Structure of the Sec23/24–Sar1 Pre-Budding Complex of the COPII Vesicle Coat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mea6 Controls VLDL Transport Through the Coordinated Regulation of COPII Assembly

Cell Research (2016) 26:787-804. npg © 2016 IBCB, SIBS, CAS All rights reserved 1001-0602/16 $ 32.00 ORIGINAL ARTICLE www.nature.com/cr Mea6 controls VLDL transport through the coordinated regulation of COPII assembly Yaqing Wang1, *, Liang Liu1, 2, *, Hongsheng Zhang1, 2, Junwan Fan1, 2, Feng Zhang1, 2, Mei Yu3, Lei Shi1, Lin Yang1, Sin Man Lam1, Huimin Wang4, Xiaowei Chen4, Yingchun Wang1, Fei Gao5, Guanghou Shui1, Zhiheng Xu1, 6 1State Key Laboratory of Molecular Developmental Biology, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; 3School of Life Science, Shandong University, Jinan 250100, China; 4Institute of Molecular Medicine, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China; 5State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; 6Translation- al Medical Center for Stem Cell Therapy, Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200120, China Lipid accumulation, which may be caused by the disturbance in very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion in the liver, can lead to fatty liver disease. VLDL is synthesized in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and transported to Golgi apparatus for secretion into plasma. However, the underlying molecular mechanism for VLDL transport is still poor- ly understood. Here we show that hepatocyte-specific deletion of meningioma-expressed antigen 6 (Mea6)/cutaneous T cell lymphoma-associated antigen 5C (cTAGE5C) leads to severe fatty liver and hypolipemia in mice. Quantitative lip- idomic and proteomic analyses indicate that Mea6/cTAGE5 deletion impairs the secretion of different types of lipids and proteins, including VLDL, from the liver. -

RNF11 at the Crossroads of Protein Ubiquitination

biomolecules Review RNF11 at the Crossroads of Protein Ubiquitination Anna Mattioni, Luisa Castagnoli and Elena Santonico * Department of Biology, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Via della ricerca scientifica, 00133 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (L.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 8 November 2020; Published: 11 November 2020 Abstract: RNF11 (Ring Finger Protein 11) is a 154 amino-acid long protein that contains a RING-H2 domain, whose sequence has remained substantially unchanged throughout vertebrate evolution. RNF11 has drawn attention as a modulator of protein degradation by HECT E3 ligases. Indeed, the large number of substrates that are regulated by HECT ligases, such as ITCH, SMURF1/2, WWP1/2, and NEDD4, and their role in turning off the signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation, candidates RNF11 as the master regulator of a plethora of signaling pathways. Starting from the analysis of the primary sequence motifs and from the list of RNF11 protein partners, we summarize the evidence implicating RNF11 as an important player in modulating ubiquitin-regulated processes that are involved in transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) signaling pathways. This connection appears to be particularly significant, since RNF11 is overexpressed in several tumors, even though its role as tumor growth inhibitor or promoter is still controversial. The review highlights the different facets and peculiarities of this unconventional small RING-E3 ligase and its implication in tumorigenesis, invasion, neuroinflammation, and cancer metastasis. Keywords: Ring Finger Protein 11; HECT ligases; ubiquitination 1. -

S100A8 Transported by SEC23A Inhibits Metastatic Colonization Via

Sun et al. Cell Death and Disease (2020) 11:650 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-02835-w Cell Death & Disease ARTICLE Open Access S100A8 transported by SEC23A inhibits metastatic colonization via autocrine activation of autophagy Zhiwei Sun1,2, Bin Zeng1,2,DoudouLiu1,2, Qiting Zhao1,2,JianyuWang1,2 and H. Rosie Xing2,3 Abstract Metastasis is the main cause of failure of cancer treatment. Metastatic colonization is regarded the most rate- limiting step of metastasis and is subjected to regulation by a plethora of biological factors and processes. On one hand, regulation of metastatic colonization by autophagy appears to be stage- and context-dependent, whereas mechanistic characterization remains elusive. On the other hand, interactions between the tumor cells and their microenvironment in metastasis have long been appreciated, whether the secretome of tumor cells can effectively reshape the tumor microenvironment has not been elucidated mechanistically. In the present study, we have identified “SEC23A-S1008-BECLIN1-autophagy axis” in the autophagic regulation of metastatic colonization step, a mechanism that tumor cells can exploit autophagy to exert self-restrain for clonogenic proliferation before the favorable tumor microenvironment is established. Specifically, we employed a paired lung-derived oligometastatic cell line (OL) and the homologous polymetastatic cell line (POL) from human melanoma cell line M14 that differ in colonization efficiency. We show that S100A8 transported by SEC23A inhibits metastatic colonization via autocrine activation of autophagy. Furthermore, we verified the clinical relevance of our experimental findings by bioinformatics analysis of the expression of Sec23a and S100A8 and the clinical- pathological associations. We demonstrate that higher Sec23a and Atg5 expression levels appear to be protective factors and favorable diagnostic (TNM staging) and prognostic (overall survival) markers for skin cutaneous 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; melanoma (SKCM) and colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) patients. -

Site-1 Protease Deficiency Causes Human Skeletal Dysplasia Due to Defective Inter-Organelle Protein Trafficking

Site-1 protease deficiency causes human skeletal dysplasia due to defective inter-organelle protein trafficking Yuji Kondo, … , Patrick M. Gaffney, Lijun Xia JCI Insight. 2018;3(14):e121596. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.121596. Research Article Cell biology Genetics Graphical abstract Find the latest version: https://jci.me/121596/pdf RESEARCH ARTICLE Site-1 protease deficiency causes human skeletal dysplasia due to defective inter-organelle protein trafficking Yuji Kondo,1 Jianxin Fu,1,2 Hua Wang,3 Christopher Hoover,1,4 J. Michael McDaniel,1 Richard Steet,5 Debabrata Patra,6 Jianhua Song,1 Laura Pollard,7 Sara Cathey,7 Tadayuki Yago,1 Graham Wiley,8 Susan Macwana,8 Joel Guthridge,8 Samuel McGee,1 Shibo Li,3 Courtney Griffin,1 Koichi Furukawa,9 Judith A. James,8 Changgeng Ruan,2 Rodger P. McEver,1,4 Klaas J. Wierenga,3 Patrick M. Gaffney,8 and Lijun Xia1,2,4 1Cardiovascular Biology Research Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA. 2Jiangsu Institute of Hematology, MOH Key Laboratory of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Collaborative Innovation Center of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China. 3Department of Pediatrics and 4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA. 5Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Georgia, Athens, USA. 6Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. 7Greenwood Genetic Center, Greenwood, South Carolina, USA. 8Division of Genomics and Data Sciences, Arthritis and Clinical Immunology Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA. 9Department of Biochemistry II, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan. -

ER-To-Golgi Trafficking and Its Implication in Neurological Diseases

cells Review ER-to-Golgi Trafficking and Its Implication in Neurological Diseases 1,2, 1,2 1,2, Bo Wang y, Katherine R. Stanford and Mondira Kundu * 1 Department of Pathology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN 38105, USA; [email protected] (B.W.); [email protected] (K.R.S.) 2 Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN 38105, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-901-595-6048 Present address: School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361102, China. y Received: 21 November 2019; Accepted: 7 February 2020; Published: 11 February 2020 Abstract: Membrane and secretory proteins are essential for almost every aspect of cellular function. These proteins are incorporated into ER-derived carriers and transported to the Golgi before being sorted for delivery to their final destination. Although ER-to-Golgi trafficking is highly conserved among eukaryotes, several layers of complexity have been added to meet the increased demands of complex cell types in metazoans. The specialized morphology of neurons and the necessity for precise spatiotemporal control over membrane and secretory protein localization and function make them particularly vulnerable to defects in trafficking. This review summarizes the general mechanisms involved in ER-to-Golgi trafficking and highlights mutations in genes affecting this process, which are associated with neurological diseases in humans. Keywords: COPII trafficking; endoplasmic reticulum; Golgi apparatus; neurological disease 1. Overview Approximately one-third of all proteins encoded by the mammalian genome are exported from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and transported to the Golgi apparatus, where they are sorted for delivery to their final destination in membrane compartments or secretory vesicles [1]. -

1 the TRAPP Complex Mediates Secretion Arrest Induced by Stress Granule Assembly Francesca Zappa1, Cathal Wilson1, Giusepp

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/528380; this version posted February 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. The TRAPP complex mediates secretion arrest induced by stress granule assembly Francesca Zappa1, Cathal Wilson1, Giuseppe Di Tullio1, Michele Santoro1, Piero Pucci2, Maria Monti2, Davide D’Amico1, Sandra Pisonero Vaquero1, Rossella De Cegli1, Alessia Romano1, Moin A. Saleem3, Elena Polishchuk1, Mario Failli1, Laura Giaquinto1, Maria Antonietta De Matteis1, 2 1 Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, Pozzuoli (Naples), Italy 2 Federico II University, Naples, Italy 3 Bristol Renal, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, UK Correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/528380; this version posted February 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. The TRAnsport-Protein-Particle (TRAPP) complex controls multiple membrane trafficking steps and is thus strategically positioned to mediate cell adaptation to diverse environmental conditions, including acute stress. We have identified TRAPP as a key component of a branch of the integrated stress response that impinges on the early secretory pathway. TRAPP associates with and drives the recruitment of the COPII coat to stress granules (SGs) leading to vesiculation of the Golgi complex and an arrest of ER export. -

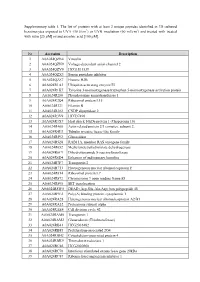

Supplementary Table 1. the List of Proteins with at Least 2 Unique

Supplementary table 1. The list of proteins with at least 2 unique peptides identified in 3D cultured keratinocytes exposed to UVA (30 J/cm2) or UVB irradiation (60 mJ/cm2) and treated with treated with rutin [25 µM] or/and ascorbic acid [100 µM]. Nr Accession Description 1 A0A024QZN4 Vinculin 2 A0A024QZN9 Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 3 A0A024QZV0 HCG1811539 4 A0A024QZX3 Serpin peptidase inhibitor 5 A0A024QZZ7 Histone H2B 6 A0A024R1A3 Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 7 A0A024R1K7 Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein 8 A0A024R280 Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 9 A0A024R2Q4 Ribosomal protein L15 10 A0A024R321 Filamin B 11 A0A024R382 CNDP dipeptidase 2 12 A0A024R3V9 HCG37498 13 A0A024R3X7 Heat shock 10kDa protein 1 (Chaperonin 10) 14 A0A024R408 Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 2, 15 A0A024R4U3 Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family 16 A0A024R592 Glucosidase 17 A0A024R5Z8 RAB11A, member RAS oncogene family 18 A0A024R652 Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 19 A0A024R6C9 Dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase 20 A0A024R6D4 Enhancer of rudimentary homolog 21 A0A024R7F7 Transportin 2 22 A0A024R7T3 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F 23 A0A024R814 Ribosomal protein L7 24 A0A024R872 Chromosome 9 open reading frame 88 25 A0A024R895 SET translocation 26 A0A024R8W0 DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 48 27 A0A024R9E2 Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 28 A0A024RA28 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 29 A0A024RA52 Proteasome subunit alpha 30 A0A024RAE4 Cell division cycle 42 31 -

Conserved Exchange of Paralog Proteins During Neuronal

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.22.453347; this version posted July 23, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Conserved exchange of paralog proteins during neuronal 2 differentiation 3 4 Domenico Di Fraia1, Mihaela Anitei1, Marie-Therese Mackmull*2, Luca Parca*3, Laura 5 Behrendt1, Amparo Andres-Pons4, Darren Gilmour5, Manuela Helmer Citterich3, Christoph 6 Kaether1, Martin Beck6 and Alessandro Ori1# 7 8 Affiliations 9 1 - Leibniz Institute on Aging - Fritz Lipmann Institute (FLI) Beutenbergstraße 1107745 Jena, Germany 10 2 - ETH Zurich Institute of Molecular Systems Biology Otto-Stern-Weg 3, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 11 3 - Department of Biology, University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy 12 4 - European Molecular Biology Laboratory - EMBL, Meyerhofstraße 1, 69117, Heidelberg, Germany 13 5 - University of Zurich, Department of Molecular Life Sciences, Rämistrasse 71 CH-8006 Zürich, Switzerland 14 6 - Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, department of Molecular Sociology, Max-von-Laue-Straße 3, 60438 Frankfurt am Main 15 16 * contributed equally # 17 correspondence to [email protected] 18 19 20 21 22 Abstract 23 Gene duplication enables the emergence of new functions by lowering the general 24 evolutionary pressure. Previous studies have highlighted the role of specific paralog genes 25 during cell differentiation, e.g., in chromatin remodeling complexes. It remains unexplored 26 whether similar mechanisms extend to other biological functions and whether the regulation 27 of paralog genes is conserved across species. -

Craniofacial Diseases Caused by Defects in Intracellular Trafficking

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Craniofacial Diseases Caused by Defects in Intracellular Trafficking Chung-Ling Lu and Jinoh Kim * Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-515-294-3401 Abstract: Cells use membrane-bound carriers to transport cargo molecules like membrane proteins and soluble proteins, to their destinations. Many signaling receptors and ligands are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum and are transported to their destinations through intracellular trafficking pathways. Some of the signaling molecules play a critical role in craniofacial morphogenesis. Not surprisingly, variants in the genes encoding intracellular trafficking machinery can cause craniofacial diseases. Despite the fundamental importance of the trafficking pathways in craniofacial morphogen- esis, relatively less emphasis is placed on this topic, thus far. Here, we describe craniofacial diseases caused by lesions in the intracellular trafficking machinery and possible treatment strategies for such diseases. Keywords: craniofacial diseases; intracellular trafficking; secretory pathway; endosome/lysosome targeting; endocytosis 1. Introduction Citation: Lu, C.-L.; Kim, J. Craniofacial malformations are common birth defects that often manifest as part of Craniofacial Diseases Caused by a syndrome. These developmental defects are involved in three-fourths of all congenital Defects in Intracellular Trafficking. defects in humans, affecting the development of the head, face, and neck [1]. Overt cranio- Genes 2021, 12, 726. https://doi.org/ facial malformations include cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P), cleft palate alone 10.3390/genes12050726 (CP), craniosynostosis, microtia, and hemifacial macrosomia, although craniofacial dys- morphism is also common [2]. -

TANGO1/Ctage5 Receptor As a Polyvalent Template for Assembly of Large COPII Coats

TANGO1/cTAGE5 receptor as a polyvalent template for assembly of large COPII coats Wenfu Maa,b and Jonathan Goldberga,b,1 aHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065; and bStructural Biology Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065 Edited by David J. Owen, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Pietro De Camilli July 9, 2016 (received for review April 12, 2016) The supramolecular cargo procollagen is loaded into coat protein COPII carrier (9). Alternatively, TANGO1/cTAGE5 might con- complex II (COPII)-coated carriers at endoplasmic reticulum (ER) exit stitute machinery that switches COPII coat assembly from small sites by the receptor molecule TANGO1/cTAGE5. Electron micros- spherical vesicles to large carriers, but such a mechanism has not copy studies have identified a tubular carrier of suitable dimensions been explored to date. Important in this respect is the observation that is molded by a distinctive helical array of the COPII inner coat of tubular COPII carriers with dimensions commensurate with protein Sec23/24•Sar1; the helical arrangement is absent from ca- procollagen cargo; such tubules form, along with small vesicles, in nonical COPII-coated small vesicles. In this study, we combined X-ray budding reactions in vivo and in vitro (14–16). COPII-coated tu- crystallographic and biochemical analysis to characterize the associ- bules are observed as straight-sided tubes (17), or with a beads-on- ation of TANGO1/cTAGE5 with COPII proteins. The affinity for Sec23 a-string appearance in which regular constrictions may arise from is concentrated in the proline-rich domains (PRDs) of TANGO1 and aborted attempts at membrane fission (14, 16). -

Membrane Trafficking in Health and Disease Rebecca Yarwood*, John Hellicar*, Philip G

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Disease Models & Mechanisms (2020) 13, dmm043448. doi:10.1242/dmm.043448 AT A GLANCE Membrane trafficking in health and disease Rebecca Yarwood*, John Hellicar*, Philip G. Woodman‡ and Martin Lowe‡ ABSTRACT KEY WORDS: Disease, Endocytic pathway, Genetic disorder, Membrane traffic, Secretory pathway, Vesicle Membrane trafficking pathways are essential for the viability and growth of cells, and play a major role in the interaction of cells with Introduction their environment. In this At a Glance article and accompanying Membrane trafficking pathways are essential for cells to maintain poster, we outline the major cellular trafficking pathways and discuss critical functions, to grow, and to accommodate to their chemical how defects in the function of the molecular machinery that mediates and physical environment. Membrane flux through these pathways this transport lead to various diseases in humans. We also briefly is high, and in specialised cells in some tissues can be enormous. discuss possible therapeutic approaches that may be used in the For example, pancreatic acinar cells synthesise and secrete amylase, future treatment of trafficking-based disorders. one of the many enzymes they produce, at a rate of approximately 0.5% of cellular protein mass per hour (Allfrey et al., 1953), while in Schwann cells, the rate of membrane protein export must correlate School of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, with the several thousand-fold expansion of the cell surface that University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PT, UK. occurs during myelination (Pereira et al., 2012). The population of *These authors contributed equally to this work cell surface proteins is constantly monitored and modified via the ‡Authors for correspondence ([email protected]; endocytic pathway. -

Perkinelmer Genomics to Request the Saliva Swab Collection Kit for Patients That Cannot Provide a Blood Sample As Whole Blood Is the Preferred Sample

Autism and Intellectual Disability TRIO Panel Test Code TR002 Test Summary This test analyzes 2429 genes that have been associated with Autism and Intellectual Disability and/or disorders associated with Autism and Intellectual Disability with the analysis being performed as a TRIO Turn-Around-Time (TAT)* 3 - 5 weeks Acceptable Sample Types Whole Blood (EDTA) (Preferred sample type) DNA, Isolated Dried Blood Spots Saliva Acceptable Billing Types Self (patient) Payment Institutional Billing Commercial Insurance Indications for Testing Comprehensive test for patients with intellectual disability or global developmental delays (Moeschler et al 2014 PMID: 25157020). Comprehensive test for individuals with multiple congenital anomalies (Miller et al. 2010 PMID 20466091). Patients with autism/autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Suspected autosomal recessive condition due to close familial relations Previously negative karyotyping and/or chromosomal microarray results. Test Description This panel analyzes 2429 genes that have been associated with Autism and ID and/or disorders associated with Autism and ID. Both sequencing and deletion/duplication (CNV) analysis will be performed on the coding regions of all genes included (unless otherwise marked). All analysis is performed utilizing Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology. CNV analysis is designed to detect the majority of deletions and duplications of three exons or greater in size. Smaller CNV events may also be detected and reported, but additional follow-up testing is recommended if a smaller CNV is suspected. All variants are classified according to ACMG guidelines. Condition Description Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a group of developmental disabilities that are typically associated with challenges of varying severity in the areas of social interaction, communication, and repetitive/restricted behaviors.