The Kabir Documentaries of Shabnam Virmani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

10U/111121 (To Bejilled up by the Candidate by Blue/Black Ball-Point Pen)

Question Booklet No. 10U/111121 (To bejilled up by the candidate by blue/black ball-point pen) Roll No. LI_..L._.L..._L.-..JL--'_....l._....L_.J Roll No. (Write the digits in words) ............................................................................................... .. Serial No. of Answer Sheet .............................................. D~'y and Date ................................................................... ( Signature of Invigilator) INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES (Use only bluelblack ball-point pen in the space above and on both sides of the Answer Sheet) 1. Within 10 minutes of the issue of the Question Booklet, check the Question Booklet to ensure that it contains all the pages in correct sequence and that no page/question is missing. In case of faulty Question Booklet bring it to the notice oflhe Superintendentllnvigilators immediately to obtain a fresh Question Booklet. 2. Do not bring any loose paper, written or blank, inside the Examination Hall except the Admit Card without its envelope, .\. A separate Answer Sheet b,' given. It !J'hould not he folded or mutilated A second Answer Sheet shall not be provided. Only the Answer Sheet will be evaluated 4. Write your Roll Number and Serial Number oflhe Answer Sheet by pen in the space prvided above. 5. On the front page ofthe Answer Sheet, write hy pen your Roll Numher in the space provided at the top and hy darkening the circles at the bottom. AI!J'o, wherever applicahle, write the Question Booklet Numher and the Set Numher in appropriate places. 6. No overwriting is allowed in the entries of Roll No., Question Booklet no. and Set no. (if any) on OMR sheet and Roll No. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Unni Menon…. Is Basically a Malayalam Film Playback Singer

“FIRST ICSI-SIRC CSBF MUSICAL NITE” 11.11.2012 Sunday 6.05 p.m Kamarajar Arangam A/C Chennai In Association With Celebrity Singers . UNNI MENON . SRINIVAS . ANOORADA SRIRAM . MALATHY LAKSHMAN . MICHAEL AUGUSTINE Orchestra by THE VISION AND MISSION OF ICSI Vision : "To be a global leader in promoting Good Corporate Governance” Mission : "To develop high calibre professionals facilitating good Corporate Governance" The Institute The Institute of Company Secretaries of India(ICSI) is constituted under an Act of Parliament i.e. the Company Secretaries Act, 1980 (Act No. 56 of 1980). ICSI is the only recognized professional body in India to develop and regulate the profession of Company Secretaries in India. The Institute of Company Secretaries of India(ICSI) has on its rolls 25,132 members including 4,434 members holding certificate of the practice. The number of current students is over 2,30,000. The Institute of company Secretaries of India (ICSI) has its headquarters at New Delhi and four regional offices at New Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata and Mumbai and 68 Chapters in India. The ICSI has emerged as a premier professional body developing professionals specializing in Corporate Governance. Members of the Institute are rendering valuable services to the Government, Regulatory `bodies, Trade, Commerce, Industry and society at large. Objective of the Fund Financial Assistance in the event of Death of a member of CBSF Upto the age of 60 years • Upto Rs.3,00,000 in deserving cases on receipt of request subject to the Guidelines approved by the Managing -

Public Notice

16.09.2019 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS -----------------> 01 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS ----------------------------> 01 TO 139 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) --------------> 01 TO 12 ADVANCE LIST -------------------------------> 01 TO 122 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)---------> 123 TO 141 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST-MID)-----> 142 TO 154 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)-------------> 155 TO 163 COMPANY ------------------------------------> 164 TO 164 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY -----------------------> 165 TO 172 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY -----------------------> 173 TO 173 MEDIATION CAUSE LIST -----------------------> 01 TO 03 NOTES 1. Mentioning of urgent matters will be before Hon'ble DB-I at 10:30 a.m.. PUBLIC NOTICE It is hereby circulated for information of the public at large that in the process of taking further the concept of providing easy “access to justice”, a Toll Free Helpline No. 1888, is operational in English as well as Hindi vernacular, in Delhi High Court. Through this helpline, litigant or general public can have access to know about the facilities and services being rendered by the Registry of this Court such as availability of wheel chairs for differently abled persons, process to get entry gate pass, help for legal aid, procedure to approach Delhi International Arbitration Centre: Samadhan- Delhi High Court Mediation and Conciliation Centre, E-filing process, filing counter and listing of cases. To get immediate assistance, all concerned are requested to use Helpline No.1888. DELETIONS 1. LPA 589/2019 listed before Hon'ble DB-IV at item No.25 is deleted as the same is listed before Hon'ble DB-I. -

Celebrate 'Kabir in Every Sense' at the Third Edition of Mahindra Kabira

MEDIA RELEASE Celebrate ‘Kabir in Every Sense’ at the third edition of Mahindra Kabira Festival 16th – 18th November 2018 New Delhi. 24 July, 2018. The third edition of Mahindra Kabira Festival, to be held between 16 - 18th November, in Varanasi, will once again celebrate the spirit of 15th-century mystic poet Kabir in a rich two-day programme of music, literature, talks and city explorations. Conceived by the Mahindra group and leading performing arts entertainment company, Teamwork Arts, Mahindra Kabira Festival salutes the glorious simplicity of Kabir’s philosophy and poetry annually on the ghats of timeless Varanasi as the vast Ganga stands sentinel. Mahindra Kabira Festival will bring to music-lovers an invigorating Morning and Evening Music Programme that will take place at Guleria Ghat and Shivala Ghat respectively – with leading exponents of the Benares gharana and folk traditions, dadra, thumri, khayal gayaki styles, Sufiyana and ghazals, and pakhawaj and tabla players. The Festival promises an experience that truly is ‘Kabir in every sense’ and, apart from the music, features sessions on art and literature inspired by Kabir in the afternoons, delectable local cuisine and curated walks with famous local residents as guides for attendees as they discover the fascinating city of Varanasi. Having hosted renowned artistes like Kailash Kher, Shubha Mudgal and Kabir Café in the last two editions, this year will feature a Morning Music performance by Hindustani classical singer Vidya Rao, Literature Afternoon Sessions by writer and mythologist Devdutt Pattnaik and renowned Bhakti scholar Purushottam Agrawal and Evening Music performances by award-winning singer and composer Sonam Kalra of the Sufi Gospel Project fame, vani and bhajan singer Omprakash Nayak and many others from an eclectic line-up of artistes which will be announced soon. -

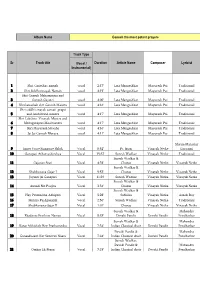

Album Name Ganesh the Most Potent Prayers Sr Track Title Track Type

Album Name Ganesh the most potent prayers Track Type Sr Track title (Vocal / Duration Artiste Name Composer Lyricist Instrumental) 1 Shri Ganeshay namah vocal 2:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 2 Shri Siddhivinayak Naman vocal 4:15' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri Ganesh Mahamantra and 3 Ganesh Gayatri vocal 4:00' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 4 Kleshanashak shri Ganesh Mantra vocal 4:16' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri siddhivinayak santati-prapti 5 and Aashirvaad mantra vocal 4:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri Lakshmi-Vinayak Mantra and 6 Mahaganapati Moolmantra vocal 4:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 7 Shri Mayuresh Stavaha vocal 4:16' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 8 Jai Jai Ganesh Moraya vocal 4:11' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shyam Manohar 9 Inner Voice Signature Shlok Vocal 0:52' Pt. Jasraj Vinayak Netke Goswami 10 Ganapati Atharvashirshya Vocal 15:37' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Traditional Suresh Wadkar & 11 Gajanan Stuti Vocal 4:35' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 12 Shubhanana Gajar I Vocal 5:53' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke 13 Jayanti jai Ganapati Vocal 11:39' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 14 Anaadi Nit Poojita Vocal 3:34' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 15 Hey Prarambha Adhipati Vocal 5:28' Sabhiha Vinayak Netke Ashok Roy 16 Mantra Pushpaanjali Vocal 2:56' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Traditional 17 Shubhanana Gajar II Vocal 1:01' Chorus Vinayak Netke -

CURRICULUM – VITAE [email protected]

CURRICULUM – VITAE [email protected] DR. PAMIL MODI A VERSATILE SINGER AND PERFORMER Assistant Professor Dept. of Music M.L.S. University, Udaipur Educational Qualifications Degrees Year Board/University SET 2015 RPSC, Ajmer Ph.D. 2009 Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur M.A. Music (Vocal) 2004 Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur Sangeet Alankar 2003 Surnanandan Bharti-Kolkotta M.A. Music (Alankar) 2001 Akhil Bhartiya Gandharv Mahavidhyalya Mandal-Mumbai B.A. 2002 Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur (Music,Eng.Lit, Geog.) Teaching Experience Presently working in the Department of Music as Assistant Professor, MLSU, Udaipur. Teaching experience in the Department of Music as a Lecturer in Aishwarya College for 2 years, (2008 to 2010). Had been associated with Mohan Lal Sukhadia University as a Guest Faculty in Dept. of Music for past 12 years, (2006 – 2018). Training and Teaching to students in Hindustani Vocal Classical Music of various age groups under the Organisation, Maharana Kumbha Sangeet Parishad. Worked as a Resource Person for Vocal Music Training in PIE, Rajasthan Patrika, Udaipur, 2004. Awards / Appreciations Bhaskar Woman of The Year Award-2019 by Deputy Chief Minister Sachin Pilot Jaipur. Woman of Substance by Big FM 92.7 and Aravli Foundation in 2019, Udaipur. Excellency Certificate by Ghazal Academy, Udaipur and Maharana Kumbha Sangeet Parishad, Udaipur, towards Music, July 2018. Received Gold Medal from Governor for Standing First in order of Merit in Music, in 2005. Awarded on International Women's Day in “Chingari Utsav” for contribution in Indian Classical Music by Rotary Club, Udaipur, 2016. Awarded by His Highness Maharana Arvind Singh Ji Mewar of Udaipur for excellent performance of Indian Classical Vocal Music on Guru Purnima, 2004. -

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Peter James Kvetko certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor ______________________________ Gerard Béhague ______________________________ Veit Erlmann ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Herman Van Olphen Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay by Peter James Kvetko, B.A.; M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 To Harold Ashenfelter and Amul Desai Preface A crowded, red double-decker bus pulls into the depot and comes to a rest amidst swirling dust and smoke. Its passengers slowly alight and begin to disperse into the muggy evening air. I step down from the bus and look left and right, trying to get my bearings. This is only my second day in Bombay and my first to venture out of the old city center and into the Northern suburbs. I approach a small circle of bus drivers and ticket takers, all clad in loose-fitting brown shirts and pants. They point me in the direction of my destination, the JVPD grounds, and I join the ranks of people marching west along a dusty, narrowing road. Before long, we are met by a colorful procession of drummers and dancers honoring the goddess Durga through thundering music and vigorous dance. The procession is met with little more than a few indifferent glances by tired workers walking home after a long day and grueling commute. -

An Exclusive Fusion Concert Featuring Celebrated Dancers and Musicians from India and France at the Royal Opera House, Mumbai

An Exclusive Fusion Concert featuring celebrated Dancers and Musicians from India and France at the Royal Opera House, Mumbai For Immediate Release Alliance Française de Bombay, The French Institute in India, Royal Opera House, Mumbai and Avid Learning present Khushboo: An Evening of Indo-French Music and Dance. A medley of talented musicians and dancers from France and India come together for a unique performance that highlights the best of both cultures and uncovers synergies between them while celebrating unique aspects of each! Please read below for a description of the performance: Eight masterful performers with eclectic talents and skills including Composer and Musician Titi Robin on Guitar and Buzuk, Murad Ali Khan on Sarangi, Rajasthani Folk Dancer Gulabo Sapera, Kathak Dancer Mahua Shankar, Vocalists Shuheb Hasan and Zohaib Hasan, Amaan Ali Khan on Tabla and Dino Banjara on Percussions will come together to create multidisciplinary dance and musical magic! Sarangi Maestro Murad Ali Khan and French composer Titi Robin have been working together on joint artistic projects for the last ten years, from the first recording of Laal Asmaan in Bombay (Blue Frog Label) to the international show Les Rives and their more recent album Rebel Diwana produced in Belgium. Padma Shri Gulabo Sapera and Titi Robin began their collaboration in the early ‘90s with the Gitans album, the first of a long series of recording, videos and numerous tours around the globe. These maestros reunite on our stage along with traditional Indian dance disciplinarian, Kathak star, Mahua Shankar. This concert will bring to life the tribal-gypsy dance style from Rajasthan and classic instruments and sounds from Europe - a wonderful blend of cultures. -

Track Name Singers VOCALS 1 RAMKALI Pt. Bhimsen Joshi 2 ASAWARI TODI Pt

Track name Singers VOCALS 1 RAMKALI Pt. Bhimsen Joshi 2 ASAWARI TODI Pt. Bhimsen Joshi 3 HINDOLIKA Pt. Bhimsen Joshi 4 Thumri-Bhairavi Pt. Bhimsen Joshi 5 SHANKARA MANIK VERMA 6 NAT MALHAR MANIK VERMA 7 POORIYA MANIK VERMA 8 PILOO MANIK VERMA 9 BIHAGADA PANDIT JASRAJ 10 MULTANI PANDIT JASRAJ 11 NAYAKI KANADA PANDIT JASRAJ 12 DIN KI PURIYA PANDIT JASRAJ 13 BHOOPALI MALINI RAJURKAR 14 SHANKARA MALINI RAJURKAR 15 SOHONI MALINI RAJURKAR 16 CHHAYANAT MALINI RAJURKAR 17 HAMEER MALINI RAJURKAR 18 ADANA MALINI RAJURKAR 19 YAMAN MALINI RAJURKAR 20 DURGA MALINI RAJURKAR 21 KHAMAJ MALINI RAJURKAR 22 TILAK-KAMOD MALINI RAJURKAR 23 BHAIRAVI MALINI RAJURKAR 24 ANAND BHAIRAV PANDIT JITENDRA ABHISHEKI 25 RAAG MALA PANDIT JITENDRA ABHISHEKI 26 KABIR BHAJAN PANDIT JITENDRA ABHISHEKI 27 SHIVMAT BHAIRAV PANDIT JITENDRA ABHISHEKI 28 LALIT BEGUM PARVEEN SULTANA 29 JOG BEGUM PARVEEN SULTANA 30 GUJRI JODI BEGUM PARVEEN SULTANA 31 KOMAL BHAIRAV BEGUM PARVEEN SULTANA 32 MARUBIHAG PANDIT VASANTRAO DESHPANDE 33 THUMRI MISHRA KHAMAJ PANDIT VASANTRAO DESHPANDE 34 JEEVANPURI PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 35 BAHAR PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 36 DHANBASANTI PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 37 DESHKAR PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 38 GUNAKALI PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 39 BILASKHANI-TODI PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 40 KAMOD PANDIT KUMAR GANDHARVA 41 MIYA KI TODI USTAD RASHID KHAN 42 BHATIYAR USTAD RASHID KHAN 43 MIYA KI TODI USTAD RASHID KHAN 44 BHATIYAR USTAD RASHID KHAN 45 BIHAG ASHWINI BHIDE-DESHPANDE 46 BHINNA SHADAJ ASHWINI BHIDE-DESHPANDE 47 JHINJHOTI ASHWINI BHIDE-DESHPANDE 48 NAYAKI KANADA ASHWINI -

Second Edition of Mahindra Kabira Festival to Take Place from 10 Th

MEDIA RELEASE Second edition of Mahindra Kabira Festival to take place from 10th – 12th November, 2017 Embrace ‘Kabir in every sense’ through the ghats and bylanes of Varanasi MEDIA KIT - Includes Photographs and Festival Announcements Taking off from a memorable inaugural edition last year, the Mahindra Kabira Festival returns to Varanasi for three days from the 10th – 12th of November 2017 with another sublime celebration of the mystical poet saint Kabir. The festival promises a specially curated experience of the life and works of Kabir, his music and poetry, and the city of Varanasi, his birthplace, unparalleled for its unique ambience, flavour, soul and history. Conceived by the Mahindra Group and leading performing arts entertainment company, Teamwork Arts, the festival will feature grassroots artistes as well as renowned names such as Bindumalini & Vedanth, Mahesha Ram, Nathoo Lal Solanki, Rashmi Agarwal, Harpreet Singh, and headline performances by the unmatched Kailash Kher and Shubha Mudgal. Kabir’s poetry is all about inclusiveness – and like last year, Mahindra Kabira Festival will celebrate this philosophy and bring to music-lovers an unforgettable experience. Leading exponents of the Benares gharana and folk traditions, Sufi music, dadra, thumri, khayal gayaki styles, ghazals and pakhawaj and the tabla are all set to enthrall audiences on the historic ghats of India’s holiest city, Varanasi which resonates with a mélange of voices and colours symbolic of India’s rich cultural matrix. “At Mahindra, we are committed to the preservation and promotion of the arts. We are delighted to present the Mahindra Kabira Festival in its second edition where leading artistes will perform works inspired by the legendary poet-saint with the famed Varanasi ghats forming a stunning backdrop.