Mitigating Human Conflicts with Livestock Guardian Dogs in Extensive Sheep Grazing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis 7 Einfuhrung 67 Sibirischer Husky (Siberian Husky) 68 Alaskan Malamute 9 Lexikon der Fachbegriffe 69 Samojede (Samojedskaja) 71 Weitere Hirtenhunde 11 Rettungshunde 73 Jagdhunde: Vorstehhunde 12 Leonberger 13 Bernhardiner (St. Bernhardshund) 74 Pointer 14 Neufundländer und Landseer 76 Gordon-Setter 16 Pyrenäenberghund (Chien des Pyrenees) 76 Irischer Setter (Irish Setter) 78 Englischer Setter (English Setter) 79 Französischer Vorstehhund (Braque Francais)' 17 Wachhunde und Schutzhunde 80 Braque d'Auvergne 81 Braque Ari6geois (Braque de PAriege) 18 Boxer 82 Epagneul Breton 20 Dobermann 82 Epagneul Francais 22 Schnauzer 83 Epagneul Picard 25 Deutsche Dogge 84 Epagneul de Pont-Audemere 28 Hovawart 85 Korthals (Griffen ä Poil Dur) 29 Rottweiler 85 Boulet (Griffen ä Poil Laineux) 30 Bordeaux-Dogge (Dogue de Bordeaux) 86 Spinone Italiano 31 Bulldogge (Bulldog) 87 Italienischer Vorstehhund (Bracco Italiano) 32 Mastiff 88 Kurzhaariger Deutscher Vorstehhund (Kurzhaar) 33 Bullmastiff 89 Drahthaariger Deutscher Vorstehhund (Drahthaar) 34 Airedale-Terrier 90 Langhaariger Deutscher Vorstehhund (Langhaar) 35 Italienische Dogge (Mastino Napoletano) 91 Weimaraner 36 Chow-Chow 92 Großer und Kleiner Münsterländer 37 Dalmatiner 92 Perdiguero de Burgos 38 Weitere Wach- und Schutzhunde 94 Balearenlaufhund (Ibizahund, Podenco Ibicenco) 95 Portugiesischer Vorstehhund (Perdigueiro Portugufis) 96 Kurzhaariger Ungarischer Vorstehhund (Vizsla) 97 Tschechischer Vorstehhund (Cesk£ Funsek) 39 Gebrauchs- und Arbeitshunde: Hütehunde, Schäferhunde, -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

Genomic Characterization of the Three Balkan Livestock Guardian Dogs

sustainability Article Genomic Characterization of the Three Balkan Livestock Guardian Dogs Mateja Janeš 1,2 , Minja Zorc 3 , Maja Ferenˇcakovi´c 1, Ino Curik 1, Peter Dovˇc 3 and Vlatka Cubric-Curik 1,* 1 Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (I.C.) 2 The Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH25 9RG, UK 3 Biotechnical Faculty Department of Animal Science, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (P.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-239-4008 Abstract: Balkan Livestock Guardian Dogs (LGD) were bred to help protect sheep flocks in sparsely populated, remote mountainous areas in the Balkans. The aim of this study was genomic charac- terization (107,403 autosomal SNPs) of the three LGD breeds from the Balkans (Karst Shepherd, Sharplanina Dog, and Tornjak). Our analyses were performed on 44 dogs representing three Balkan LGD breeds, as well as on 79 publicly available genotypes representing eight other LGD breeds, 70 individuals representing seven popular breeds, and 18 gray wolves. The results of multivariate, phylogenetic, clustering (STRUCTURE), and FST differentiation analyses showed that the three Balkan LGD breeds are genetically distinct populations. While the Sharplanina Dog and Tornjak are closely related to other LGD breeds, the Karst Shepherd is a slightly genetically distinct population with estimated influence from German Shepard (Treemix analysis). Estimated genomic diversity was high with low inbreeding in Sharplanina Dog (Ho = 0.315, He = 0.315, and FROH>2Mb = 0.020) and Citation: Janeš, M.; Zorc, M.; Tornjak (Ho = 0.301, He = 0.301, and FROH>2Mb = 0.033) breeds. -

Quiz Sheets BDB JWB 0513.Indd

2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write one breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet and receive one point for each correct answer. There’s an extra five points on offer for those that can find correct answers for Q, U, X and Z! A N B O C P D Q E R F S G T H U I V J W K X L Y M Z Dogs for the Disabled The Frances Hay Centre, Blacklocks Hill, Banbury, Oxon, OX17 2BS Tel: 01295 252600 www.dogsforthedisabled.org supporting Registered Charity No. 1092960 (England & Wales) Registered in Scotland: SCO 39828 ANSWERS 2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write a breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet (one point each). Additional five points each if you get the correct answers for letters Q, U, X or Z. Or two points each for the best imaginative breed you come up with. A. Curly-coated Retriever I. P. Tibetan Spaniel Affenpinscher Cuvac Ibizan Hound Papillon Tibetan TerrieR Afghan Hound Irish Terrier Parson Russell Terrier Airedale Terrier D Irish Setter Pekingese U. Akita Inu Dachshund Irish Water Spaniel Pembroke Corgi No Breed Found Alaskan Husky Dalmatian Irish Wolfhound Peruvian Hairless Dog Alaskan Malamute Dandie Dinmont Terrier Italian Greyhound Pharaoh Hound V. Alsatian Danish Chicken Dog Italian Spinone Pointer Valley Bulldog American Bulldog Danish Mastiff Pomeranian Vanguard Bulldog American Cocker Deutsche Dogge J. Portugese Water Dog Victorian Bulldog Spaniel Dingo Jack Russel Terrier Poodle Villano de Las American Eskimo Dog Doberman Japanese Akita Pug Encartaciones American Pit Bull Terrier Dogo Argentino Japanese Chin Puli Vizsla Anatolian Shepherd Dogue de Bordeaux Jindo Pumi Volpino Italiano Dog Vucciriscu Appenzeller Moutain E. -

Livestock Guardian Dogs Tompkins Conservation Wildlife Bulletin Number 2, March 2017

LIVESTOCK GUARDIAN DOGS TOMPKINS CONSERVATION WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2, MARCH 2017 Livestock vs. Predators TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation PAGE 01 through the use of livestock guardian dogs Livestock vs. Predators: Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation through the use Since humans began domesti- stock and wild predators. Histor- of livestock guardian dogs cating animals, it has been nec- ically, humans have attempted PAGE 04 essary to protect livestock from to resolve this conflict through Livestock Guardian Dogs, wild predators. To this day, pre- a series of predator population an Ancient Tool in dation of livestock is one of the control measures including the Modern Times most prominent global hu- use of traps, hunting, and indis- PAGE 06 man-wildlife conflicts. Interest- criminate and nonselective poi- What Is the Job of a ingly, one of our most ancient soning—methods which are of- Livestock Guardian Dog? domestic companions, the dog, ten cruel and inefficient. was once a predator. One of the greatest chal- PAGE 07 The competition between lenges lies in successfully im- Breeds of Livestock man and wildlife for natural plementing effective measures Guardian Dogs spaces and resources is often that mitigate the negative im- PAGE 08 considered the main source of pacts of this conflict. It is imper- The Presence of Livestock conflict between domestic live- ative to ensure the protection of Guardian Dogs in Chile WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2 MARCH 2017 man and his resources, includ- tion in predators is lower than PAGE 10 ing livestock, without compro- that of the United States, where Livestock in the Chacabuco Valley mising the conservation of the the losses are due to a variety of and the Transition Toward the Future Patagonia National Park native biodiversity. -

Breeds of Cats and Dogs

Breeds of Dogs and Cats Floron C. Faries, Jr. DVM, MS Objectives Discuss the evolution of man’s relationship with dogs and cats Describe the characteristics shared by members of the Canidae family Describe the classification system for dogs List the uses for different breeds of dogs Identify and describe the different breeds of dogs Describe the characteristics shared by members of the family Felidae Describe the classification system for cats Identify and describe the different cat breeds History of Dogs In family Canidae Direct descendents of the wolf Wolf’s scientific name – Canis lupus Dog’s scientific name – Canis familiaris Domestication a few 1,000 years Greece Herding dogs Guarding dogs Hunting dogs Egypt Dogs used in war Bred based on purpose Climate Environment Master’s preference – herding, guarding, hunting 72 million dogs live in U.S. One dog per household in half American family homes More than 228 pure breeds More than 100 mixed breeds Stimulate income of dog industries $11 billion annual sales of dog food Accessory manufacturers Veterinarians Pharmaceutical industry Breeders Racers Trainers Herders Hunters Serve humans Protection Sight Hearing Security Companionship Characteristics of Dogs Size Height 6 inches to 40 inches at the shoulder Life expectancy 9 to 15 years, some 20 years Small dogs live longer than large dogs Common traits Shed hair once a year Non-retractable claws 42 adult teeth Pointed canine teeth Sweating Sweat glands on nose and feet Panting Hearing -

The Breeds Brief

THE BREEDS IN BRIEF No. 75 Puli IJlj HEN most people think of P. T. Since coming to the United States V Barnum they remember only h.is the Puli has made amazing progress flair for exploitation, but the really -and that despite the fact that World important fact about the great show War II hampered import~tions. By man was his ability to recognize tal 1944 it had moved up to 73rd place ent. He brought acts from all over the among the 111 breeds recognized, world and then publicized them to the the yearly registration, however, being limit. Perhaps they received an inor only 21. But in 1946 there were 4':i dinate amount of dramatization, but specimens entered in the Stud Book basically they were good acts that and in 1947 there were 42. This means could not be excelled in their time. that there is now a good supply of Barnum is no longer with us, but it foundation stock from which - plus seems that he has left a blanket legacy some more importations-there should to the American people. This country soon be enough breeding stock to sat is still fast on the uptake-quick to isfy an ever-increasing demand for recognize talent and quality-and in puppies as either pets or working dogs. no fie ld is it more apparent than in It seems as if the working qualities pure-bred dogdom. of the Puli will never be overlooked One of the finest breeds to feel the impetus of American recognition is that old Hungarian sheep herding dog, the Puli-75th topic in this series on all the pure-breds of the United States -which was first admitted to the Stud Book in the fall of 1936. -

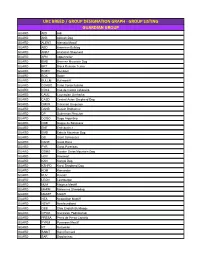

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

Tacoma Kennel Club, Inc. (American Kennel Club Licensed) Saturday & Sunday – April 24-25, 2021

Tacoma Kennel Club, Inc. (American Kennel Club Licensed) Saturday & Sunday – April 24-25, 2021 OFFICIAL NOTICE: SUBSTITUTION OF JUDGES – Reference Chapter 7, Section 8 of AKC Rules and Chapter 1, Section 26 of Obedience Regulations: Owner has the right to withdraw his entry and have his entry fee refunded provided notification of his withdrawal is received no later than one half-hour prior to the start of any regular judging. MRS. FAYE STRAUSS AND MRS. PAT PUTMAN WILL BE UNABLE TO FULFILL THEIR ASSIGNMENTS. THE FOLLOWING CHANGES HAVE BEEN MADE. SATURDAY NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - KATHLEEN J. BROCK: Sporting Group, Barbet, Lagotto Romagnolo, Nederlandse Kooikerhondie, Chesapeake Bay Retriever, Labrador Retriever, Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, English Setter, Irish Setter, Irish Red & White Setter, American Water Spaniel, Boykin Spaniel, Clumber Spaniel, Spinone Italiano, Vizsla, Weimaraner, Wirehaired Pointing, Griffon, Wirehaired Vizsla, Beagle (13”), Beagle(15”). NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - CHRISTIE MARTINEZ: Pug, American Eskimo Dogs, Chow Chow, Lhasa Apso. NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - JANE E TREIBER: Anatolian Shepherd Dog. NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - MARILYN VAN VLEIT: Herding Group, NOHS Working Group, Australian Cattle Dogs, Bearded Collies, Beauceron, Belgian Laeknois, Belgian Malinois, Belgian Sheepdogs, Bergamasco Sheepdog, Berger Picard, Border Collie, Briard, Canaan Dog, Cardigan Welsh Corgi, Entlebucher Mountain Dog, Finnish Lapphund, German Shepherd Dog, Icelandic Sheepdog, Miniature American Shepherd, Norwegian Buhund, Old English Sheepdog, Polish Lowland Sheepdog. NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - LEE WHITTIER: Havanese, Shih Tzu, Silky Terrier, Toy Fox Terrier. NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - R.C. WILLIAMS: Toy Poodles, Boston Terriers, Bulldog, Miniature Poodle, Standard Poodle. SUNDAY NEW SCHEDULED JUDGE - SANDRA BINGHAM-PORTER: Non-Sporting Group, Finnish Spitz. -

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/As Of: Sept

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/as of: Sept. 2016 A AP Affenpinscher / Monkey Terrier AH Afghanischer Windhund / Afgan Hound AID Atlas Berghund / Atlas Mountain Dog (Aidi) AT Airedale Terrier AK Akita AM Alaskan Malamute DBR Alpenländische Dachsbracke / Alpine Basset Hound AA American Akita ACS American Cocker Spaniel / American Cocker Spaniel AFH Amerikanischer Fuchshund / American Foxhound AST American Staffordshire Terrier AWS Amerikanischer Wasserspaniel / American Water Spaniel AFPV Small French English Hound (Anglo-francais de petite venerie) APPS Appenzeller Sennenhund / Appenzell Mountain Dog ARIE Ariegeois / Arigie Hound ACD Australischer Treibhund / Australian Cattledog KELP Australian Kelpie ASH Australian Shepherd SILT Australian Silky Terrier STCD Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog AUST Australischer Terrier / Australian Terrier AZ Azawakh B BARB Franzosicher Wasserhund / French Water Dog (Barbet) BAR Barsoi / Russian Wolfhound (Borzoi) BAJI Basenji BAN Basst Artesien Normad / Norman Artesien Basset (Basset artesien normand) BBG Blauer Basset der Gascogne / Bue Cascony Basset (Basset bleu de Gascogne) BFB Tawny Brittany Basset (Basset fauve de Bretagne) BASH Basset Hound BGS Bayrischer Gebirgsschweisshund / Bavarian Mountain Hound BG Beagle BH Beagle Harrier BC Bearded Collie BET Bedlington Terrier BBS Weisser Schweizer Schäferhund / White Swiss Shepherd Dog (Berger Blanc Suisse) BBC Beauceron (Berger de Beauce) BBR Briard (Berger de Brie) BPIC Picardieschäferhund / Picardy Shepdog (Berger de Picardie (Berger Picard)) -

HSVMA Guide to Congenital and Heritable Disorders in Dogs

GUIDE TO CONGENITAL AND HERITABLE DISORDERS IN DOGS Includes Genetic Predisposition to Diseases Special thanks to W. Jean Dodds, D.V.M. for researching and compiling the information contained in this guide. Dr. Dodds is a world-renowned vaccine research scientist with expertise in hematology, immunology, endocrinology and nutrition. Published by The Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association P.O. Box 208, Davis, CA 95617, Phone: 530-759-8106; Fax: 530-759-8116 First printing: August 1994, revised August 1997, November 2000, January 2004, March 2006, and May 2011. Introduction: Purebred dogs of many breeds and even mixed breed dogs are prone to specific abnormalities which may be familial or genetic in nature. Often, these health problems are unapparent to the average person and can only be detected with veterinary medical screening. This booklet is intended to provide information about the potential health problems associated with various purebred dogs. Directory Section I A list of 182 more commonly known purebred dog breeds, each of which is accompanied by a number or series of numbers that correspond to the congenital and heritable diseases identified and described in Section II. Section II An alphabetical listing of congenital and genetically transmitted diseases that occur in purebred dogs. Each disease is assigned an identification number, and some diseases are followed by the names of the breeds known to be subject to those diseases. How to use this book: Refer to Section I to find the congenital and genetically transmitted diseases associated with a breed or breeds in which you are interested. Refer to Section II to find the names and definitions of those diseases.