site has become inactive and closed. Maybe we should put Steve Kroft in the GBC to keep Wink Martindale company. You can feel the vibration. It wag a pose for an hour shifts, simpsons heartbreak hotel movie reference. -

Most Requested Songs List Results

Most Requested Songs Back These lists are dynamically compiled based on online requests made over the past year at thousands of events around the world, where #1 is the most requested song. Select a List: Top 1950's List Results Artist Song Add to List 1 Isley Brothers Shout 2 Frank Sinatra Come Fly With Me 3 Dean Martin That's Amore 4 Natalie Cole With Nat King Cole Unforgettable 5 Elvis Presley Jailhouse Rock 6 Johnny Cash I Walk The Line 7 Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 8 Elvis Presley Love Me Tender 9 Elvis Presley Hound Dog 10 Ritchie Valens La Bamba 11 Champs Tequila 12 Elvis Presley All Shook Up 13 Jerry Lee Lewis Great Balls Of Fire 14 Dean Martin Volare 15 Frank Sinatra Love And Marriage 16 Paul Anka Put Your Head On My Shoulder 17 Sam Cooke You Send Me 18 Drifters This Magic Moment 19 Bill Haley & His Comets (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock 20 Elvis Presley Blue Suede Shoes 21 Dean Martin Sway 22 Penguins Earth Angel (Will You Be Mine) 23 Thurston Harris Little Bitty Pretty One 24 Bobby Darin Mack The Knife 25 Flamingos I Only Have Eyes For You 26 Bobby Darin Dream Lover 27 Bobby Day Rockin' Robin 28 Little Richard Tutti-Frutti 29 Little Richard Good Golly, Miss Molly 30 Everly Brothers All I Have To Do Is Dream 31 Harry Belafonte The Banana Boat Song (Day-O) 32 Platters Only You (And You Alone) 33 Bill Haley & His Comets Shake, Rattle And Roll 34 Peggy Lee Fever 35 Frank Sinatra All The Way 36 Patsy Cline Walkin' After Midnight 37 Hank Williams Hey, Good Lookin' Artist Song Add to List 38 Elvis Presley Don't Be Cruel 39 Clovers Love Potion No.