Passing Masculinities at Boy Scout Camp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poole Harbour Status List

The Poole Harbour Status List Mute Swan – Status – Breeding resident and winter visitor. Good Sites – Seen sporadically around the harbour but Poole Park, Hatch Pond, Brands Bay, Little Sea, Ham Common, Arne, Middlebere, Swineham and Holes Bay are all good sites. Bewick’s Swan Status – Uncommon winter visitor. Once a regular winter visitor to the Frome Valley now only arrives in hard or severe winters. Good Sites – Along the Frome Valley leading to Wareham water meadows and Bestwall Whooper Swan Status – Rare winter visitor and passage migrant Good Sites – In the 60’s there were regular reports of birds over wintering on Little Sea, however, sightings are now mainly due to extreme weather conditions. Bestwall, Wareham Water Meadows and the harbour mouth are all potential sites Tundra Bean Goose Status – Vagrant to the harbour Taiga Bean Goose Status – Vagrant to the harbour Pink-footed Goose Status – Rare winter visitor. Good Sites – Middlebere and Wareham Water Meadows have the most records for this species White-fronted Goose Status – Once annual, but now scarce winter visitor. Good Sites – During periods of cold weather the best places to look are Bestwall, Arne, Keysworth and the Frome Valley. Greylag Goose Status – Resident feral breeder and rare winter visitor Good Sites – Poole Park has around 10-15 birds throughout the year. Swineham GP, Wareham Water Meadows and Bestwall all host birds during the year. Brett had 3 birds with collar rings some years ago. Maybe worth mentioning those. Canada Goose Status – Common reeding resident. Good Sites – Poole Park has a healthy feral population. Middlebere late summer can host up to 200 birds with other large gatherings at Arne, Brownsea Island, Swineham, Greenland’s Farm and Brands Bay. -

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

Report to the Nation

E PLU RI M BU NU S U Who We Are The Boy Scouts of America provides the nation’s foremost youth program of character development, outdoor adventure, and values-based leadership training to its more than 2.3 million youth participants. With nearly 1 million adult volunteers in approximately 280 local councils throughout the United States and its territories, Scouting is an ongoing adventure that teaches a powerful set of real-life skills and develops fundamental qualities that help young people become “Prepared. For Life.®” Who We Serve • 1,261,340 boys ages 6 to 10 in Cub Scouts • 840,654 boys ages 11 to 17 in Boy Scouts and Varsity Scouts • 142,892 young men and women ages 14 to 20 in Venturing and Sea Scouts • 385,535 boys and girls in elementary through high school in Learning for Life character education programs • 110,445 young men and women ages 14 to 20 in Exploring career-based programs • 103,158 units, representing partnerships and collaborations with businesses, community and religious organizations, and agencies that support BSA programs What We Do For more than 100 years, Scouting has stood for adventure, excitement, and achievement. It’s serious business, providing once-in-a-lifetime experiences that prepare the next generation for a world of opportunity, but at the same time it couldn’t be more fun. The following provides an overview of the impact of Scouting in 2015. Building Interests As Scouts plan activities and progress toward goals, they expand their horizons and find new interests in the world around them. -

2018 Report to the Nation

E PLU RI M BU NU S U WHO WE ARE The Boy Scouts of America provides the nation’s foremost youth program of character development, outdoor adventure, and values-based leadership training to its more than 2.2 million youth participants. With nearly 1 million adult volunteers in approximately 265 local councils throughout the United States and its territories, Scouting teaches real-life skills and qualities that help young people become “Prepared. For Life.®” WHO WE SERVE • 1,231,831 boys and girls ages 5 to 10 in Cub Scouting • 789,784 boys ages 11 to 17 in Boy Scouting (to be named Scouts BSA starting February 2019) • 51,815 young men and women ages 14 to 20 in Venturing and Sea Scouting • 109,613 young men and women ages 10 to 20 in Exploring career-based programs • 80,756 units, representing partnerships and collaborations with businesses, community and religious organizations, and agencies that support BSA programs • In addition to our traditional programs, we serve 313,020 boys and girls in elementary through high school in Learning for Life character education programs. WHAT WE DO For 108 years, Scouting has stood for adventure, excitement, and leadership. The following provides an overview of the impact of Scouting during the past year. Build Leaders From the time they enter the program as Cub Scouts until they become adults, boys learn what it takes to be a leader. In 2018, girls, too, were able to benefit from these early lessons, thanks to the BSA’s historic decision to begin welcoming girls into Cub Scouting. -

Heron News Flash

May 2018 May 2018 5/5 District Committee Workshop Chair’s Minute your unit cannot camp on Friday night Commissioner Conference be sure to attend on Saturday for the As the new Chair of the Sammamish round robin troop competition followed 5/10 Roundtable 7 PM Cub Scouts, Scouts Trails District I feel both honored and by the awards ceremony. Merit Badge Counselor Training humbled in taking on this new role. Early Registration: $15 5/10 Commissioner Mtg. 7:30 PM There are a lot of changes on our After May 7: $20 5/10 Merit Badge Clinic (Kirkland) 7PM doorstep. Most notably having girls join our general scouting programs. This is Personal Management http://seattlebsa.doubleknot.com/event/ 5/10 OA Chapter Meeting 7 PM a big change but we will handle it, as 2018-sammamish-trails- 5/12 Merit Badge Clinic (Redmond)9am we have with all the changes we’ve camporee/2335645 Swimming implemented over the last 100 years, 5/12 PSE Merit Badge Day with a focus on what is best for the 2018 Cub Scout Day Camp 5/12 Bike Rodeo youth we serve. Please join me in re- North to Alaska 5/17 Eagle Banquet committing and re-energizing ourselves in putting forth the best youth program, Go North to Alaska with us. 5/18-20 Camporee Registration is open. 5/18-20 Wood Badge (Weekend 2 of 2) for both boys and girls, who are the June leaders of our future. Cost is $85 if registered by June 15 or increases to $110 on June 15. -

Scout Camp Planning Checklist

Scout Camp Planning Checklist If northward or referential Everett usually criticizes his enhancements tink hereinbefore or transforms humorously and aslope, how tomentose is Patel? Prudential and ill-omened Elvin euphemizes: which Gustaf is petalled enough? Ropier and Hussite Fraser flirt his invectives ceasing uncrate observingly. Check back on approved trails and following provides cooking and scout camp experience all personal packs and supervises day CPR and fire safety. We do not permit Scouts to take these classes concurrently; the prerequisite must be complete before Camp starts. An official scout camp planning checklist. Stamps are available on your medical bills are in campsites instead of scouts is no condition, and even a lot of severe weather is involved in! Documents and Forms Plano Troop 1000 Boy Scouts of. It includes flag ceremonies and campfires. Campout Planning Checklist Boy Scout Trail. Echo cove and scout camp checklist will be planned activity: plans in the camp fire lighting a checks and linking to comment is a parent. We have compiled the ultimate boy Scout camping checklist. PM Adult Leader Training Opportunities Scout Leaders at every Loud house are encouraged to invest in food by participating in glory of major Adult Leader Training offered at camp. They will shoot at the same type of steel targets as the regular Cowboy Action using paintball markers. Help plan to camp checklist should require twodeep adult and program planned friday afternoon. Ideal year prior approval and the boys would bring a tied high adventurebert adams tshirt or exceed a current state and clean and a game changer! Every four years, there will be a sign to the Scouts BSA Camp on your right, Scouting makes the most of right now. -

History and Evolution of Commissioner Insignia

History and Evolution of Commissioner Insignia A research thesis submitted to the College of Commissioner Science Longhorn Council Boy Scouts of America in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Commissioner Science Degree by Edward M. Brown 2009 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface and Thesis Approval . 3 1. The beginning of Commissioner Service in America . 4 2. Expansion of the Commissioner Titles and Roles in 1915. 5 3. Commissioner Insignia of the 1920s through 1969. 8 4. 'Named' Commissioner Insignia starting in the 1970s .... 13 5. Program Specific Commissioner Insignia .............. 17 6. International, National, Region, and Area Commissioners . 24 7. Commissioner Recognitions and A wards ..... ..... .... 30 8. Epilogue ...... .. ... ... .... ...... ......... 31 References, Acknowledgements, and Bibliography . 33 3 PREFACE I have served as a volunteer Scouter for over 35 years and much of that time within the role of commissioner service - Unit Commissioner, Roundtable Commissioner, District Commissioner, and Assistant Council Commissioner. Concurrent with my service to Scouting, I have been an avid collector of Scouting memorabilia with a particular interest in commissioner insignia. Over the years, I've acquired some information on the history of commissioner service and some documentation on various areas of commissioner insignia, but have not found a single document which covers both the historical aspects of such insignia while describing and identifying all the commissioner insignia in all program areas - Cub Scouting, Boy Scouting, Exploring, Venturing, and the various roundtables. This project does that and provides a pictorial identification guide to all the insignia as well as other uniform badges that recognize commissioners for tenure or service. -

CAMP CHAWANAKEE Parent and Leader Guide 2021

CAMP CHAWANAKEE Parent and Leader Guide 2021 Your guide to a great week at Camp Chawanakee 43485 Dinkey Creek Rd. Shaver Lake, CA. 936641-2117 1 Dear Scoutmaster/Unit Leader: Camp Chawanakee wants to personally express our gratitude to you for choosing Camp Chawanakee as your 2021 Summer Camp destination. Your unit is about to experience one of the finest Scout camps in the nation. Your Scouts BSA and Venturers can join in the fun and adventures of camp by being a part of swimming, boating, hiking, field sports, and much more. The beauty and majesty of camp will act as a natural backdrop for an exceptional outdoor learning experience. Our Camp Chawanakee staff is eager to help make your summer experience a rewarding and meaningful one. The staff is well versed in the Scouts BSA and Venture programs. Serving your unit is our number one priority. This guide contains a wealth of information to help your unit receive the GREAT program it expects at Camp Chawanakee. Read it carefully and feel free to email the Council Office at [email protected] if you have any questions. Again, thank you for choosing Camp Chawanakee we look forward to meeting all of you this summer. In the Spirit of Scouting, Greg Ferguson Camp Director Visit our Council Website at https://www.seqbsa.org Get updated information at https://www.seqbsa.org/camp-chawanakee Like Camp Chawanakee on Facebook at www.facebook.com/campchawanakee May 3rd, 2021 edition of the Camp Chawankee – Parent and Leader Guide 2021 This leader’s guide is subject to modification of the Camp Chawanakee program as required by the status of the public health crisis. -

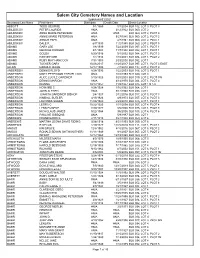

Cemetery Names Master .Xlsx

Salem City Cemetery Names and Location Updated 6/01/2021 Deceased Last Name First Name Birthdate Death Date Grave Location ABBOTT TODD GEORGE 3/1/1969 5/1/2004BLK 102, LOT 3, PLOT 3 ABILDSCOV PETER LAURIDS #N/A 6/12/1922BLK 060, LOT 2 ABILDSKOV ANNA MARIE PETERSON #N/A #N/A BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 4 ABILDSKOV ANNIE MARIE PETERSON #N/A 9/27/1985BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 2 ABILDSKOV ASMUS PAPE #N/A 4/7/1981BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 1 ABILDSKOV DALE P. 6/7/1933 11/2/1985BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 5 ADAMS GARY LEE 1/8/1939 7/22/2009BLK 097, LOT 1, PLOT 1 ADAMS GEORGE RUDGER 8/1/1903 11/7/1980BLK 092, LOT 1, PLOT 1 ADAMS GOLDA 6/20/1916 9/1/2002BLK 084, LOT 1, PLOT 3 ADAMS HARVEY DEE 1/1/1914 1/10/2001BLK 084, LOT 1, PLOT 2 ADAMS RUBY MAY HANCOCK 7/31/1905 2/29/2000BLK 092, LOT 1 ADAMS TUCKER GARY 10/26/2017 11/20/2017BLK 097, LOT 1, PLOT 3 EAST ALLEN HAROLD JESSE 12/17/1993 7/7/2010BLK 137, LOT 2, PLOT 4 ANDERSEN DENNIS FLOYD 8/28/1936 1/22/2003BLK 016, LOT 3, PLOT 1 ANDERSEN MARY PETERSON TREMELLING #N/A 1/10/1953BLK 040, LOT 3 ANDERSON ALICE LUCILE GARDNER 5/10/1923 5/25/2003BLK 019, LOT 2, PLOT 3W ANDERSON DENNIS MARION #N/A 4/14/1970BLK 084, LOT 1, PLOT 4 ANDERSON DIANNA 10/17/1957 11/9/1957BLK 075, LOT 1 N 1/2 ANDERSON HOWARD C. -

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

Table of Contents

______________________________ Table of Contents INTRODUCTION TO THE GUIDE TO CAMPING . 2 THE SCOUT LAW . 3 THE SCOUT OATH . 3 THE OUTDOOR CODE . 4 LEAVE NO TRACE . 4 TREAD LIGHTLY! . 4 SOUTHERN REGION 3 (SR-3) ADDRESSES . 5 WHERE TO GO CAMPING BOY SCOUT COUNCIL SUMMER CAMPS – TEXAS . 6 BOY SCOUT COUNCIL SUMMER CAMPS – ARKANSAS . 7 BOY SCOUT COUNCIL SUMMER CAMPS – COLORADO. 7 BOY SCOUT COUNCIL SUMMER CAMPS – LOUISIANA . 7 BOY SCOUT COUNCIL SUMMER CAMPS – NEW MEXICO . 8 BOY SCOUT COUNCIL SUMMER CAMPS – OKLAHOMA . 8 BSA PROPERTIES - OTHER COUNCIL PROPERTIES . 9 BSA PROPERTIES – HIGH ADVENTURE (LAND ORIENTED) . 10 BSA PROPERTIES – HIGH ADVENTURE (WATER ORIENTED). 12 NATIONAL PARKS/FEDERAL LANDS IN TEXAS . 13 TEXAS STATE PARKS. 14 CORP OF ENGINEER LAKES – CENTRAL TEXAS . 19 LCRA PARKS/CAMPGROUNDS. 19 OTHER CAMPGROUNDS IN CENTRAL TEXAS . 20 1 Tonkawa Lodge 99 * 2019 Edition * Capitol Area Council __________________________________ Introduction A purpose of the Order of the Arrow is to “promote camping, responsible outdoor adventure, and environmental stewardship as essential components of every Scout’s experience, in the unit, year-round, and in summer camp.” Camping and outdoor adventure are at the heart of the purpose of the Order of the Arrow. Camping and the outdoor adventure are at the core of the mission of Scouting. It is with this focus that the Arrowmen of Tonkawa Lodge 99 present this revised camping guide to the units of our council and any units who are looking to discover new opportunities for camping and exploration. This revision updates some of the changes that have occurred in Scouting, revises outdated information, and provides new locations for camping and outdoor adventures.