Charles Hobart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Title: County Marshal DOT#: 377.667.-014 Employee: Claim

Job Title: County Marshal DOT#: 377.667.-014 Employee: Claim#: JOB ANALYSIS JOB TITLE : County Marshal JOB CLASSIFICATION Security Assistant II DICTIONARY OF OCCUPATIONAL TITLES (DOT) NUMBER: 377.667-014 DOT TITLE: Deputy Sheriff, Building Guard DEPARTMENT Sheriff’s Department DIVISION Criminal Investigations # OF POSITIONS IN THE DEPARTMENT WITH THIS JOB TITLE 25 FTE CONTACT’S NAME & TITLE Sgt. Mark Rorvik CONTACT’S PHONE (206) 296-9325 ADDRESS OF WORKSITE King Co. Courthouse 516 3rd Avenue # E167 Seattle WA 98104 VRC NAME Carol N. Gordon DATE COMPLETED 1/29/09 WORK HOURS: Work either 5- 8 hour shifts or 4-10 hour shifts between the hours of 6 am to 6 pm Monday-Friday. Saturday and Holidays noon-4pm. OVERTIME (Note: Overtime requirements may change at the employer’s discretion) Required: amount varies depending on court needs, vacation, sick leave, and training. JOB SUMMARY Provide protection and security to people at the King County Courthouse, the Maleng Regional Justice Center, the Youth Service Center, Harborview Mental Health Court, Office of the Public Defender/King County Veteran’s Program, and other buildings as assigned. ESSENTIAL ABILITIES FOR ALL KING COUNTY JOB CLASSIFICATIONS 1. Ability to demonstrate predictable, reliable, and timely attendance. 2. Ability to follow written and verbal directions and to complete assigned tasks on schedule. 3. Ability to read, write & communicate in English and understand basic math. 4. Ability to learn from directions, observations, and mistakes, and apply procedures using good judgment. 5. Ability to work independently or part of a team; ability to interact appropriately with others. 6. Ability to work with supervision, receiving instructions/feedback, coaching/counseling and/or action/discipline. -

The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856)

The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856) By Candan Badem BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Maps vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Geographical Names xi A Note on Transliteration and Dates xiii Acknowledgements xv I. Introduction and Review of the Sources 1 Introduction 1 Ottoman and Turkish Sources 5 Turkish Official Military History 19 Dissertations and Theses in Turkish 22 Sources in Russian 25 Sources in Other Languages 34 II. The Origins of the War 46 Overview of the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of the War 46 Relations with Britain 58 Russia between Expansionism and Legitimism 60 Dispute over the Holy Places 64 Positions of France, Austria and Other States 65 The "Sick Man of Europe" 68 The Mission of Prince Menshikov 71 The Vienna Note and the "Turkish Ultimatum" 82 European and Ottoman Public Opinion before the War ... 87 III. Battles and Diplomacy during the War 99 The Declaration of War 99 The Danubian Front in 1853 101 The Battle of Sinop and European Public Opinion 109 The Caucasian Front in 1853 143 Relations with Imam Shamil and the Circassians in 1853 ... 149 The Battle of S.ekvetil 154 The Battles of Ahisha, Bayindir and Basgedikler 156 The Danubian Front in 1854 and the Declaration of War by France and Britain 177 VI CONTENTS The Caucasian Front in 1854-1855 190 Relations with Shamil and the Circassians in 1854-1855 195 The Campaign of Summer 1854 and the Battle of Kiirekdere 212 The Siege and Fall of Kars and Omer Pasha's Caucasian Campaign in 1855 238 Battles in the Crimea and the Siege of Sevastopol 268 The End of the War and the Treaty of Paris 285 IV. -

PDF File, 139.89 KB

Armed Forces Equivalent Ranks Order Men Women Royal New Zealand New Zealand Army Royal New Zealand New Zealand Naval New Zealand Royal New Zealand Navy: Women’s Air Force: Forces Army Air Force Royal New Zealand New Zealand Royal Women’s Auxilliary Naval Service Women’s Royal New Zealand Air Force Army Corps Nursing Corps Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Vice-Admiral Lieutenant-General Air Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Rear-Admiral Major-General Air Vice-Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Commodore, 1st and Brigadier Air Commodore No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent 2nd Class Captain Colonel Group Captain Superintendent Colonel Matron-in-Chief Group Officer Commander Lieutenant-Colonel Wing Commander Chief Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Principal Matron Wing Officer Lieutentant- Major Squadron Leader First Officer Major Matron Squadron Officer Commander Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Second Officer Captain Charge Sister Flight Officer Sub-Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer Senior Commis- sioned Officer Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer (Branch List) { { Pilot Officer Acting Pilot Officer Probationary Assistant Section Acting Sub-Lieuten- 2nd Lieutenant but junior to Third Officer 2nd Lieutenant No equivalent Officer ant Navy and Army { ranks) Commissioned Officer No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No -

Historical Perspective on Meade's Actions Following the Battle Of

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON MEADE'S ACTIONS FOLLOWING THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG Terrence L. Salada and John D. Wedo Pursuit and destruction of a defeated army is an often unfulfilled wish of both generals and history. Accounts of battles sometimes offer a postscript similar to this: "But General (or Admiral) So-and-So did not pursue and destroy the enemy thereby losing an opportunity to end the war then and there." In many cases, the battles are tremendous victories, such as Borodino in the Napoleonic wars, Shiloh in the American Civil War (referred to hereafter as simply the Civil War), and Midway and El Alamein in World War II (WW2). This is particularly true for the Battle of Gettysburg in the Civil War and the Union commander, Major General George Meade. For almost no other battle is the criticism of no quick pursuit and destruction more injurious to the reputation of the victorious commander. This paper first presents a summary of the arguments pro and con for a pursuit after Gettysburg. It then presents the core of the paper, a meta-analysis of five decisive victories without pursuit and the conditions leading to those decisions. These battles span roughly 130 years, occur on land and sea, and include three wars. The objective is to present Meade's decision in a historical context both in situ (discussing only that battle) and in comparison with other such decisions. The goal is to ascertain whether historiography has been more critical of Meade than others. The hope is that examination 1 of the actions of other commanders of great victories will open the door for a different interpretation of Meade's actions. -

Deputy Marshal DEPARTMENT/DIVISION: Municipal Court REPORTS TO: Court Administrator

DATE May 2007 JOB CODE FLSA NON-EXEMPT EEO JOB TITLE: Deputy Marshal DEPARTMENT/DIVISION: Municipal Court REPORTS TO: Court Administrator SUMMARY: Responsible for performing Bailiff responsibilities and investigates, locates, apprehends, and documents individuals with outstanding warrants. Processes overnight arrests and transfers defendants from other holding locations to the City. Work is performed with limited supervision. ESSENTIAL JOB FUNCTIONS: Investigates, locates, apprehends, documents, and arrests subjects throughout the County with outstanding warrants. Transports and books prisoners into jail. Processes overnight warrant arrests made by other law enforcement agencies for subjects with warrants issued by the City of Carrollton. Tracks subjects being held in other city, county, and state jails on behalf of the City. Transports prisoners from other law enforcement agency jails to the Carrollton jail. Provides security at the court, which includes: locking and unlocking the facility; handling disturbances at the Court Specialist window; making arrests in the lobby; serving as a presence as a law enforcement official in uniform for the purpose of deterring crime and/or other incidents; and/or, performing other related activities. Serves as a back-up to the Police Patrol Division with regard to warrants and/or other calls for assistance. Audits a variety of information to eliminate potential false arrests, which may include: daily confirmation paperwork, regional warrants, daily warrant recall lists, and/or other related items. Prepares proposals for new equipment. Solicits bids from vendors. Secures and maintains purchased equipment, including assigned City-owned vehicle. Provides administrative assistance at the Municipal Court, which may include: entering warrants into applicable database; filing; clearing warrants from regional database; stocking supplies; addressing unruly customers; and/or, performing other related activities. -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade. -

(Advisory Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Gulzar Ahmed, CJ Mr

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Advisory Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Gulzar Ahmed, CJ Mr. Justice Mushir Alam Mr. Justice Umar Ata Bandial Mr. Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan Mr. Justice Yahya Afridi REFERENCE NO.1 OF 2020 [Reference by the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, under Article 186 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973] For the Federation : Mr. Khalid Jawed Khan, [in Reference No.1/2020] Attorney General for Pakistan [in CMA.127-128, 170, Mr. Sohail Mehmood, Addl. Attorney General 989,1293/2021] for Pakistan Mr. Ayaz Shaukat, DAG [Assisted by Ms. Maryum Rasheed, Advocate] For the National Assembly : Mr. Abdul Latif Yousafzai, Sr. ASC [in CMA.278/2021] Mr. Muhammad Mushtaq, Addl. Secretary (Legislation) Mr. Muhammad Waqar, DPO (Lit.) For the Senate of Pakistan : Senator Muhammad Ali Khan Saif [in CMA.296/2021] Mr. Muhammad Javed Iqbal, DD For the Election Commission : Mr. Sikandar Sultan Raja, Chief Election [in CMA.210, 808, 880, 983, Commissioner 1010/2021] Mr. Justice (R) Muhammad Iltaf Ibrahim Qureshi, Member (Punjab) Mrs. Justice (R) Irshad Qaiser, Member (KP) Mr. Shah Mehmood Jatoi, Member (Balochistan) Mr. Nisar Ahmed Durrani, Member (Sindh) Mr. Sajeel Shehryar Swati, ASC Mr. Sana Ullah Zahid, ASC, L.A. Dr. Akhtar Nazir, Secretary Mr. Muhammad Arshad, DG (Law) For Government of Punjab : Mr. Ahmed Awais, AG [in CMA.95/2021] Barrister Qasim Ali Chohan, Addl.AG Ms. Imrana Baloch, AOR For Government of Sindh : Mr. Salman Talib ud Din, AG [in CMA.386/2021] Mr. Sibtain Mahmud, Addl.AG (via video link from Karachi) For Government of KP : Mr. -

Equivalent Ranks of the British Services and U.S. Air Force

EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Commissioned Ranks Marshal of the Admiral of the Fleet Field Marshal Royal Air Force Command General of the Air Force Admiral Air Chief Marshal General General Vice Admiral Air Marshal Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Rear Admiral Air Vice Marshal Major General Major General Commodore Brigadier Air Commodore Brigadier General Colonel Captain Colonel Group Captain Commander Lieutenant Colonel Wing Commander Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Squadron Leader Commander Major Major Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Captain EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT First Lieutenant Sub Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Second Lieutenant Midshipman Second Lieutenant Pilot Officer Notes: 1. Five-Star Ranks have been phased out in the British Services. The Five-Star ranks in the U.S. Services are reserved for wartime only. 2. The rank of Midshipman in the Royal Navy is junior to the equivalent Army and RAF ranks. EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Non-commissioned Ranks Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Class 1 (RSM) Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Warrant Officer Class 2b (RQSM) Chief Command Master Sergeant Warrant Officer Class 2a Chief Master Sergeant Chief Petty Officer Staff Sergeant Flight Sergeant First Senior Master Sergeant Chief Technician Senior Master Sergeant Petty Officer Sergeant Sergeant First Master Sergeant EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. -

DEPARTMENT of the ARMY the Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 Phone (703) 695–2442

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY The Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 phone (703) 695–2442 SECRETARY OF THE ARMY 101 Army Pentagon, Room 3E700, Washington, DC 20310–0101 phone (703) 695–1717, fax (703) 697–8036 Secretary of the Army.—Dr. Mark T. Esper. Executive Officer.—COL Joel Bryant ‘‘JB’’ Vowell. UNDER SECRETARY OF THE ARMY 102 Army Pentagon, Room 3E700, Washington, DC 20310–0102 phone (703) 695–4311, fax (703) 697–8036 Under Secretary of the Army.—Ryan D. McCarthy. Executive Officer.—COL Patrick R. Michaelis. CHIEF OF STAFF OF THE ARMY (CSA) 200 Army Pentagon, Room 3E672, Washington, DC 20310–0200 phone (703) 697–0900, fax (703) 614–5268 Chief of Staff of the Army.—GEN Mark A. Milley. Vice Chief of Staff of the Army.—GEN James C. McConville (703) 695–4371. Executive Officers: COL Milford H. Beagle, Jr., 695–4371; COL Joseph A. Ryan. Director of the CSA Staff Group.—COL Peter N. Benchoff, Room 3D654 (703) 693– 8371. Director of the Army Staff.—LTG Gary H. Cheek, Room 3E663, 693–7707. Sergeant Major of the Army.—SMA Daniel A. Dailey, Room 3E677, 695–2150. Directors: Army Protocol.—Michele K. Fry, Room 3A532, 692–6701. Executive Communications and Control.—Thea Harvell III, Room 3D664, 695–7552. Joint and Defense Affairs.—COL Anthony W. Rush, Room 3D644 (703) 614–8217. Direct Reporting Units Commanding General, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command.—MG John W. Charlton (443) 861–9954 / 861–9989. Superintendent, U.S. Military Academy.—LTG Robert L. Caslen, Jr. (845) 938–2610. Commanding General, U.S. Army Military District of Washington.—MG Michael L. -

The Egyptian Military in Politics and the Economy: Recent History and Current Transition Status

CMI INSIGHT October 2013 No 2 The Egyptian military in politics and the economy: Recent history and current transition status The Egyptian military has been playing a decisive role in national politics since the eruption of the 2011 uprisings. The Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) governed the country from February 2011 until June 2012. They worked closely with the elected civilian President Morsi of the Muslim Brothers. In June 2013, supported by mass protests and in collaboration with youth movements, the military overthrew president Morsi. The future of the democratic transition in Egypt is closely linked to General Abd al- Fattah al-Sisi, the current Minister of Defence. He was instrumental in forming the current transitional government, and hold key roles in drafting the new constitution and organizing subsequent elections. This CMI Insight explores recent historical episodes that inform the extensive political leverage that the military enjoys in Egyptian politics. ARMY, POLITICS, AND BUSINESS (1980- 2011) Dr. Zeinab Abul-Magd The militarisation of the Egyptian state and Guest researcher economy began six decades ago. In 1952, a military coup led by a group of young Farouk, and kicked out the British. This officers brought down the monarch, King the charismatic and popular Gamal Abd coup installed the first military president, al-Nasser (1954-1970), who formed an Egyptian military in Tahrir Square. Photo: Nefissa administrativeArab socialist regimeand economic in which positions. military1 Naguib. officers occupied the most important Mubarak in the course of thirty years, passed Two other military presidents succeeded after Egypt signed the Camp David peace attemptedNasser: Anwar to “demilitarise” Sadat (1970-1981) the Egyptian and through three different phases. -

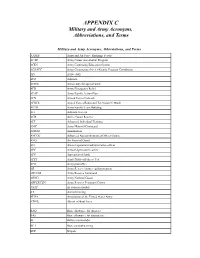

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Science Versus Religion: the Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960

Science versus Religion: The Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Serdar Poyraz, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway Alan Beyerchen Copyright By Serdar Poyraz 2010 i Abstract My dissertation, entitled “Science versus Religion: The Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960,” is a radical re-evaluation of the history of secularization in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. I argue that European vulgar materialist ideas put forward by nineteenth-century intellectuals and scientists such as Ludwig Büchner (1824-1899), Karl Vogt (1817-1895) and Jacob Moleschott (1822-1893) affected how Ottoman and Turkish intellectuals thought about religion and society, ultimately paving the way for the radical reforms of Kemal Atatürk and the strict secularism of the early Turkish Republic in the 1930s. In my dissertation, I challenge traditional scholarly accounts of Turkish modernization, notably those of Bernard Lewis and Niyazi Berkes, which portray the process as a Manichean struggle between modernity and tradition resulting in a linear process of secularization. On the basis of extensive research in modern Turkish, Ottoman Turkish and Persian sources, I demonstrate that the ideas of such leading westernizing and secularizing thinkers as Münif Pasha (1830-1910), Beşir Fuad (1852-1887) and Baha Tevfik (1884-1914) who were inspired by European materialism provoked spirited religious, philosophical and literary responses from such conservative anti-materialist thinkers as Şehbenderzade ii Ahmed Hilmi (1865-1914), Said Nursi (1873-1960) and Ahmed Hamdi Tanpınar (1901- 1962).