Locally Generated Transportation Modes of the Developing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bay Drive NOVEMBER 19, 2018 UPDATED JANUARY 31, 2019

Miami Beach Neighborhood Greenways Bay Drive NOVEMBER 19, 2018 UPDATED JANUARY 31, 2019 p 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary p. 5 Goals and Objectives p. 7 Bay Drive Neighborhod Greenway p. 9 Existing Conditions p. 11 BAY DRIVE Bay Drive - Segment 1 p. 12 Bay Drive - Segment 2 p. 14 Bay Drive - Segment 3 p. 16 Landscaping p. 18 Safety and Access p. 19 Traffic Calming p. 20 71ST STREET AND NORMANDY DRIVE 71st Street and Normandy Drive p. 23 71st Street East - Segment 1 p. 24 71st Street West - Segment 2 p. 26 Normandy Drive East - Segment 1 p. 28 Normandy Drive West - Segment 2 p. 30 East Bridge p. 32 West Bridge p. 33 Landscaping p. 34 Safety - Bike Box p. 35 Parking Impact Analysis p. 36 Appendix Cost Estimates p. 42 Parking Replacement Analysis p. 48 Sidewalks Gap Analysis p. 56 Summary of Meetings p. 62 p 2 p 3 p 4 BAY DRIVE | City of Miami Beach Neighborhood Greenways EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The Bay Drive Neighborhood Greenway concepts were then refined and reviewed extensively with Transportation staff and The adopted 2016 Miami Beach Transportation Master Plan internal Miami Beach stakeholders. The concepts were also was built on a mode share goal and modal prioritization strategy presented to the North Beach Steering Committee on October adopted by Resolution 2015-29083 on July 8, 2015, which 25, 2017. Transportation toured the area with TCED staff on places pedestrians first; transit, bicycles, and freight second; December 7, 2017. The Transportation, Parking and Bicycle and private automobiles third. Projects in the Transportation Facilities Committee reviewed the North Beach Neighborhood Master Plan are intended to move Miami Beach towards this Greenways concepts on April 9, 2017 and June 11, 2018. -

Socio-Economic Profile of Cycle Rickshaw Pullers: a Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal January edition vol. 8, No.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 UDC:656.12-05:316.35]:303.6(540)"2010" SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE OF CYCLE RICKSHAW PULLERS: A CASE STUDY Jabir Hasan Khan, PhD Tarique Hassan, PhD candidate Shamshad, PhD candidate Department of Geography Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh Abstract The present paper is an attempt to analyze the socio-economic characteristics of cycle rickshaw pullers and to find out the causes of rickshaw pulling. The adverse effects of this profession on the health of the rickshaw pullers, the problems faced by them and their remedial measures have been also taken into account. The study is based on primary data collected through the field survey and direct questionnaire to the respondents in Aligarh city. The survey was carried out during the months of February and March, 2010. The overall analysis of the study reveals that the rickshaw pullers are one of the poorest sections of the society, living in abject poverty but play a pivotal role in intra-city transportation system. Neither is their working environment regulated nor their social security issues are addressed. They are also unaware about the governmental schemes launched for poverty alleviation and their accessibility in basic amenities and infrastructural facilities is also very poor. Keywords: Abject poverty, breadwinners, cycle rickshaw pullers, disadvantageous, intra- city transport, vulnerability 310 European Scientific Journal January edition vol. 8, No.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Introduction: The word rickshaw originates from the Japanese word ‘jinrikisha’, which literally means human-powered vehicle (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1993). -

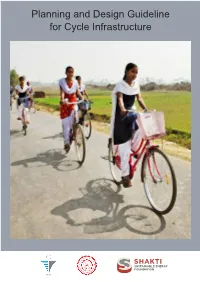

Planning and Design Guideline for Cycle Infrastructure

Planning and Design Guideline for Cycle Infrastructure Planning and Design Guideline for Cycle Infrastructure Cover Photo: Rajendra Ravi, Institute for Democracy & Sustainability. Acknowledgements This Planning and Design guideline has been produced as part of the Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation (SSEF) sponsored project on Non-motorised Transport by the Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. The project team at TRIPP, IIT Delhi, has worked closely with researchers from Innovative Transport Solutions (iTrans) Pvt. Ltd. and SGArchitects during the course of this project. We are thankful to all our project partners for detailed discussions on planning and design issues involving non-motorised transport: The Manual for Cycling Inclusive Urban Infrastructure Design in the Indian Subcontinent’ (2009) supported by Interface for Cycling Embassy under Bicycle Partnership Program which was funded by Sustainable Urban Mobility in Asia. The second document is Public Transport Accessibility Toolkit (2012) and the third one is the Urban Road Safety Audit (URSA) Toolkit supported by Institute of Urban Transport (IUT) provided the necessary background information for this document. We are thankful to Prof. Madhav Badami, Tom Godefrooij, Prof. Talat Munshi, Rajinder Ravi, Pradeep Sachdeva, Prasanna Desai, Ranjit Gadgil, Parth Shah and Dr. Girish Agrawal for reviewing an earlier version of this document and providing valuable comments. We thank all our colleagues at the Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme for cooperation provided during the course of this study. Finally we would like to thank the transport team at Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation (SSEF) for providing the necessary support required for the completion of this document. -

A Review on Feasibility Study of Providing Cycle Track in East Zone Area of Vadodara City

January 2018, Volume 5, Issue 1 JETIR (ISSN-2349-5162) A REVIEW ON FEASIBILITY STUDY OF PROVIDING CYCLE TRACK IN EAST ZONE AREA OF VADODARA CITY 1Urvi Patel, 2Jayesh Juremalani, 3Khushbu Bhatt 1M.tech student, 2Assistant professor, 3Assistant professor 1Transportation engineering 1Parul institute of engineering and technology, Vadodara,India Abstract—The “last mile” problem is becoming the increasingly serious problem during the process of development of the public transit. Traditional transit hardly meets the residents’ door to door travel demands, which reduce passenger satisfaction with the public transit. Also issues on carbon emission and energy saving have been taken seriously. The central concept to increasing bicycles for short-distance trips in an urban area as an alternative to motorised public transport or private vehicles, thereby reducing traffic congestion, noise, and air pollution. Targeted at low‐income groups the prime reasons for subscriptions were savings in time and money spent over other modes of transport. The main obstacle to boosting the bicycle as a regular mode of transport is safety problem due to mix motorized traffic. One option is to separate cyclists from motorists through exclusive bicycle priority lanes. A questionnaire survey will carried out from public what they want features in the bicycle track. Using that data we can design the bicycle track as per IRC-11 (cycle track design and layouts 1962). Index Terms— bicycle, transport, bicycling, motivation, non motorized modes I.INTRODUCTION As an emerging economy, India now faces urban challenges that are more complex than the western world, particularly due to the sheer size of the population and rapid pace of urbanization. -

Bicycles and Cycle-Rickshaws in Asian Cities: Issues and Strategies

76 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD 1372 Bicycles and Cycle-Rickshaws in Asian Cities: Issues and Strategies MICHAEL REPLOGLE An overview of the use and impacts of nonmotorized vehicles in for several decades offered employee commuter subsidies for Asian cities is provided. Variations in nonmotorized vehicle use, cyclists, cultivated a domestic bicycle manufacturing industry, economic aspects of nonmotorized vehicles in Asia, and facilities and allocated extensive urban street space to nonmotorized that serve nonmotorized vehicles are discussed, and a reexami nation of street space allocation on the basis of corridor trip length vehicle traffic. This strategy reduced the growth of public distribution and efficiency of street space use is urged. The re transportation subsidies while meeting most mobility needs. lationship between bicycles and public transportation; regulatory, Today, 50 to 80 percent of urban vehicle trips in China are tax, and other policies affecting nonmotorized vehicles; and the by bicycle, and average journey times in China's cities appear influence of land use and transportation investment patterns on to be comparable to those of many other more motorized nonmotorized vehicle use are discussed. Conditions under which Asian cities, with favorable consequences for the environ nonmotorized vehicle use should be encouraged for urban trans ment, petroleum dependency, transportation system costs, portation, obstacles to nonmotorized vehicle development, ac tions that could be taken to foster appropriate use of nonmoto_r and traffic safety. ized vehicles, and research needs are identified. EXTENT OF OWNERSHIP AND USE Nonmotorized vehicles-bicycles, cycle-rickshaws, and carts play a vital role in urban transportation in much of Asia. Bicycles are the predominant type of private vehicle in many Nonmotorized vehicles account for 25 to 80 percent of vehicle Asian cities. -

Design of Advanced Loading Cycle Rickshaw Rasika S

International Journal of Innovative and Emerging Research in Engineering Volume 3, Issue 10, 2016 Available online at www.ijiere.com International Journal of Innovative and Emerging Research in Engineering e-ISSN: 2394 – 3343 p-ISSN: 2394 – 5494 Design of Advanced Loading Cycle Rickshaw Rasika S. Khairkar a a PRMIT & R Badnera, Amravati, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT: The present paper is to design and development of loading cycle rickshaw. It includes the self weight of cycle rickshaw is reduced by replacing some heavier material with lighter one, the torque is nearly doubled by using gear train of torque multiplier mechanism and the unloading is done by tilting the rickshaw carriage about pivots provided on the frame. The purpose of this paper is to reduce the effort of the rickshaw puller and to have quick unloading mechanism of goods. This paper will lead to a safe, easy and comfortable mode of transport in three wheeled non-engine cargo. This is the long lasting mode of transport since it is not affected by fuel crisis and the green mode of transport thus will greatly reduce the pollution. Keywords: Loading cycle rickshaw, torque multiplier, load, unload, mechanism, aluminum sheet I. INTRODUCTION A cycle rickshaws are widely used for transportation throughout the India. The basic rickshaw is a three-wheeled tricycle design, pedalled by a human driver in the front and with a bench seat in the rear for conveying goods and luggage. There are an estimated eight million cycle rickshaw pullers in India alone, with many more in Bangladesh and other developing countries[1]. But cycle rickshaws are growing in popularity even in developed countries. -

Probike/Prowalk Florida City Comes up with the Right Answers Florida Bike Summit Brought Advocacy to Lawmakers' Door

Vol. 13, No. 2 Spring 2010 OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE FLORIDA BICYCLE ASSOCIATION, INC. Reviewing the April 8 event. Florida Bike Summit brought Lakeland: ProBike/ProWalk advocacy to lawmakers’ doorstep Florida city comes up with the right answers by Laura Hallam, FBA Executive Director photos: by Herb Hiller Yes, yes, yes and no. Woman’s Club, Lakeland Chamber of Keri Keri Caffrey Four answers to four questions you may be Commerce, fine houses and historical mark- asking: ers that celebrate the good sense of people 1. Shall I attend ProBike/ProWalk Florida who, starting 125 years ago, settled this rail- in May? road town. 2. Shall I come early and/or stay in I might add about those people who settled Lakeland after the conference? Lakeland that they also had the good fortune 3. Is Lakeland not only the most beautiful of having Publix headquarter its enterprise mid-sized city in Florida but also, rare here, so that subsequent generations of among cities of any size, year by year get- Jenkins folk could endow gardens, children’s ting better? play areas and everything else that makes photos: Courtesy of Central Visitor Florida & Bureau Convention Above: Kathryn Moore, Executive Director embers of FBA from of the So. Fla. Bike Coalition (right), works around the state gath- the FBA booth. Below: Representative ered with Bike Florida Adam Fetterman takes the podium. at the Capitol for the 2nd annual Florida Bike Summit. Modeled after the high- ly successful National PAID Bike Summit that recently NONPROFIT U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. PERMIT No. -

Socio-Economic Profile of Cycle Rickshaw Pullers: a Case Study

European Scientific Journal January edition vol. 8, No.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 UDC:656.12-05:316.35]:303.6(540)"2010" SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE OF CYCLE RICKSHAW PULLERS: A CASE STUDY Jabir Hasan Khan, PhD Tarique Hassan, PhD candidate Shamshad, PhD candidate Department of Geography Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh Abstract The present paper is an attempt to analyze the socio-economic characteristics of cycle rickshaw pullers and to find out the causes of rickshaw pulling. The adverse effects of this profession on the health of the rickshaw pullers, the problems faced by them and their remedial measures have been also taken into account. The study is based on primary data collected through the field survey and direct questionnaire to the respondents in Aligarh city. The survey was carried out during the months of February and March, 2010. The overall analysis of the study reveals that the rickshaw pullers are one of the poorest sections of the society, living in abject poverty but play a pivotal role in intra-city transportation system. Neither is their working environment regulated nor their social security issues are addressed. They are also unaware about the governmental schemes launched for poverty alleviation and their accessibility in basic amenities and infrastructural facilities is also very poor. Keywords: Abject poverty, breadwinners, cycle rickshaw pullers, disadvantageous, intra- city transport, vulnerability 310 European Scientific Journal January edition vol. 8, No.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Introduction: The word rickshaw originates from the Japanese word ‘jinrikisha’, which literally means human-powered vehicle (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1993). -

Delhi Development Authority Unified Traffic & Transportation Infrastructure (Plg

DELHI DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY UNIFIED TRAFFIC & TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE (PLG. & ENGG.) CENTRE 2nd Floor, Vikas Minar, New Delhi. Phone No. 23379042, Telefax: 23379931 E-mail: [email protected] BICYCLE SHARING POLICY FOR NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI 1.0 Background Bicycle sharing system is a public transport system in which bicycles are made available to multiple users for short duration trips, offering an option of returning the vehicles to different destinations. It is an eco-friendly, affordable and health-friendly system which would be an attractive travel mode option for all income and age groups. Bicycle sharing systems are mostly integrated with public transit stations to provide last mile connectivity or provided in dense areas to facilitate short duration work and/ or personal trips. Bicycle Share system is designed to be used by one and all, but it may find use more frequently by daily commuters for last-mile connectivity, residents and office employees to run general errands in the vicinity, as well as by tourists and students. Using Cycle Sharing is considerably cheaper than using Intermediate Public Transport (IPT) like cycle rickshaw, auto rickshaw or shared auto rickshaw. Moreover, one is flexible to choose one’s own route on a cycle sharing than using a few IPT modes like shared rickshaw which run on specific routes and may not necessarily connect directly to one’s destination. Additionally, cycling has many benefits; it can be treated as exercise with several health and social and environmental benefits. 1.1 Consultation meeting held with Cycle Sharing operators and other stakeholders held under VC, DDA on 10.04.2015: DDA has initiated the project of project of bicycle sharing scheme for Dwarka based on the decision of the 45th Governing Body meeting of UTTIPEC dt. -

Fazilka Ecocabs World's First Dial-A-Rickshaw Scheme

Fazilka Ecocabs World’s first Dial-a-Rickshaw scheme Experiences and Lessons Case Studies in Sustainable Urban Transport #9 Published by About the authors Vedant Goyal is a project officer for the Sustainable Navdeep Asija (born in Fazilka, Punjab, India) is the Urban Transport Project at GIZ India. He is based in founder of dial-a-cycle rickshaw concept known as Eco- Delhi and is involved in GIZ India’s research, policy and cabs for which he won the 2011 National Award of Excel- project initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable urban lence by the Ministry of Urban Development, Government transport in Indian cities. Vedant was the key member of of India. Mr Asija is currently pursuing his Ph. D. on Road the Sustainable Urban Transport Project initiated by the Safety from the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi and Government of India (GoI) with the support of the Global works for the Government of India as a consultant. Environment Facility (GEF), the World Bank and UNDP. Mr Asija’s biggest accomplishment is the development He is an integral part of GIZ India’s activities on further of the Ecocabs concept, which is a dial-a-cycle rickshaw research, information dissemination and policy-level equivalent to normal cab services that use gasoline-pow- engagement with key stakeholders at the city, state and ered automobiles. The recent development of advanced national level to take recommendations forward. IT tools and the spread of cell phones have made it possi- Vedant holds a Master of Science (Eng.) in Trans- ble to balance the supply and demand of passengers and port Planning and Engineering from the Institute of rickshaw taxis via a distributed fleet and automation. -

CHOUBASSI-THESIS-2015.Pdf

Copyright by Carine Choubassi 2015 The Thesis Committee for Carine Choubassi Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: An Assessment of Cargo Cycles in Varying Urban Contexts APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: C. Michael Walton Dan P. K. Seedah An Assessment of Cargo Cycles in Varying Urban Contexts by Carine Choubassi, B.E. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 A mio nipote, Elia. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, mentor, and friend, Dr. Dan Seedah for believing in me and supporting me every step of the way. This thesis would not have been possible without his optimism, perseverance, and continuous guidance which have been an inspiration to me every day. I will be forever grateful. I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. C. Michael Walton for giving me this opportunity to pursue my M.S. Degree here at UT Austin and the privilege of working with him and sharing his knowledge on a number of very interesting projects. Thank you for the constant encouragement. I would like to thank my colleagues at the Center for Transportation Research (CTR), Dr. Jennifer Duthie, Dr. Nan Jiang, and Jackson Archer for their help and technical support in completing my thesis. I would also like to thank Mohamad Cheblak and the Deghri Messengers for fostering my interest in this subject and showing me the true potential of cargo cycles. -

Bridging the Urban Transport Infrastructure Gap

Bridging the Urban Transport Infrastructure Gap In the Context of Smart and Resilient Cities – the Role of Private Sector and Public-Private-Partnerships. Background Paper for Twelfth Regional EST Forum in Asia. October 2019, Viet Nam. Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 4 1. Background ........................................................................................................................ 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 8 Making ‘smart’ choices about transport infrastructure ...................................................... 10 Making ‘smart’ choices about transport technologies ........................................................ 12 Asia’s urban infrastructure funding gap .............................................................................. 14 The role of the private sector in driving sustainable infrastructure provision .................... 15 Closing Comments for Section 1 .......................................................................................... 17 2. Overview of Urban Transport Infrastructure Gaps in Smart and Resilient Cities relevant to Asian cities .......................................................................................................................... 19 Sustainable transport for a smart and resilient city ...........................................................