The Heritization of Bulgarian Rose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Bulgaria

Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Bulgaria By Henry L. deZeng IV General Map Edition: November 2014 Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Copyright © by Henry L. deZeng IV (Work in Progress). (1st Draft 2014) Blanket permission is granted by the author to researchers to extract information from this publication for their personal use in accordance with the generally accepted definition of fair use laws. Otherwise, the following applies: All rights reserved. No part of this publication, an original work by the authors, may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the author. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. This information is provided on an "as is" basis without condition apart from making an acknowledgement of authorship. Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Airfields Bulgaria Introduction Conventions 1. For the purpose of this reference work, “Bulgaria” generally means the territory belonging to the country on 6 April 1941, the date of the German invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia and Greece. The territory occupied and acquired by Bulgaria after that date is not included. 2. All spellings are as they appear in wartime German documents with the addition of alternate spellings where known. Place names in the Cyrillic alphabet as used in the Bulgarian language have been transliterated into the English equivalent as they appear on Google Earth. 3. It is strongly recommended that researchers use the search function because each airfield and place name has alternate spellings, sometimes 3 or 4. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

Regional Cluster Landscape Republic of Bulgaria

Project co-funded by European Union funds (ERDF, IPA) Regional cluster landscape Republic of Bulgaria WP3 Value Chain Mapping Activity 3.2 Cluster Mapping Output 3.2 Cluster Mapping as an Analytical Tool D3.2.1 Regional cluster landscapes and one entire cluster landscape for Danube Region Cross-clustering partnership for boosting eco-innovation by developing a joint bio-based value-added network for the Danube Region Project co-funded by European Union funds (ERDF, IPA) CONTENTS Cluster Mapping Fact Sheets .................................................................................................................. 3 Eco-Construction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Phytopharma .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bio-based Packaging ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Cluster Mapping/Bulgaria 2 Project co-funded by European Union funds (ERDF, IPA) CLuster MappinG FaCt sheets In the following the cluster mapping results of and Phytopharmaceuticals are presented. Besides selected clusters and cluster initiatives in Bulgaria in the mapping as such, additional informations are the field of Eco-Construction, Bio-based Packaging given about age, size, key objectives etc. ECO-CONSTRUCTION There is no cluster -

District Doings Gretchen Humphrey, PNW District Director

‘Catherine Graham’ Hybrid Tea Photo by Rich Baer In This Issue District Doings Gretchen Humphrey, PNW District Director You can email me at: [email protected] or call me at 503-539-6853 Message From the Director————— 1-2 District Horticulture Judging News—— 2-3 District CR Report—--———––——–- 3-4 Happy New Year to Everyone! District Show (Tri-City Rose Society)— 4 As we roll into a new year and a new growing season, I am excited to see what is Rose Science: Stomata: in store for us in the great Pacific Northwest. Windows to the Outside World-——– 5-6 Prizes and Awards ———————–- 7 Since our last newsletter, my husband and I traveled to the ARS National Con- Roses In Review————————— 8-9 vention in Tyler, Texas. This whirlwind weekend began with the Board Meeting on Rose Arrangement Workshop———– 10 Thursday, taking care of important ARS business. Following that was the Rose Show, Rose Arrangement School————— 11 held at the Rose Center in Tyler. This time, we didn’t bring any roses, since it was the Coming Events/Rose Show Dates—— 11 middle of October. Although that month was particularly dry, the timing of our blooms was off, and we didn’t have any worthy specimens. Old Garden Roses: The National Rose Show was rather small, although there were some beautiful What Are They?—–—————– 12-16 blooms, and some varieties we hadn’t seen before. After judging, we volunteered to guide Hybrid Gallicas——— 12-13 Damasks—————– 13-14 the busloads of visitors around the show. It turned out there weren’t that many on Friday, Albas——————— 14 but we did manage to greet a few nice folks. -

Bulgaria ‐ Balkan Legends Sofia, Veliko Tarnovo, Kazanlak, Koprivshtitsa 8 Days / 7 Nights

Bulgaria ‐ Balkan Legends Sofia, Veliko Tarnovo, Kazanlak, Koprivshtitsa 8 days / 7 Nights Rental Car The program includes 7 nights BB basis in 3‐star hotel – 3 nights in Sofia, 2 nights in Veliko Tarnovo or Arbanasi, 1 night in Kazanlak or surroundings, 1 night in Koprivshtitsa; rental car for the whole period. PROGRAM DAY 1: ARRIVAL AT THE SOFIA AIRPORT. Meeting at Sofia airport by a representative who will supply the clients with a map of Bulgaria, a map of Sofia and some documentation about the trip. Pick up the rental car. Overnight stay in Sofia. DAY 2: BREAKFAST. DEPARTURE FOR VELIKO TARNOVO. On the way a visit to the Troyan Monastery ‐ the third biggest monastery in Bulgaria, founded in the 17th century. In 1847 the monks requested that the famous Bulgarian artist Zahari Zograf work on the decoration of the monastery. Late afternoon – arrival in Veliko Tarnovo – the capital of the Second Bulgarian Empire (1187‐1396). Overnight stay in Veliko Tarnovo or Arbanasi. DAY 3: BREAKFAST. SIGHTSEEING TOUR OF VELIKO TARNOVO. A visit to the historical village of Arbanasi ‐ the Konstantsaliev’s House – one of the biggest and most lavishly decorated houses of the Bulgarian National Revival and at the Church of the Nativity of Christ, the oldest church in Arbanasi, unique with its frescoes. Return to Veliko Tarnovo. Overnight stay in Veliko Tarnovo or Arbanasi. • 7 Mezher Street, Antelias • 60‐233 Beirut, Lebanon • +961 4 712037 www.ventnouveau.com • [email protected] DAY 4: BREAKFAST. DEPARTURE FOR KAZANLAK. A visit to Dryanovo Monastery, established in the 13th century and situated in the picturesque gorge of Dryanovo River. -

BULGARIA DISCOVERED GUIDE on the Cover: Lazarka, 46/55 Oils Cardboard, Nencho D

Education and Culture DG Lifelong Learning Programme BULGARIA DISCOVERED GUIDE On the cover: Lazarka, 46/55 Oils Cardboard, Nencho D. Bakalski Lazarka, this name is given to little girls, participating in the rituals on “Lazarovden” – a celebration dedicated to nature and life’ s rebirth. The name Lazarisa symbol of health and long life. On the last Saturday before Easter all Lazarki go around the village, enter in every house and sing songs to each family member. There is a different song for the lass, the lad, the girl, the child, the host, the shepherd, the ploughman This tradition can be seen only in Bulgaria. Nencho D. BAKALSKI is a Bulgarian artist, born in September 1963 in Stara Zagora. He works in the field of painting, portraits, iconography, designing and vanguard. He is a member of the Bulgarian Union of Artists, the branch of Stara Zagora. Education and Culture DG Lifelong Learning Programme BULGARIA DISCOVERED GUIDE 2010 Human Resource Development Centre 2 Rachenitsa! The sound of bagpipe filled the air. The crowd stood still in expectation. Posing for a while against each other, the dancers jumped simultaneously. Dabaka moved with dexterity to Christina. She gently ran on her toes passing by him. Both looked at each other from head to toe as if wanting to show their superiority and continued their dance. Christina waved her white hand- kerchief, swayed her white neck like a swan and gently floated in the vortex of sound, created by the merry bagpipe. Her face turned hot… Dabaka was in complete trance. With hands freely crossed on his back he moved like a deer performing wondrous jumps in front of her … Then, shaking his head to let the heavy sweat drops fall from his face, he made a movement as if retreating. -

Physico-Chemical Analysis and Determination of Various Chemical Constituents of Essential Oil in Rosa Centifolia

Pak. J. Bot., 41(2): 615-620, 2009. PHYSICO-CHEMICAL ANALYSIS AND DETERMINATION OF VARIOUS CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS OF ESSENTIAL OIL IN ROSA CENTIFOLIA M. KHALID SHABBIR1, RAZIYA NADEEM1, HAMID MUKHTAR2, FAROOQ ANWAR1 AND MUHAMMAD W. MUMTAZ1, 1Department of Chemistry, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan 2Institute of Industrial Biotechnology, Govt. College University, Lahore 54000 Pakistan, 3Department of Chemistry, University of Gujrat, Pakistan Abstract This paper reports the isolation and characterization of essential oil of Rosa centifolia. The oil was extracted from freshly collected flower petals of R. centifolia with petroleum ether using Soxhlet apparatus. Rosa centifolia showed 0.225% concrete oil and 0.128% yield of absolute oil. Some physico-chemical properties of the extracted oil like colour, refractive index, congealing point, optical rotation, specific gravity, acid number and ester number were determined and were found to be yellowish brown, 1.454 at 340C, 15°C, -32.50 to +54.21, 0.823 at 30oC, 14.10245 and 28.1876. High- resolution gas liquid chromatographic (HR-GLC) analysis of the essential oil of R. centifolia, showed the phenethyl alcohol, geranyl acetate, geraniol and linalool as major components whereas, benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde and citronellyl acetate were detected at trace levels. Introduction A variety of roses are generally cultivated for home and garden beautification in many parts of the world. Its rich fragrance has perfumed human history for generations (Rose, 1999). Roses contain very little essential oil but it has a wide range of applications in many industries for the scenting and flavouring purposes. It is used as perfumer in soap and cosmetics and as a flavor in tea and liquors. -

Download Tour Description

Balkan Trails S.R.L. 29 Mihail Sebastian St. 050784 Bucharest, Romania Tour operator license #757 Bulgaria at a glance (4 nights) Tour Description: In this beautifully curated, compact tour, discover the essentials of old Bulgaria: historic architecture, vibrant traditional arts and crafts, sweeping panoramic vistas, medieval monasteries and fortresses, and traces of Roman and Thracian culture. Begin your tour in the vibrant Bulgarian capital of Sofia, where you’ll stroll along the famed yellow-paved streets to explore major landmarks such as the Aleksandar Nevski Cathedral and the covered food market. At the 11th-century Boyana Church (UNESCO World Heritage Site), explore the priceless treasures at your leisure. Drive into the mountains to the Bulgarian Orthodox Rila Monastery, built a full 1147 meters above sea level. In the picturesque, artistic Plovdiv, tour the Old Town, Antique Theater, and Roman Stadium. In Kazanlak, home of Bulgarian rose oil more valuable than gold, visit the celebrated UNESCO World Heritage, 4th- century B.C. Thracian Tomb. On the way to Veliko Tarnovo, drive through the breathtaking Shipka Pass, site of the final Bulgarian victory over the Ottoman Turks. Visit the soaring Tsarevets Fortress, and take in the spectacular view of the Old Town. Explore Samovodene Street, a mecca for folkloric Bulgarian arts and crafts. Next, visit the architecturally significant village of Arbanassi. Tour Konstantsalieva House, where you’ll explore the daily realities of a well-to-do 17th-century family. You will also explore the Nativity Church, built at a time when Christian architecture in Bulgaria was subject to restrictions imposed by the Ottoman Turks. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

CHAPTER 14 Choral Societies and National Mobilization in Nineteenth-Century Bulgaria Ivanka Vlaeva Compared with the histories of many national movements in nineteenth- century Europe, in Bulgaria the industrial revolution was delayed and mod- ern culture arrived late. Lagging behind most other Europeans, the Bulgarian population had to compensate for its lack of modern cultural development. Thus, one important characteristic of Bulgarian culture is its evolution at accelerated rates. Before liberation in 1878, for almost five centuries the Bulgarian lands were under Ottoman rule, without their own governmental and religious institu- tions. Foreign rule, a feudal economy, a weak middle class, and the absence of national cultural institutions were serious obstacles to the development of a new culture on the western European model. The most important aims for the Bulgarians (led by educators, intellectuals, and revolutionists) were to struggle politically against Ottoman governance, economically for new industrial pro- cesses in the Ottoman Empire, and culturally for a national identity. The lead- ers of the revolutionary movement called for a struggle not against the Turkish people, but against Ottoman rulers and foreign clerks.1 These historical processes resemble those elsewhere in Europe, especially in the central and southeastern regions. Nineteenth-century Bulgarian culture therefore needs to be considered along with that of the Balkans more gener- ally because of the cultural similarities, interactions, and fluctuations in this region.2 The establishment of a new economy and the fight for modern educa- tion were among the main priorities in Bulgarian communities. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are the so-called Revival period in Bulgarian cultural development, strongly influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment. -

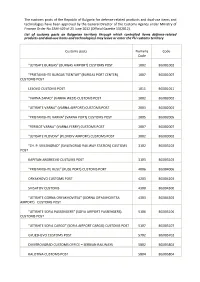

The Customs Posts of the Republic of Bulgaria for Defence-Related

The customs posts of the Republic of Bulgaria for defence-related products and dual-use items and technologies have been approved by the General Director of the Customs Agency under Ministry of Finance Order No ZAM-429 of 25 June 2012 (Official Gazette 53/2012). List of customs posts on Bulgarian territory through which controlled items defence-related products and dual-use items and technologies) may leave or enter the EU customs territory Customs posts Numeric Code Code “LETISHTE BURGAS” (BURGAS AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 1002 BG001002 “PRISTANISHTE BURGAS TSENTAR” (BURGAS PORT CENTER) 1007 BG001007 CUSTOMS POST LESOVO CUSTOMS POST 1011 BG001011 “VARNA ZAPAD” (VARNA WEST) CUSTOMS POST 2002 BG002002 “LETISHTE VARNA” (VARNA AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 2003 BG002003 “PRISTANISHTE VARNA” (VARNA PORT) CUSTOMS POST 2005 BG002005 “FERIBOT VARNA” (VARNA FERRY) CUSTOMS POST 2007 BG002007 “LETISHTE PLOVDIV” (PLOVDIV AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST 3002 BG003002 “ZH. P. SVILENGRAD” (SVILENGRAD RAILWAY STATION) CUSTOMS 3102 BG003102 POST KAPITAN ANDREEVO CUSTUMS POST 3103 BG003103 “PRISTANISHTE RUSE” (RUSE PORT) CUSTOMS PORT 4006 BG004006 ORYAKHOVO CUSTOMS POST 4203 BG004203 SVISHTOV CUSTOMS 4300 BG004300 “LETISHTE GORNA ORYAKHOVITSA” (GORNA ORYAKHOVITSA 4303 BG004303 AIRPORT) CUSTOMS POST “LETISHTE SOFIA PASSENGERS” (SOFIA AIRPORT PASSENGERS) 5106 BG005106 CUSTOMS POST “LETISHTE SOFIA CARGO” (SOFIA AIRPORT CARGO) CUSTOMS POST 5107 BG005107 GYUESHEVO CUSTOMS POST 5702 BG005702 DIMITROVGRAD CUSTOMS OFFICE – SERBIAN RAILWAYS 5802 BG005802 KALOTINA CUSTOMS POST 5804 BG005804 -

Evaluation of Essential Oils and Extracts of Rose Geranium and Rose Petals As Natural Preservatives in Terms of Toxicity, Antimicrobial, and Antiviral Activity

pathogens Article Evaluation of Essential Oils and Extracts of Rose Geranium and Rose Petals as Natural Preservatives in Terms of Toxicity, Antimicrobial, and Antiviral Activity Chrysa Androutsopoulou 1, Spyridoula D. Christopoulou 2, Panagiotis Hahalis 3, Chrysoula Kotsalou 1, Fotini N. Lamari 2 and Apostolos Vantarakis 1,* 1 Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece; [email protected] (C.A.); [email protected] (C.K.) 2 Laboratory of Pharmacognosy & Chemistry of Natural Products, Department of Pharmacy, University of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece; [email protected] (S.D.C.); [email protected] (F.N.L.) 3 Tentoura Castro-G.P. Hahalis Distillery, 26225 Patras, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Essential oils (EOs) and extracts of rose geranium (Pelargonium graveolens) and petals of rose (Rosa damascena) have been fully characterized in terms of composition, safety, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties. They were analyzed against Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus, Aspergillus niger, and Adenovirus 35. Their toxicity and life span were also determined. EO of P. graveolens (5%) did not retain any antibacterial activity (whereas at Citation: Androutsopoulou, C.; 100% it was greatly effective against E. coli), had antifungal activity against A. niger, and significant Christopoulou, S.D.; Hahalis, P.; antiviral activity. Rose geranium extract (dilutions 25−90%) (v/v) had antifungal and antibacterial Kotsalou, C.; Lamari, F.N.; Vantarakis, activity, especially against E. coli, and dose-dependent antiviral activity. Rose petals EO (5%) retains A. Evaluation of Essential Oils and low inhibitory activity against S. aureus and S. Typhimurium growth (about 20−30%), antifungal Extracts of Rose Geranium and Rose activity, and antiviral activity for medium to low virus concentrations. -

ANALYSIS of the CHILD PROTECTION SYSTEM in BULGARIA © UNICEF/UNI154434/Pirozzi

ANALYSIS OF THE CHILD PROTECTION SYSTEM IN BULGARIA © UNICEF/UNI154434/Pirozzi Final report October 2019 This report has been prepared with the financial assistance of UNICEF in Bulgaria under the Contract LRPS- 2018- 9140553 dated 19 of September 2018. The views expressed herein are those of the consultants and therefore in no way reflect the of- ficial opinion of UNICEF. The research was carried out by a consortium of the companies Fresno, the Right Link and PMG Analytics. The research had been coordinated by Milena Harizanova, Daniela Koleva and Dessislava Encheva from the UNICEF office in Sofia, Bulgaria. Elaborated with the technical assistance of Authors. José Manuel Fresno (Team Leader) Roberta Cecchetti (International Child Protection Expert) Philip Gounev (Public Management Expert) Martin Gramatikov (Legal Expert) Slavyanka Ivanova (Field Research Coordinator) Stefan Meyer (Research Coordination) Skye Bain (Research assistance and quality assurance) Maria Karayotova (Research assistance) Greta Ivanova Tsekova (Research assistance) Table of Content Abreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Glossary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Executive Summary................................................................................................................ 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................