Articles Rule of Law in Central and Eastern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Call to Censure the President

S. HRG. 109–524 AN EXAMINATION OF THE CALL TO CENSURE THE PRESIDENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 31, 2006 Serial No. J–109–66 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 28–341 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:36 Aug 16, 2006 Jkt 028341 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\28341.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cornyn, Hon. John, a U.S. Senator from the State of Texas .............................. -

Dear Virginians, Five Generations Ago, My Ancestors Were Freed from the Shackles of Slavery

REFORMING OUR CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM Dear Virginians, Five generations ago, my ancestors were freed from the shackles of slavery. Just two generations ago, my grandfather, one of Virginia’s first Black lawyers, was forced by Jim Crow to obtain his law degree in the north. And my father was one of the first to integrate his elementary school in 1960. As I travel throughout the Commonwealth and stand as an elected official in the former capital of the Confederacy, I often wonder how my ancestors would feel, and what they would think, about their descendant who has the opportunity to be Virginia’s first Black Attorney General. I’m running for Attorney General because we’ve made progress in building a more fair and equitable Virginia, but we all know we have not come far enough. The vestiges of slavery and Jim Crow live on in our Commonwealth’s criminal code, in our judicial system, and in our policing. They criminalize Black and Brown communities and make every Virginian less safe. In order to embrace the new Virginia decade, we must build a justice system that works for everybody in our Commonwealth, not just a select few. We have arrived at a true moment of opportunity in our country and in our Commonwealth. We must elect leaders who will rise to that moment and seize the chance to create real change in our justice system, rather than continuing with those who have proven time and time again that they will only do the bare minimum to get by. For his entire career, Mark Herring has shown that he will follow when he has to, but he will not lead. -

Professor C. Raj Kumar Professor & Vice Chancellor O.P

Curriculum Vitae PROFESSOR C. RAJ KUMAR PROFESSOR & VICE CHANCELLOR O.P. JINDAL GLOBAL UNIVERSITY Tel: (+91-130) 4091900; Fax: (+91-130) 4091888 Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.jgu.edu.in I. CURENT AFFILIATION (since 2009) Vice Chancellor, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana (NCR of Delhi) Dean, Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat, Haryana (NCR of Delhi) Director, International Institute for Higher Education Research & Capacity Building, Sonipat, Haryana (NCR of Delhi) II. EDUCATION Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Doctor of Legal Science (S.J.D.), 2011 Harvard Law School, United States of America LL.M. (Master of Laws), 2000. University of Oxford, United Kingdom B.C.L. (Bachelor of Civil Law), 1999. Faculty of Law, University of Delhi, India LL.B. (Bachelor of Laws), 1997. Loyola College, University of Madras, India B.Com. (Bachelor of Commerce), 1994. III. AWARDS/SCHOLARSHIPS/FELLOWSHIPS (ANNEX I) Scholarships and fellowships awarded by the University of Oxford, Harvard Law School, Harvard University, Loyola College, University of Madras, Monash University and Indiana University. IV. RESEARCH GRANTS/FUNDS (ANNEX II) Received research grants and funds from various educational and research institutions, foundations, and inter-governmental organisations including City University of Hong Kong; Sumitomo Foundation, Tokyo, Japan; and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). V. PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Passed the New York Bar Exam (July 2001) and was admitted to the Bar of the State of New York, U.S.A., as an Attorney and Counsellor at Law in February 2002; admitted to the Bar Council of Delhi, New Delhi, India, in August 1997. -

Attendee Handout Packet 7.30.2020 AAM Webinar

Association of Attorney-Mediators Webinar - Confidentiality in the Age of Online Mediations: Points to Ponder July 30, 2020 On July 30, 2020, from 11:30 a.m. to 12:45 p.m., the Association of Attorney Mediators will be presenting a webinar during which a moderator and four panelists will discuss the issues of confidentiality and discoverability that come with conducting mediations on platforms such as Zoom, with participants often in different states with different laws that govern mediation confidentiality. The panelists and moderator are from across the United States, as will be the attendees. The following panel members will discuss the enforceability of Confidentiality Agreements, the conflicts of laws principles that arise with multi-state mediations, the potential liability for confidentiality breaches of which mediators must be aware, and other salient issues. Panelists will be Danielle Hargrove, Jeff Kichaven, Jean Lawler and Michael Leech. Panel will be moderated by AAM President, Jimmy Lawson. Agenda 11:30-11:35: Welcome and Introduction of Panel Jimmy Lawson, Moderator 11:35-11:45: Brief synopsis of the substance of Kichaven’s articles Jeff Kichaven, Panelist 11:45-12:45 Discussion of mediation confidentiality. Various questions will be asked of the panel for discussion Table of Contents Speakers Bios Pages 2-3 Article: Mediator Confidentiality Promises Carry Serious Risks Pages 4-6 Article: What You Say In Online Mediation May Be Discoverable Pages 7-12 Article: Nix Your Mediators Prospective Waiver Of Liability Pages 13-16 1 Association of Attorney-Mediators Webinar - Confidentiality in the Age of Online Mediations: Points to Ponder Speakers and Panelists – July 30, 2020 Danielle L. -

Looking Back to Go Forward: Remaking Detainee Policy*

Looking Back to Go Forward: Remaking U.S. Detainee Policy* by James M. Durant, III, Lt Col USAF Deputy Head, Department of Law United States Air Force Academy Frank Anechiarico Distinguished Visiting Professor of Law United States Air Force Academy Maynard-Knox Professor of Government and Law Hamilton College [WEB VERSION] April, 2009 © James Durant, III, Frank Anechiarico * This article does not reflect the views of the Air Force, the United States Department of Defense, or the United States Government. “By mid-1966 the U.S. government had begun to fear for the welfare of American pilots and other prisoners held in Hanoi. Captured in the midst of an undeclared war, these men were labeled war criminals. .Anxious to make certain that they were covered by the Geneva Conventions and not tortured into making ‘confessions’ or brought to trial and executed, U.S. Ambassador-at-Large Averell Harriman asked [ New Yorker correspondent Robert] Shaplen to contact the North Vietnamese.” - Thomas Bass (2009) ++ Introduction This article, first explains why and how detainee policy as applied to those labeled enemy combatants, collapsed and failed by 2008. Second, we argue that the most direct and effective way for the Obama Administration to reassert the rule of law and protect national security in the treatment of detainees is to direct review and prosecution of detainee cases to U.S. Attorneys and adjudication of charges against them to the federal courts. The immediate relevance of this topic is raised by the decision of the Obama Administration to use the federal courts to try Ali Saleh Kahah al-Marri in a (civilian) criminal court. -

Home Study Programs Accredited As of Friday, August 13, 2021 General Ethics Course ID Seminar Name Provider Date Credits Credits

Home Study Programs Accredited as of Friday, September 3, 2021 General Ethics Course ID Seminar Name Provider Date Credits Credits 775960 TECH POLICIES FOR LAW FIRMS ABA 2019 2 780042 #ITSMYLANE:LGL MEDICAL ETHICS ABA 2019 2 0 788385 #METOO CLASS ACTION UPDATES ABA 2020 1 0 787888 100 YEARS ACCESS TO JUSTICE ABA 2020 1 0 775395 1031 EXCHANGES: NEW TAX ACT ABA 2018 2 770878 1041 FIDUCIARY INCOME TAX RTRN ABA 2019 2 790283 1782 CONUNDRUM ABA 2020 2 778467 19TH AMEND THEN & NOW: 21ST CE ABA 2019 2 0 791776 1-A SHARPER FOCUS: 43RD ANNL ABA 2020 4 788727 20 FED PROCURMNT ETHICS SOCIAL ABA 2020 3 2.4 788725 20 FED PROCURMNT:ADR ABA 2020 2 0 788728 20 FED PROCURMNT:GOV CONSTUCT ABA 2020 2 0 788726 20 FED PROCURMNT:WHITHER WHETH ABA 2020 2 0 775850 2017 SANCTIONS YEAR IN REVIEW ABA 2019 2 776071 2017 TAX ACT, ADVICE & ETHICS ABA 2019 2 1.8 775572 2017 TAX ACT: CORP TRANSACTNS ABA 2018 2 775609 2017 TAX ACT: FIRM PLANNING ABA 2018 2 775554 2017 TAX ACT: LAW FIRM PLAN ABA 2018 2 775532 2017 TAX ACT: NEED TO KNOW ABA 2018 2 775859 2017 TAX REFORM: YOUR FIRM ABA 2019 2 776201 2017 TAX REFORM: YOUR FIRM ABA 2017 1 775860 2017 US EXPORT CONTROLS ABA 2019 2 775607 2018 SUPREME COURT TERM ABA 2018 2 775380 2018 TAX ACT: REAL ESTATE LWYR ABA 2018 2 784443 2019 CORONAVIRUS: PUB HEALTH ABA 2020 2 0 780047 2019 ESTATE PLANNING HOT TOPIC ABA 2019 2 0 784491 2019 PRIVATE TARGET DEAL POINT ABA 2020 2 0 784557 2020 E-DISCOVERY:ETHICS ABA 2020 2 1.2 784558 2020 E-DISCOVERY:FORENS DATA ABA 2020 4 0 785980 2020 ILS VAM BEWARE FINE PRINT ABA 2020 2 0 785983 2020 -

Experts Say Conway May Have Broken Ethics Rule by Touting Ivanka Trump'

From: Tyler Countie To: Contact OGE Subject: Violation of Government Ethics Question Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 11:26:19 AM Hello, I was wondering if the following tweet would constitute a violation of US Government ethics: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/829356871848951809 How can the President of the United States put pressure on a company for no longer selling his daughter's things? In text it says: Donald J. Trump @realDonaldTrump My daughter Ivanka has been treated so unfairly by @Nordstrom. She is a great person -- always pushing me to do the right thing! Terrible! 10:51am · 8 Feb 2017 · Twitter for iPhone Have a good day, Tyler From: Russell R. To: Contact OGE Subject: Trump"s message to Nordstrom Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:03:26 PM What exactly does your office do if it's not investigating ethics issues? Did you even see Trump's Tweet about Nordstrom (in regards to his DAUGHTER'S clothing line)? Not to be rude, but the president seems to have more conflicts of interest than someone who has a lot of conflicts of interests. Yeah, our GREAT leader worrying about his daughters CLOTHING LINE being dropped, while people are dying from other issues not being addressed all over the country. Maybe she should go into politics so she can complain for herself since government officials can do that. How about at least doing your jobs, instead of not?!?!? Ridiculous!!!!!!!!!!!! I guess it's just easier to do nothing, huh? Sincerely, Russell R. From: Mike Ahlquist To: Contact OGE Cc: Mike Ahlquist Subject: White House Ethics Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:23:01 PM Is it Ethical and or Legal for the Executive Branch to be conducting Family Business through Government channels. -

Congressional Record—House H11279

October 13, 2009 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H11279 So there are still a lot of good things that responsibility here to enable all that sit in these court cases, we spend being worked on. This bill gets better families in this country to have access our time making sure people’s rights and better by the day, and I believe we, and to be able to afford quality health are protected. And we have a whole se- again, are at a historic point here and care. ries of cases that establish rights of we are going to be able to just provide Thank you so much for bringing us criminal cases. Enough of you have stability and security to this country together, Representative PINGREE. watched television to know a lot in terms of our health care. And, to Ms. PINGREE of Maine. Well, thank about—we’re some of the most edu- me, we have to continue to sharpen our you to all my colleagues for being here cated, nonlawyers in the country, the pencils, as Representative TONKO says, tonight. You’re absolutely right. We’ve folks who watch television in the and continue to find ways to save with talked about a variety of issues, and I United States, because we know about this bill and also to provide even better want to just end on the same note that Miranda rights. So we know about care for citizens of all ages. you did. This is what is right about other rights. In other countries maybe Ms. PINGREE of Maine. -

Nigeria's Struggle with Corruption Hearing

NIGERIA’S STRUGGLE WITH CORRUPTION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 18, 2006 Serial No. 109–172 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–648PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 12:05 Jul 17, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\AGI\051806\27648.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, HOWARD L. BERMAN, California Vice Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American ELTON GALLEGLY, California Samoa ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California PETER T. KING, New York ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York DARRELL ISSA, California BARBARA LEE, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon MARK GREEN, Wisconsin SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada JERRY WELLER, Illinois GRACE F. -

The International Sports Law Journal 2005, No

2005/3-4 The Pyramid and EC law Status of Players’ Agents Simutenkov Case IAAF Arbitration Panel CAS Ad Hoc Division in Athens An Irish CAS? Professional Sport in Poland Sports Image Rights Homegrown Players TV rights in Bulgarian Football Code of Ethics in Romania CMS Derks Star Busmann It’s pretty clear. As the keeper you have only one goal: to stop the balls whizzing past your ears. A flawless performance, that’s what it’s all about. On the ball, right through the match. With your eye on the defence. You have to focus on that one goal. And pounce on that one ball. Because keeping the score at nil is all that matters. ...on the ball. Being on the ball is just as important in business as in hockey. CMS Derks Star Busmann supports your business with full legal and fiscal services. A goal-focused and practical approach with you at the centre. Cases and faces is what CMS Derks Star Busmann is all about. Contact our sports law specialists Eric Vilé ([email protected]), Dolph Segaar ([email protected]) or Robert Jan Dil ([email protected]). www.cmsderks.nl CONTENTS Editorial 2 ARTICLES Is the Pyramid Compatible with EC Law? 3 The IAAF Arbitration Panel. The Heritage of Two Stephen Weatherill Decades of Arbitration in Doping-Related Disputes Christoph Vedder 16 The Laurent Piau Case of the ECJ on the Status of Players( Agents 8 The Ad Hoc Division of the Court of Arbitration Roberto Branco Martins for Sport at the Athens 2004 Olympic Games - An Overview 23 The Simutenkov case: Russian Players are Domenico Di Pietro Equal to European Union Players 13 Frank Hendrickx An ‘Irish Court of Arbitration for Sport’? 28 Michelle de Bruin PAPERS Professional Sport in Poland. -

Spring/Summer 2004

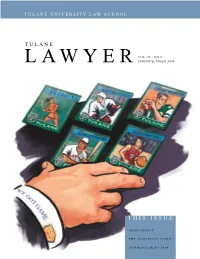

TULANE UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL TULANE VOL. 22 - NO.2 LAWYERSPRING/SUMMER 2004 THIS ISSUE GOOD SPORTS THE APOLITICAL CLINIC COMMENCEMENT 2004 CONTENTS 20 GOOD SPORTS Despite its big-money contracts, celebrity LAWRENCE PONOROFF athletes, and mega-endorsement deals, the business of sports law is more than simply DEAN “show me the money.” See how several alums handle the nuts and bolts of the job. ANN SALZER ASSISTANT DEAN ELLEN J. BRIERRE DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI AFFAIRS 26 COMMENCEMENT ’04 WINNIE BEUERMAN Graduation day in pictures DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT PAMBY LEVERT BARFIELD ASST. DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT NICK MARINELLO 2 FROM THE DEAN EDITOR 4 BRIEFS H DESIGN CONSULTATION 10 FACULTY NOTEBOOK CONTRIBUTORS 15 PUBLICATIONS & PRESENTATIONS ADAM BABICH 28 CLASS NOTES HUGH DASCHBACH ROBERT FORCE 38 REUNIONS PAM MICHIELS (L ’90) MARY MOUTON (L ’90) 40 TAX TOPICS LIZBETH TURNER (L ’85) On the cover —Tulane lawyers stack the SPRING/SUMMER 2004 deck of the sport law biz. Illustration by Michael Krider. TULANE LAWYER is published by the Tulane Law School and is sent to the school’s alumni, faculty, staff and friends. TULANE LAWYER SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO: Alumni Development and Information Services, “ ... to be a good sports lawyer, you have to be a good broad-based lawyer. 3439 Prytania St., Ste. 400, New Orleans, LA 70115. You have sports clients, but you are dealing with business enterprises, income tax, antitrust issues, labor law, and intellectual property.” 1 Tulane University is an Affirmative Action/Equal Employment Opportunity institution. FROM THE DEAN GROWTH AND RENEWAL Dean Lawrence Ponoroff with Rose LeBreton (L ’76), chair of the New Orleans alumni chapter, and BY DEAN LAWRENCE PONOROFF Maj. -

OGE Receives Inquiries from the Public in Several Different Forms. by Phone, Email, Postal Mail and Faxes

1. How are these contacts processed by OGE? OGE receives inquiries from the public in several different forms. By phone, email, postal mail and faxes. OGE has a team of employees responsible for processing these inquiries. For ContactOGE inquiries that do not prompt a response: Phone – Log the call in the phone log. Email – File the email to one of the “topic” folders or the “spam”. Spam is defined as advertisements, emails sent to multiple email addresses and not directed to email. Postmarked Mail/Fax – File the Postmarked Mail/Fax in the appropriate monthly folder by topic. For ContactOGE inquiries that prompt a response: Phone – create an AIMs entry. Email – create an AIMS entry and file the email to the response sent folder. Postmarked Mail/Fax – create an AIMS entry and file the Postmarked Mail/Fax in the appropriate monthly folder. For ContactOGE inquires that require a referral (including inquiries from the media, IGs, congress, speaking requests): Phone: forward the call to the appropriate individual Email: forward the email to the appropriate individual and file in the referred email folder Postmarked Mail/Fax: give the piece of correspondence to the appropriate individual • Are the contacts all individually looked at? No, given the volume OGE is not able to individually look at or respond to every contact. (For example, we received a high volume of petitions, those were automatically sent to a folder in Outlook). Mitigating steps: Created an auto response to our email that directs Examples of inquries that OGE responds to or takes action: . Refer media calls to press officer .