Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POST OFFICE Dorsetsidttf • • FARMERS-Continued

POST OFFICE DORSETSIDttf • • FARMERS-continued. Stick land Mrs. J. Keysworth~ Wareham Taylor T. Alweston~ Folk, Sherborne Senior 0. Hinton St. Mary, Blandford Stickland T. East Burton, Dorchester Taylor V. Ash more, Ludwell 6enio.f T. Marnhull, Dlar.dfotd Stone D. llurton Brad stock, Bridport Taylor W. Whitchurcb, Bridport Senror W. Hinton St. l\fary~ Blandforlt Stone D. J. Walditch, Bridport Tett G.'Cheselhourne, Dorchester SeymerJ. Wool, Wareham Stone H. Weston, Portland · Tett J. Milton Abbas,Blandford Seymour A~ Hinton St. Mar,r,Blandford Stone J. Wyke Reg-is Thomas W. Cbarmin8ter, Dorcbester SeymourJ. Church st. Lyme Regis Stone J. Hillfield, Cerne Thomas W. Drimptom, Beaminster Seymour R. Bradpole, l3ridport Stone J. Walditch, Bridport Thompson T. Bluntsmoor, :Mosterton, SeymonrSeth,LittleMoors,Hampreston, Stone R. Bedcister, Shaftesbury Crewkerne Wimborne Stone Mrs.S.Burton Brad stock, Bridpoft Tink N. Monckton-up-Wimbornel Cran• Sharp E. Manston, Blandford Stone T. Stower Provost, Bla.ndford borne Sharp J. Motcombe, Shaftesbury Stone T. Hillfield, Cerne Tolly R. r.rosterton, Crewkernc Shepard ll~ R. Wimbome St. Giles, Stone T. Shipton Gorg-e, Bridport Tomkins .Mrs. M. Rampisham 2 Dor~ Cranborne Stone T. Yetminster, Sberborne chester Shepard J. T. Ansfy, Dorchestet Stone T. jun. Stower Provost, BlandCord Tomkins T. Piddletrenthide, Dorcl1ester Sllepherd Mrs. A. Catti!ltock, Dorchestr Stone T. L. South well, Portland Tomkins W. Rampi~ham, Dorchester Shepherd E. H. Wool, Wareham Stone W. Fiddleford, Blandford Toms J. Nether Compton, Sherborne Shepplltd W. Gillingham, Bath Stone W. Gillingham, Bath Toogood J. Alweston, Folk, Sherborne Sherren J. West Knigbton, Dorclwster Stone W. Weston, Portland Toomer R. Bere Regis, Blandford Sherren J. -

West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015 Policies Maps

West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan Policies Maps - Background Document 2015 Local Plan Policies Maps: background document West Dorset, Weymouth and Portland Local Plan Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 WEST DORSET DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL DESCRIPTIONS BY SETTLEMENT BEAMINSTER ................................................................................................................................... 3 BISHOP’S CAUNDLE ......................................................................................................................... 3 BRADFORD ABBAS .......................................................................................................................... 4 BRIDPORT and WEST BAY, ALLINGTON, BOTHENHAMPTON, BRADPOLE and WALDITCH ............ 4 BROADMAYNE and WEST KNIGHTON ............................................................................................ 4 BROADWINDSOR ............................................................................................................................ 5 BUCKLAND NEWTON ...................................................................................................................... 5 BURTON BRADSTOCK ..................................................................................................................... 5 CERNE ABBAS ................................................................................................................................. -

Beacon Ward Beaminster Ward

As at 21 June 2019 For 2 May 2019 Elections Electorate Postal No. No. Percentage Polling District Parish Parliamentary Voters assigned voted at Turnout Comments and suggestions Polling Station Code and Name (Parish Ward) Constituency to station station Initial Consultation ARO Comments received ARO comments and proposals BEACON WARD Ashmore Village Hall, Ashmore BEC1 - Ashmore Ashmore North Dorset 159 23 134 43 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Melbury Abbas and Cann Village BEC2 - Cann Cann North Dorset 433 102 539 150 27.8% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Hall, Melbury Abbas BEC13 - Melbury Melbury Abbas North Dorset 253 46 Abbas Fontmell Magna Village Hall, BEC3 - Compton Compton Abbas North Dorset 182 30 812 318 39.2% Current arrangements adequate – no Fontmell Magna Abbas changes proposed BEC4 - East East Orchard North Dorset 118 32 Orchard BEC6 - Fontmell Fontmell Magna North Dorset 595 86 Magna BEC12 - Margaret Margaret Marsh North Dorset 31 8 Marsh BEC17 - West West Orchard North Dorset 59 6 Orchard East Stour Village Hall, Back Street, BEC5 - Fifehead Fifehead Magdalen North Dorset 86 14 76 21 27.6% This building is also used for Gillingham Current arrangements adequate – no East Stour Magdalen ward changes proposed Manston Village Hall, Manston BEC7 - Hammoon Hammoon North Dorset 37 3 165 53 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed BEC11 - Manston Manston North Dorset 165 34 Shroton Village Hall, Main Street, BEC8 - Iwerne Iwerne Courtney North Dorset 345 56 281 119 -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : Thursday 7 May 2015

West Dorset District Council Authority Area - Parish & Town Councils STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : Thursday 7 May 2015 1. The name, description (if any) and address of each candidate, together with the names of proposer and seconder are show below for each Electoral Area (Parish or Town Council) 2. Where there are more validly nominated candidates for seats there were will be a poll between the hours of 7am to 10pm on Thursday 7 May 2015. 3. Any candidate against whom an entry in the last column (invalid) is made, is no longer standing at this election 4. Where contested this poll is taken together with elections to the West Dorset District Council and the Parliamentary Constituencies of South and West Dorset Abbotsbury Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid DONNELLY 13 West Street, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Company Director Arnold Patricia T, Cartlidge Arthur Kevin Edward Patrick Dorset, DT3 4JT FORD 11 West Street, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wood David J, Hutchings Donald P Henry Samuel Dorset, DT3 4JT ROPER Swan Inn, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Dorset, Meaker David, Peach Jason Graham Donald William DT3 4JL STEVENS 5 Rodden Row, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wenham Gordon C.B., Edwardes Leon T.J. David Kenneth Dorset, DT3 4JL Allington Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid BEER 13 Fulbrooks Lane, Bridport, Dorset, Independent Trott Deanna D, Trott Kevin M Anne-Marie DT6 5DW BOWDITCH 13 Court Orchard Road, Bridport, Dorset, Smith Carol A, Smith Timothy P Paul George DT6 5EY GAY 83 Alexandra Rd, Bridport, Dorset, Huxter Wendy M, Huxter Michael J Yes Ian Barry DT6 5AH LATHEY 83 Orchard Crescent, Bridport, Dorset, Thomas Barry N, Thomas Antoinette Y Philip John DT6 5HA WRIGHTON 72 Cherry Tree, Allington, Bridport, Dorset, Smith Timothy P, Smith Carol A Marion Adele DT6 5HQ Alton Pancras Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid CLIFTON The Old Post Office, Alton Pancras, Cowley William T, Dangerfield Sarah C.C. -

West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015

West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015 WEST DORSET, WEYMOUTH AND PORTLAND LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 Adopted October 2015 Local Plan West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015 Contents CHAPTER 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2. Environment and Climate Change.................................................................................. 19 CHAPTER 3. Achieving a Sustainable Pattern of Development .......................................................... 57 CHAPTER 4. Economy ......................................................................................................................... 81 CHAPTER 5. Housing ......................................................................................................................... 103 CHAPTER 6. Community Needs and Infrastructure ......................................................................... 113 CHAPTER 7. Weymouth .................................................................................................................... 133 CHAPTER 8. Portland ........................................................................................................................ 153 CHAPTER 9. Littlemoor Urban Extension ......................................................................................... 159 CHAPTER 10. Chickerell ...................................................................................................................... 163 -

Malabar, Nether Compton Sherborne, Dorset, DT9 4QJ

Malabar Sherborne, Dorset Malabar, Nether Compton Sherborne, Dorset, DT9 4QJ A substantial and versatile 3 / 4 bedroom bungalow with double garage, detached office/studio and beautiful gardens. Description Malabar is a substantial detached bungalow set in a beautiful location and which enjoys wonderful gardens. The bungalow, built a good distance down its own private gravelled front drive is very versatile and allows for any purchaser to easily recreate a fourth bedroom from the dressing room. The property enjoys the most beautiful gardens and a small brook flows through the grounds and under a small, attractive bridge. The accommodation has been much improved by the current vendor in recent years to include a contemporary fitted kitchen and tastefully fitted bathroom and ensuite. complimented by a family bathroom and an en-suite shower room with the master bedroom having the Internally, after parking within the large double garage the benefit of a previous bedroom 4, now converted into a house opens to a useful study which gives way to a dressing room with an adjoining entrance way. It is hallway. This in itself has access to both the front considered that this room could easily be reinstated as a gravelled area and the side garden and also leads to the fourth bedroom, (subject to any required utility room. Adjacent to this is the recently fitted kitchen/ consents). Malabar is offered with oil central heating, breakfast room with direct views towards the beautiful double glazing and it is without doubt in a beautifully front garden. The kitchen has a generous range of base peaceful location. -

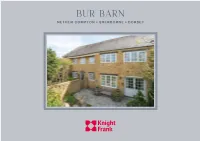

BUR BARN A4 4Pp.Indd

Bur Barn NETHER COMPTON SHERBORNE, DORSET Bur Barn NETHER COMPTON SHERBORNE, DORSET An attractive spacious Grade II listed barn conversion located centrally in this sought after village Dining room • Kitchen/breakfast room • Sitting room Utility room Cloakroom Master bedroom with dressing room and ensuite bathroom 2 Further bedrooms • Family bathroom Integral single garage Garden with private parking Sherborne 2¼ miles (London Waterloo 2¼ hours) Yeovil 2½ miles Wincanton/A303 11 miles Dorchester 19 miles (Distances & time approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Bur Barn The property is a Grade II listed barn timber wicket gate leads to the inner garden conversion forming part of a development which comprises an area of stone paved converted in 1990 The house is constructed terrace and a small lawn with stocked borders of stone elevations under a slate roof. There is on two sides. A stone path leads across the an integral single garage on the eastern end garden to a rear timber gate onto a nearby with twin double doors housing the oil tank. access path and this is flanked on one side The accommodation, which offers spacious by a small ornamental pond. The garden is and well proportioned reception rooms stocked with a variety of shrubs and small comprises: large dining room with staircase trees and is fully walled with some timber rising and understairs cupboard, kitchen/ trellis fencing on one boundary above a low breakfast room with range of fitted wall and wall. -

Sponsored Cycle Ride

DHCT – RIDE+STRIDE – LIST OF CHURCHES - Saturday 14th September 2019 - 10.00am to 6.00pm To help you locate churches and plan your route, the number beside each church indicates the (CofE) Deanery in which it is situated. Don’t forget that this list is also available on the website by Postcode, Location and Deanery. 1- Lyme Bay 2 - Dorchester 3 - Weymouth 4 - Sherborne 5 – Purbeck 6 - Milton & Blandford 7 - Wimborne 8 - Blackmore Vale 9 – Poole & N B’mouth 10- Christchurch 3 Abbotsbury 4 Castleton, Sherborne Old Church 5 Affpuddle 1 Catherston Leweston Holy Trinity 7 Alderholt 4 Cattistock 4 Folke 1 Allington 4 Caundle Marsh 6 Fontmell Magna 6 Almer 2 Cerne Abbas 2 Fordington 2 Athelhampton Orthodox 7 Chalbury 2 Frampton 2 Alton Pancras 5 Chaldon Herring (East Chaldon) 4 Frome St Quinton 5 Arne 6 Charlton Marshall 4 Frome Vauchurch 6 Ashmore 2 Charminster 8 Gillingham 1 Askerswell 1 Charmouth 8 Gillingham Roman Catholic 4 Batcombe 2 Cheselbourne 4 Glanvilles Wootton 1 Beaminster 4 Chetnole 2 Godmanstone 4 Beer Hackett 6 Chettle 6 Gussage All Saints 8 Belchalwell 3 Chickerell 6 Gussage St Michael 5 Bere Regis 1 Chideock 6 Gussage St Andrew 1 Bettiscombe 1 Chideock St Ignatius (RC) 4 Halstock 3 Bincombe 8 Child Okeford 8 Hammoon 4 Bishops Caundle 1 Chilcombe 7 Hampreston 1 Blackdown 4 Chilfrome 9 Hamworthy 6 Blandford Forum 10 Christchurch Priory 1 Hawkchurch Roman Catholic 5 Church Knowle 8 Hazelbury Bryan Methodist 7 Colehill 9 Heatherlands St Peter & St Paul 8 Compton Abbas 4 Hermitage United Reformed 2 Compton Valence 10 Highcliffe -

DORSET POLL BOOK for 1807 Taken from ------And

DORSET POLL BOOK FOR 1807 Taken from http://www.thedorsetpage.com/Genealogy/info/dorset1.txt ------------------------- and http://www.thedorsetpage.com/Genealogy/info/dorset2.txt Freeholder's Name Residence Situation of Freehold Occupier's Name Page ABBOTT John Wimborne Kingston 63 ABBOTT William Wimborne Badbury DOWNE J. & others 58 ABRAHAM R. Revd Ilminster Somerset Stockland North ENTICOTT John 30 ADAMS George Brokenhurst HAM Ibberton PHILIPS Benjamin 86 ADAMS Henry Up-Loders Up-Loders 28 ADAMS John Lyme Regis Lyme Regis & others 18 ADAMS Ralph Sherborn Abbots Fee & others 71 ADAMS Thomas Shaftesbury St Peter Shaft. 58 ADEY Thomas Poole Poole JEWELL Samuel 53 ADEY William Longfleet Poole PATTICK Samuel 53 ADNEY George Winterborne W Stoke Abbas STONE Daniel 21 ALDRIDGE John Poole Poole 53 ALLEN George West Chickerell West Chickerell 40 ALLEN George N. Poole Poole 53 ALLEN James West Chickerell West Chickerell 40 ALLEN John Portland Portland & tenant 49 ALLEN John Revd Crewkerne Maidon Newton 44 ALLEN Richard Compton Sussex Poole HAYWARD & BROWN 53 ALLEN Thomas Revd Shipton Beauchamp Thornford BOND------- 83 ALLEN William Dalwood Dalwood 48 ALLER Joshua Stowerpaine Stowerpaine 9 ALMER Robert Piddletown Tyneham 4 ALNER William Martock Bridport ROBERTS R. 15 AMES Benjamin Beaminster Mapperton 23 AMEY William Ilsington Tineleton 43 ANDERDON R.P. Esq Henley Somerset Stockland North THOMAS William 30 ANDRAS Thomas Lyme Regis Lyme Regis & others 18 ANDREWS Alexander Portland Portland 49 ANDREWS Daniel Portland Portland PEARCE W. 49 ANDREWS George Dorchester Hazelbury Bryan TOREVILLE George 6 ANDREWS J.S. Esq Chettle Orchard East GULLIVER Lemuel 69 ANDREWS James Shaftesbury St Jas Shaftesb 57 ANDREWS Jeremiah Shaftesbury St Peter Shaft. -

The Nether Compton Roman Coin Hoard in Its Archaeological Context

The Nether Compton Roman coin hoard in its archaeological context. John Oswin Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society 2011 i The Nether Compton Roman coin hoard in its archaeological context. John Oswin Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society © 2011 ii Abstract A hoard of some 22,500 Roman coins was unearthed in a field in Nether Compton parish in Dorset by a member of the Yeovil Metal Detector Club in 1989. It was not treasure trove under the rules then current. It remained in Dorset County Museum, Dorchester, without the resources to study it for a number of years before it was retrieved, broken up and sold, so it was never fully analysed. There was no indication of archaeological remains in the field where it was found, although there were unsubstantiated rumours of there being a Roman villa in the field to the west. A geophysical survey was instigated by a village resident and carried out by the Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society between 2009 and 2011, and this indicated significant Roman and possible pre-Roman activity in these two fields. An interim report was circulated in 2009, now superceded by this report. In memory of Denis Lansdell, a good and generous friend and mentor. iii Acknowledgements I would like to dedicate this survey to the memory of Denis Lansdell, a very good friend of mine, who lived in the village for a few years before his death in 1994. The work was instigated and supported by Elizabeth Adam of Nether Compton and her daughter Catherine. I acknowledge gratefully the opportunity to use the geophysical equipment, which belongs to the Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society. -

Dorset Community Transport Directory 2018 This Guide Provides Details of Voluntary Car Schemes, Dial-A-Rides and Other Community Transport Options Across Dorset

Dorset Community Transport Directory 2018 This guide provides details of voluntary car schemes, Dial-a-Rides and other community transport options across Dorset. Enabling communities in Dorset to thrive, now and for the future Dorset Community Transport Directory 2018 Contents Contents Page Main Index 1 About this Directory 2 Volunteering 3 Hospital Transport 3 Public Transport Information 4 Index of Transport schemes 5—7 Schemes 8 —85 1 Dorset Community Transport Directory 2018 About this Directory In the following pages you will find details of over 60 voluntary car schemes, dial-a-rides and other community transport initiatives across Dorset. The Directory is split by Council District, to help locate schemes nearest to you, and are listed in alphabetical order. Do check the listings for neighbouring communities as some schemes service villages across a wide area. Each page provides you with a little information about the scheme, details of which areas the scheme operates in and some contact details for you to make enquiries and to book the transport. The information listed was correct at the time of compilation but is subject to change. Please contact the scheme or service directly for more information. If you know of other schemes that operate in Dorset or if you wish to be included in this directory or have an amendment, please contact: Amanda Evans on 01305 224518 [email protected] Community Transport Information Line This is a service that enables people to find out if there is a community transport scheme in their area. Telephone 01305 221053 or go to: http://mapping.dorsetforyou.gov.uk/mylocal Important Note: We are not in a position to recommend a particular organisation, however this directory contains details of a number of independent sector providers of transport you may wish to contact. -

A Pretty Listed Grade Ii Thatched Gate Lodge On

A PRETTY LISTED GRADE II THATCHED GATE LODGE ON EDGE OF THIS POPULAR VILLAGE the round lodge, nether compton, dorset A PRETTY LISTED GRADE II THATCHED GATE LODGE ON EDGE OF THIS POPULAR VILLAGE the round lodge, nether compton, sherborne, dorset dt9 4qt Entrance hall w sitting room w dining room w kitchen w WC/utility w master bedroom with en suite shower room w three further bedrooms w Family bathroom w landscaped gardens Situation The Round Lodge is situated in a glorious rural location just a short distance from the pretty village of Nether Compton which includes many attractive local stone period cottages and houses as well as a parish church, public house and active village hall. The nearby Abbey town of Sherborne and regional centre of Yeovil provide an excellent variety of shopping, educational and recreational facilities. Communications in the area include mainline railway services at Sherborne or Yeovil Junction to London Waterloo or Yeovil Penn Mill to Weymouth or Bristol. The A303 can be joined to the north at Wincanton and this provides a route to London/Home Counties along the M3. Sporting facilities in the area include golf courses at Sherborne and Yeovil, sailing at Sutton Bingham Reservoir, horse racing at Exeter, Wincanton or Bath and other watersports can be enjoyed to the south along the Dorset coastline. The area is well served by independent schools at Sherborne Preparatory School, Sherborne School and Sherborne Girls, Leweston School, Hazelgrove, Perrott Hill and Port Regis. Description The Round Lodge is understood to have been built in circa 1826 and is justifiably listed Grade II as being of architectural interest.