Michael Sandle Archive Exhibition Article 3, Inferno Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stones of London's War Memorials

Urban Geology in London No. 23 The Stones of London’s War Memorials ‘If I should die, think only this of me; That there’s some corner of a foreign field That is forever England’ The Soldier, Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) Memorial at the Tower of London for the centenary of the outbreak of WWI: 'Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red' by ceramicist Paul Cummins. The opening lines of Rupert Brooke’s famous poem (above) illustrates muCh of the sentiments assoCiated with the design of war memorials and war graves. It has beCome traditional, on the most part, for stones representing the soldiers’ Countries of origin to be used in memorials ConstruCted to Commemorate them. For example, the war memorials commemorating the British Forces killed during WWI in FranCe and Belgium, such as Thiepval and the Menin Gate, are built from briCk, with piers, vaults, Columns and the panels bearing the insCriptions of names in Portland Stone. As we will see below, stones have been imported from all over the World to Commemorate the soldiers from those Countries who fought in the European theatres of the first half of the 20th Century. Indeed there are Corners of foreign fields, or in faCt London, that are forever Australian, Canadian or Maltese. Many of the War Memorials and their stones Catalogued below have been previously desCribed in other Urban Geology in London Guides. These inClude the memorials in the viCinity of Hyde Park Corner (Siddall & Clements, 2013), on the ViCtoria Embankment (Siddall & Clements, 2014) and the Malta Memorial near the Tower of London (Siddall, 2014). -

A Demographic and Socio-Economie Profile of Ageing in Malta %Eno

A Demographic and Socio-Economie Profile of Ageing in Malta %eno CamiCCeri CICRED INIA Paris Valletta FRANCE MALTA A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile of Ageing in Malta A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile of Ageing in Malta %g.no CamiCCeri Reno Camilleri Ministry for Economic Services Auberge d'Aragon, Valletta Published by the International Institute on Ageing (United Nations - Malta) © INIAICICRED 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Reno Camilleri A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile of Ageing in Malta ISBN 92-9103-024-4 Set by the International Institute on Ageing (United Nations — Malta) Design and Typesetting: Josanne Altard Printed in Malta by Union Print Co. Ltd., Valletta, MALTA Foreword The present series of country monographs on "the demographic and socio-economic aspects of population ageing" is the result of a long collaborative effort initiated in 1982 by the Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography (CICRED). The programme was generously supported by the United Nations Population Fund and various national institutions, in particular the "Université de Montréal", Canada and Duke University, U.S.A. Moreover, the realisation of this project has been facilitated through its co-sponsorship with the International Institute on Ageing (United Nations - Malta), popularly known as INIA/ There is no doubt that these country monographs will be useful to a large range of scholars and decision-makers in many places of the world. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units in World War 2 and Missing with No Known Grave

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2. -

Bridgwater 1914-18 Adams James Stoker Petty

Bridgwater 1914-18 Adams James Stoker Petty Officer 309198 H.M.S “Valkyrie” Royal Navy. Killed by an explosion 22nd December 1917. James Adams was the 34 year old husband of Eliza Emma Duckham (formerly Adams of 4, Halesleigh Road, Bridgwater. Born at Huntworth. Bridgwater (Wembdon Road) Cemetery Church portion Location IV. 8. 3. Adams Albert James Corporal 266852 1st/6th Battalion TF Devonshire Regiment. Died 9th February 1919. Husband of Annie Adams, of Langley Marsh, Wiveliscombe, Somereset. Bridgwater (St Johns) Cemetery. Ref 2 2572. Allen Sidney Private 7312 19th (County of London) Battalion (St Pancras) The London Regiment (141st Infantry Brigade 47th (2nd London) Territorial Division). (formerly 3049 Somerset Light Infantry). Killed in action 14th November 1916. Sydney Allen was the 29 year old son of William Charles and Emily Allen, of Pathfinder Terrace, Bridgwater. Chester Farm Cemetery, Zillebeke, West Flanders, Belgium. Plot 1. Row J Grave 9. Andrews Willaim Private 1014 West Somerset Yeomanry. Died in Malta 19th November 1915. He was the son of Walter and Mary Ann Andrews, of Stringston, Holford, Bridgwater. Pieta Military Cemetery, Malta. Plot D. Row VII. Grave 3. Anglin Denis Patrick Private 3/6773 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. (11th Infantry Brigade 4th Division). Killed in action during the attack on and around the “Quadrilateral” a heavily fortified system of enemy trenches on Redan Ridge near the village of Serre 1st July 1916 the first day of the 1916 Battle of the Somme. He has no known grave, being commemorated n the Thiepval Memorial to the ‘Missing’ of the Somme. Anglin Joseph A/Sergeant 9566 Mentioned in Despatches 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units in World War 2 and Missing with No Known Grave

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2. -

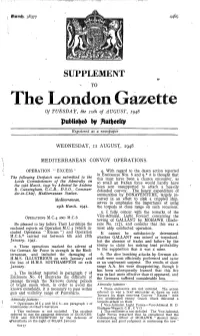

SUPPLEMENT -TO the of TUESDAY, the Loth of AUGUST, 1948

ffhimb, 38377 4469 SUPPLEMENT -TO The Of TUESDAY, the loth of AUGUST, 1948 Registered as a newspaper WEDNESDAY, n AUGUST, 1948 MEDITERRANEAN CONVOY OPERATIONS. OPERATION " EXCESS " 4. With regard to the dawn action reported in Enclosures Nos. 6 and 9,* it is thought that The following Despatch was submitted to the this must have been a chance encounter, as Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on so small an Italian force would hardly have the igth March, 1941 by Admiral Sir Andrew been sent unsupported to attack a heavily B. Cunningham, G.C.B., D.S.O., Comman- defended convoy. The heavy expenditure of der-in-Chi'ef, Mediterranean Station. ammunition by BON A VENTURE, largely in- Mediterranean, curred in an effort to sink a crippled ship, serves to emphasise the importance of using iqth March, 1941. the torpedo at close range on such occasions. 5. I fully concur with the remarks of the OPERATIONS M.C.4 AND M.C.6 Vice-Admiral, Light Forcesf concerning the towing of GALLANT by MOHAWK (Enclo- Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships the sure No. i if), and consider that this was a enclosed reports on Operation M.C 4 (which in- most ably conducted operation. cluded Operation " Excess ") and Operation It cannot be satisfactorily determined M.C.6,* carried out between 6th and i8th whether GALLANT was mined or torpedoed, January, 1941. but the absence of tracks and failure by the 2. These operations marked the advent of enemy to claim her sinking lend probability the German Air Force in strength in the Medi- to the supposition that it was a mine. -

MMMMMM MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 281 August 2019

1 MMMMMM MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 281 August 2019 1 2 MMMMMM MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 281 August 2019 Operation Pedestal – Santa marija convoy Operation Pedestal (referenced in Italian sources as the Battaglia di Mezzo Agosto) was a British operation to get desperately needed supplies to the island of Malta in August 1942, during the Second World War. Malta was the base from which surface ships, submarines and aircraft attacked Axis convoys carrying supplies to the Italian and German armies in North Africa. From 1940 to 1942, Malta was under siege, blockaded by Axis air and naval forces. To sustain Malta, the United Kingdom had to get convoys through at all costs. Despite serious losses, just enough supplies were delivered for Malta to continue resistance, although it ceased to be an effective offensive base for much of 1942. The most crucial supply was fuel delivered by the SS Ohio, an American-built tanker with a British crew. The operation officially started on 3 August 1942 and the convoy sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar on the night of 9/10 August. The convoy is also known as the Battle of Mid-August in Italy and as the Konvoj ta' Santa Marija in Malta; the arrival of the last ships of the convoy on 15 August 1942, coincided with the Feast of the Assumption (Santa Marija). The name Santa Marija Convoy or Sta Marija Convoy is still used and the day's public holiday and celebrations, in part, honour the arrival of the convoy. The attempt to run fifty ships past bombers, E-boats, minefields and submarines has gone down in military history as one of the most important British strategic victories of the Second World War. -

MB1/R Mountbatten Papers: Papers of Edwina, Countess Mountbatten of Burma, 1948-60

1 MB1/R Mountbatten Papers: Papers of Edwina, Countess Mountbatten of Burma, 1948-60 MB1/R3 Accounts, 1954-5 MB1/R4 Jitendra Arya, photographer 1951-9 MB1/R5 Requests for Countess Mountbatten’s autograph 1948-60 MB1/R6 Miscellaneous correspondents: A 1951 MB1/R7 Miscellaneous correspondents: A-E 1948-9 MB1/R8 Miscellaneous correspondents: A-Ag 1952-9 MB1/R9 Miscellaneous correspondents: Ag-Am 1952-9 MB1/R10 Miscellaneous correspondents: An-Az 1927-58 MB1/R11 Shri S.L.Bahl 1953-9 MB1/R12 William Maxwell Aitken, first Baron Beaverbrook 1940-4 MB1/R13 Requests for financial assistance 1948-51 MB1/R14 Belgrave Mews North, mainly concerning building and maintenance work 1950-5 MB1/R15 Percy Bidwell, CPO writer: mainly concerning the Royal Naval Benevolent Trust 1953-60 MB1/R16 Georgina Blois: financial matters, deeds of covenant 1955-60 MB1/R20 International exhibition, Brussels 1958 MB1/R21 Invitations to Buckingham Palace, funeral of George VI 1952-6 MB1/R22 Burgot Rentals Limited 1951-2 MB1/R23 Mary Burrell 1952 MB1/R24 Miscellaneous correspondents: Ba-Bo 1942-52 MB1/R25 Miscellaneous correspondents: Ba 1951-60 MB1/R26 Miscellaneous correspondents: Be-Bl 1953-60 MB1/R27 Miscellaneous correspondents: Be-Bl 1952-60 MB1/R28 Miscellaneous correspondents: Bo; black and white photographs 1952-9 MB1/R29 Miscellaneous correspondents: Br 1953-60 MB1/R30 Miscellaneous correspondents: Br-Bu 1942-52 MB1/R31 Miscellaneous correspondents: Br 1950-60 MB1/R32 Miscellaneous correspondents: Bu 1953-9 MB1/R33 Miscellaneous correspondents: Bu 1953-9 2 MB1/R34 -

List of Trinity Men Who Fell in World War II

TRINITY COLLEGE WAR MEMORIAL MCMXXXIX-MCMXLV PRO MURO ERANT NOBIS TAM IN NOCTE QUAM IN DIE They were a wall unto us both by night and day. 1 Samuel 25: 16 Abel-Smith, Robert Eustace Anderson, Ian Francis Born March 24 1909 at Cadogan Square, London SW1, son Born Feb 25 1917 in Wokingham, Berks. Son of Lt-Colonel of Eustace Abel Smith JP. School: Eton. Admitted as Francis Anderson DSO MC. School: Eton. Admitted as Pensioner at Trinity Oct 1 1927; BA 1930. Captain, 3rd Pensioner at Trinity Oct 1 1935; BA 1938. Pilot Officer, RAF Grenadier Guards. Died May 21 1940. Buried in Esquelmes No 53 Squadron. Died April 9 1941. Buried in Wokingham War Cemetery, Hainaut, Belgium. FWR, CWGC (All Saints) Churchyard. FWR, CWGC Ades, Edmund Henry [Edmond] Anderson, John Thomson McKellar Born July 24 1918 in Alexandria, Egypt. Son of Elie Ades and ‘Jock’ Anderson was born Jan 12 1918 in Hampstead, London, the The Hon. Mrs Rose O’Brien. School: Charterhouse. son of John McNicol McKellar Anderson. School: Stowe. Admitted as Pensioner at Trinity Oct 1 1936; BA 1939. Admitted as Pensioner at Trinity Oct 1 1936; BA 1939. Lieutenant, 2nd Royal Gloucestershire Hussars, Royal Married to Moira Anderson of Chessington, Surrey. Major, Armoured Corps. Died May 27 1942. Buried in 8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Victoria Cross, DSO. Knightsbridge War Cemetery, Libya. FWR, CWGC ‘During the attack on Longstop Hill, Tunisia, on 23rd April, 1943 Major Anderson, as leading Company Commander, led Aguirre, Enrique Manuel the assault on the battalion’s first objective. Very heavy Born May 25 1903 in Anerley, Middlesex. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 359 February 2021 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 359 February 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 359 February 2021 How Pembroke’s once- popular entertainment venue Australia Hall turned into a sad ruin The 105-year-old building was buzzing with life in the first half of the 20th century Caroline Curmi If you’ve ever taken a stroll through Pembroke, you might have spotted a once majestic (but now a roofless and decaying) building within the parameters of the town. Built between 1915 and 1916 by the Australian branch of the British Red Cross Services, it was aptly christened as Australia Hall. Its original purpose had been to entertain wounded soldiers from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps recuperating in Malta during WWI. Large and spacious, it could fit 2,000 people in its massive hall (which would sometimes double as a theatre) and even had its own library. Later, it was passed on to a section of the British government in charge of overseeing recreational space for its troops, with the hall being subsequently fitted with a projector and transformed into a cinema in 1921. It would serve as an entertainment hall right till the last days of the British retreat from Malta. After the islands’ independence, the property passed on to the Maltese government and later to third parties, but it was never put back in operation. In 1996, Australia Hall was listed as a Grade 2 National Monument but by December 1998, it suffered a catastrophic fire that destroyed its roof. Although it was believed to have been caused by an arsonist, the case was never solved, and repairs were never effected. -

Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal A Thumbnail View In 1942, Britain was waging war in the Mediterranean against the Germans and Italians in North Africa and Malta-a British military base from where British aircraft, submarines and cruisers were able to wreak havoc upon the Axis convoys. In December 1941 the Germans decided to neutralize Malta by means of a blockade and aerial bombardment.. Malta's strategic location was key to holding the Mediterranean, but food and oil had to get through past the Axis bombers and submarines. The 250,000 Maltese and 20,000 British defenders were dependent on imported food and oil. Convoys were not successful in getting thru and small amounts of food and oil was being brought in by submarine and fast minesweepers. During the six month period from February to July 1942, only five supply ships had manage to get through and three of these were promptly sunk upon their arrival by the Luftwaffe, with the loss of virtually all their cargoes. Due to the lack of food, the island faced starvation and a surrender date in September, 1942 had already been established. A decision was made in London to get a convoy through to Malta, no matter what the cost. This convoy would include one precious tanker. If all the cargo ships reached Malta but the tanker was lost, the effort would be militarily wasted since Malta's aircraft and naval ships would be useless. The convoy was code-named 'Operation Pedestal' and was scheduled for the first two weeks of August, 1942, in order to take advantage of moonless nights. -

Malta: Health System Review

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 16 No. 1 2014 Malta Health system review Natasha Azzopardi Muscat • Neville Calleja Antoinette Calleja • Jonathan Cylus Jonathan Cylus (Editor), Sarah Thomson and Ewout van Ginneken were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom Elias Mossialos, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom Sarah Thomson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Ewout van Ginneken, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Series coordinator Gabriele Pastorino, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Editorial team Jonathan Cylus, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Cristina Hernández-Quevedo, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Marina Karanikolos, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Maresso, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies David McDaid, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sherry Merkur, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Philipa Mladovsky, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Dimitra Panteli, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Wilm Quentin, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Erica Richardson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Sagan, European Observatory