Whittingham Lane, Goosnargh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. Network Planning for Walking

Central Lancashire Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan 5. Network Planning for Walking The future walking network has been derived through identifying those areas which would benefit from creating a sustainable link between trip origins and trip destinations within a reasonable walking distance of approximately 2km. Trip origins predominantly include densely populated residential areas and trip destinations include educational, employment and retail areas which are likely to attract a significant number of trips. As part of this process, funnel routes have been identified which incorporate the route which most pedestrians will follow to access a particular destination, however given the diverse nature of pedestrian movements, the routes do not extend into particular destinations since the route of each individual user will vary depending on their individual trip origin/end. In alignment with LCWIP guidance, Core Walking Zones have also been identified from identifying the area within each town which encompasses the greatest amount of trip attractors and therefore likely the generate the greatest levels of walking. The Four Core Walking Zones (CWZ) identified are: • Preston CWZ; • Lostock Hall CWZ; • Leyland CWZ; and • Chorley CWZ. 41 Central Lancashire Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan 5.1 Proposed Walking Routes 5.1.1 Preston Core Walking Zone Figure 5-1 Preston CWZ / Funnel Routes The Preston CWZ proposals will improve facilities for both pedestrians and cyclists alike, making it safer and easier to access Preston inner city centre, UCLAN, Cardinal Newman College, and transport hubs such as Preston Railway and Bus Stations. Measures predominantly involve pedestrian priority / informal streets, to improve the safety and accessibility of the town centre for pedestrians. -

Central Lancashire Open Space Assessment Report

CENTRAL LANCASHIRE OPEN SPACE ASSESSMENT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk Quality assurance Name Date Report origination AL / CD July 2018 Quality control CMF July 2018 Client comments Various Sept/Oct/Nov/Dec 2018 Revised version KKP February 2019 Agreed sign off April 2019 Contents PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Report structure ...................................................................................................... 2 1.2 National context ...................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Local context ........................................................................................................... 3 PART 2: METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Analysis area and population .................................................................................. 4 2.2 Auditing local provision (supply) .............................................................................. 6 2.3 Quality and value .................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Quality and value thresholds .................................................................................. -

North Road Retail Park North Road, Preston, Pr1 1Ru

NORTH ROAD RETAIL PARK NORTH ROAD, PRESTON, PR1 1RU On behalf of the Joint Administrators, A P Berry & M J Magnay www.avisonyoungretail.co.uk INVESTMENT NORTH ROAD RETAIL PARK SUMMARY INVESTMENT SUMMARY ■ Preston is the principal commercial and ■ Preston benefits from excellent road communications ■ North Road Retail Park is fully let with a total administrative centre for Lancashire, with a primary with easy access from the M6, M61, M65, income of £217,000 per annum. catchment population of 338,000 people. and M55 motorways. ■ The park totals 21,554 sq ft and is occupied ■ The park is prominently located on the A6, which is ■ North Road Retail Park is a modern scheme having by Evans Cycles and Pure Gym. the main road into Preston from the M55 to the north. been developed in 2014. ■ The scheme has a WAULT of 6.7 years to expiry ■ Asset management opportunities include repurposing and 3.7 years to break. the scheme and potential for redevelopment of the ■ The Pure Gym lease benefits from a fixed uplift overflow car park. on 12 October 2024 to £145,200 per annum. ■ Freehold. Offers sought in excess of £2,044,000 (Two Million and Forty Four Thousand Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level would reflect an attractive net initial yield of 10.00% after purchaser’s costs of 6.16%. Based on the fixed uplift in the Pure Gym lease, the reversionary yield will rise to 10.60% in October 2024. The overflow car park is available for a consideration of£100,000 , giving a total lot size of £2,144,000 (Two Million, One Hundred and Forty Four Thousand Pounds). -

Uclan Moor Park Walk Approx. 2.5 Miles/35-40 Minutes Uclan Lancaster Canal Walk Approx. 1.5 Miles/20-25 Minutes Uclan Lancaster

UCLan Moor Park Walk UCLan Lancaster Canal Walk UCLan Moor Park Walk UCLan Lancaster Canal Walk Approx. 2.5 miles/35-40 minutes Approx. 1.5 miles/20-25 minutes Points of interest Points of interest Moor Park is Preston’s oldest and largest park, in the past the park has been St. Walburge’s Church has the tallest parish church spire in England, 307 feet. host to horse races 1736-1833 and a hospital during the First World War, as well The church is one of Preston’s greatest historic buildings and the architect also as open air baths in 1907. In 1833 Preston became the first of the new industrial designed the hansom cab. towns to create a municipal park by enclosing 100 acres of Preston Moor and The Lancaster Canal stretches nearly 42 miles from Preston to Tewitfield, renaming it Moor Park. construction began in 1792 due to the industrial demand for transport between In 1997 Tom Benson became the new world champion distance walker by walking Preston, Manchester and Lancaster. This canal previously continued to the centre the perimeter of the park covering a total of 314 miles. The observatory was built of Preston and most of the ground formerly occupied by the canal basin is now in time for the 1927 total eclipse of the sun and UCLan now own the observatory. UCLan Campus. Located at the far side of the park is the Preston North End football ground; they were a founder member of the English Football League in 1888 and were the first Directions English football champions. -

Council for Voluntary Service Central Lancashire Registered Charity No. 222247 Celebrating 78 Years of Service

Council for Voluntary Service Central Lancashire Registered Charity No. 222247 Celebrating 78 years of service “Promoting and assisting voluntary and community activity in Preston” 1934-2012 serving Chorley and South Ribble since 2011 Annual Report & Accounts 2011/2012 “Working with you, for you!” About Us… The Trustees of the Council for Voluntary Service Central Lancashire submit their report for the year ended 31 st March 2012. REGISTERED OFFICE OF THE CHARITY: Units 23-27 Guild Hall Arcade Lancaster Road Preston PR1 1HR Telephone: 01772 251108 Fax: 01772 251170 Email: [email protected] Website: www.prestoncvs.org Registered Charity No. 222247 STAFF: Chief Officer Joan Burrows Administrative Assistant (Assisted Placement) Simon Fowler Administrative Officer (Future Jobs Fund) James Snape up to May ‘11 Administrative Officer (Future Jobs Fund) Chloe Thornton up to May ‘11 Information and Support Officer John Freeman up to May ‘11 Grants/Community Inclusion Officer Ian Ferguson Volunteering and Public Relations Officer Mark Waddington DRIVE Project Co-ordinator Janet Dand from Dec ‘11 Domestic Stella Swift We would like to express our sincere thanks to the volunteers who have assisted us in our work: Lynn Silver, Abir Ahmed, William Dobson, Nicola Haselden, Janet Whitfield, Joan Speirs, Rose Pearse, Arron Riley, Paul Wilkins, Daniel Sullivan, David Parker, Amanda Sinclare, Michael Gardner, Eileen Bullock, Christelle Agarat, Robert Williams and Charlotte Loughran who assisted with administration and Edward, Freddie and Colin (HMP Kirkham) for their assistance with administration and event support and for their DIY skills. We acknowledge the continuing support from Remploy Primeforce (assisted staff placement) and we have welcomed being involved in assisting Age UK, formerly Age Concern Lancashire, Youth Employment Training Scheme by providing a work based placement for Bradley O’Loughlin. -

Central Lancashire Economic Regeneration Strategy 2026

Economy Places People Central Lancashire Economic Regeneration Strategy 2026 Central Lancashire Economic Regeneration Strategy 2026 Contents: Executive summary 1. Introduction 2. Vision 3. Central Lancashire Today 4. Areas for Action A-Z 5. Economic priorities 6. Opportunities to make a difference 7. Collaborative Working 8. Driving Central Lancashire Forward 9. Projects Supporting Economic Growth 10. Delivery 11. Measurement 12. Implementation Appendices 1. Strategic Fit 2. Measurement 3. Baseline Research 4. Central Lancashire Baseline Economic Research Summary 5. Action Plan Template May 2010 Central Lancashire Economic Regeneration Strategy v4-2 Approved JClough May 2010 2 Executive Summary Our priorities for Central Lancashire include: attracting investment, increasing productivity, raising skills and qualification rates, improving sustainable transport and communications, increasing energy efficiency, securing and creating new jobs and enhancing local places and services. Highlights include: A strong and prosperous economy • Delivering targeted support to grow strong local sectors • Generating and sustaining new business starts and increasing inward investment • Supporting a viable rural economy including diversification and increasing food security • Increasing energy efficiency in businesses through promotion of energy efficient design Future Investment • Delivering development of the Strategic Regional Employment Sites • Providing complementary employment sites to provide a long-term attractive supply Infrastructure Improvement -

Saturday 14 and Sunday 15 September 2019 Events from Friday 13 to Sunday 22 September

The weekend is co-ordinated by Preston History Network and supported by UCLan, Preston CC, Winckley Square CIC and Friends. Thank you to all the sites for their enthusiastic participation. #HODsPreston Saturday 14andSunday 15September 2019 Step through historic doors into some of Step throughhistoric doorsintosomeof Events from Friday13toSunday 22September Preston’s fascinating buildings www.visitpreston.com Use the map to find your way around! Art Direction and Design: madebymason.co.uk @made_by_mason on instagram Discover Dob Croft Lancashire Archives Welcome to Preston Intact, 49 Whitby Avenue, Jeremiah Horrocks Bow Lane, PR1 2RE and 30 fascinating Ingol, PR2 3YP Observatory Moor Park, off Blackpool heritage sites with The Archives are marking the Dob Croft nature reserve is on the /Garstang Roads PR1 1NN Peterloo massacre in 1819 with stories to tell. site of the former brickworks in Ingol, and displays of the personal papers of orator home to the Great Crested Newt. Tours of Visit the observatory in Moor Park, named Henry Hunt, and magistrate William Hulton, Dob Croft, a history talk, and family friendly after the Lancashire astronomer who who ordered the yeomanry intervention. Explore the city centre and activities reveal the natural, industrial and first observed the transit of Venus. It was Take a tour behind the scenes and see more built in 1927 and houses a historic Cooke beyond, and discover places and social heritage of this site. treasures in a strongroom. Listen to creative 8 inch refractor telescope, and displays of responses to Peterloo at 2pm. history you never knew about 2 – 5pm meteorites and astronomical history. -

Central Lancashire Strategy & Action Plan December 2018

CENTRAL LANCASHIRE STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN DECEMBER 2018 QUALITY, INTEGRITY, PROFESSIONALISM Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk CENTRAL LANCASHIRE STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. 1 GLOSSARY ...................................................................................................................... 2 PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 PART 2: VISION ............................................................................................................. 13 PART 3: AIMS ................................................................................................................ 14 PART 4: SPORT SPECIFIC ISSUES SCENARIOS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .......... 15 PART 5: STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................... 46 PART 6: ACTION PLAN ................................................................................................. 62 PART 7: CHORLEY ACTION PLAN ............................................................................... 65 PART 8: PRESTON ACTION PLAN ............................................................................... 86 PART 9: SOUTH RIBBLE ACTION PLAN ................................................................... -

Central Lancashire Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document (SPD)

Central Lancashire Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) Final Version October 2012 SOUTH RIBBLE BOROUGH COUNCIL forward with South Ribble Central Lancashire Design Guide SPD October 2012 3 Contents Part1: Introduction Page 4 Purpose Page 7 Structure of the Design SPD Page 8 Part 2: The Character of Central Lancashire Page 10 Preston Page 13-18 Chorley Page 19-22 South Ribble Page 23-26 Part 3: The Design Principles Page 27 1. Movement and Legibility Page 32-33 2. Space and Enclosure Page 34-35 3. Mixed Uses and Tenures Page 36-37 4. Adaptability and Resilience Page 38-39 5. Resources and Efficiency Page 40-41 6. Architecture and Townscape Page 42-43 Part 4: The Design Process Page 44 Develop a Design Proposal Page 44 Appraise the Issues Page 44-48 Develop a Design Concept Plan Page 49 Design and access Statements Page 53-54 Design Review Page 55 Assessing the Information Page 56 5.1: Sustainability Appraisal and Habitats Regulations Assessment Page 58 5.2: Monitoring and Review Page 58 5.3: Status of SPDs Page 58 5.4: Further Information Page 59 Appendix 1: Assessment Criteria Page 60-65 Appendix 2: Quality-Reviewer Table Page 66-67 Appendix 3: Glossary Page 68-69 Appendix 4: References and Further Reading Page 70-71 Contents Page 4 Central Lancashire Design Guide SPD October 2012 5 1.6. The Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) for the North West places an emphasis 1: Introduction on the need for urban regeneration and renaissance to enhance quality of life in the region. -

Central Lancashire Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document (SPD)

Central Lancashire Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) Final Version October 2012 SOUTH RIBBLE BOROUGH COUNCIL forward with South Ribble Central Lancashire Design Guide SPD October 2012 3 Contents Part1: Introduction Page 4 Purpose Page 7 Structure of the Design SPD Page 8 Part 2: The Character of Central Lancashire Page 10 Preston Page 13-18 Chorley Page 19-22 South Ribble Page 23-26 Part 3: The Design Principles Page 27 1. Movement and Legibility Page 32-33 2. Space and Enclosure Page 34-35 3. Mixed Uses and Tenures Page 36-37 4. Adaptability and Resilience Page 38-39 5. Resources and Efficiency Page 40-41 6. Architecture and Townscape Page 42-43 Part 4: The Design Process Page 44 Develop a Design Proposal Page 44 Appraise the Issues Page 44-48 Develop a Design Concept Plan Page 49 Design and access Statements Page 53-54 Design Review Page 55 Assessing the Information Page 56 5.1: Sustainability Appraisal and Habitats Regulations Assessment Page 58 5.2: Monitoring and Review Page 58 5.3: Status of SPDs Page 58 5.4: Further Information Page 59 Appendix 1: Assessment Criteria Page 60-65 Appendix 2: Quality-Reviewer Table Page 66-67 Appendix 3: Glossary Page 68-69 Appendix 4: References and Further Reading Page 70-71 Contents Page 4 Central Lancashire Design Guide SPD October 2012 5 1.6. The Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) for the North West places an emphasis 1: Introduction on the need for urban regeneration and renaissance to enhance quality of life in the region. -

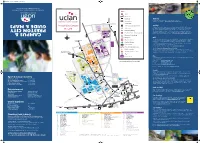

Campus & Preston City Guide & Maps

A2 map 2014_Layout 1 30/06/2014 15:08 Page 1 k u . c a . n a l c u . w w w 1 0 2 1 0 2 2 7 7 1 0 : l e T E H 2 1 R P , n o t s e r P , e r i h s a c n a L l a r t n e C f o y t i s r e v i n U ATM Bus routes Bus stops Walking Fit more walking into your daily life and reap the health benefits. 123 Bus number Walking routes and maps at www.uclan.ac.uk/sustainabletravel s p a m & e d i u G eat@UCLan Cycle compounds/lockers* Cycling Cycling is a great way of commuting as it is often quicker than other modes and a cheap and y t i C n o t s e r p Cycle racks healthy option. Preston and South Ribble benefit from over 50 km of traffic-free cycle paths PR1 2HE and a campus 20mph zone means that is has become safer to cycle on the roads too. Disabled parking The University's Bicycle User Group (BUG) has lots of information on cycling including shower & s u p m a C 4 Electric vehicle charging points and locker locations, information on free cycle training and guidance on bike security and safety. 4A For more information on UCLan cycle facilities visit www.uclan.ac.uk/sustainabletravel 40 23 41 Entrance to buildings 44 Mailroom Rail The University is conveniently situated within walking distance of Preston railway station making UCLan Sports Arena Ri Main reception the train an excellent mode for getting to UCLan. -

Central Lancashire Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan Appendix a P1

Central Lancashire Walking and Cycling Delivery Plan Appendix A. Cycling Route Interventions Document No. ROUTE 1 Scheme Description (£) type cost Reference description level Synergies Scheme location/section High Scheme scheme Preston New Road from A583, Blackpool Rd junction to New/upgraded dedicated Replace existing on‐road mandatory lane with dedicated 2 way off‐road cycle track in R1a.1 W&C £840,000 Lytham Road, Freckleton walking / cycling facility accordance with guidance (approx 4200m) A583, Blackpool Road from Preston New Road junction New/upgraded dedicated R1a.2 Upgrade existing 2 way off‐road cycle track in accordance with guidance (approx 3000m) W&C £400,000 to Nelson Way walking / cycling facility A583, Blackpool Road from Preston New Road junction R1a.3 Maintenance works Route deteriorating in parts and requires some resurfacing works W&C £100,000 to Nelson Way At Junction of Blackpool Road & Riversway (R3) provide dedicated crossing facility for A583, Blackpool Road from Preston New Road junction R1a.4 New ped/cyc crossing those travelling from Blackpool Road area of Preston. Replacing current informal crossings W £175,000 to Nelson Way of dual carriageway Riversway from Nelson Way to Portway West Strand New/upgraded dedicated Construct new 2 way cycle track in accordance with guidance replacing existing advisory R1a.5 W & C £400,000 A5072 walking / cycling facility lane and section where no facility (approx 2000m) Riversway from Nelson Way to Portway West Strand Public realm / streetscape Upgrade subway to link to Rylands