What Do Beaver Eat?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acer Rubrum ‘Red Sunset’ ‘Red Sunset’ Red Maple1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-47 November 1993 Acer rubrum ‘Red Sunset’ ‘Red Sunset’ Red Maple1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION ‘Red Sunset’ and ‘October Glory’ have proven to be the best cultivars of Red Maple for the south (Fig. 1). ‘Red Sunset’ has strong wood and is a vigorous, fast-grower, reaching a height of 50 feet with a spread of 25 to 35 feet. Trees are often seen shorter in the southern part of its range unless located on a wet site. This tree is preferred over Red Maple, Silver Maple or Boxelder when a fast-growing maple is needed, and will take on a pyramidal or oval silhouette. The newly emerging red flowers and fruits signal that spring has come. They appear in December and January in Florida, later in the northern part of its range. Leaves retain an attractive high gloss throughout the growing season. The seeds of ‘Red Sunset’ Red Maple are quite popular with squirrels and birds. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Acer rubrum ‘Red Sunset’ Pronunciation: AY-ser ROO-brum Common name(s): ‘Red Sunset’ Red Maple Family: Aceraceae Figure 1. Middle-aged ‘Red Sunset’ Red Maple. USDA hardiness zones: 4B through 8 (Fig. 2) Origin: native to North America DESCRIPTION Uses: Bonsai; wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); Height: 45 to 50 feet recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or Spread: 25 to 40 feet for median strip plantings in the highway; near a deck Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a or patio; reclamation plant; screen; shade tree; regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more specimen; residential street tree or less identical crown forms Availability: generally available in many areas within Crown shape: oval; upright its hardiness range Crown density: moderate 1. -

Beaver (Castor Canadensis) Impacts on Herbaceous and Woody Vegetation in Southeastern Georgia

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Fall 2005 Beaver (Castor Canadensis) Impacts on Herbaceous and Woody Vegetation in Southeastern Georgia Jessica R. Brzyski Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Brzyski, Jessica R., "Beaver (Castor Canadensis) Impacts on Herbaceous and Woody Vegetation in Southeastern Georgia" (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 707. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/707 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEAVER (CASTOR CANADENSIS) IMPACTS ON HERBACEOUS AND WOODY VEGETATION IN SOUTHEASTERN GEORGIA by JESSICA R. BRZYSKI (Under the direction of Bruce A. Schulte) ABSTRACT North American beavers are considered ecosystem engineers. Their activities can quickly and drastically alter habitat properties and perhaps permit highly aggressive colonizing plants, notably non-native species, to invade and potentially dominate. This study examined if beavers in southeastern Georgia have an effect on the terrestrial plant community. Sampling areas included beaver modified (N=9) and nearby but relatively non-impacted riparian habitat (N=9) in a matched pairs design. Vegetation surveys were performed in spring and summer. Species richness was calculated for herbs, vines, woody seedlings, and woody vegetation. Richness of herbaceous vegetation was higher at distances closer to shore while richness of large woody vegetation increased with distance from shore. -

Red Maple 15 Gal $72.00 Acer Rubrum

15 Gallon Trees (scroll down for 25 Gal trees) Acer rubrum - 'Autumn Fantasy' Red Maple 15 Gal $72.00 Acer rubrum – 'Red Sunset' Red Maple 15 Gal $72.00 Acer rubrum – 'Sun Valley' Red Maple 15 Gal $72.00 Acer x freemanii - 'Armstrong' Maple 15 Gal $72.00 Acer x freemanii - 'Autumn Blaze' 15 Gal $72.00 Acer x freemanii - 'Sienna' Sienna Glen Maple 15 Gal $72.00 Betula nigra - 'Dura Heat' Riverbirch 15 Gal $72.00 Carpinus betulus - 'Fastigiata' Euro Hornbeam 15 Gal (low branch) $72.00 Cercis canadensis - Eastern Redbud STD 15gl $72.00 Cercis canadensis - Eastern Redbud 15gl $72.00 Chionanthus virginicus - Chinese Fringe tree 15gl $72.00 Cornus florida - White flowering dogwood 15gl $72.00 X cupressocyparis leylandii - 'Leyland' 15 Gal $72.00 Gleditsia triacanthos - 'Shademaster' Honey Locust 15gl $72.00 Hydrangea tardiva 15gl $72.00 Ilex x Nellie R Stevens Holly 15 Gal $72.00 Lagerstroemia -Muskogee 15 Gal $72.00 Lagerstroemia - Natchez 15 Gal $72.00 Malus 'Prariefire' 15gl $72.00 Malus 'Profusion' 15gl $72.00 Malus 'Starlite' 15gl $72.00 Magnolia Virginiana - Sweetbay magnolia 15gl $72.00 Ostrya virginiana - Hophornbeam 15 Gal $72.00 Platanus occidentalis - American Sycamore 15 Gal $72.00 Platanus x acerfolia - 'Bloodgood' London Planetree 15 Gal $72.00 Platanus x acerfolia - 'Exclaimation' London Planetree 15 Gal $72.00 Prunus cerasifera - 'Krauter Vesuvius'' Plum 15gl $72.00 Prunus cerasifera - 'Newport' Plum 15gl $72.00 Prunus virginiana - 'Canada Red' Cherry 15 Gal $72.00 Prunus x incamp - 'Okame' Cherry 15 Gal $72.00 Prunus x snofozam -

Red Maple (Acer Rubrum) Plant Family: Aceraceae

BWSR Featured Plant Name: Red Maple (Acer rubrum) Plant Family: Aceraceae Statewide Wetland Acer rubrum is hard to miss in the fall landscape Indicator Status: with its bright red fall color. Blooming from FAC April to May and growing up to 90 feet tall, this native tree provides habitat in moist forests for cavity nesters like wood ducks, woodpeckers, and chickadees and is an important early season source of pollen and nectar for pollinators. The species also plays an important role in stabilizing soils along rivers and streams. Red maple, fall color Red female flowers above and Identification newly developing seeds below Gray bark, rounded buds and simple, opposite leaves aid in the identification of red maple. It tends to have a relativley open growth form with main branches that are closer to the ground than many other tree species. Its leaves are around four inches long, palmate, with three shallow lobes and five main veins radiating from the base. Its red or yellowish flowers bloom early in the spring before the leaves develop. When it matures in early summer, the red, yellow or reddish-brown samaras are distributed by wind and root easily by a large taproot, followed by smaller lateral roots. Range In the Eastern Deciduous Forest, red maple is one of the most successful species due to aggressive seeding and an ability to tolerant a wide variety of site conditions. Red maple prefers wet sites such as floodplains, river valleys, swamps, forested bogs, and wooded bluffs. However, the species is widespread throughout Minnesota and North America, from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia south to Texas and east to Florida. -

Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees

Selecting juglone-tolerant plants Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can be very attractive in the home landscape when grown as shade trees, reaching a potential height of 100 feet. The walnuts they produce are a food source for squirrels, other wildlife and people as well. However, whether a black walnut tree already exists on your property or you are considering planting one, be aware that black walnuts produce juglone. This is a natural but toxic chemical they produce to reduce competition for resources from other plants. This natural self-defense mechanism can be harmful to nearby plants causing “walnut wilt.” Having a walnut tree in your landscape, however, certainly does not mean the landscape will be barren. Not all plants are sensitive to juglone. Many trees, vines, shrubs, ground covers, annuals and perennials will grow and even thrive in close proximity to a walnut tree. Production and Effect of Juglone Toxicity Juglone, which occurs in all parts of the black walnut tree, can affect other plants by several means: Stems Through root contact Leaves Through leakage or decay in the soil Through falling and decaying leaves When rain leaches and drips juglone from leaves Nuts and hulls and branches onto plants below. Juglone is most concentrated in the buds, nut hulls and All parts of the black walnut tree produce roots and, to a lesser degree, in leaves and stems. Plants toxic juglone to varying degrees. located beneath the canopy of walnut trees are most at risk. In general, the toxic zone around a mature walnut tree is within 50 to 60 feet of the trunk, but can extend to 80 feet. -

(LONICERA MAACKII) COMPARED to OTHER WOODY SPECIES By

ABSTRACT BEAVER (CASTOR CANADENSIS) ELECTIVITY FOR AMUR HONEYSUCKLE (LONICERA MAACKII) COMPARED TO OTHER WOODY SPECIES by Janet L. Deardorff The North American beaver is a keystone riparian obligate which creates and maintains riparian areas by building dams. In much of the eastern U.S., invasive shrubs are common in riparian zones, but we do not know if beavers promote or inhibit these invasions. I investigated whether beavers use the invasive shrub, Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), preferentially compared to other woody species and the causes of differences in L. maackii electivity among sites. At eight sites, I identified woody stems on transects, recording stem diameter, distance to the water’s edge, and whether the stem was cut by beaver. To determine predictors of cutting by beaver, I conducted binomial generalized regressions, using distance from the water’s edge, diameter, and plant genus as fixed factors and site as a random factor. To quantify beaver preference, I calculated an electivity index (Ei) for each genus at each site. Lonicera maackii was only preferred at two of the eight sites though it comprised 41% of the total cut stems. Stems that were closer to the water’s edge and with a smaller diameter had a higher probability of being cut. Among sites, L. maackii electivity was negatively associated with the density of stems of preferred genera. BEAVER (CASTOR CANADENSIS) ELECTIVITY FOR AMUR HONEYSUCKLE (LONICERA MAACKII) COMPARED TO OTHER WOODY SPECIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science by Janet L. -

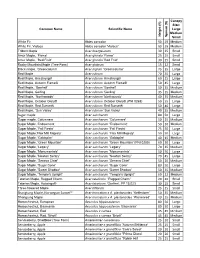

Desirable Street Tree List (PDF)

Canopy Size: Common Name Scientific Name Large Medium Height (ft) Spread (ft) Small White Fir Abies concolor 50 25 Medium White Fir, Violaca Abies concolor 'Violaca' 50 25 Medium Trident Maple Acer buergeianum 30 25 Small Amur Maple, `Flame' Acer ginnala` Flame' 25 25 Small Amur Maple, `Red Fruit' Acer ginnala `Red Fruit' 30 25 Small Rocky Mountain Maple (Tree Form) Acer glabrum 15 12 Small Black maple, 'Greencolumn' Acer nigrum 'Greencolumn' 75 35 Large Red Maple Acer rubrum 70 35 Large Red Maple, Armstrong® Acer rubrum Armstrong® 60 25 Large Red Maple, Autumn Flame® Acer rubrum Autumn Flame® 50 45 Large Red Maple, `Bowhall' Acer rubrum ' Bowhall' 50 15 Medium Red Maple, Gerling Acer rubrum 'Gerling' 35 35 Medium Red Maple, `Northwoods' Acer rubrum 'Northwoods ' 40 35 Medium Red Maple, October Glory® Acer rubrum October Glory® (PNI 0268) 50 35 Large Red Maple, Red Sunset® Acer rubrum Red Sunset® 50 40 Large Red Maple, `Sun Valley' Acer rubrum ' Sun Valley' 40 35 Medium Sugar maple Acer saccharum 80 50 Large Sugar maple, Columnare Acer saccharum ' Columnare' 50 25 Medium Sugar Maple, Endowment Acer saccharum ' Endowment' 50 10 Medium Sugar Maple, 'Fall Fiesta' Acer saccharum ' Fall Fiesta' 75 50 Large Sugar Maple,'Flax Mill Majesty' Acer saccharum ' Flax Mill Majesty' 50 50 Large Sugar Maple, 'Goldspire' Acer saccharum ' Goldspire' 40 15 Medium Sugar Maple, 'Green Mountain' Acer saccharum ' Green Mountain' (PNI 0285) 60 30 Large Sugar Maple, 'Legacy' Acer saccharum 'Legacy' 70 35 Medium Sugar Maple, 'Monumentale' Acer saccharum 'Monumentale' -

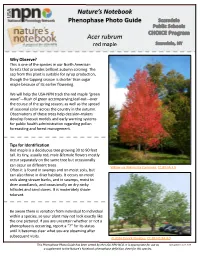

Nature's Notebook Phenophase Photo Guide Acer Rubrum

Nature’s Notebook Phenophase Photo Guide Acer rubrum red maple Why Observe? This is one of the species in our North American forests that provides brilliant autumn coloring. The sap from this plant is suitable for syrup production, though the tapping season is shorter than sugar maple because of its earlier flowering. We will help the USA-NPN track the red maple “green wave”—flush of green accompanying leaf-out–-over the course of the spring season, as well as the spread of seasonal color across the country in the autumn. Observations of these trees help decision-makers develop forecast models and early warning systems for public health administration regarding pollen forecasting and forest management. Tips for Identification Red maple is a deciduous tree growing 30 to 90 feet tall. Its tiny, usually red, male &female flowers mostly occur separately on the same tree but occasionally can occur on different trees. Willow via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0 Often it is found in swamps and on moist soils, but can also thrive in drier habitats. It occurs on moist soils along stream banks, and in swamps, moist to drier woodlands, and occasionally on dry rocky hillsides and sand dunes. It is moderately shade- tolerant. Be aware there is variation from individual to individual within a species, so your plant may not look exactly like the one pictured. If you are uncertain whether or not a phenophase is occurring, report a “?” for its status until it becomes clear what you are observing after subsequent visits. © 2016 Patrick Phoebus. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 This Phenophase Photo Guide has been vetted by the USA-NPN NCO. -

Elemental Concentrations in Foliage of Red Maple, Red Oak, and White

ELEMENTAL CONCENTRATIONS IN FOLIAGE OF RED MAPLE, RED OAK, AND WHITE OAK IN RELATION TO ATMOSPHERIC DEPOSITION IN PENNSYLVANIA D. D. Davis, J. M. Skelly, and B. L. Nash' Abstract: Foliage was sampled in June and late August-early September in 1988 and 1989 from the outer crowns of codominant red maple (Acer rubrum L.), northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.), and white oak (Q. alba L.) trees in forest stands along an atmospheric deposition gradient in north-central Pennsylvania. Leaf samples from approximately 480 trees were analyzed for concentration of macroelements N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and S, as well as microelements Al, B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Na, Pb, Si, Sr, V and Zn. Foliar concentrations of Fe, S, and Sr were generally greater in the high deposition portion of the gradient. Concentrations of other foliar elements generally were not related to the spatial pattern of atmospheric input. INTRODUCTION Concentrations of specific elements (e.g. sulfur and trace elements) in plant tissue have been used to indicate the magnitude of atmospheric pollutant input to forest ecosystems. Several studies have been conducted in the oak forests of Pennsylvania USA which indicate that certain elements accumulate in plant tissues subjected to elevated pollution levels. For example, the sulfur content of tree foliage in woodlands of western Pennsylvania was related to distance and direction from a complex of large coal-fired power plants (Hutnik and others, 1989). Strontium concentrations of white oak (Quercus alba L.) xylem in a mixed-oak forest of central Pennsylvania were related to distance from a small coal-fired power plant (Long and Davis, 1989). -

Red Maple Tree

M* The Important Distinctions E L Red Maple Sugar Maple Silver Maple P Acer rubrum Acer saccharum Acer saccharinum A BARK M Older trees: ridged and broken Older trees: rough and deeply Older trees: somewhat furrowed, TEXTURE into plate like scales. furrowed. Young trees: smooth separates into thin plates. Young trees: smooth. and slightly fissured. Young trees: smooth. Dark gray on older trunks, Gray on older trunks, Dark gray on older trunks, COLOR light gray on young trees light gray on young trees gray on young trees LEAVES 3–5 lobes. sides of terminal lobe 3–5 lobes, sinuous, sides of 5 lobes, rarely 3; lobes long and LOBES/SHAPE converge, notches between lobes terminal lobes flare outward, narrow like fingers on a hand V-shaped notches between lobes rounded MARGIN Irregularly doubly toothed Sparsely toothed Irregularly and sharply toothed SURFACE Under-surface slightly white Under-surface pale green Under-surface silvery white FLOWER Scarlet or yellow-red, appears Greenish-yellow, appears with Greenish-yellow or pinkish, APPEARANCE before the leaves the leaves appears long before the leaves BUDS 1 1 1 LENGTH Terminal bud— ⁄8 inch Terminal bud— ⁄4 inch Terminal bud— ⁄8 inch Blunt-pointed, as long Sharp-pointed, many SHAPE Blunt-pointed, slightly ridged as broad scales showing COLOR Dark red Purplish-brown to gray Bright red above, green below FRUIT Paired, but with SHAPE Paired, slightly divergent Paired and slightly divergent one usually abortive SEED BODY Oval in outline Round Football-shaped 3 Strongly divergent, WING Reddish; -

R M Acer Rubrum L

R M Acer rubrum L. ed maple—also known as soft, R white or swamp maple—occurs throughout the state. A rapid grower and the most abundant of the maples, it is typically found in swamps and poorly drained sites, but also occurs elsewhere. The red maple is a medium- sized, slender tree that becomes 50–60 feet high, and 1–2 feet in diameter. The branches are upright, forming a somewhat narrow head. Usually the trunk is not divided. The bark on young trees is smooth and light gray. On old trunks, it is dark gray, ridged and broken into plate- like scales. 72 RED MAPLE E L P A M Red maples produce bright red flowers followed by abundant seeds in the springtime. The leaves are opposite, 3–5 inch- The fruit is winged, ripens in es long, with 3–5 lobes and margins spring or early summer, and germi- that are irregularly double-toothed. nates as soon as it falls. Wings are only The upper surface is light green; lower slightly divergent, about ¾ inch long. surface is white. The sides of the termi- The seed body lacks a depression. nal lobe converge toward the tip; and The twigs are straight, stiff, do not the notches between lobes are V- have a rank odor when broken, and are shaped. In fall, the leaves turn scarlet red on both surfaces. Buds are red and and orange. often clustered. The flowers are produced in clus- The wood is close-grained, heavy, ters on stalks before leaf buds open. moderately strong, easily worked but Males are yellowish-red while females not durable, although it will take a are bright scarlet. -

Acer Rubrum 'Somerset' and 'Sun Valley'

Acer rubrum 'Somerset' and 'Sun Valley' The U.S. National Arboretum presents 'Somerset' and 'Sun Valley' red maples, two additional selections from the U.S. National Arboretum red maple research evaluation program. Showing excellent, long-lasting red fall color, tolerance to potato leafhopper, and symmetrical form, these male selections will fill important niches in the nursery industry and in the landscape. 'Somerset' 'Sun Valley' U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 3501 New York Ave., N.E., Washington, DC 20002 'Somerset' and 'Sun Valley' Red Maple Botanical Name: Acer rubrum L. 'Somerset' (NA 59905; PI 583791) Acer rubrum L. 'Sun Valley' (NA 59906; PI 583790) Family: Aceraceae Hardiness: U.S.D.A. Zones 4–7; 'Somerset' to Zone 8. Development: 'Somerset' and 'Sun Valley' resulted from controlled crosses made in 1982 by A.M. Townsend as part of a tree genetics research project examining the inheritance of fall color and leafhopper resistance. 'Somerset' is a cross of Acer rubrum 'October Glory' and A. rubrum 'Autumn Flame'. 'Sun Valley' is a cross of A. rubrum 'Red Sunset' and A. rubrum 'Autumn Flame'. Released December, 1994. Significance: 'Somerset' and 'Sun Valley' are red maple cultivars with exceptional, long- lasting red fall color and significant levels of tolerance to potato leafhopper— better than or comparable to many commercially available red maple cultivars in long-term tests in Maryland and Ohio. 'Somerset' appears to color well as far south as Georgia. Description: Height and Width: 'Somerset': 23 feet tall, 11 foot crown spread at 12 years.