Rituals for Social Communication in Folk Theatre of Rajasthan with Special Reference to Performance of Jagdev Kankaali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Identity and Difference in a Muslim Community in Central Gujarat, India Following the 2002 Communal Violence

Identity and difference in a Muslim community in central Gujarat, India following the 2002 communal violence Carolyn M. Heitmeyer London School of Economics and Political Science PhD 1 UMI Number: U615304 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615304 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

THE MERCHANT CASTES OF A SMALL TOWN IN RAJASTHAN (a study of business organisation and ideology) CHRISTINE MARGARET COTTAM A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology and Soci ology, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. ProQuest Number: 10672862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Certain recent studies of South Asian entrepreneurial acti vity have suggested that customary social and cultural const raints have prevented positive response to economic develop ment programmes. Constraints including the conservative mentality of the traditional merchant castes, over-attention to custom, ritual and status and the prevalence of the joint family in management structures have been regarded as the main inhibitors of rational economic behaviour, leading to the conclusion that externally-directed development pro grammes cannot be successful without changes in ideology and behaviour. A focus upon the indigenous concepts of the traditional merchant castes of a market town in Rajasthan and their role in organising business behaviour, suggests that the social and cultural factors inhibiting positivejto a presen ted economic opportunity, stimulated in part by external, public sector agencies, are conversely responsible for the dynamism of private enterprise which attracted the attention of the concerned authorities. -

Secularization Without Secularism in Pakistan

Research Questions / Questions de Recherche N°41 – September 2012 Secularization without Secularism in Pakistan Christophe Jaffrelot Centre d’études et de recherches internationales Sciences Po Research Questions / Questions de recherche – n°41 – September 2012 1 http://www.ceri-sciences-po.org/publica/qdr.htm Secularization without Secularism in Pakistan Summary Pakistan was created in 1947 by leaders of the Muslim minority of the British Raj in order to give them a separate state. Islam was defined by its founder, Jinnah, in the frame of his “two-nation theory,” as an identity marker (cultural and territorial). His ideology, therefore, contributed to an original form of secularization, a form that is not taken into account by Charles Taylor in his theory of secularization – that the present text intends to test and supplement. This trajectory of secularization went on a par with a certain form of secularism which, this time, complies with Taylor’s definition. As a result, the first two Constitutions of Pakistan did not define Islam as an official religion and recognized important rights to the minorities. However, Jinnah’s approach was not shared by the Ulema and the fundamentalist leaders, who were in favor of an islamization policy. The pressures they exerted on the political system made an impact in the 1970s, when Z.A. Bhutto was instrumentalizing Islam. Zia’s islamization policy made an even bigger impact on the education system, the judicial system and the fiscal system, at the expense of the minority rights. But Zia pursued a strategy of statization of Islam that had been initiated by Jinnah and Ayub Khan on behalf of different ideologies, which is one more illustration of the existence of an additional form of secularization that has been neglected by Taylor. -

The Baloch of Karachi and the Partition of British India

South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies ISSN: 0085-6401 (Print) 1479-0270 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csas20 Our City, Your Crisis: The Baloch of Karachi and the Partition of British India Adeem Suhail & Ameem Lutfi To cite this article: Adeem Suhail & Ameem Lutfi (2016) Our City, Your Crisis: The Baloch of Karachi and the Partition of British India, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 891-907, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1230966 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2016.1230966 Published online: 13 Oct 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 312 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=csas20 SOUTH ASIA: JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 39, NO. 4, 891–907 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2016.1230966 ARTICLE Our City, Your Crisis: The Baloch of Karachi and the Partition of British India Adeem Suhaila and Ameem Lutfib aDepartment of Anthropology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA; bDepartment of Cultural Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This essay approaches the Partition of British India through the Baloch; cosmopolitanism; perspective of the Baloch inhabitants of Karachi, who locate the city historiography; Indian Ocean; at the centre of diverse political geographies and cultural lineages. Karachi; labour; memory; We specifically look at the testimony of the residents of Karachi’s narrative; oral history; Partition; Sindh historic neighbourhoods of Qiyamahsari and Lyari. Their narratives demonstrate how Partition spelled the end of certain forms of socio- political life in the city, while reaffirming others. -

“Conquest Without Rule: Baloch Portfolio Mercenaries in the Indian Ocean.”

“Conquest without Rule: Baloch Portfolio Mercenaries in the Indian Ocean.” by Ameem Lutfi Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Supervisor ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ David Gilmartin ___________________________ Irene Silverblatt Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT “Conquest without Rule: Baloch Portfolio Mercenaries in the Indian Ocean.” by Ameem Lutfi Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Supervisor ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ David Gilmartin ___________________________ Irene Silverblatt An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ameem Lutfi 2018 Abstract The central question this dissertation engages with is why modern states in the Persian Gulf rely heavily on informal networks of untrained and inexperienced recruits from the region of Balochistan, presently spread across Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The answer, it argues, lies in the longue durée phenomenon of Baloch conquering territories abroad but not ruling in their own -

Debates on Muslim Caste in North India and Pakistan Julien Levesque

Debates on Muslim Caste in North India and Pakistan Julien Levesque To cite this version: Julien Levesque. Debates on Muslim Caste in North India and Pakistan: from colonial ethnography to pasmanda mobilization. 2020. hal-02697381 HAL Id: hal-02697381 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02697381 Preprint submitted on 1 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CSH-IFP Working Papers 15 USR 3330 “Savoirs et Mondes Indiens” DEBATES ON MUSLIM CASTE IN NORTH INDIA AND PAKISTAN: FROM COLONIAL ETHNOGRAPHY TO PASMANDA MOBILIZATION Julien Levesque Institut Français de Pondichéry Centre de Sciences Humaines Pondicherry New Delhi The Institut Français de Pondichéry and the Centre de Sciences Humaines, New Delhi together form the research unit USR 3330 “Savoirs et Mondes Indiens” of the CNRS. Institut Français de Pondichéry (French Institute of Pondicherry): Created in 1955 under the terms agreed to in the Treaty of Cession between the Indian and French governments, the IFP (UMIFRE 21 CNRS- MAE) is a research centre under the joint authority of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MAE) and the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). It fulfills its mission of research, expertise and training in human and social sciences and ecology, in South and South-East Asia. -

Religious Identity and the Provision of Public Goods: Evidence from the Indian Princely States∗

Religious Identity and the Provision of Public Goods: Evidence from the Indian Princely States∗ Latika Chaudharyy Jared Rubinz March 2015 Abstract Identifying the effect of a ruler’s religious identity on policy is challenging because religious identity rarely varies over time and place. We address this problem by ex- ploiting quasi-random variation in the religion of rulers in the Indian Princely States. Using data from the 1911 census, we find that Muslim-ruled states had lower Hindu literacy but the religion of the ruler had no statistically significant impact on Mus- lim literacy, railroad ownership, or post office provision. These results support the hypothesis that rulers provide less public goods when religious institutions provide a substitute targeted at their co-religionists. Keywords: Public Goods, Identity, Religion, Literacy, Railroads, Post Offices, Princely States, India, Islam, Hinduism JEL Codes: H41, H42, N35, H75, I25, Z12 ∗We are grateful to Sheetal Bharat for sharing her data on colonial post offices. We also wish to thank Sascha Becker, Shameel Ahmad, Lakshmi Iyer, Saumitra Jha, Petra Moser and seminar participants at Stanford University, the 2014 Yale South Asian Economic History Conference, the 2014 ASREC, 2013 AEA and 2012 WEAI Conferences for helpful comments. Latika Chaudhary thanks the Hoover Institution for financial support through the National Fellows Program. All errors are our own. yAssociate Professor, Naval Postgraduate School, Email: [email protected] zAssociate Professor, Chapman University, Email: [email protected] 1 Introduction Scholars have long recognized the influence of religion on economic development.1 In recent years the focus has shifted to uncovering specific mechanisms linking the two. -

High Court of Sindh, Karachi Complete List of Applicants Applied for the Post of Civil Judge & Judicial Magistrate, 2016

HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI COMPLETE LIST OF APPLICANTS APPLIED FOR THE POST OF CIVIL JUDGE & JUDICIAL MAGISTRATE, 2016 SNO NAME RNO QUAL. BIRTH DATE ENROL. DATE DOMICILE AND PRC OBJECTIONS REMARKS 1 Aabid Ali B.COM.,LLB 20-JAN-1987 02-FEB-2016 Jamshoro Eligible S/o Mir Muhammad (29 years, 11 months (11 months and 5 days) Jamshoro EMAIL ADDRESS IS REQUIRED. (2016448) and 17 days) 2 Aadil Aziz B.COM, LL.B. 12-FEB-1990 02-FEB-2016 Kamber @Shadadkot Eligible S/o Aziz Ul Haq Solangi (26 years, 10 months (11 months and 5 days) Kamber @Shadadkot (2016757) and 25 days) 3 Aadil Khan M.A, LL.B. 07-FEB-1983 14-MAY-2009 Khairpur Eligible S/o Karam Hussain Rid (33 years and 11 (7 years, 7 months and 23 Khairpur (2016266) months ) days) 4 Aajiz Hussain Solangi B.A.,LLB 01-JAN-1989 01-AUG-2015 Naushero Feroze Eligible S/o Mohammad Juman (28 years and 6 days) (1 year, 5 months and 6 Naushero Feroze Solangi days) (2016403) 5 Aakash Ali Rind B.A.,LLB 05-FEB-1991 08-OCT-2015 Tando Muhammad Khan Eligible S/o Anwer Ali Rind (25 years, 11 months (1 year, 2 months and 29 Tando Muhammad Khan (20161633) and 2 days) days) 6 Aamir Ali B.COM.,LLB 01-JAN-1990 Naushero Feroze Eligible, S/o Ghulam Sarwar (27 years and 6 days) (N/A) Naushero Feroze A.P.S. in N.A.B. COURT (2016703) Appointment Date:08/01/2011 7 Aamir Ali B.SC, LL.B. -

Bahishti Zewar (Translated As Heavenly Ornaments), Was Written by Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanvi Rahmatullahe Alaihe

Bahishti Zewar (translated as Heavenly Ornaments), was written by Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanvi Rahmatullahe Alaihe. is a 8 volume comprehensive handbook of fiqh (jurisprudence), especially for the education of girls and women. This volume has been compiled by the Islamic Bulletin www.islamicbulletin.com into two separate books. Volume 1,2, 3 and the second volume 4,5,6, 7. It describes the Five Pillars of Islam and also highlights more obscure principles. For years it has remained a favorite with the people of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent. Among (Hanafi Deobandi) Muslims, it is a popular practice to present this volume to a new bride. The motivation behind this gesture is that the young woman is taking up a new identity and new life as a wife and mother-to-be. She should be well versed in the rites, rituals and tradition of Islam. Bahishti Zewar Moulana Ashraf Ali Thanwi (Rahmatullah Alaihi) TRUE STORIES First Story Rasulullah sallAllâhu alayhi wa sallam is reported to have said: "A person was in a jungle when all of a sudden he heard a voice in a cloud saying: "Go and water the orchard of so and so person." On hearing that voice, the cloud moved and poured heavily on a stony place. All the water collected in a drain and began to flow. This person began following the water and saw that a man was standing in his orchard and was sprinkling water with a spade. This person asked the gardener: "O servant of Allâh! What is your name?" He gave the same name which this person had heard in the cloud. -

A Historical Overview of Islam in South Asia

Copyrighted Material INTRODUCTION ——— A Historical Overview of Islam in South Asia Barbara D. Metcalf Sri Lanka and the Southern Coasts For long centuries, India, in a memorable phrase, was “on the way to everywhere” (Abu Lughod 1989). Trade brought Arabs to India’s southern seacoasts and to the coasts of Sri Lanka, where small Muslim communities were established at least by the early eighth century. These traders played key economic roles and were pa tronized by non-Muslim kings like the Zamorin of Calicut (Kozhikode) who wel comed diverse merchant communities. The coastal areas had long served as nodal points for the transshipment of high value goods between China, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, in addition to the spices, teak, and sandalwood lo cally produced. The Muslim populations grew through intermarriage, conversion, and the continued influx of traders. The Portuguese, who controlled the Indian Ocean by the early sixteenth cen tury, labeled the Sri Lankan Muslim population “Moro” or “Moors.” Sri Lankan Muslims are still known by this term, whether they are by origin Arabs, locals, Southeast Asians (who came especially during the Dutch dominance from the mid-seventeenth to the end of the eighteenth century) or Tamils from south India (whose numbers increased under the British Crown Colony, 1796–1948). One account of early Islam in Malabar on the southwestern coast is the Qissat Shakarwati Farmad, an anonymous Arabic manuscript whose authenticity may be disputed by contemporary historians but which continues to be popular among the Mapilla (“Moplahs”) of the region. In this account, Muslims claim descent from the Hindu king of Malabar, who was said to have personally witnessed the miracle of the Prophet Muhammad’s splitting of the moon (Friedmann 1975). -

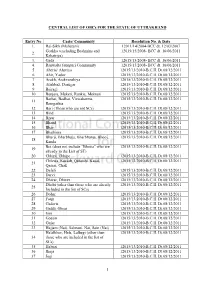

1 CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of UTTRAKHAND Entry No

CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF UTTRAKHAND Entry No Caste/ Community Resolution No. & Date 1. Rai-Sikh (Mahatam) 12011/14/2004-BCC dt. 12/03/2007 Gorkha (excluding Brahmins and 12015/15/2008- BCC dt. 16/06/2011 2. Kshatriya) 3. Gada 12015/15/2008- BCC dt. 16/06/2011 4. Ranwalta Jaunpuri Community 12015/15/2008- BCC dt. 16/06/2011 5 Aheria/ Aheriya 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 6 Ahir, Yadav 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 7 Arakh, Arakvanshiya 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 8 Atishbaz, Darugar 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 9 Bairagi 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 10 Banjara, Mukeri, Rankia, Mekrani 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 Barhai, Badhai, Viswakarma, 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 11 Ramgarhia 12 Bari (Those who are not SCs) 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 13 Bind 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 14 Biyar 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 15 Bhand 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 16 Bhar 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 17 Bhathiara 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 Bhurji, Bharbhuja, Bharbhunja, Bhooj, 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt.08/12/2011 18 Kandu Bot (does not include “Bhotia” who are 12015/13/2010-B.C.II.