A Seigniorage Perspective on the Introduction of a Palestinian Currency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

THREE KINGS Building Bnei Brak

See Page 35 $1.00 WWW.5TJT.COM VOL. 9 NO. 39 18 TAMMUZ 5769 xjbp ,arp JULY 10, 2009 INSIDE FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK SETTLERS SLAM ‘GOOD NEWS’ Essence Of Greatness BY LARRY GORDON Rabbi Avi Shafran 23 MindBiz The Impressive Mr. Oren Esther Mann, LMSW 24 Things may have become a Ding-Dong . bit safer for Israel for now—at Hannah Reich Berman 28 least in Washington, DC—as Bibi’s Inner Circle American-born scholar and Leslie Sussner 48 historian Michael Oren has assumed the position of the Middle East Piece Jewish State’s ambassador to Yochanan Gordon 59 the U.S. Of course, Israel needs a great myriad of things, but perhaps the void that needs filling most is the position of an articulate and A settlement community in Gush Etzion, pictured from a distance. effective spokesperson who The future of these communities, whose current population stands at over 500,000, is one of the many points of contention between Continued on Page 6 the U.S. and Israel. See Story, Page 47 LOOKING BACK, LOOKING AHEAD HEARD IN THE BAGEL STORE B Y RABBI live in the homeland of our SHALOM ROSNER nation, the land which so Building Bnei Brak many throughout our history Jetter–Stein Wedding. Ten months ago, I, along had yearned, aspired, and BY LARRY GORDON See Page 53 with my family, had the z’chut hoped for. Now, we, standing of fulfilling a mitzvah that on the shoulders of those who Ahh, the hustle and bustle Moshe, Aharon, and Miriam preceded us, had come back and the noise of the streets of could only dream of fulfilling. -

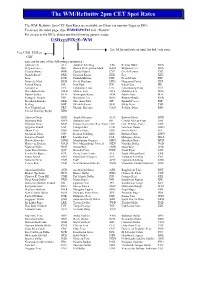

WM/Refinitiv 2Pm CET Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv 2pm CET Spot Rates The WM/ Refinitiv 2pm CET Spot Rates are available on Eikon via monitor Pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRESPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes : USDxxxFIXzE=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR or GBP xxx can be any of the following currencies : Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy Ariary -

North York Coin Club Founded 1960 MONTHLY MEETINGS 4TH Tuesday 7:30 P.M

North York Coin Club Founded 1960 MONTHLY MEETINGS 4TH Tuesday 7:30 P.M. AT Edithvale Community Centre, 131 Finch Ave. W., North York M2N 2H8 MAIL ADDRESS: NORTH YORK COIN CLUB, 5261 Naskapi Court, Mississauga, ON L5R 2P4 Web site: www.northyorkcoinclub.com Contact the Club : Executive Committee E-mail: [email protected] President ........................................Bill O’Brien Director ..........................................Roger Fox Auction Manager..........................Paul Johnson Phone: 416-897-6684 1st Vice President ..........................Henry Nienhuis Director ..........................................Paul Johnson Editor ..........................................Paul Petch 2nd Vice President.......................... Director ..........................................Andrew Silver Receptionist ................................Franco Farronato Member : Secretary ........................................Henry Nienhuis Junior Director ................................ Draw Prizes ................................Bill O’Brien Treasurer ........................................Ben Boelens Auctioneer ......................................Dick Dunn Social Convenor ..........................Bill O’Brien Ontario Numismatic Association Past President ................................Nick Cowan Royal Canadian Numismatic Assocation THE BULLETIN FOR MARCH 2017 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE NEXT MEETING Good day to all fellow numismatists and Speaking about the R.C.N.A., it’s not too TUESDAY, MARCH 28 our members and friends who receive -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

Forecasting the Exchange Rate of the Jordanian Dinar Versus the US Dollar Using a Box-Jenkins Seasonal ARIMA Model

b b International Journal of Mathematics and M Computer Science, 15(2020), no. 1, 27–40 CS Forecasting the Exchange Rate of the Jordanian Dinar versus the US Dollar Using a Box-Jenkins Seasonal ARIMA Model Remal Shaher Al-Gounmeein1,2, Mohd Tahir Ismail2 1Mathematics Department Al-Hussein Bin Talal University Jordan 2 School of Mathematical Sciences Universiti Sains Malaysia Malaysia email: [email protected], [email protected] (Received July 16, 2019, Accepted September 11, 2019) Abstract Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA) model was fitted for the time series data either to better understand the data or to predict the future points in the series (forecasting). Us- ing the forecasting for the exchange rate is very important at the na- tional, regional and international levels. It can help investors minimize financial risk as well maximize earnings in the volatility of the global economy. The aim of this study was to use the time series model to forecast the exchange rate of Jordan dinar based on the monthly data collected for Jordanian dinar vs US dollar. Exchange rate prediction is performed using two methods; Autoregressive Integrated Moving Av- erage (ARIMA) and Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Av- erage (SARIMA) time series. After comparing the forecasting method using ARIMA (1, 0, 1) and SARIMA (1, 0, 1)(1, 0, 0)12 models, we find that the second model shows a smaller mean absolute percentage er- ror (MAPE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error Key words and phrases: ARIMA, SARIMA, Jordanian Dinar, Modeling, R software, Time series, Forecasting. AMS (MOS) Subject Classifications: 37M10, 62M10, 91B84. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

Supported Currencies

AMERICAN EXPRESS GLOBAL MERCHANT SERVICES Supported Currencies Start Navigating Through the Global Marketplace with Multi-Currency Albanian Lek Danish Krone* Lesotho Loti Saudi Arabia Rial Algerian Dinar Djibouti Franc Liberian Dollar Serbian Dinar Armenian Dram Dominican Peso Libyan Dinar Seychelles Rupee Aruba Guilder Sierra Leone Leone Australian Dollar* East Caribbean Dollar Macau Pataca Singapore Dollar* Azerbaijanian Manat Egyptian Pound Macedonia Denar Solomon Islands Dollar Ethiopian Birr Malagasy Ariary Somali Shilling Bahamian Dollar Euro* Malawi Kwacha South African Rand* Bahraini Dinar Malaysian Ringgit Sri Lanka Rupee Fiji Dollar Bangladesh Taka Maldives Rufiyaa Swedish Krona* Barbados Dollar Mauritania Ouguiya Gambia Dalasi Swiss Franc* Belarussian Ruble Mauritius Rupee Georgian Lari Swaziland Lilangeni Belize Dollar Mexican Peso* Ghana Cedi Bermudian Dollar Moldovan Leu Taiwanese Dollar Gibraltar Pound Bhutan Ngultrum Mongolian Tugrik Tajik Somoni Guinea Franc Bosnia and Herzegovina Moroccan Dirham Tanzanian Shilling Guyana Dollar Convertible Marks Mozambique New Metical Thai Baht Guatemala Quetzal Botswana Pula Tonga Pa’anga Brunei Dollar Namibia Dollar Trinidad and Tobago Dollar Haiti Gourde Bulgarian Lev Nepalese Rupee Tunisian Dinar Hong Kong Dollar* Burundi Franc Netherlands Antillean Guilder Turkish Lira Hungarian Forint* New Zealand Dollar* Turkmenistan New Manat Honduras Lempira Cambodia Riel Nigerian Naira Uae Dirham Canadian Dollar* Iceland Krona Norwegian Krone* Uganda Shilling Cape Verde Escudo Indian Rupee -

Delegates Information Package

Delegates Information Package Venue ICAN2019 will be held in Aqabar, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan from 2 to 6 December 2019 at INTERCONTINENTAL AQABA RESORT King Hussein Street P.O. Box 2311 77110 Aqaba, Jordan Tel: +962 3 209 2222 Fax: +962 3 209 3315 Website: www.intercontinental.com/Aqaba Language The ICAN 2019 Event will be conducted in English. ICAN2019 is a paperless meeting, event materials will only be provided in electronic format. Accordingly, participants are required to bring their own portable computers/laptops configured with Microsoft Windows operating system. Delegates shall handle translation services for bilateral negotiation meetings. English and Arabic are well spoken in Jordan. Medical Clinic A medical clinic will be made available to ICAN Delegates throughout the event should participants require medical attention. In the event of emergency medical care, it is strongly recommended that participants should have travel insurance (including health) for the duration of their stay in Jordan and ensure that their insurance is applicable in Jordan. Furthermore, they should carry evidence of current health/ hospitalization insurance such as cards that may be produced to health institutions should the need arise. Participants are also encouraged to provide information during registration, on their next of kin who may be contacted on behalf of the participant should the need arise. Communication Services Worldwide direct connections are available, using the international code or telephone operator as necessary. From outside Jordan, dial +962 followed by the area code (for landline numbers) and the required number. Mobile telephone services are quite efficient in Jordan. Some of the main mobile telephone service providers are Zain, Orange, and Umniah. -

Currency the Jordanian Unit of Currency Is the Jordanian Dinar

Currency The Jordanian unit of currency is the Jordanian dinar, often abbreviated as JD. The JD is divided into 100 piasters, or 1000 fils. The JD is pegged to the U.S. dollar at a permanent exchange rate of 0.708 JDs to one U.S. dollar, and may be freely converted into U.S. dollars and visa versa. Language and Religion The official language of Jordan is Arabic, but many people also speak English. The major religion is Islam. Approximately 4% of the population is Christian. Shopping For shoppers Jordan offers a mix of new and old. Parts of Amman are lined with trendy shops where one can find the latest fashions. In the older souks one can find a plethora of traditional items to purchase including sand bottles and Arab "kefiyas,” big cotton headscarves in black and white or red and white. Jewelry is also popular. For traditional items, bargaining is encouraged. Sightseeing Jordan features something for everyone. For monument seekers, there is the ancient Nabateaean city of Petra, where temples and monuments are carved into the walls of a canyon. If ancient Rome is your thing, don’t forget to visit Jarash, which is just north of Amman. For desert lovers, one should checkout the breathtaking scenery of Wadi Rum. Arriving by Air Queen Alia International Airport (QAIA) is 32 kilometres (20 miles) south-east of Amman city centre and is Jordan's gateway to the world. Although numerous taxis link QAIA with Amman and other places near and far, airport access was given a big coach service.