Crowmarsh Gifford (Oct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOTE for COUNCILLOR ROBIN BENNETT Oxfordshire County Council Elections, May 6Th

Newsletter Delivered by GREEN view Royal Mail South oxfordshire Cllr Robin Bennett THE BALDONS - BERINSFIELD – BURCOT - CHISelHAMPTON – CLIFTON HAMPDEN - CULHAM - DORCHESTER ON THAMES – DRAYTON ST LEONARD GARSINGTON – Newington - NUNEHAM COURTENAY – Sandford on thames – shillingford – STADHAMPTON – warborough VOTE FOR COUNCILLOR ROBIN BENNETT Oxfordshire County Council elections, May 6th Expressway by stealth? COVID-19 SUPPORT One of Councillor Robin’s first actions when elected in 2019 was to confirm the District Council’s opposition to the SODC Community Hub: Oxford-Cambridge Expressway, in contrast to the 01235 422600 www.southoxon.gov.uk previous Conservative administration’s support for it. While it has now been ‘paused’, local campaigners and Citizens Advice – 0808 278 7907 experts are concerned that road projects promoted by the BIVC (Berinsfield) - 01865 343044 County Council, including a possible flyover at Golden Balls roundabout, may amount to part of a ‘stealth’ Age UK Oxfordshire: 01865 411 288 Expressway section joining the A34 to the M40. Cllr Robin Bennett in Garsington in 2019 Cllr Robin says: “We should invest in public transport, looking at possible Expressway routes Oxfordshire County Council Priority cycling and walking, fixing existing roads rather than Support for Vulnerable residents: building more of them.” 01865 897820 or Green Councillors make a difference [email protected] Elect hard-working District Councillor Robin Bennett to serve Oxfordshire Mind: 01865247788 you on Oxfordshire County Council. Greens and Lib Dems took www.oxfordshiremind.org.uk control of South Oxfordshire district council after the 2019 local elections, and challenged the unpopular Conservative local plan. Business support and information: Controversial minister Robert Jenrick stepped in and interfered www.svbs.co.uk with our local democracy – while Oxfordshire’s Conservative and Labour County councillors voted to take over the plan – but Cllr Robin continued to fight for improvements, including better policies on climate change, cycling and nature. -

THE PARISH of BERRICK SALOME Minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting Held on 22Nd May 2006 at the Berrick Salome Village Hall at 8.00 P.M

Signed …………………………………………………..…………….. (Berrick Salome Parish Council Chairman) THE PARISH OF BERRICK SALOME Minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting held on 22nd May 2006 at the Berrick Salome Village Hall at 8.00 p.m. 1. Apologies for absence None were received. 2. Minutes of the last meeting The minutes of the last Annual Parish Meeting held on 6th June 2005 were read by John Radice, and approved and signed by Sarah Hicks. 3. Matters arising Item 11: Chris Cussens informed the Meeting that the Millstream Day Centre was in need of a new cooker, costing around £2,000. 4. The Annual Report of Parish Council This was presented by the chairman, Sarah Hicks. The main focus of Parish Council activities this year has again been on planning issues. 13 planning applications have been presented this year and of these 6 were granted, 4 refused and 3 withdrawn. One of those granted was for the Home Sweet Home to build a first floor extension, which will allow them to offer Bed & Breakfast accommodation. The most controversial planning application we saw was for Roke Farm. The Parish Council called an extra meeting to discuss one version of the plans, and that was attended by many local residents as well as the architect and applicants. On that occasion we recommended that the plan be refused, they were then withdrawn and replaced with a slightly reduced version. This time, the plans split the Council and by a majority vote we recommended them for approval. The SODC planning committee then refused the application by unanimous vote. -

Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035

CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version 1 Cover picture: Riverside Meadows Local Green Space (Policy CRP 6) 2 CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 6 • The Parish Vision • Objectives of the Plan 2. The neighbourhood area 10 3. Planning policy context 21 4. Community views 24 5. Land use planning policies 27 • Policy CRP1: Village boundaries and infill development • Policy CRP2: Housing mix and tenure • Policy CRP3: Land at Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford • Policy CRP4: Conservation of the environment • Policy CRP5: Protection and enhancement of ecology and biodiversity • Policy CRP6: Green spaces 6. Implementation 42 Crowmarsh Parish Council January 2021 3 List of Figures 1. Designated area of Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2. Schematic cross-section of groundwater flow system through Crowmarsh Gifford 3. Location of spring line and main springs 4. Environment Agency Flood risk map 5. Chilterns AONB showing also the Ridgeway National Trail 6. Natural England Agricultural Land Classification 7. Listed buildings in and around Crowmarsh Parish 8. Crowmarsh Gifford and the Areas of Natural Outstanding Beauty 9. Policies Map 9A. Inset Map A Crowmarsh Gifford 9B. Insert Map B Mongewell 9C. Insert Map C North Stoke 4 List of Appendices* 1. Baseline Report 2. Environment and Heritage Supporting Evidence 3. Housing Needs Assessment 4. Landscape Survey and Impact Assessment 5. Site Assessment Crowmarsh Gifford 6. Strategic Environment Assessment 7. Consultation Statement 8. Compliance Statement * Issued as a set of eight separate documents to accompany the Plan 5 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Neighbourhood Plans are a recently introduced planning document subsequent to the Localism Act, which came into force in April 2012. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Timetables: South Oxfordshire Bus Services

Drayton St Leonard - Appleford - Abingdon 46 Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays Drayton St Leonard Memorial 10.00 Abingdon Stratton Way 12.55 Berinsfield Interchange west 10.05 Abingdon Bridge Street 12.56 Burcot Chequers 10.06 Culham The Glebe 13.01 Clifton Hampden Post Office 10.09 Appleford Carpenters Arms 13.06 Long Wittenham Plough 10.14 Long Wittenham Plough 13.15 Appleford Carpenters Arms 10.20 Clifton Hampden Post Office 13.20 Culham The Glebe 10.25 Burcot Chequers 13.23 Abingdon War Memorial 10.33 Berinsfield Interchange east 13.25 Abingdon Stratton Way 10.35 Drayton St Leonard Memorial 13.30 ENTIRE SERVICE UNDER REVIEW Oxfordshire County Council Didcot Town services 91/92/93 Mondays to Saturdays 93 Broadway - West Didcot - Broadway Broadway Market Place ~~ 10.00 11.00 12.00 13.00 14.00 Meadow Way 09.05 10.05 11.05 12.05 13.05 14.05 Didcot Hospital 09.07 10.07 11.07 12.07 13.07 14.07 Freeman Road 09.10 10.10 11.10 12.10 13.10 14.10 Broadway Market Place 09.15 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Broadway, Park Road, Portway, Meadow Way, Norreys Road, Drake Avenue, Wantage Road, Slade Road, Freeman Road, Brasenose Road, Foxhall Road, Broadway 91 Broadway - Parkway - Ladygrove - The Oval - Broadway Broadway Market Place 09.15 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 Orchard Centre 09.17 10.17 11.17 12.17 13.17 14.17 Didcot Parkway 09.21 10.21 11.21 12.21 13.21 14.21 Ladygrove Trent Road 09.25 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 Ladygrove Avon Way 09.29 10.29 11.29 12.29 13.29 14.29 The Oval 09.33 10.33 11.33 12.33 13.33 14.33 Didcot Parkway 09.37 -

Guide to Accommodation Near UKCEH, Wallingford Site

Guide to accommodation near UKCEH, Wallingford site UKCEH provides this guide to guests at our Getting there by public transport: Wallingford site, who wish to stay overnight to attend Thames Travel operate a frequent bus service (X39/X40) between Oxford and events, conferences, workshops or training courses. Reading. This stops near to UKCEH Wallingford site in Crowmarsh Gifford. (www.thames-travel. co.uk/routes/x38x39x40). When travelling from Oxford, alight Our full postal address is: at Crowmarsh Gifford, opp. Crowmarsh Church (on The Street) and walk about 7 UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Maclean mins to UKCEH Wallingford site. Building, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford, When travelling from Reading, use the bus stop opposite Crowmarsh Gifford Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BB Village Hall (on Benson Lane) in Crowmarsh Gifford and walk about 4 mins to UKCEH Wallingford. You can find directions to UKCEH, Wallingford site here: There is also the X2 from Didcot to Wallingford (about every 30 minutes Mon-Sat www.ceh.ac.uk/wallingford and hourly on Sundays.) This requires a slightly longer walk (approx. 20min) from last updated: 28/11/2019 Wallingford town centre (www.thames-travel.co.uk/routes/x2). Recommend use of travel planner: www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk No. of Name Price Range Distance to Address and Contact Details Travel Options to UKCEH Nearest bus stop rooms UKCEH Wallingford and Crowmarsh Gifford The George Hotel £71 - £363 39 0.9 mile High Street, Wallingford, Oxfordshire Thames Travel Bus 136 towards Wallingford, (~20 min walk) OX10 OBS RAF Benson or X39/X40 towards Market Place, Stop Tel: +44 (0)1491 836665 Oxford. -

Unit 6, Crowmarsh Battle Barns, Preston Crowmarsh, Wallingford OX10 6SL Unit 6, Crowmarsh Battle Barns, Preston Crowmarsh, Wallingford, OX10 6SL £8,600 Pa

Unit 6, Crowmarsh Battle Barns, Preston Crowmarsh, Wallingford OX10 6SL Unit 6, Crowmarsh Battle Barns, Preston Crowmarsh, Wallingford, OX10 6SL £8,600 pa Unit 6 Crowmarsh Battle Barns forms part of the prestigious and award winning premises TERMS converted from beautiful 300 year old Grade II Listed timber frame barns which now offer The premises are available for occupation from adaptable office suites in rural surroundings close to local facilities. The unit measures 609 sq ft February 2015 on a full repairing and insuring (57 sq m) and includes an internal glass partitioned meeting room/office. basis for B1(a) office use. LOCATION (all distances are approximate) RENT The unit is available at a rent of £8,600 pa. The premises are situated on the Crowmarsh Battle Barns complex in the village of Preston Crowmarsh off the A4074 between Benson and Wallingford which provide extensive local services. SERVICE CHARGES The site has excellent access to: CROWMARSH In addition to the rent the Tenant will pay to the BATTLE Landlord a service charge to cover property BARNS Wallingford town centre (2 miles) London - West (45 miles) insurance, maintenance, services in communal Benson village (1 mile) M40 J 6 (10 miles) areas and landscape maintenance. Fast broadband connection is available on a separate Central Oxford (12 miles) Theale - M4 J 12 (15 miles) contract. Reading (14 miles) The nearest mainline railway stations are Cholsey Henley-on-Thames (12 miles) (4 miles) & Didcot Parkway (9 miles) BUSINESS RATES The rateable value for 2014/2015 is £8,600 pa. MAP OR PLAN The charging authority is South Oxfordshire District FEATURES Council. -

Situation of Polling Stations Police and Crime Commissioner Election

Police and Crime Commissioner Election Situation of polling stations Police area name: Thames Valley Voting area name: South Oxfordshire No. of polling Situation of polling station Description of persons entitled station to vote S1 Benson Youth Hall, Oxford Road, Benson LAA-1, LAA-1647/1 S2 Benson Youth Hall, Oxford Road, Benson LAA-7, LAA-3320 S3 Crowmarsh Gifford Village Hall, 6 Benson Lane, LAB1-1, LAB1-1020 Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford S4 North Stoke Village Hall, The Street, North LAB2-1, LAB2-314 Stoke S5 Ewelme Watercress Centre, The Street, LAC-1, LAC-710 Ewelme, Wallingford S6 St Laurence Hall, Thame Road, Warborough, LAD-1, LAD-772 Wallingford S7 Berinsfield Church Hall, Wimblestraw Road, LBA-1, LBA-1958 Berinsfield S8 Dorchester Village Hall, 7 Queen Street, LBB-1, LBB-844 Dorchester, Oxon S9 Drayton St Leonard Village Hall, Ford Lane, LBC-1, LBC-219 Drayton St Leonard S10 Berrick and Roke Village Hall, Cow Pool, LCA-1, LCA-272 Berrick Salome S10A Berrick and Roke Village Hall, Cow Pool, LCD-1, LCD-86 Berrick Salome S11 Brightwell Baldwin Village Hall, Brightwell LCB-1, LCB-159 Baldwin, Watlington, Oxon S12 Chalgrove Village Hall, Baronshurst Drive, LCC-1, LCC-1081 Chalgrove, Oxford S13 Chalgrove Village Hall, Baronshurst Drive, LCC-1082, LCC-2208 Chalgrove, Oxford S14 Kingston Blount Village Hall, Bakers Piece, LDA-1 to LDA-671 Kingston Blount S14 Kingston Blount Village Hall, Bakers Piece, LDC-1 to LDC-98 Kingston Blount S15 Chinnor Village Hall, Chinnor, Church Road, LDB-1971 to LDB-3826 Chinnor S16 Chinnor Village Hall, -

A Later Bronze Age Trackway Atsix Acres, Thame Road, Warborough

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S Bronze Age field boundaries at Six Acres, Thame Road, Warborough, Oxfordshire Archaeological Excavation by David Sanchez and Maisie Foster Site Code: TRW16/134 (SU 5985 9338) A Later Bronze Age trackway at Six Acres, Thame Road, Warborough, Oxfordshire An Archaeological Excavation For Rectory Homes by David Sanchez and Maisie Foster Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code TRW16/134 December 2019 Summary Site name: Six Acres, Thame Road, Warborough, Oxfordshire Grid reference: SU 5985 9338 Site activity: Excavation Date and duration of project: 9th - 17th October 2019 Project coordinator: Steve Ford Site supervisor: David Sanchez Site code: TRW 16/134 Area of site: c. 0.08ha Summary of results: The archaeological excavations revealed a number of recut ditches and gullies forming a trackway of Late Bronze Age - early Iron Age date. Although dating evidence was not plentiful, it was all reasonably consistent. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited at Oxfordshire Museums Service in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. All TVAS unpublished fieldwork reports are available on our website: www.tvas.co.uk/reports/reports.asp. Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford 16.12.19 Steve Preston 13.12.19 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. (0118) 926 0552; email [email protected]; website: www.tvas.co.uk A Later Bronze Age trackway at Six Acres, Thame Road, Warborough, Oxfordshire An Archaeological Excavation by David Sanchez and Maisie Foster with contributions by Ceri Falys, Joanna Pine, Richard Tabor and Steve Ford Report 16/134d Introduction An archaeological excavation was carried out by Thames Valley Archaeological Services over three targeted areas on an irregular parcel of land situated centrally within the village of Warborough, Oxfordshire (SU 5985 9338). -

The Doctors House

The Doctors House The Doctors House LITTLE MILTON, OXFORDSHIRE OX44 7PU A handsome village house with studio/home office and beautiful landscaped gardens with tennis court and swimming pool Oxford City Centre: 9 miles • M40 (Junction7) 2 miles • London (Paddington) approximately 40 minutes from Didcot, London (Marylebone) approximately 45 minutes from Haddenham. (All distances and times are approximate) • Entrance hall, drawing room, dining room, study, kitchen/breakfast room, conservatory, cloakroom, laundry/boot room, 4 bedrooms (2 en-suite), shower room, 2 loft rooms. • Attached annexe: sitting room, kitchen, bathroom, mezzanine bedroom. • Detached double garage with studio room above (25’1 x 17’5”) • Mature landscaped gardens with large pond, tennis court and swimming pool. • Garden stores, greenhouse. In all about 1.72 acres Savills Summertown 256 Banbury Road, Summertown, Oxford OX2 7DE [email protected] 01865 339700 DIRECTIONS From London take the M40, exit at junction 7. Proceed left onto the A329 pass signs to Great Haseley and Great Milton and proceed into the village of Little Milton. Continue into the village where The Doctors House will be found on the left opposite The Lamb pub. From Oxford take the B480 Cowley to Watlington road. Continue into the village of Stadhampton and at the mini roundabout, cross straight over (on the A329) towards Little Milton and the M40. Continue into Little Milton, where The Doctors House will be found on the right opposite The Lamb pub and just before the right hand bend. SITUATION Little Milton is a popular village well situated not only for Oxford City Centre, but also for London, with Junction 7 of the M40 only 2 miles, and fast trains from Haddenham (11 miles) to London (Marylebone) and Didcot (13 miles) to London (Paddington). -

South Oxfordshire Zone Kidlington Combined Ticket Or a A40 Boundary Points Cityzone EXTRA Ticket

Woodstock Oxford Travel to Woodstock is A4260 Airport available on a cityzone & A44 South Oxfordshire Zone Kidlington combined ticket or a A40 Boundary points cityzone EXTRA ticket. Travel beyond these points requires a cityzone or SmartZone product. A Dual zone products are available. 3 4 Thornhill B 40 20 A40 Park&Ride 44 A4 Certain journeys only l B Bot ey Rd 4 B Wheatley 4 4 Botley 9 0 5 1 ©P1ndar 7 This area4 is not©P 1coveredndar by ©P1ndar 2 C 4 o w 1 le 4 Matthew y A the standalone South R Oxfordshire OXF A Arnold School 3 o ad Cowley (Schooldays Only) 4 LGW Cumnor product. UnipartUnipart House House O xfo LHR Templars rd Kenilworth Road W R Square a d tli Hinksey4 H4ill ng 0 to 2 Henwood n Garsington 4 R A d A34 11 Wootton Sandford-on-Thames C h i s 34 e Sugworth l A h X3 Crescent H a il m d l A4 p to oa 0 R 7 n 4 Radley X38 4 Stadhampton d M40 r o f X2 45 B 35 X39 480 Chinnor A409 Ox 9 00 Berinsfield B4 X40 B Kingston Blount 5 A 415 48 0 ST1 0 42 Marcham H A ig Chalgrove A41 Abingdon h S Lewknor 7 Burcot t LGW LHR Faringdon Culham Science 95B 9 0 X32 45 Pyrton 0 7 Centre 67 1 O 80 B4 to Heathrow/Gatwick 8 0 x B4 0 4 4 Clifton fo Cuxham 45 3 B rd (not included) B A Culham Pa Sta Hampden R rk n Rd 95 o R fo a 11 d rd R w X2 33 Dorchester d d A o Berwick 67C 41 Long 9 B Warborough Shellingford 7 Sutton Wittenham Salome 00 Stanford in Drayton B4 0 East Hanney Courtenay 2 67 Watlington 4 The Vale X36 Little A Milton Wittenham 67C Milton A4 F 0 7 B a Park 4 4 r Shillingford 136 i 8 n 8 g 3 0 3 Steventon d Ewelme o A Benson n 33 R -

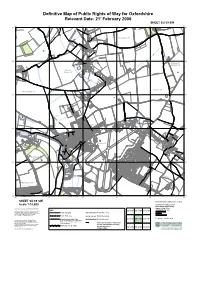

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 69 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 69 SW 307/9a 60 392/15b 61 62 63 64 65 307/9b 4200 7800 0006 0004 0003 2400 6900 6100 307/9a 95 Chy 95 0 Lonesome Farm Whitehouse Farm A 329 A 307/15 39 Kennels 2/15b 307/1 Whitehouse Lodge 2191 307/9b Drain 307/8 Ponds 204/32 8785 307/15 0082 1380 140/3 140/3 Pond Drain 307/10 204/33 204/13 Pond 5375 Drain 0075 9673 Drain Pond 9272 A 329 1972 127/9 Newington CP Pond Manor Farm Spring Spring 307/9a Pond 127/9Issues 0057 Pond RUMBOLDS LANE (Track) Myrtle Cottage Collects 6954 6454 127/8 Drain 6751 Drain 5652 Pond 307/9b Northfield Drain Mokes Corner En-dah-win Stonewold 127/7 204/33 Pond Priory The Chase Cottage Dunelm 0944 Drain Meadowcroft 0042 127/4 The Innocents Deane's Hurst 0041 Barosan Drain 204/33 Rosslyn Pond The Orchard 3535 Pond 127/7 Pond Drain 9235 127/4 Warburton Church Cottage Pond Tanner PO Cottage 3430 PH The Chequers Ivyhouse Farm Drain Drain 3728 Inn Drain Pond Pond Upper Berrick St Helen's Church 127/5 Drain 127/4 1522 0022 The Malt House 127/6 392/15b Pond Drain 1614 127/6 Pond The Old Post Office Drain Trecorn House Ponds Drain Issues Shambles 127/4 Drain 392/15a Two Jays 0001 Hollantide Cottage 0005 1500 0001 3600 3600 5600 1500 3500 204/13 0005 Berrick House 0042 0001 94 Caer Urfa 94 Parsonage Farm Lower Berrick Farm 127/5 Parsonage Cottage BERRICK Drain Stonehaven Drain Brightwell Stable 0090 Cottage SALOME Drain Cases Co Grace's Farm urt Allnuts Pond Nurseries Baldwin CP Brookfield Drain Triad Lothlorien Pond