1842 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 41

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready to Launch Lions Take on the Diabetes Epidemic

2017 SEPTEMBER LION READY TO LAUNCH LIONS TAKE ON THE DIABETES EPIDEMIC Children with diabetes enjoy their summertime at Lions Camp Merrick in Maryland. LIONMAGAZINE.ORG The greatest stories on Earth just got better. Introducing the LION Magazine app Instant access to a world of stories An exciting multimedia user-experience Available on iPhone and iPad today Available on Android by the end of 2017 Beginning January 2018, LION will publish 6 bi-monthly print and digital issues, plus 5 extra digital-only issues. Don’t miss a single issue. Download your LION Magazine App today! LionMagazine.org //SEPTEMBER 2017 18 Volume 100 Number 2 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 18 03 President’s Message A New Role for 08 First Roar A New Century Lions are taking on diabetes in 12 One of Us 26 our second century. 14 Service 26 Super Teacher 16 Service Abroad What lies behind a great teacher? Sometimes it’s Lions. 44 Foundation Impact 30 Targeting Fun Young Lions at Michigan State University bring joy—and Nerf guns—to seniors. 36 30 A Name with Legs “Lions”—our name has helped forge our identity. 36 SEPTEMBER 2017 // LION 1 Enhance your digital LION experience. Click on “HELP” in the toolbar above for instructions on how to make the most of the digital LION. 101st International Convention Las Vegas, Nevada, USA June 29-July 3 CONTACTING THE LION WE SERVE For change of address, non-receipt of the magazine and other subscription issues, contact 630-468-6982 or [email protected]. For all other inquiries call 630-571-5466. -

1843 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 43

Kenya Past and Present Issue 43 Kenya Past and Present Editor Peta Meyer Editorial Board Marla Stone Patricia Jentz Kathy Vaughan Kenya Past and Present is a publication of the Kenya Museum Society, a not-for-profit organisation founded in 1971 to support and raise funds for the National Museums of Kenya. Correspondence should be addressed to: Kenya Museum Society, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Email: [email protected] Website: www.KenyaMuseumSociety.org Statements of fact and opinion appearing in Kenya Past and Present are made on the responsibility of the author alone and do not imply the endorsement of the editor or publishers. Reproduction of the contents is permitted with acknowledgement given to its source. We encourage the contribution of articles, which may be sent to the editor at [email protected]. No category exists for subscription to Kenya Past and Present; it is a benefit of membership in the Kenya Museum Society. Available back issues are for sale at the Society’s offices in the Nairobi National Museum. Any organisation wishing to exchange journals should write to the Resource Centre Manager, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya, or send an email to [email protected] Designed by Tara Consultants Ltd ©Kenya Museum Society Nairobi, April 2016 Kenya Past and Present Issue 43, 2016 Contents KMS highlights 2015 ..................................................................................... 3 Patricia Jentz To conserve Kenya’s natural and cultural heritage ........................................ 9 Marla Stone Museum highlights 2015 ............................................................................. 11 Juliana Jebet and Hellen Njagi Beauty and the bead: Ostrich eggshell beads through prehistory .................................................. 17 Angela W. -

The Lamu House - an East African Architectural Enigma Gerald Steyn

The Lamu house - an East African architectural enigma Gerald Steyn Department of Architecture of Technikon Pretoria. E-mail: [email protected]. Lamu is a living town off the Kenya coast. It was recently nominated to the World Heritage List. The town has been relatively undisturbed by colonization and modernization. This study reports on the early Swahili dwelling, which is still a functioning type in Lamu. It commences with a brief historical perspective of Lamu in its Swahili and East African coastal setting. It compares descriptions of the Lamu house, as found in literature, with personal observations and field surveys, including a short description of construction methods. The study offers observations on conservation and the current state of the Lamu house. It is concluded with a comparison between Lamu and Stone Town, Zanzibar, in terms of house types and settlement patterns. We found that the Lamu house is the stage for Swahili ritual and that the ancient and climatically uncomfortable plan form has been retained for nearly a millennium because of its symbolic value. Introduction The Swahili Coast of East Africa was recentl y referred to as " ... this important, but relatively little-knqwn corner of the 1 western Indian Ocean" • It has been suggested that the Lamu Archipelago is the cradle of the Swahili 2 civilization . Not everybody agrees, but Lamu Town is nevertheless a very recent addition to the World Heritage Lise. This nomination will undoubtedly attract more tourism and more academic attention. Figure 1. Lamu retains its 19th century character. What makes Lamu attractive to discerning tourists? Most certainly the natural beauty and the laid back style. -

'Mau Mau' and Colonialism in Kenya

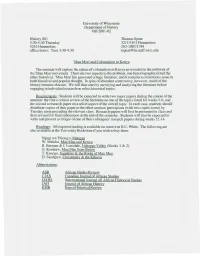

University of Wisconsin Department of History Fall2001-02 History 861 Thomas Spear 3:30-5:30 Thursday 3211/5101 Humanities 5245 Humanities 263-1807/1784 office hours: Tues 3:30-4:30 tspear@facstaff. wisc.edu 'Mau Mau' and Colonialism in Kenya The seminar will explore the nature of colonialism in Kenya as revealed in the outbreak of the 'Mau Mau' movement. There are two aspects to the problem: one historiographical and the other historical. 'Mau Mau' has generated a huge literature, and it remains a contentious issue in both historical and popular thought. In spite of abundant controversy, however, much of the history remains obscure. We will thus start by surveying and analyzing the literature before engaging in individual research on select historical topics. Requirements: Students will be expected to write two major papers during the course of the seminar: the first a critical review of the literature on one of the topics listed for weeks 2-9, and the second a research paper on a select aspect of the overall topic. In each case, students should distribute copies oftheir paper to the other seminar participants (with two copies to me) by Tuesday noon preceding the relevant class. Research papers will first be presented in class and then revised for final submission at the end of the semester. Students will also be expected to write and present a critique of one of their colleagues' research papers during weeks 12-14. Readings: All required reading is available on reserve at H. C. White. The following are also available at the University Bookstore if you wish to buy them: Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Matigari W. -

Phytolith Analysed to Compare Changes in Vegetation Structure of Koobi Fora and Olorgesailie Basins Through the Mid- Pleistocene-Holocene Periods

Phytolith analysed to Compare Changes in Vegetation Structure of Koobi Fora and Olorgesailie Basins through the Mid- Pleistocene-Holocene Periods. By KINYANJUI, Rahab N. Student number: 712138 Submitted on 28th February, 2017 Submitted the revised version on 22nd February, 2018 Declaration A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Science in fulfilment of the requirements for PhD degree. At School of Geosciences, Evolutionary Studies Institute (ESI) University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg South Africa. I declare that this is my own unaided work and has not been submitted elsewhere for degree purposes KINYANJUI, Rahab N. Student No. 712138 ii Abstract Phytolith analyses to compare changes in vegetation structure of Koobi Fora and Olorgesailie Basins through Mid-Pleistocene-Holocene Periods. By Rahab N Kinyanjui (Student No: 712138) Doctor of Philosophy in Palaeontology University of Witwatersrand, South Africa School of Geological Sciences, Evolutionary Science Institute (GEOS/ESI) Supervisor: Prof Marion Bamford. The Koobi Fora and Olorgesailie Basins are renowned Hominin sites in the Rift Valley of northern and central Kenya, respectively with fluvial, lacustrine and tuffaceous sediments spanning the Pleistocene and Holocene. Much research has been done on the fossil fauna, hominins and flora with the aim of trying to understand when and how the hominins evolved, and how the environment impacted on their behaviour, land-use and distribution over time. One of the most important factors in trying to understand the hominin-environment relationship is firstly to reconstruct the environment. Important environmental factors are the climate, rate or degree of climate change, vegetation structure and resources, floral and faunal resources. Vegetation structure/composition is a key component of the environments and, it has been hypothesized the openness and/or closeness of vegetation structure played a key role in shaping the evolutionary history not only of man but also other mammals. -

News ... of the Humane Society of the United States 16(4)

November 1971 ri ~ li c·~~,, f~ij h.,..) ~ ~;:: ),~*' L1o r~~ot Hernove of The Humane Society of the United States HSUS Releases HSUS Gives New Award Tufty from Tank HSUS has succeeded in springing To ffBorn Free'' Author Tuffy the Bengal tiger from his glass cage The Humane Society of the United States took a leap forward in atop a health spa bar and relocating him cementing its relationship with the ecology-conservation movement and in a natural habitat zoo in Texas. in establishing a cooperative spirit with the veterinary profession during HSUS's exotic animal specialist Sue its 1971 Annual Conference in Newport, R.I., last month. Pressman vowed to free the 3-year-old The dramatic highlight of the meeting, author of Born Free, who flew from her animal after visiting him at the White however, was the dedication of the new home in Kenya to accept the award. Plains, N.Y., spa last summer. Because the Joseph Wood Krutch Award for signifi Mrs. Adamson said she accepted the size of tiger quarters is not covered by cant contribution towards the improve award for Elsa, the lioness that she raised state or federal statute, HSUS was able to ment of life and environment. from a cub and later returned to the wild. get the health club owners to give up Mrs. Krutch, the naturalist's widow, Program Chairman Roger Caras, a Tuffy only through pressure. was special guest of honor, accepting the close friend of Mrs. Adamson, presented Letters from HSUS members and first copy of the medal from Pulitzer the author with a check for $1,000 from other concerned people poured into the Prize winning poet Mark Van Doren, a HSUS for Mrs. -

Lake Turkana National Parks - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Lake Turkana National Parks - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2017 (archived) Finalised on 26 October 2017 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Lake Turkana National Parks. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Lake Turkana National Parks عقوملا تامولعم Country: Kenya Inscribed in: 1997 Criteria: (viii) (x) The most saline of Africa's large lakes, Turkana is an outstanding laboratory for the study of plant and animal communities. The three National Parks serve as a stopover for migrant waterfowl and are major breeding grounds for the Nile crocodile, hippopotamus and a variety of venomous snakes. The Koobi Fora deposits, rich in mammalian, molluscan and other fossil remains, have contributed more to the understanding of paleo-environments than any other site on the continent. © UNESCO صخلملا 2017 Conservation Outlook Critical Lake Turkana’s unique qualities as a large lake in a desert environment are under threat as the demands for water for development escalate and the financial capital to build major dams becomes available. Historically, the lake’s level has been subject to natural fluctuations in response to the vicissitudes of climate, with the inflow of water broadly matching the amount lost through evaporation (as the lake basin has no outflow). The lake’s major source of water, Ethiopia’s Omo River is being developed with a series of major hydropower dams and irrigated agricultural schemes, in particular sugar and other crop plantations. -

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-6 Issue-5, May 2021

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-6 Issue-5, May 2021 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE ISSN-2213-1356 www.ijirk.com A HISTORY OF CONFLICT BETWEEN NYARIBARI AND KITUTU SUB-CLANS AT KEROKA IN NYAMIRA AND KISII COUNTIES, KENYA, 1820 - 2017 Samuel Benn Moturi (MA-History), JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA, UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY GESIAGA SECONDARY SCHOOL, P.O Box 840-40500 Nyamira-Kenya Dr. Isaya Oduor Onjala (PhD-History), JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, P.O Box 210-40601, Bondo-Kenya Dr. Fredrick Odede (PhD-History), JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, P.O Box 210-40601, Bondo-Kenya ABSTRACT A lot of research done on conflict and disputes between communities, nations and organized groups across the globe. Little, however done on conflicts involving smaller groups are within larger communities. The overall image that emerges, therefore, is that conflicts and disputes only occur between communities, nations, and specially organized groups, a situation which is not fully correct, as far as the occurrence of conflict is concerned. This study looked at a unique situation of conflict between Nyaribari and Kitutu who share the same origin, history and cultural values yet have been engaged in conflict since the 19th century. The purpose of this study was to trace the history of the Sweta Clan and relationship between Nyaribari and Kitutu sub-clans. Examine the nature, source and impact of the disputes among the Sweta at Keroka town and its environ, which www.ijirk.com 57 | P a g e International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge ISSN-2213-1356 forms the boundary between the two groups and discuss the strategies employed to cope with conflicts and disputes between the two parties. -

Ton Dietz University of Leiden, African Studies Centre Leiden META KNOWLEDGE ABOUT AREAS. the EXAMPLE of POKOT

Ton Dietz University of Leiden, African Studies Centre Leiden META KNOWLEDGE ABOUT AREAS. THE EXAMPLE OF POKOT Paper for the Africa Knows! Conference, panel 16: “Country/Region-specific Knowledge Development Histories in Africa” Abstract Area studies have a long history, and so have academic centres dealing with specific areas (like the African Studies Centres) or the specific journals dealing with certain areas (like the Journal of Eastern African Studies). However, very few area studies specialists use an approach to study the historical development of knowledge about a specific area, as a kind of meta knowledge study. In this paper I will try to show what the knowledge development history is about the areas of the Pokot in Kenya and Uganda: what is the 'harvest' of specific knowledge about that area and its people? Who did influence whom? Where did the people come from who studied that area, and how did that change during a 150-year long period of written sources about the area? And what does it tell us about the 'knowledge hypes', the major topics studied in particular periods? With the assistance of google scholar it is possible to reconstruct the networks of references used in academic (and other) studies, next to doing a detailed analysis of the references used in scholarly work about an area. One of the interesting aspects in this paper will be the study of the types of sources used: academic/non-academic, languages used, disciplines used or neglected. This is work in progress. As an hypothesis we can already formulate the statement that the specific topic studied about an area often tells more about the (scientific/societal) questions relevant to the countries where scholars come from, than about the questions that are relevant for the situation in the particular area that is being studied. -

A History of Nairobi, Capital of Kenya

....IJ .. Kenya Information Dept. Nairobi, Showing the Legislative Council Building TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Chapter I. Pre-colonial Background • • • • • • • • • • 4 II. The Nairobi Area. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 29 III. Nairobi from 1896-1919 •• • • • • • • • • • 50 IV. Interwar Nairobi: 1920-1939. • • • • • • • 74 V. War Time and Postwar Nairobi: 1940-1963 •• 110 VI. Independent Nairobi: 1964-1966 • • • • • • 144 Appendix • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 168 Bibliographical Note • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 179 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 182 iii PREFACE Urbanization is the touchstone of civilization, the dividing mark between raw independence and refined inter dependence. In an urbanized world, countries are apt to be judged according to their degree of urbanization. A glance at the map shows that the under-developed countries are also, by and large, rural. Cities have long existed in Africa, of course. From the ancient trade and cultural centers of Carthage and Alexandria to the mediaeval sultanates of East Africa, urban life has long existed in some degree or another. Yet none of these cities changed significantly the rural character of the African hinterland. Today the city needs to be more than the occasional market place, the seat of political authority, and a haven for the literati. It remains these of course, but it is much more. It must be the industrial and economic wellspring of a large area, perhaps of a nation. The city has become the concomitant of industrialization and industrialization the concomitant 1 2 of the revolution of rising expectations. African cities today are largely the products of colonial enterprise but are equally the measure of their country's progress. The city is witness everywhere to the acute personal, familial, and social upheavals of society in the process of urbanization. -

Later Stone Age Toolstone Acquisition in the Central Rift Valley of Kenya

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 18 (2018) 475–486 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Later Stone Age toolstone acquisition in the Central Rift Valley of Kenya: T Portable XRF of Eburran obsidian artifacts from Leakey's excavations at Gamble's Cave II ⁎ ⁎⁎ Ellery Frahma,b, , Christian A. Tryonb, a Yale Initiative for the Study of Ancient Pyrotechnology, Council on Archaeological Studies, Department of Anthropology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States b Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Cambridge, MA, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The complexities of Later Stone Age environmental and behavioral variability in East Africa remain poorly Obsidian sourcing defined, and toolstone sourcing is essential to understand the scale of the social and natural landscapes en- Raw material transfer countered by earlier human populations. The Naivasha-Nakuru Basin in Kenya's Rift Valley is a region that is not Naivasha-Nakuru Basin only highly sensitive to climatic changes but also one of the world's most obsidian-rich landscapes. We used African Humid Period portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) analyses of obsidian artifacts and geological specimens to understand pat- Hunter-gatherer mobility terns of toolstone acquisition and consumption reflected in the early/middle Holocene strata (Phases 3–4 of the Human-environment interactions Eburran industry) at Gamble's Cave II. Our analyses represent the first geochemical source identifications of obsidian artifacts from the Eburran industry and indicate the persistent selection over time for high-quality obsidian from Mt. Eburru, ~20 km distant, despite changes in site occupation intensity that apparently correlate with changes in the local environment. -

On the Conservation of the Cultural Heritage in the Kenyan Coast

THE IMPACT OF TOURISM ON THE CONSERVATION OF THE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE KENYAN COAST BY PHILEMON OCHIENG’ NYAMANGA - * • > University ol NAIROBI Library "X0546368 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE INSTITUTE OF ANTHROPOLOGY, GENDER AND AFRICAN STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2008 DECLARATION This thesis is my original work. It has not been presented for a Degree in any other University. ;o§ Philemon Ochieng’ Nyamanga This thesis has been submitted with my approval as a university supervisor D ate..... J . l U ■ — • C*- imiyu Wandibba DEDICATION This work is dedicated to all heritage lovers and caregivers in memory of my late parents, whose inspiration, care and love motivated my earnest quest for knowledge and committed service to society. It is also dedicated to my beloved daughter. Leticia Anvango TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- v List of Figures----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------v List of P la tes---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Abbreviations/Acronvms----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- vii Acknowledgements-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------viii