Playing It for Real – Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elgar Chadwick

ELGAR Falstaff CHADWICK Tam O’Shanter Andrew Constantine BBC National Orchestra of Wales Timothy West Samuel West CD 1 CD 2 Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Falstaff – Symphonic Study in C minor, Op.68 Falstaff – Symphonic Study in C minor, Op.68 1 I am not only witty in myself, but the cause that wit is in other men 3.59 1 Falstaff and Prince Henry 3.05 2 Falstaff and Prince Henry 3.02 2 Eastcheap - the robbery at Gadshill - The Boar’s Head - revelry and sleep 13.25 3 What’s the matter? 3.28 3 Dream interlude: ‘Jack Falstaff, now Sir John, a boy, 4 Eastcheap - the robbery at Gadshill - The Boar’s Head - and page to Sir Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk 2.35 revelry and sleep 13.25 4 Falstaff’s March - The return through Gloucestershire 4.12 5 Dream interlude: ‘Jack Falstaff, now Sir John, a boy, and page to Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk’ 2.37 5 Interlude: Gloucestershire. Shallow’s orchard - The new king - The hurried ride to London 2.45 6 Come, sir, which men shall I have? 1.43 6 King Henry V’s progress - The repudiation of Falstaff and his death 9.22 7 Falstaff’s March - The return through Gloucestershire 4.12 8 Interlude: Shallow’s orchard - The new king - Total time 35.28 The hurried ride to London 2.44 BBC National Orchestra of Wales 9 Sir John, thy tender lambkin now is king. Harry the Fifth’s the man 2.24 Andrew Constantine 10 King Henry V’s progress - The repudiation of Falstaff and his death 9.25 George Whitefield Chadwick (1854-1931) Tam O’Shanter 11 Chadwick’s introductory note to Tam O’Shanter 4.32 12 Tam O’Shanter 19.39 Total time 71.14 BBC National Orchestra of Wales Andrew Constantine Falstaff, Timothy West Prince Henry, Samuel West George Whitefield Chadwick, Erik Chapman Robert Burns, Billy Wiz 2 Many of you might be coming to Elgar’s great masterpiece Falstaff for the very first time - I truly hope so! It has, undeniably, had a harder time working its way into the consciousness of the ‘Elgar-lover’ than most of his other great works. -

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

To Download Rupert Christiansen's Interview

Collection title: Behind the scenes: saving and sharing Cambridge Arts Theatre’s Archive Interviewee’s surname: Christiansen Title: Mr Interviewee’s forename(s): Rupert Date(s) of recording, tracks (from-to): 9.12.2019 Location of interview: Cambridge Arts Theatre, Meeting Room Name of interviewer: Dale Copley Type of recorder: Zoom H4N Recording format: WAV Total no. of tracks: 1 Total duration (HH:MM:SS): 00:31:25 Mono/Stereo: Stereo Additional material: None Copyright/Clearance: Assigned to Cambridge Arts Theatre. Interviewer’s comments: None Abstract: Opera critic/writer and Theatre board member, Rupert Christiansen first came the Theatre in 1972. He was a regular audience member whilst a student at Kings College, Cambridge and shares memories of the Theatre in the 1970s. Christiansen’s association was rekindled in the 1990s when he was employed to author a commemorative book about the Theatre. He talks about the research process and reflects on the redevelopment that took place at this time. He concludes by explaining how he came to join the Theatre’s board. Key words: Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company, Elijah Moshinsky, Sir Ian McKellen, Felicity Kendall, Contemporary Dance Theatre, Andrew Blackwood, Judy Birdwood, costume, Emma Thompson, Hugh Laurie, Stephen Fry, Peggy Ashcroft and Alec Guinness, Cambridge Footlights, restaurant, The Greek Play, ETO, Kent Opera and Opera 80, Festival Theatre, Sir Ian McKellen, Eleanor Bron. Picturehouse Cinema, File 00.00 Christiansen introduces himself. His memories of the Theatre range from 1972 to present, he is now on the Theatre’s board of trustees. Christiansen describes his first experience of the Theatre seeing a production of ‘As You Like It’ featuring his school friend Sophie Cox as Celia, by the Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company and directed by Elijah Moshinsky [b. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

ESTELLE PARSONS & NAOMI LIEBLER Monday, April 13

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION THE LAMBS, NEW YORK CITY ESTELLE PARSONS & NAOMI LIEBLER Monday, April 13 For this special gathering, the GUILD is delighted to join forces with THE LAMBS, a venerable theatrical society whose early leaders founded Actors’ Equity, ASCAP, and the Screen Actors Guild. Hal Holbrook offered Mark Twain Tonight to his fellow Lambs before taking the show public. So it’s hard to imagine a better THE LAMBS setting for ESTELLE PARSONS and NAOMI LIEBLER to present 3 West 51st Street a dramatic exploration of “Shakespeare’s Old Ladies.” A Manhattan member of the American Theatre Hall of Fame and a PROGRAM 7:00 P.M. former head of The Actors Studio, Ms. Parsons has been Members $5 nominated for five Tony Awards and earned an Oscar Non-Members $10 as Blanche Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Dr. Liebler, a professor at Montclair State, has given us such critically esteemed studies as Shakespeare’s Festive Tragedy. Following their dialogue, a hit in 2011 at the New York Public Library, they’ll engage in a wide-ranging conversation about its key themes. TERRY ALFORD Tuesday, April 14 To mark the 150th anniversary of what has been called the most dramatic moment in American history, we’re pleased to host a program with TERRY ALFORD. A prominent Civil War historian, he’ll introduce his long-awaited biography of an actor who NATIONAL ARTS CLUB co-starred with his two brothers in a November 1864 15 Gramercy Park South benefit of Julius Caesar, and who restaged a “lofty Manhattan scene” from that tragedy five months later when he PROGRAM 6:00 P.M. -

March 2016 Conversation

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE WNDC IN WASHINGTON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION DIANA OWEN ♦ Tuesday, February 23 As we commemorate SHAKESPEARE 400, a global celebration of the poet’s life and legacy, the GUILD is delighted to co-host a WOMAN’S NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CLUB gathering with DIANA OWEN, who heads the SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST in Stratford-upon-Avon. The TRUST presides over such treasures as Mary Arden’s House, WITTEMORE HOUSE Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and the home in which the play- 1526 New Hampshire Avenue wright was born. It also preserves the site of New Place, the Washington mansion Shakespeare purchased in 1597, and in all prob- LUNCH 12:30. PROGRAM 1:00 ability the setting in which he died in 1616. A later owner Luncheon & Program, $30 demolished it, but the TRUST is now unearthing the struc- Program Only , $10 ture’s foundations and adding a new museum to the beautiful garden that has long delighted visitors. As she describes this exciting project, Ms. Owen will also talk about dozens of anniversary festivities, among them an April 23 BBC gala that will feature such stars as Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen. PEGGY O’BRIEN ♦ Wednesday, February 24 Shifting to the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY, an American institution that is marking SHAKESPEARE 400 with a national tour of First Folios, we’re pleased to welcome PEGGY O’BRIEN, who established the Library’s globally acclaimed outreach initiatives to teachers and NATIONAL ARTS CLUB students in the 1980s and published a widely circulated 15 Gramercy Park South Shakespeare Set Free series with Simon and Schuster. -

Favourite Poems for Children Favourite Poems For

Favourite Poems JUNIOR CLASSICS for Children The Owl and the Pussycat • The Pied Piper of Hamelin The Jumblies • My Shadow and many more Read by Anton Lesser, Roy McMillan, Rachel Bavidge and others 1 The Lobster Quadrille Lewis Carroll, read by Katinka Wolf 1:58 2 The Walrus and the Carpenter Lewis Carroll, read by Anton Lesser 4:22 3 You Are Old, Father William Lewis Carroll, read by Roy McMillan 1:46 4 Humpty Dumpty’s Song Lewis Carroll, read by Richard Wilson 2:05 5 Jabberwocky Lewis Carroll, read by David Timson 1:33 6 Little Trotty Wagtail John Clare, read by Katinka Wolf 0:51 7 The Bogus-Boo James Reeves, read by Anton Lesser 1:17 8 A Tragedy in Rhyme Oliver Herford, read by Anton Lesser 2:25 9 A Guinea Pig Song Anonymous, read by Katinka Wolf 0:47 10 The Jumblies Edward Lear, read by Anton Lesser 4:06 2 11 The Owl and the Pussycat Edward Lear, read by Roy McMillan 1:35 12 Duck’s Ditty Kenneth Grahame, read by Katinka Wolf 0:40 13 There was an Old Man with a Beard Edward Lear, read by Roy McMillan 0:17 14 Old Meg John Keats, read by Anne Harvey 1:24 15 How Pleasant to Know Mr Lear Edward Lear, read by Roy McMillan 1:31 16 There was a naughty boy John Keats, read by Simon Russell Beale 0:35 17 At the Zoo William Makepeace Thackeray, read by Roy McMillan 0:29 18 Dahn the Plug’ole Anonymous, read by Anton Lesser 1:14 19 Henry King Hilaire Belloc, read by Katinka Wolf 0:47 20 Matilda Hilaire Belloc, read by Anne Harvey 2:35 3 21 The King’s Breakfast A.A. -

“Revenge in Shakespeare's Plays”

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “OTHELLO” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: 1603-1604…. although some critics place the date somewhat earlier in 1601- 1602 mainly on the basis of some “echoes” of the play in the 1603 “bad” quarto of “Hamlet”. AGE: 39-40 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Four years after “Hamlet”; first in the consecutive series of tragedies followed by “King Lear”, “Macbeth” then “Antony and Cleopatra”. GENRE: “The Great Tragedies” SOURCES: An Italian tale in the collection “Gli Hecatommithi” (1565) of Giovanni Battista Giraldi (writing under the name Cinthio) from which Shakespeare also drew for the plot of “Measure for Measure”. John Pory’s 1600 translation of John Leo’s “A Geographical History of Africa”; Philemon Holland’s 1601 translation of Pliny’s “History of the World”; and Lewis Lewkenor’s 1599 “The Commonwealth and Government of Venice” mainly translated from a Latin text by Cardinal Contarini. STRUCTURE: “More a domestic tragedy than ‘Hamlet’, ‘Lear’ or ‘Macbeth’ concentrating on the destruction of Othello’s marriage and his murder of his wife rather than on affairs of state and the deaths of kings”. SUCCESS: The tragedy met with high success both at its initial Globe staging and well beyond mainly because of its exotic setting (Venice then Cypress), the “foregrounding of issues of race, gender and sexuality”, and the powerhouse performance of Richard Burbage, the most famous actor in Shakespeare’s company. HIGHLIGHT: Performed at the Banqueting House at Whitehall before King James I on 1 November 1604. AFTER: The play has been performed steadily since 1604; for a production in 1660 the actress Margaret Hughes as Desdemona “could have been the first professional actress on the English stage”. -

Soil Profiles in Film (PDF)

Project FOCUS Best Lessons MIDDLE SCHOOL Title of Lesson: The Circle of Life: Soil Profiles Theme: Earth/Space Science Unit Number: I Unit Title: The Earth's Surface Performance Standard(s) Covered (enter code): S6E5. Students will investigate the scientific view of how the earth’s surface is formed. Enduring Standards (objectives of activity): Habits of Mind ☒ Asks questions ☐ Uses numbers to quantify ☐ Works in a group ☐ Uses tools to measure and view ☐ Looks at how parts of things are needed ☒ Describes and compares using physical attributes ☐ Observes using senses ☒ Draws and describes observations Content (key terms and topics covered): This lesson covers soil profiles and how they can change in depth or nutrient composition based on changes in vegetation and even animal activity. It is important the students already have an understanding of soil profiles and the vocabulary associated with them. This lesson is more of a review. Learning Activity (description in steps) Abstract (limit 100 characters): This lesson is designed to look at a single habitat that has been drastically changed. By using the scenes from "The Lion King" students can see how habitats can change in composition of vegetation which can change the depth of the layers in the soil profile. At the end of this lesson the students should have a clear understanding of how vegetation adds nutrients and volume to the top soil profile. Some other areas this lesson can be expanded to is fossils. Details: Have the students in desks throughout the room and stress to them the importance of raising their hand when answering. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

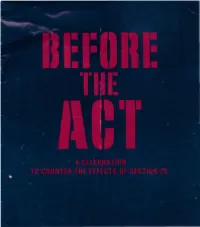

Before-The-Act-Programme.Pdf

Dea F ·e s. Than o · g here tonight and for your Since Clause 14 (later 27, 28 and 29) was an contribution o e Organisation for Lesbian and Gay nounced, OLGA members throughout the country Action (OLGA) in our fight against Section 28 of the have worked non-stop on action against it. We raised Local Govern en Ac . its public profile by organising the first national Stop OLGA is a a · ~ rganisa ·o ic campaigns The Clause Rally in January and by organising and on iss es~ · g lesbians and gay e . e ber- speaking at meetings all over Britain. We have s ;>e o anyone who shares o r cancer , lobbied Lords and MPs repeatedly and prepared a e e eir sexuality, and our cons i u ion en- briefings for them , for councils, for trade unions, for s es a no one political group can take power. journalists and for the general public. Our tiny make C rre ly. apart from our direct work on Section 28, shift office, staffed entirely by volunteers, has been e ave th ree campaigns - on education , on lesbian inundated with calls and letters requ esting informa cus ody and on violence against lesbians and gay ion and help. More recently, we have also begun to men. offer support to groups prematurely penalised by We are a new organisation, formed in 1987 only local authorities only too anxious to implement the days before backbench MPs proposed what was new law. then Clause 14, outlawing 'promotion' of homosexu The money raised by Before The Act will go into ality by local authorities.