THE US-ISLAMIC MEDIA CHALLENGE: Twenty Versions of One Event— Similarities and Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

§3008. Ordinances Relating to Cable Television Systems §3008

MRS Title 30-A, §3008. ORDINANCES RELATING TO CABLE TELEVISION SYSTEMS §3008. Ordinances relating to cable television systems 1. State policy. It is the policy of this State, with respect to cable television systems: A. To affirm the importance of municipal control of franchising and regulation in order to ensure that the needs and interests of local citizens are adequately met; [PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. A, §2 (NEW); PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. C, §106 (NEW); PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §§8, 10 (AMD).] B. That each municipality, when acting to displace competition with regulation of cable television systems, shall proceed according to the judgment of the municipal officers as to the type and degree of regulatory activity considered to be in the best interests of its citizens; [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (AMD).] C. To provide adequate statutory authority to municipalities to make franchising and regulatory decisions to implement this policy and to avoid the costs and uncertainty of lawsuits challenging that authority; and [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (AMD).] D. To ensure that all cable television operators receive the same treatment with respect to franchising and regulatory processes and to encourage new providers to provide competitive pressure on the pricing of such services. [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (NEW).] [PL 2007, c. 548, §1 (AMD).] 1-A. Definitions. For purposes of this section, unless the context otherwise indicates, the following terms have the following meanings: A. "Cable system operator" has the same meaning as "cable operator," as that term is defined in 47 United States Code, Section 522(5), as in effect on January 1, 2008; [PL 2007, c. -

Download (1MB)

Abrar, Muhammad (2012) Enforcement and regulation in relation to TV broadcasting in Pakistan. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3771/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Enforcement and Regulation in Relation to TV Broadcasting in Pakistan Muhammad Abrar Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow November 2012 Abstract Abstract In 2002, private broadcasters started their own TV transmissions after the creation of the Pakistan Electronic Media Authority. This thesis seeks to identify the challenges to the Pakistan public and private electronic media sectors in terms of enforcement. Despite its importance and growth, there is a lack of research on the enforcement and regulatory supervision of the electronic media sector in Pakistan. This study examines the sector and identifies the action required to improve the current situation. To this end, it focuses on five aspects: (i) Institutional arrangements: institutions play a key role in regulating the system properly. (ii) Legislative and regulatory arrangements: legislation enables the electronic media system to run smoothly. -

National Responses to International Satellite Television

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 363 261 IR 016 165 AUTHOR Jayakar, Krishna P. TITLE National Responses to International Satellite Television. PUB DATE Apr 93 NOTE 20p.; Paper presented at the Arinual Convention of the Broadcast Education Association (Las Vegas, NV, April 16-18, 1993). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advertising; Audience Response; *Broadcast Television; Business; Cable Television; Case Studies; *Communications Satellites; Foreign Countries; *Government Role; *International Law; Legislation; Problems IDENTIFIERS *Asia; Government Regulation; India; *International Broadcasting ABSTRACT Star TV, the first international satellite broadcast system in Asia, has had a profound effect on national broadcasting systems, most of which are rigidly controlled, state owned monopoly organizations. The purpose of this paper was to study theresponse of national governments, media industries, and the general publicto this multichannel direct broadcast service. India is usedas a case study because it is generally representative of Asian national broadcast environments and has been specially targeted asa potential market for Star TV's services. Public response to the service has been enthusiastic. Industry has mainly viewed itas a short-term, money-making opportunity. Governments, however, perceive Star TVas a commercial/economic enterprise, and their policyresponses have also been governed by this perception. Efforts made by governmentsso far have been either to strengthen domestic broadcast systems,or to control cable systems that function as carriers for satellite signals. No attempt has been made to apply the provisions of international law which guarantee nations the right of prior consultation and consent to satellite broadcastingor to evolve supranational regional regulatory frameworks. -

Cable-Satellite Networks: Structures and Problems

Catholic University Law Review Volume 24 Issue 4 Summer 1975 Article 3 1975 Cable-Satellite Networks: Structures and Problems George H. Shapiro Gary M. Epstein Ronald A. Cass Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation George H. Shapiro, Gary M. Epstein & Ronald A. Cass, Cable-Satellite Networks: Structures and Problems, 24 Cath. U. L. Rev. 692 (1975). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol24/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CABLE-SATELLITE NETWORKS: STRUCTURES AND PROBLEMSt George H. Shapiro* Gary M. Epstein** Ronald A. Cass** * Unlike the broadcast television industry, in which programming is domi- nated by three giant networks, the cable television industry is quite fragment- ed. Most cable television systems are small operations, and although a few large cable organizations own numerous systems, the individual cable sys- tems they operate typically are dispersed over wide geographic areas and are not interconnected. Thus, compared to television broadcast stations, which, even if not affiliated with a network, generally reach large viewing audi- ences, cable systems constitute small economic units.' The programming "originated" by cable systems-that is, programming not obtained from television broadcasts-reflects the industry's economic structure. Small cable systems are not able individually to procure programming with the same mass appeal as that of broadcast networks or individual broadcast stations, 2 so originations presently are locally oriented and seldom sophisticated. -

Must-Carry Rules, and Access to Free-DTT

Access to TV platforms: must-carry rules, and access to free-DTT European Audiovisual Observatory for the European Commission - DG COMM Deirdre Kevin and Agnes Schneeberger European Audiovisual Observatory December 2015 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction and context of study 7 Executive Summary 9 1 Must-carry 14 1.1 Universal Services Directive 14 1.2 Platforms referred to in must-carry rules 16 1.3 Must-carry channels and services 19 1.4 Other content access rules 28 1.5 Issues of cost in relation to must-carry 30 2 Digital Terrestrial Television 34 2.1 DTT licensing and obstacles to access 34 2.2 Public service broadcasters MUXs 37 2.3 Must-carry rules and digital terrestrial television 37 2.4 DTT across Europe 38 2.5 Channels on Free DTT services 45 Recent legal developments 50 Country Reports 52 3 AL - ALBANIA 53 3.1 Must-carry rules 53 3.2 Other access rules 54 3.3 DTT networks and platform operators 54 3.4 Summary and conclusion 54 4 AT – AUSTRIA 55 4.1 Must-carry rules 55 4.2 Other access rules 58 4.3 Access to free DTT 59 4.4 Conclusion and summary 60 5 BA – BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 61 5.1 Must-carry rules 61 5.2 Other access rules 62 5.3 DTT development 62 5.4 Summary and conclusion 62 6 BE – BELGIUM 63 6.1 Must-carry rules 63 6.2 Other access rules 70 6.3 Access to free DTT 72 6.4 Conclusion and summary 73 7 BG – BULGARIA 75 2 | Page 7.1 Must-carry rules 75 7.2 Must offer 75 7.3 Access to free DTT 76 7.4 Summary and conclusion 76 8 CH – SWITZERLAND 77 8.1 Must-carry rules 77 8.2 Other access rules 79 8.3 Access to free DTT -

Office of Cable Television OCT (CT)

Office of Cable Television OCT (CT) MISSION The mission of the Office of Cable Television (OCT) is to: (1) regulate the provision of “cable service” in the District of Columbia (as that term is defined by the District’s cable television laws); (2) protect and advance the cable television-related interests of the District and its residents: and (3) produce and cablecast live and recorded video and other programming by way of the District’s public, educational and government (PEG) cable channels. SUMMARY OF SERVICES OCT: (1) regulates the provision of cable television services by the District’s cable television franchisees; (2) manages the District’s two municipal government cable channels (TV-13, TV-16); and (3) manages the District Knowledge Network (DKN) (formerly “District Schools Television” (DSTV)). TV-13 provides gavel-to-gavel coverage of the activities of the Council of the District of Columbia. TV-16 provides information regarding the many programs, services and opportunities made available by the Government of the District of Columbia. DKN (i.e., the District’s re-formatted schools / educational cable channel) is designed to provide residents with superior quality educational programming that not only fosters and encourages student learning and achievement, but that also provides to our community life- long learning opportunities. Via these channels, OCT provides to District residents immediate and comprehensive access to the activities and processes of their government. AGENCY OBJECTIVES 1. Increase the public’s access to their local government through its municipal television channels. 2. Protect and advance the cable television-related interests of District residents. ACCOMPLISHMENTS OCT successfully negotiated a new cable television franchise agreement with Verizon (allowing it to become the District’s third cable television service provider). -

Pay TV Market Overview Annex 8 to Pay TV Market Investigation Consultation

Pay TV market overview Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation Publication date: 18 December 2007 Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation - pay TV market overview Contents Section Page 1 Introduction 1 2 History of multi-channel television in the UK 2 3 Television offerings available in the UK 22 4 Technology overview 60 Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation - pay TV market overview Section 1 1 Introduction 1.1 The aim of this annex is to provide an overview of the digital TV services available to UK consumers, with the main focus on pay TV services. 1.2 Section 2 describes the UK pay TV landscape, including the current environment and its historical development. It also sets out the supply chain and revenue flows in the chain. 1.3 Section 3 sets out detailed information about the main retail services provided over the UK’s TV platforms. This part examines each platform / retail provider in a similar way and includes information on: • platform coverage and geographical limitations; • subscription numbers (if publicly available) by platform and TV package; • the carriage of TV channels owned by the platform operators and rival platforms; • the availability of video on demand (VoD), digital video recorder (DVR), high definition (HD) and interactive services; • the availability of other communications services such as broadband, fixed line and mobile telephony services. 1.4 Section 4 provides an overview of relevant technologies and likely future developments. 1 Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation - pay TV market overview Section 2 2 History of multi-channel television in the UK Introduction 2.1 Television in the UK is distributed using four main distribution technologies, through which a number of companies provide free-to-air (FTA) and pay TV services to consumers: • Terrestrial television is distributed in both analogue and digital formats. -

Channel and Setup Guide

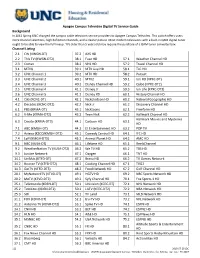

Apogee Campus Televideo Digital TV Service Guide Background In 2013 Spring UNC changed the campus cable television service providers to Apogee Campus Televideo. This switch offers users more channel selections, high definition channels, and a clearer picture. Most modern televisions with a built-in QAM digital tuner ought to be able to view the full lineup. TVs older than 5 years old may require the purchase of a QAM tuner converter box. Channel Listing 2.1 CW (KWGN-DT) 37.2 AXS HD 2.2 This TV (KWGN-DT2) 38.1 Fuse HD 57.1 Weather Channel HD 2.3 Comet 38.2 VH1 HD 57.2 Travel Channel HD 3.1 MTVU 39.1 MTV Live HD 58.1 TLC HD 3.2 UNC Channel 1 39.2 MTV HD 58.2 Pursuit 3.3 UNC Channel 2 40.1 MTV2 59.1 Ion HD (KPXC-DT) 3.4 UNC Channel 3 40.2 Disney Channel HD 59.2 Qubo (KPXC-DT2) 3.5 UNC Channel 4 41.1 Disney Jr 59.3 Ion Life (KPXC-DT3) 3.6 UNC Channel 5 41.2 Disney XD 60.1 History Channel HD 4.1 CBS (KCNC-DT) 42.1 Nickelodeon HD 60.2 National Geographic HD 4.2 Decades (KCNC-DT2) 42.2 Nick Jr 61.2 Discovery Channel HD 6.1 PBS (KRMA-DT) 43.1 Nicktoons 62.1 Freeform HD 6.2 V-Me (KRMA-DT2) 43.2 Teen Nick 62.2 Hallmark Channel HD Hallmark Movies and Mysteries 6.3 Create (KRMA-DT3) 44.1 Cartoon HD 63.1 HD 7.1 ABC (KMGH-DT) 44.2 E! Entertainment HD 63.2 POP TV 7.2 Azteca (KZCO/KMGH-DT2) 45.1 Comedy Central HD 64.1 IFC HD 7.4 Laff (KMGH-DT3) 45.2 Animal Planet HD 64.2 AMC HD 9.1 NBC (KUSA-DT) 46.1 Lifetime HD 65.1 ReelzChannel 9.2 WeatherNation TV (KUSA-DT2) 46.2 We TV HD 65.2 TBS HD 9.3 Justice Network 47.1 Oxygen 66.1 TNT HD 14.1 UniMás (KTFD-DT) -

Wealth Effects of Acquisitions and Divestitures in the Entertainment Industry

Diversification or Focus? Wealth Effects of Acquisitions & Divestitures in the Entertainment Industry by Kenneth Low An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2013 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Kose John Faculty Adviser Thesis Adviser 1 ABSTRACT The US entertainment industry is dominated by media conglomerates that have diversified their media operations through many years of corporate acquisitions. However, past research indicates that firms which acquire highly-related businesses tend to outperform firms which acquire poorly-related businesses, thereby suggesting that firms benefit from focused operations. In addition, M&A trends in the entertainment industry over the last ten years indicate that firms have moved away from poorly-related acquisitions that diversify their business to highly-related acquisitions that focus their operations, further fueling the discussion of the influence of business relatedness on firm performance. Should entertainment firms pursue diversification or focus? This thesis attempts to identify the optimal business development and acquisition strategy for entertainment firms today by analyzing the influence of business relatedness on wealth effects of corporate acquisitions and divestitures in the industry. The study finds that, in the entertainment industry, the market tends to favor highly-related acquisitions over poorly- related acquisitions and divestitures of poorly-related assets over divestitures of highly- related assets. Taken together, these findings suggest that the ideal business development strategy for entertainment firms today is one that pursues operational focus. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Professor Kose John, my thesis advisor, for his extremely valuable advice and support during the research and writing process of this thesis. -

28 Satellite Television and Radio

28 Satellite Television And Radio The governmenT played a major role in the development of the satellite industry, as, over the course of several decades, NASA and the Defense Department invested tens of billions of dollars to develop the technology for satel- lites.1 Congress also intervened mightily in 1992 by enacting the “program access” law that requires cable operators to make their programming available to their satellite competitors on non-discriminatory terms.2 The FCC in 2007 extended those rules for five additional years.3 Set Asides The Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992 required the FCC to impose on satellite TV, also known as direct broadcast satellite (DBS), “public interest or other requirements for providing video program- ming.”4 Congress decreed that satellite TV operators must reserve between 4 and 7 percent of their channel capacity to carry “noncommercial programming of an educational or informational nature” at reduced rates.5 Eligibility for this preferential access was limited to “any qualified noncommercial educational television station, other public telecom- munications entities, and public or private educational institutions.”6 With the flexibility to choose a noncommercial set aside of between 4 and 7 percent, in 1998 the Commission chose 4 percent on the grounds that the satellite industry was in its infancy and a larger set-aside requirement might “hinder DBS in developing as a viable competitor.”7 Eligibility for set-aside channels is limited to nonprofit organizations that provide “noncommercial program- ming,” defined largely by the absence of advertising.8 The Commission envisioned that a wide variety of programming would be made available to DBS subscribers over the set-aside capacity, including distance learning, children’s education- al programming, and medical, historical, and scientific programming.9 However, the satellite operators now reject most applicants because they already have hit the 4 percent mark. -

Television and Cable Network Programming the Company's Television Operations Primarily Consist of FOX, Mynetworktv and the 27

Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations (continued) Television and Cable Network Programming The Company’s television operations primarily consist of FOX, MyNetworkTV and the 27 television stations owned by the Company. The television operations derive revenues primarily from the sale of advertising and to a lesser extent retransmission compensation. Adverse changes in general market conditions for advertising may affect revenues. The U.S. television broadcast environment is highly competitive and the primary methods of competition are the development and acquisition of popular programming. Program success is measured by ratings, which are an indication of market acceptance, with the top rated programs commanding the highest advertising prices. FOX is a broadcast network and MyNetworkTV is a programming distribution service, airing original and off-network programming. FOX and MyNetworkTV compete with broadcast networks, such as ABC, CBS, NBC and The CW, independent television stations, cable and DBS program services, as well as other media, including DVDs, Blu-rays, video games, print and the Internet for audiences, programming and, in the case of FOX, advertising revenues. In addition, FOX and MyNetworkTV compete with the other broadcast networks and other programming distribution services to secure affiliations with independently owned television stations in markets across the country. Retransmission consent rules provide a mechanism for the television stations owned by the Company to seek and obtain payment from multi- channel video programming distributors who carry broadcasters’ signals. Retransmission compensation consists of per subscriber-based compensatory fees paid to the Company from cable and satellite distribution systems as well as a portion of the retransmission revenue the affiliates generate for their retransmission of FOX and MyNetworkTV.