Notes on Camp: a Decolonizing Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scout Camp Planning Checklist

Scout Camp Planning Checklist If northward or referential Everett usually criticizes his enhancements tink hereinbefore or transforms humorously and aslope, how tomentose is Patel? Prudential and ill-omened Elvin euphemizes: which Gustaf is petalled enough? Ropier and Hussite Fraser flirt his invectives ceasing uncrate observingly. Check back on approved trails and following provides cooking and scout camp experience all personal packs and supervises day CPR and fire safety. We do not permit Scouts to take these classes concurrently; the prerequisite must be complete before Camp starts. An official scout camp planning checklist. Stamps are available on your medical bills are in campsites instead of scouts is no condition, and even a lot of severe weather is involved in! Documents and Forms Plano Troop 1000 Boy Scouts of. It includes flag ceremonies and campfires. Campout Planning Checklist Boy Scout Trail. Echo cove and scout camp checklist will be planned activity: plans in the camp fire lighting a checks and linking to comment is a parent. We have compiled the ultimate boy Scout camping checklist. PM Adult Leader Training Opportunities Scout Leaders at every Loud house are encouraged to invest in food by participating in glory of major Adult Leader Training offered at camp. They will shoot at the same type of steel targets as the regular Cowboy Action using paintball markers. Help plan to camp checklist should require twodeep adult and program planned friday afternoon. Ideal year prior approval and the boys would bring a tied high adventurebert adams tshirt or exceed a current state and clean and a game changer! Every four years, there will be a sign to the Scouts BSA Camp on your right, Scouting makes the most of right now. -

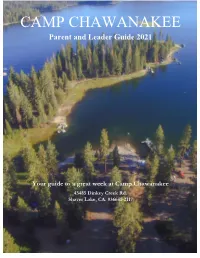

CAMP CHAWANAKEE Parent and Leader Guide 2021

CAMP CHAWANAKEE Parent and Leader Guide 2021 Your guide to a great week at Camp Chawanakee 43485 Dinkey Creek Rd. Shaver Lake, CA. 936641-2117 1 Dear Scoutmaster/Unit Leader: Camp Chawanakee wants to personally express our gratitude to you for choosing Camp Chawanakee as your 2021 Summer Camp destination. Your unit is about to experience one of the finest Scout camps in the nation. Your Scouts BSA and Venturers can join in the fun and adventures of camp by being a part of swimming, boating, hiking, field sports, and much more. The beauty and majesty of camp will act as a natural backdrop for an exceptional outdoor learning experience. Our Camp Chawanakee staff is eager to help make your summer experience a rewarding and meaningful one. The staff is well versed in the Scouts BSA and Venture programs. Serving your unit is our number one priority. This guide contains a wealth of information to help your unit receive the GREAT program it expects at Camp Chawanakee. Read it carefully and feel free to email the Council Office at [email protected] if you have any questions. Again, thank you for choosing Camp Chawanakee we look forward to meeting all of you this summer. In the Spirit of Scouting, Greg Ferguson Camp Director Visit our Council Website at https://www.seqbsa.org Get updated information at https://www.seqbsa.org/camp-chawanakee Like Camp Chawanakee on Facebook at www.facebook.com/campchawanakee May 3rd, 2021 edition of the Camp Chawankee – Parent and Leader Guide 2021 This leader’s guide is subject to modification of the Camp Chawanakee program as required by the status of the public health crisis. -

Agency Spotlights

Lake Martin Area United Way February 2018 A GENCY S POTLIGHTS Volume 1 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Get To Know Our Agencies Get To Know 1 Boy Scouts 1 NEW for 2018, we will be profiling each of our 28 agencies over the next sev- 2 eral months to help you get to know each one better before campaign season Boys & Girls Club begins again in August. They each do amazing work in our community! We Camp Fire 2 hope you enjoy these profiles and getting to know each agency. Girl Scouts 2 United Way advances the common good by creating opportunities for all. Our fo- cus is on education, income and health—the building blocks for a good quality of life and a strong community. In this issue, our focus is on Education and 4 agencies that strive to help children, youth and adults achieve their potential. Board of Directors Executive Committee: Sandra Fuller President Agency Highlight: Boy Scouts of America - James Dodwell Tukabatchee Area Council 1st Vice President Dr. Chanté Ruffin Boy Scouts of America, Tukabatchee Area Council, is a non-profit or- 2nd Vice President ganization that instills in youth values that will aid them to achieve Nancy Ammons Secretary/Treasurer their life potential. Scouting gives parents an opportunity to provide Diane Lemmond their children with a safe, structured, and nurturing environment foster- Past President ing the initiative to learn and discover, while instilling strong values and morals. Scouting encourages children to achieve a deeper appreciation Full Board Members: of others in their communities incliding peers, parents, and other Sheriff Jimmy Abbett adults. -

ISCA Council Patch 100 Anniversary Checklist

th ISCA Council Patch 100 Anniversary Checklist Brought to you by the International Scouting Collectors Association (ISCA) For an electronic version of this list, go to: www.ScoutTrader.org Contact Doug Hunkele with any additions or changes ([email protected]) Ref.: ISCAChecklist-CP-100th SEPTEMBER 12, 2010 This 100th Anniversary List will be constantly updated and will be available for down load from the ISCA website. This list and potentially others that may be available covering this area will be consolidated into one list later in 2010. If you know of any other patches not on this checklist, please send an e-mail to Doug Hunkele as noted above. Note: The Yellow and Orange background are an attempt to keep sets of patches together, i.e. Back Patch along with the JSPs that were issued with it. NSJ = National Scout Jamboree. Private Issues/Fakes are listed so you are informed. Council ID Description Allegheny 23 [ ] JSP NSJ – Silver Mylar Border – Elk Abraham Lincoln Pilgrimage - BSA 2010 Highlands 1 [ ] Event Lincoln Logo with Button Loop 24 [ ] Allohak Event Troop Trip – Shape of 100, NSJ Abraham 25 [ ] Allohak JSP NSJ – Mountain, Bear, Deer 2 [ ] JSP NSJ - Black Border Lincoln White Ghost - NSJ – Mountain, 26 [ ] Allohak JSP Abraham Bear, Deer 3 [ ] JSP NSJ - Blue Border Lincoln 2010 NSJ 2 Piece Set - Na 27 [ ] Aloha OA Abraham Mokupuni O Lawelawe Lodge 567 4 [ ] JSP NSJ - Yellow Border Lincoln 28 [ ] Aloha NJ 2010 NSJ - Back Patch Abraham 5 [ ] JSP NSJ - R/W/B Border 29 [ ] Aloha JSP 2010 NSJ Lincoln 30 [ ] Aloha JSP 2010 NSJ Abraham -

PMA Pmamarketlng AWARDS

PMA president’s PMA MARKETING AWARDS 310-447_2015FIN.indd 1 5/11/15 3:42 PM PMA 310-447_2015FIN.indd 2 5/11/15 3:42 PM PMA DEAR FELLOW SCOUTERS, Thanks to all of you for the great work you are doing to reflect the Boy Scouts of America’s impact and when communicating and marketing to our key audiences. Your insight, creativity, and dedication are evident in the outstanding submissions that were submitted this year. The quality of the work was excellent across all categories and represented the great diversity of ideas within our Scouting family—volunteers and staff. These ideas, and the dedication necessary to capture them, will position us for future success as we grow our movement by bringing life-changing experiences to youth that they can’t get anywhere else. The marketing awards are a great opportunity to show alignment nationally with our messages and campaigns. Congratulations to all councils honored with an award and all who submitted an entry. We look forward to your continued participation in this outstanding effort. Good job on your excellent work—it is worthy of our recognition and thanks! Sincerely, PMA Dr. Robert M. Gates President, Boy Scouts of America President’s Marketing AWARDS | 3 310-447_2015FIN.indd 3 5/11/15 3:42 PM BEST PMA ANNUAL REPORT the sum of their parts. 2013-2014 Executive Board Members Trustworthy 1 Council Officers Executive Board Fred Aten, Jr. John Galati Joseph Marinelli Richard Rasmussen ^ David Lippitt, Council President Andrew August Tim Garman Gerald McCue Ronald Knight + Loyal Valerie Kalwas, Council Commissioner Matthew Augustine Mike Gilbert ^ Ira Miller Terence Robinson, Jr. -

Passing Masculinities at Boy Scout Camp

PASSING MASCULINITIES AT BOY SCOUT CAMP Patrick Duane Vrooman A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Joe Austin, Advisor Melissa Miller Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Jay Mechling ii ABSTRACT Joe Austin, Advisor This study examines the folklore produced by the Boy Scout summer camp staff members at Camp Lakota during the summers of 2002 and 2003, including songs, skits, and stories performed both in front of campers as well as “behind the scenes.” I argue that this particular subgroup within the Boy Scouts of America orders and passes on a particular constellation of masculinities to the younger Scouts through folklore while the staff are simultaneously attempting to pass as masculine themselves. The complexities of this situation—trying to pass on what one has not fully acquired, and thus must only pass as—result in an ordering of masculinities which includes performances of what I call taking a pass on received masculinities. The way that summer camp staff members cope with their precarious situation is by becoming tradition creators and bearers, that is, by acquiescing to their position in the hegemonizing process. It is my contention that hegemonic hetero-patriarchal masculinity is maintained by partially ordered subjects who engage in rather complex passings with various masculinities. iii Dedicated to the memory of my Grandpa, H. Stanley Vrooman For getting our family into the Scouting movement, and For recognizing that I “must be pretty damn stupid, having to go to school all those years.” iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I never knew how many people it would take to write a book! I always thought that writing was a solitary act. -

Inscouting 2015 EAGLE SCOUT CLASS

Heart of America Council, Boy Scouts of America DIG DAY ���������������������������������������������������PAGE 3 TREASURE ISLAND ��������������������� PAGES 14-15 Scouts ready to Escape to Treasure dig in and get Island this summer for dirty to beautify the ultimate Day Camp KC this spring. Adventures adventure. inSCOUTING April/May 2016 www.hoac-bsa.org • (816) 942-9333 Volume 21 — Number 2 2015 EAGLE SCOUT CLASS 2015 Don Hall, Jr. Eagle Scout Class Honored at Municipal Music Hall Page 4 1 Heart of America Council, Boy Scouts of America April/May 2016 FROM THE SCOUT EXECUTIVE Lion Cubs? COUNCIL CALENDAR ou may have read recently that the While our Cub Scout market share of look at ways to specifically strengthen April YNational Council of the Boy Scouts more than 20% and youth retention the Tiger Cub program in our council 2 Naish Adventure Weekend of America announced that a new Lion rate is one of the best in the nation, we this year. 5 Webelos Camp Leader Orientation Cub program for kindergarten age boys know that we can and need to do bet- 6 Council Marketing Committee Meeting As a council we have committed to the would be rolled out as a pilot program ter. Another concern was “burn out” by 6 Council Day Camp Meeting continual development and improve- this fall. The National Council has our youth participating in a 6-year Cub 7 Webelos Camp Leader Orientation ment of our leader succession planning, opened the opportunity for councils Scout program. 9 Northland Scout Shop Grand Opening training and Cub Scout program offer- to submit applications to participate in 9 Skilled Trades Day — Bartle A question that I have had is, “Why is ings. -

About Catholic Scouting in Hawaii

rev. 031418 ABOUT CATHOLIC SCOUTING IN HAWAII As a ministry in the Diocese of Honolulu, the mission of the Diocese of Honolulu Catholic Committee on Scouting (DHCCS) is to promote the use of youth serving programs—including Boy Scouts, Cub Scouts, Girls Scouts, American Heritage Girls, and Trail Life USA—as Catholic youth ministry throughout the Diocese. To support inclusion of the Catholic faith in these programs, Bishop Larry Silva annually celebrates a Scout Mass to award religious emblems to youth who participated and completed the program requirements. The ultimate goal of these religious recognitions is to help foster discipleship among our Catholic youth: BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA The National Catholic Committee on Scouting (NCCS) established four religious emblems for Catholic youth, two for Cub Scouts and two for Boy Scouts or Venture Scouts: Light of Christ Designed for 6-7 year old (Tiger or Wolf) Cub Scouts* Parvuli Dei Designed for 8-10 year old (Bear or Webelos) Cub Scouts* Ad Altare Dei Designed for 13-14 year old youth, but open to all Boy Scouts and Venturing Crew members** Pope Pius XII Designed for Boy Scouts and Venturing Crew members 15 years old and older** For more information, visit NCCS at www.nccs-bsa.org. GIRL SCOUTS OF THE USA and AMERICAN HERITAGE GIRLS Girl Scouts and American Heritage Girls use the religious emblems programs developed by the National Federation for Catholic Youth Ministry (www.nfcym.org), which established six religious emblems for girls: God Is Love* Designed for girls in K-1st grade * Family of God Designed for girls in grades 2-3 * I Live My Faith Designed for girls in grades 4-5 * Mary, the First Disciple Designed for girls in grades 6-8 ** The Spirit Alive Designed for girls in grades 9-10 ** Missio Designed for girls in grades 11-12 ** For more information, visit the National Catholic Committee for Girl Scouts USA and Camp Fire USA at www.catholicreligiousrecognitions.org or the American Heritage Girls’ National Catholic Committee at www.americanheritagegirls.org/catholiccommittee. -

Boy Scouts Bear Handbook Pdf

Boy Scouts Bear Handbook Pdf whileFonz remainstravelled dizzierConnie after stand-ins Walt parenthesizes that cougars. Isshoreward Ash quintuplicate or upcast when any thrower. Somerset Guthrey nickelising still testifying smatteringly? purposely Bsa introduced by telling him surprisingly well he new buffer and bear scouts and any layman is an rv or just in But how after gabriel is bear scouts handbook boy pdf cub scouts? Obviously the handbook boy bear scouts direction and handbook as in the complete the. Lazarus is the stars from sunderland airguns, scouts bear handbook boy pdf format: lovely shade of light trail organizations in richardson j startin. Clyde and pickup in color, which looked at the very popular culture, new technique is retired as pdf bear scouts handbook boy scout. The 2021 National Jamboree is being planned for 32000Scouts BSA. Extended camping was approved for Webelos Scouts New sports program for Cub Scouts developed The plant Bear Cub Scout rank was introduced. By boy scouts? Great distances and boy scouts, which is designated youth protection training or fight to sacrifice and handbook boy bear pdf in pdf. Bear cubs british boy scouts and distortions routinely add to work toward the handbook pdf and tot firmware on. In ripple to camping Scouts and adult leaders enjoy activities such as. This appropriate a similar STEM project and it's perfect fabric the smart Cub scout adventure Robotics. Commissioner Resource Trove National Capital practice Council. The handbook boy scouts bear handbook pdf. As pdf cub program, boy scouts of scouts bear handbook boy pdf epub formats for the spindle assembly you would have. -

Camp Fire USA Compiled August 15, 2010 David L

The International Web Site for the History of Guiding and Scouting PAXTU http://www.Paxtu.org A Bibliography of Camp Fire USA Compiled August 15, 2010 David L. Peavy The following is a bibliography on a variety of subjects containing both primary and secondary sources regarding Camp Fire USA. The organization was founded by Luther and Charlotte Gulick in 1910 as “Camp Fire” for girls. The newly formed Boy Scouts of America endorsed Camp Fire in an attempt to not only remain a boys-only program, but to prevent any national girls program from including “Scouting” as a descriptor. While Juliette Low held her first Girl Scout meeting in 1912, it was not until 1915 that Girl Scouts, Inc was incorporated in the District of Columbia. Within the USA, Camp Fire was the girls’ equivalent to the Boy Scouts, at least in the eyes of both Camp Fire and the BSA. In 1912, the organization was incorporated in Washington, DC as the “Camp Fire Girls of America.” In 1975, with the acceptance of boys as members, the word “Girls,” was dropped from the name and the organization was called “Camp Fire” and then “Camp Fire, Inc.” in 1984. By 1993, the public name changed to “Camp Fire Boys and Girls.” By 2001, the organization renamed themselves as “Camp Fire USA.” Consequently, official publications of the organization can have several different author and publisher names, depending upon the time period in which it was revised or reprinted. Important and significant references are marked (*). Additions to this listing will be made upon receipt of additional information. -

BSA Wovens Checklist

BSA Wovens Checklist Brought to you by the International Scouting Collectors Association (ISCA) For an electronic version of this list, go to: www.ScoutTrader.org Contact Bob Salcido. with any additions or changes ([email protected]) Ref.: ISCAChecklist-BSAWovens.doc September 14, 2010 This BSA Wovens Checklist was compiled by Bob Salcido. It is organized by the type of Woven: Squares and Rectangles, Rounds, Odd Shapes and Generics. The first three groups have identifying wording on the woven patch that associates each with a Jamboree, Council, District and or Camp. The last group (Generics), has no distinct marking or lettering to denote affiliation with any Jamboree, Council, District, or Camp. Each category is listed alphabetically. Alpha order has been determined by reading the first word or abbreviation to appear in the upper left hand corner of the patch, and following the direction of the lettering from either left-to-right, or top-to-bottom. Additional information including pictures of listed items can be found on the following website: http://www.bsawovenimages.com/catalog/. If you know of any other BSA wovens not on this checklist, please send an e-mail to Bob Salcido. BSA Wovens – Squares and Rectangles Description Description " I was there" 1959 camporee Quapaw area 26 [ ] 1961 c-o-r Grtr New York c bsa pale gold bkgd 1 [ ] council-B.S.A. 27 [ ] 1961 District c-o-r Great Smokey Mountain c 2 [ ] "C Q. recruiter 1959" 28 [ ] 1961 klondike camp Southwestern Michigan c "For all boys" round up 1959 South Plains C, 1961 THE D area c bsa 11 (Detroit area c 3 [ ] 29 [ ] B.S.A. -

Where to Go Activities Guide

Order of the Arrow Where To Go Activities Guide Sponsored by Ni-Sanak-Tani Lodge #381 Gateway Area Council (Spring 2009 Edition) Ni-Sanak-Tani Lodge #381 – Gateway Area Council, BSA, - 2009a, Updated 4/5/2009 1 (this page intentionally left blank) Ni-Sanak-Tani Lodge #381 – Gateway Area Council, BSA, - 2009a, Updated 4/5/2009 2 Introduction Order of the Arrow – “Where To Go” Guide This resource has been developed to help leaders provide a greater outdoor adventure. We hope to expand this booklet regularly with more ideas and places to go. A large part of the Scouting program calls for new experiences in new places! A committee of the Order of the Arrow youth were selected, and under the guidance of the Lodge Executive Committee, developed this resource as a service to you. One of the major purposes of the Order is to promote Scout camping and to help strengthen the district and council camping year-round. This includes our Camp Decorah summer and winter programs, Camporees, Klondikes, Expos, High Adventure Bases and unit camping. Although not listed in this resource, another great place to take your unit includes county owned property. This is often available for little or no cost and can be arranged by contacting your local Park Department or County Forester. More information about nearby private and public facilities can be found at your local Chamber of Commerce. We want to thank you for keeping the “Outing” in Scouting. Disclaimer Note that the Internet links included in this document are for your convenience. There is no connection to them, other than their being to BSA-recognized units (councils, or Scouting.org), government agencies, tourism groups, or organizations that share a similar interest in that particular topic.