GENDERED SPACES Craftswomen's Stories of Self-Employment In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizen Forum of WODC

DATA WODC SINCE INCEPTION TILL 05.08.2016 Project Released Sl No ID DISTRICT Executing Agency Name of the Project Amount Year Completion of Bauribandha Check Dam & Retaining Wall B.D.O., at Angapada, Angapada G.P. of 1 20350 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bridge Between Budiabahal to Majurkachheni, B.D.O., Kadalimunda G.P. of 2 20238 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Constn. of Main Building Ambapal Homeopathy B.D.O., Dispensary, Ambapal G. P. of 3 20345 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Completion of Addl. Class Room of Lunahandi High School Building, Lunahandi 4 19664 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. G.P. of Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Constn. of Gudighara Bhagabat Tungi at Tentheipali, Kudagaon G.P. of 5 19264 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Constn. of Kothaghara at Tentheipali, Kudagaon G.P. of 6 19265 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Completion of Building and Water Supply to Radhakrishna High School, B.D.O., Pursmala, Urukula G.P. of 7 19020 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 700000 2014-2015 Completion of Pitabaligorada B.D.O., Bridge, Urukula G.P. of 8 19019 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 900000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bridge at Ghaginallah in between Ghanpur Serenda Road, B.D.O., Urukula G.P. of Kishorenagar 9 19018 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Block 1000000 2014-2015 Completion of Kalyan Mandap at Routpada, Kandhapada G.P. 10 19656 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. of Athmallik Block 200000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bhoga Mandap inside Maheswari Temple of 11 19659 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. -

Goddess Kali Temples at Srikshetra

Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669 Goddess Kali Temples at Srikshetra Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra Introduction construction of temples in all parts of the kshetra. Srikshetra popularly known as Puri, is situated Before the British occupation of Odisha, this (Latitude 190 47m 55s North and Longitude 850 kshetra was the political headquarters of the 49m 5s East) on the shore of the Bay of Bengal in eastern part of Odisha. Prior to the advent of the state of Odisha.1 It is located about 59 kms Vaishnavism, the kshetra was a Sakta pitha and it to the south-east can be substantiated of Bhubaneswar. both by the literary The place of texts containing the Srikshetra is well- list of Sakta pithas in known for its Tantric texts and historic antiquities archaeological and religious evidences. Kali or sanctuaries in Mahakali, the first India. The term Mahavidya, is the ‘Sri’ before most popular deity kshetra denoting in India as well as either goddess Odisha. The present Lakshmi or simply form of Kali beauty.2 On the basis of Puranic tradition, Lakshmi worship is mainly based on the Kali Tantra and is the mistress of the kshetra and hence the place Tantrasara. Goddess Kali is being worshipped (Puri town) often called as Srikshetra. A survey by local people of Puri town in different names / of the extant temples of the Srikshetra reveals that forms like Bedhakali, Dakshinakali, Shyamakali, there was brisk architectural activities started from Smasana Kali, Gachhakali, etc. Of all the forms the Somavamsi period (10th century A.D.) and of Kali, Dakshina Kali is very popular and is also completed in the Maratha period of Odishan known as Adyakali.3 For the spread of worship history. -

Practical Examiner List AITT March 2021 Annexure-I Page 1 of 66

Practical Examiner List AITT March 2021 Annexure-I Number of CONTACT District ITI Name ITI Code Examiner EXAMINER NAME AND ADDRESS TRADE/BRANCH EMAIL ID NUMBER Allotted Saranga Mahanta, Gayatri itc mahanta.saranga@gmail. Electrician 2 ELECTRICIAN 9437147209 Kankadahada, Dhenkanal com Manabhanjan Nayak, T.O. nayakmanabhanjan92@g Electrician 7873275166 Ashirwad ITI, Mahidharpur, Angul mail.com Electronics 1 Mechanic Santosh Kumar Maharana,Sr Instructor Fitter [email protected] Fitter 2 Fitter 9337170041 OPJITS,Angul m Govt Industrial Training ANGUL GU21000531 Santanu Kumar Dehury, Maharishi ITC,Angul Fitter 9861453774 [email protected] Institute, Talcher Machinist 0 Mechanic (Motor 0 Vehicle) Turner 1 Hemanta Kumar Rout,Matrushakti ITC ( ATO Electrician ) hemantarout1977@gmail Wireman 1 Electrician 9937190924 At/Po Samal Barrage .com Via Talcher, Pin 759037 RAM NARAYAN HOTA, Sushree ITC Gandhamardan Electrician 1 ELECTRICIAN 7978596411 [email protected] Government Industrial GU21000507 Electronics Training Institute, 1 Bibartan Nayak, Govt. ITI, Bolangir Bibartan Nayak 7064033760 Bolangir Mechanic Balagopal Biswal (ATO-Fitter) Fitter Fitter [email protected] 1 Sulochna ITC,Puintala,Balangir 8249529940 Draughtsman 0 (Civil) Draughtsman 0 BOLANGIR (Mechanical) Electrician 1 P.K.SAHU,Sushree ITC ELECTRICIAN 9937494281 [email protected] Electronics Swayam Prava Sahoo,Gandhamardhan ITI, 1 Electronics 9438766657 Govt Industrial Training Mechanic Bolangir GU21000513 Institute, Bolangir Srinabash Sarangi (ATO-Fitter) Fitter Fitter [email protected] 1 Sulochna ITC,Puintala,Balangir 9668512451 Mechanic (Motor 0 Vehicle) 0 Page 1 of 66 BOLANGIR Govt Industrial Training GU21000513 Institute, Bolangir Practical Examiner List AITT March 2021 Annexure-I Number of CONTACT District ITI Name ITI Code Examiner EXAMINER NAME AND ADDRESS TRADE/BRANCH EMAIL ID NUMBER Allotted Wireman 0 Draughtsman 0 (Mechanical) Kamalakanta Andia A.T.O Electrician. -

Tourism Are Chilka Lake, Pipili, Chandrabhaga, Konark and Satapara

Tourist importance of some stations over Khurda Road Division PURI The majestic Jagannath Temple in Puri is a major pilgrimage destination for Hindus and is a part of the “Char Dham”pilgrimages.Puri is also famous for Ratha Yatra and other nearby places of interest in terms of tourism are Chilka Lake, Pipili, Chandrabhaga, Konark and Satapara Konark Sun Temple is a 13th-century Christian Era sun temple at Konark about 35 kilometres (22 mi) northeast from Puri on the coastline of Odisha, The temple is dedicated to the Hindu 'god Surya, what remains of the temple complex has the appearance of a 100-foot (30 m) high chariot with immense wheels and horses, all carved from stone. Temple is also called the Surya Devalaya, it is a classic illustration of the Odisha style ofHindu temple architecture.[1][6] Puri Sea Beach is a famous beach on the shore of Bay of Bengal, in the city of Puri, Odisha. Puri Beach offers clean sands and roaring seas with the main attraction being the stunning sunrise and sunset scenes. Puri Beach also has religious importance as devotees come here to take a dip after visiting the revered Jagannath Temple nearby... One of the sacred tourist destination of orissa, Sakhigopal is a village of historical importance which is situated 19 kms. north of Puri on the way to Bhubaneswar. It is the most famous spot of Odisha for cocoanut industry. It is one of the top calibrekrishna temple of the country. It is a saying that unless Sakhigopal is visited the piligrimage to Puri is not complete. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Identification and Validation of Leprosy Colonies in India: a Study Report

Identification and Validation of Leprosy Colonies in India: A Study Report Identification and Validation of Leprosy Colonies in India (A Study Report) March 2020 Sasakawa-India Leprosy Foundation IETE Building, II Floor 2, Lodhi Road, Institutional Area, New Delhi, 110003 www.silf.in End Discrimination, Spread Smile........... Page 1 Identification and Validation of Leprosy Colonies in India: A Study Report Table of Contents Sl. Description Pg. No. No. 1 Introduction 4 2 Objectives of the Study 5 3 Limitation of the Study 5 4 Methodology and Approach of the Study 5 4.1 Reaching Out the Major Stakeholders for Cooperation and Available Data 5 4.2 Source of Data 6 4.3 Scope of the Study 6 4.4 Study Method and Tool 6 4.5 Study Variables 6 4.6 Data Collection 7 5 Study Findings 8 5.1 Number of Colonies in the Country 8 5.2 Number of Families and Population Size of the Colonies 21 6 Major Learning and Challenges of the Study 25 7 List of Tables 1. Number of Colonies in the Country 8 2. Rehabilitation Centre and Hospital cum Rehabilitation Centre 11 3. Number of Districts with Colonies as Against Total Number of 18 Districts in the State/UT 4. District with Highest Number of Colonies and Their Demographic 19 Profile 5. Demographic Information of the Colonies 22 End Discrimination, Spread Smile........... Page 2 Identification and Validation of Leprosy Colonies in India: A Study Report 6. Information of the Affected Persons in the Colonies 24 8 List of Annexure 1. Study Tool: Survey Questionnaire 30 2. -

District Sub-Division Block/Ulb Name & Code

LIST OF FAIR PRICE SHOPS ENABLED FOR ONE NATION ONE RATION CARD PROGRAMME DISTRICT SUB-DIVISION BLOCK/ULB NAME & CODE NUMBER OF THE ONORC ENABLED FAIR PRICE SHOPS ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101G002-PEO, CHHELIAPADA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101G007-PEO, BALASINGHA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P038-PABAN BEHERA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P040-ROHIT KUMAR SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P046-PRAMOD DEHURY ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P048-SRIDHARA SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P054-GAGAN SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P059-BAIJAYANTI BEHERA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P061-CHHABI NARAYANA SETHA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P062-DARABA SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P064-JANAKA MAHAPATRA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P070-KUMUDA KUMAR BISWAL ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P072-TRINATH SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P074-BINUDHAR DEHURY ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P075-PRATAP CH. BEHERA ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P080-PABITRA DEHURY ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P083-AJATI SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P084-SARAT CH. SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P089-BISESWAR PATTNAIK ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P092-MRUTYUJAYA SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P093-RATNAKAR SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P098-PRADEEP DAS ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P110-GOPAL BISWAL ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P117-PRASANTA KUMAR PRADHAN ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P126-PITABASH SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P128-GADADHAR MAHAKUD ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P129-NILAKANTHA SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P134-KRUTIBAS PRADHAN ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P136-KUSHNA CHANDRA SAHU ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P139-SESADEVA ROUT ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P145-PITAMBER PRADHAN ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P160-UPENDRA DEHURY ANGUL ANGUL ANGUL 0101P207-NIRUPAMA -

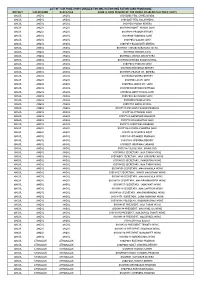

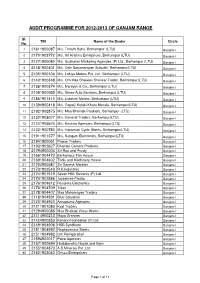

Ganjam Range

AUDIT PROGRAMME FOR 2012-2013 OF GANJAM RANGE Sl. TIN Name of the Dealer Circle No. 1 21611900087 M/s. Trinath Sahu, Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 2 21701903772 M/s. Sri Krishna Enterprises, Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 3 21271900080 M/s. Sudhakar Marketing Agencies (P) Ltd., Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 4 21481900401 M/s. Doki Satyanarayan Subudhi, Berhampur(LTU) Ganjam-I 5 21051900104 M/s. Lohiya Motors Pvt. Ltd., Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 6 21401900348 M/s. Om Maa Bhawani Shankar Trader, Berhampur,(LTU) Ganjam-I 7 21361900374 M/s. Narayan & Co., Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 8 21091900955 M/s. Shree Auto Services,.Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 9 21851901410 M/s. Lakshmi Motors, Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 10 21394900418 M/s. Gopalji Ketaki Khara Masala, Berhampur(LTU) Ganjam-I 11 21921902875 M/s. Maa Bhairabi Products, Berhampur (LTU) Ganjam-I 12 21201903077 M/s. General Traders, Berhampur(LTU) Ganjam-I 13 21241905674 M/s. Krishna Agencies, Berhampur(LTU) Ganjam-I 14 21321900780 M/s. Hanuman Cycle Stores, Berhampur(LTU) Ganjam-I 15 21911901377 M/s. Sangam Electronics, Berhampur(LTU) Ganjam-I 16 21941900051 Pawan Traders Ganjam-I 17 21931902627 Bhairabi Cement Products Ganjam-I 18 21794900004 Sri Rao and Prusty Ganjam-I 19 21661904473 Berhampur Fan House Ganjam-I 20 21691904602 Tools and Machinery House Ganjam-I 21 21704900587 Sri Ganesh Marbles Ganjam-I 22 21731902543 R.K.Industries Ganjam-I 23 21741901519 Seven Hills Solvents (P) Ltd Ganjam-I 24 21741902586 Jayashree Plastic Ganjam-I 25 21761904612 Ranjeeta Electronics Ganjam-I 26 21761904709 Trilok Ganjam-I -

Tourist Information

You are here: Home » Tourist Info Tourist Information Bhitarkanika: Bhitarkanika Chilika: Chilika is the largest is a beautiful National Park which is home to more than brackish water lake of Asia. It stretches across the 215 kind of species of birds, king cobra, salt-water length of three districts of Odisha namely Puri, Khurda crocodiles and Indian python. It enjoys the status of and Ganjam. The lake is famous for being a habitat to being the second largest mangrove ecosystem in India various species of migratory birds in the winter season. after the Sundarbans. The place is a very noted tourist It is also home to the endangered species of Irrawaddy destination in Odisha and a large number of visitors dolphin. There is a temple named Kalijai temple situated flock around this place every year. World's largest Olive on an island in the middle of Chilika lake. Hundreds of Ridely sea turtles are found in Gaharimatha of devotees visit the temple everyday to pay homage to Bhitarkanika which is the only marine wildlife sanctuary goddess Kalijai. Read More » of Odisha. Read More » Khandagiri and Udaygiri: Odisha State Museum: The Khandagiri and Udaygiri caves are situated in the city of State Museum is situated in Bhubaneswar city. It has a Bhubaneswar. These ancient caves have a great large collection of ancient coins, sculptures stone historical importance. It is an important tourist place of inscriptions, bronze tools and traditional musical Bhubaneswar. The Udaygiri caves are approximately instruments. The museum was founded by two eminent 135 ft high. Beautiful sculptures can be found on the professors of Revenshaw college, N.C. -

List of Pollution Testing Centers and Mobile Units

List of Pollution Testing Units Name of the Linked with SL NO. NO. Name of the PTU PUC Check Vehicle Type Email ID Contact No. Region VAHAN Angul 1 ANGUL MINES & M Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 7008542289 YES 2 ANGUL MINES & M Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 7008542289 YES 3 SONNY ONLINE PUC UNIT Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 9437901666 YES 4 SONNY ONLINE PUC UNIT Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 9437901666 YES 5 JHANSI MOBILE POLLUTION TESTING CENTRE Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 9937050036 YES 6 JHANSI MOBILE POLLUTION TESTING CENTRE Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 9937050036 YES 7 M/S DIAMOND ENTERPRISES Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 9437157248 YES 8 M/S DIAMOND ENTERPRISES Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 9437157248 YES 9 GOLDEN DIESELS Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 9437943521 YES 10 GOLDEN DIESELS Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 9437943521 YES 11 HIGHWAY MOBILE PTU Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 7978004259 YES 12 HIGHWAY MOBILE PTU Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 7978004259 YES 13 JAMUNA AUTO Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 9937050036 YES 14 MAA LOVHI MOBILE POLLUTION TESTING UNIT Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 8917248226 YES 15 MAA LOVHI MOBILE POLLUTION TESTING UNIT Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 8917248226 YES 16 S & S MOTORS Petrol/CNG/LPG Vehicle [email protected] 9438272270 YES 1 17 S & S MOTORS Diesel Vehicle [email protected] 9438272270 -

Report on Business Register, Odisha, Shop & Commercial Establishment

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA Report on Business Register,Odisha (Shop & Commercial Establishment Act) Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Odisha Bhubaneswar SURESH CHANDRA MAHAPATRA,IAS Tel : 0674-2536882 (O) Development Commissioner-Cum- : 0674-2322617 Additional Chief Secretary & Secy. to Govt. Fax : 0674-2536792 P & C Department Email : [email protected] MESSAGE I am glad to know that Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Odisha has brought out the final Report of "District wise Enterprises Registered under Shop & Commercial Establishment Act" for publication of Business Register, 2013-14 in the State. It is an important source of information for the statistical analysis of the business population and its demography. The gigantic task of Survey on Business Register undertaken by the officers and staff of DE&S is praiseworthy. I hope this publication would be useful for policy making in the Government. (Suresh Chandra Mahapatra) ସଙ୍କର୍ଷଣ ସାହୁ, ଭା.ପ.ସେ ଅର୍ଥନୀତି ଓ ପରିସଂ孍ୟାନ ଭବନ ନିସଦେଶକ Arthaniti ‘O’ Parisankhyan Bhawan ଅର୍େନୀତି ଓ ପରିେଂଖ୍ୟାନ HOD Campus, Unit-V Sankarsana Sahoo, ISS Bhubaneswar -751001, Odisha Director Phone : 0674 -2391295 Economics & Statistics e-mail : [email protected] Foreword Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India have introduced for preparation of National Business Register. Preparation of Business Register at State Level is a part of it. It aims to verify the physical existence of the establishments registered under seven Registering Authorities in the State. Directorate of Economics & Statistics (DE&S),Odisha conducted field survey on Business Register,2013 throughout the State on complete enumeration basis for collection of data on establishments and enterprises registered under seven Registering Authorities as on 2011-12 and functioning in the areas. -

MSME-DI, Cuttack Explained the Objective of Organizing the Programme

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF MICRO SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES MSME DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE MSME DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE Vikash Sadan, College Square, Cuttack-753003 Tel: 0671 - 2548049/2548077 Fax: 0671- 2548006 E-Mail [email protected] Website www.msmedicuttack.gov.in Udyami Helpline 1800 180 6763 1 CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION AND GEOGRAPHICAL COVERAGE OF THE INSTITUTE AND ITS BRANCH OFFICES The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Institute, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Government of India, Cuttack along with its two Branches at Rourkela and Rayagada has been functioning under the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Organization (MSMEDO), Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Government of India, with an objective to promote and develop MSME sector in the state by rendering various services. Workshops at Cuttack, Rourkela & Rayagada are providing common facility services to the units as well as imparting training to candidates to sharpen their skills to improve the productivity in their concerned units. The main activities of this Institute includes rendering techno-economic and managerial consultancy to the existing as well as new generation entrepreneurs in the field of chemical, mechanical, metallurgy, leather and Footwear, glass & ceramics, electrical, electronics, hosiery, industrial management, economics & statistics etc. besides providing training facilities under ESDP, EDP, MDP & BSDP programmes. Conducting Industrial Potentiality Survey of Districts and specific Cluster