Gatekeepers” Come Under Prosecutors’ Scrutiny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Award Ceremony November 6, 2013 WELCOME NOTE from RICHARD M

AWARD CEREMONY NOVEMBER 6, 2013 WELCOME NOTE from RICHARD M. ABORN Dear Friends, Welcome to the third annual fundraiser for the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City. This year we celebrate 35 years of effective advocacy – work which has made our city BOARD of DIRECTORS safer and influenced the direction of national, state, and local criminal justice policy. At the Crime Commission, we are prouder than ever of the role we play in the public process. We are also grateful for the generous support of people like you, who make our work possible. CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN Richard J. Ciecka Gary A. Beller Keeping citizens safe and government responsive requires vigilant research and analysis Mutual of America (Retired) MetLife (Retired) in order to develop smart ideas for improving law enforcement and our criminal justice system. To enable positive change, we are continually looking for new trends in crime and Thomas A. Dunne Lauren Resnick public safety management while staying at the forefront of core issue areas such as guns, Fordham University Baker Hostetler gangs, cyber crime, juvenile justice, policing, and terrorism. Abby Fiorella Lewis Rice This year has been as busy as ever. We’ve stoked important policy discussions, added to MasterCard Worldwide Estée Lauder Companies critical debates, and offered useful ideas for reform. From hosting influential voices in public safety – such as Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman Richard Girgenti J. Brendan Ryan and United States Attorney Preet Bharara – at our Speaker Series forums, to developing KPMG LLP DraftFCB cyber crime education initiatives and insightful research on the city’s gangs, the Crime Commission continued its tradition as the pre-eminent advocate for a safer New York. -

Lessons from New York's Recent Experience with Capital Punishment

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU ASK FOR: LESSONS FROM NEW YORK’S RECENT EXPERIENCE WITH CAPITAL PUNISHMENT James R. Acker* INTRODUCTION On March 7, 1995, Governor George Pataki signed legislation authorizing the death penalty in New York for first-degree murder,1 representing the State’s first capital punishment law enacted in the post- Furman era.2 By taking this action the governor made good on a pledge that was central to his campaign to unseat Mario Cuomo, a three-term incumbent who, like his predecessor, Hugh Carey, had repeatedly vetoed legislative efforts to resuscitate New York’s death penalty after it had been declared unconstitutional.3 The promised law was greeted with enthusiasm. The audience at the new governor’s inauguration reserved its most spirited 4 ovation for Pataki’s reaffirmation of his support for capital punishment. * Distinguished Teaching Professor, School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany; Ph.D. 1987, University at Albany; J.D. 1976, Duke Law School; B.A. 1972, Indiana University. In the spirit of full disclosure, the author appeared as a witness at one of the public hearings (Jan. 25, 2005) sponsored by the Assembly Committees discussed in this Article. 1. Twelve categories of first-degree murder were made punishable by death under the 1995 legislation, and a thirteenth type (killing in furtherance of an act of terrorism) was added following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. N.Y. PENAL LAW § 125.27 (McKinney 2003). Also detailed were the procedures governing the prosecution’s filing of a notice of intent to seek the death penalty, N.Y. -

Dia Report FINAL.Indd

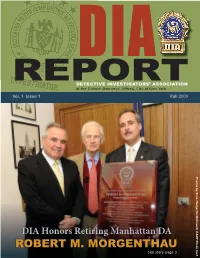

DIA REPORTDETECTIVE INVESTIGATORS’ ASSOCIATION of the District Attorneys’ Offi ces, City of New York Vol. 1 Issue 1 Fall 2009 Photos by Rosa Margarita McDowell, DANY Photo Unit DIA Honors Retiring Manhattan DA ROBERT M. MORGENTHAU See story page 3 PRESIDENTS MESSAGE JOHN FLEMING DETECTIVE INVESTIGATORS’ Welcome ASSOCIATION to the Detective larger Investigators’ organizations, DISTRICT ATTORNEYS’ Association we will have a stronger voice OFFICES – CITY OF NEW YORK, INC. newly revised to get things done. newsletter. Every union is a continuous work in PO Box 130405 Keeping New York, NY 10013 with our progress. Members come and go, but 646.533.1341 commitment those unions that prosper are the 800.88.DEA.88 to providing ones that constantly stand up for the our members with a level of membership. Our progress can be www.nycdia.com professionalism and honesty, we have traced in no small part to an increased restarted our newsletter that ceased confi dence in the union by the member. JOHN M. FLEMING many years back. Our goal is to insure It is your trust that allows us to grow. President Your Trustees play a large part in this that you are well informed and kept ANTHONY P. FRANZOLIN abreast of what is going on in all the endeavor and I urge you to keep them Vice President boroughs. If you have any suggestions abreast of all that is going on in your about what you’d like to see included, command. JACK FRECK Secretary-Treasurer or have information you would like The newsletter, like our web site, will to send in for inclusion, please let us be another tool the union can use to Board of Trustees know. -

Heritage Vol.1 No.2 Newsletter of the American Jewish Historical Society Fall/Winter 2003

HERITAGE VOL.1 NO.2 NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY FALL/WINTER 2003 “As Seen By…” Great Jewish- American Photographers TIME LIFE PICTURES © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INC. Baseball’s First Jewish Superstar Archival Treasure Trove Yiddish Theater in America American Jewish Historical Society 2002 -2003 Gift Roster This list reflects donations through April 2003. We extend our thanks to the many hundreds of other wonderful donors whose names do not appear here. Over $200,000 Genevieve & Justin L. Wyner $100,000 + Ann E. & Kenneth J. Bialkin Marion & George Blumenthal Ruth & Sidney Lapidus Barbara & Ira A. Lipman $25,000 + Citigroup Foundation Mr. David S. Gottesman Yvonne S. & Leslie M. Pollack Dianne B. and David J. Stern The Horace W. Goldsmith Linda & Michael Jesselson Nancy F. & David P. Solomon Mr. and Mrs. Sanford I. Weill Foundation Sandra C. & Kenneth D. Malamed Diane & Joseph S. Steinberg $10,000 + Mr. S. Daniel Abraham Edith & Henry J. Everett Mr. Jean-Marie Messier Muriel K. and David R Pokross Mr. Donald L. SaundersDr. and Elsie & M. Bernard Aidinoff Stephen and Myrna Greenberg Mr. Thomas Moran Mrs. Nancy T. Polevoy Mrs. Herbert Schilder Mr. Ted Benard-Cutler Mrs. Erica Jesselson Ruth G. & Edgar J. Nathan, III Mr. Joel Press Francesca & Bruce Slovin Mr. Len Blavatnik Renee & Daniel R. Kaplan National Basketball Association Mr. and Mrs. James Ratner Mr. Stanley Snider Mr. Edgar Bronfman Mr. and Mrs. Norman B. Leventhal National Hockey League Foundation Patrick and Chris Riley aMrs. Louise B. Stern Mr. Stanley Cohen Mr. Leonard Litwin Mr. George Noble Ambassador and Mrs. Felix Rohatyn Mr. -

The Common Law Powers of the New York State Attorney General

THE COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL Bennett Liebman* The role of the Attorney General in New York State has become increasingly active, shifting from mostly defensive representation of New York to also encompass affirmative litigation on behalf of the state and its citizens. As newly-active state Attorneys General across the country begin to play a larger role in national politics and policymaking, the scope of the powers of the Attorney General in New York State has never been more important. This Article traces the constitutional and historical development of the At- torney General in New York State, arguing that the office retains a signifi- cant body of common law powers, many of which are underutilized. The Article concludes with a discussion of how these powers might influence the actions of the Attorney General in New York State in the future. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 96 I. HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ................................ 97 A. The Advent of Affirmative Lawsuits ............. 97 B. Constitutional History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 100 C. Statutory History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 106 II. COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL . 117 A. Historic Common Law Powers of the Attorney General ......................................... 117 B. The Tweed Ring and the Attorney General ....... 122 C. Common Law Prosecutorial Powers of the Attorney General ................................ 126 D. Non-Criminal Common Law Powers ............. 136 * Bennett Liebman is a Government Lawyer in Residence at Albany Law School. At Albany Law School, he has served variously as the Executive Director, the Acting Director and the Interim Director of the Government Law Center. -

Manhattan DA Announces New Unit to Investigate Public Corruption

1 More SEARCH Saturday, October 23, 2010 As of 9:18 PM EDT As of New York 64º | 56º U.S. Edition Home Today's Paper Video Blogs Journal Community Log In World U.S. New York Business Markets Tech Personal Finance Life & Culture Opinion Careers Real Estate Small Business WSJ BLOGS High Tide: From A Vatican Nigeria Files Corruption Appeal To An Ally To Ukraine Charges Against German Corruption Currents Ex-Premier Companies Commentary and news about money laundering, bribery, terrorism finance and sanctions. OCTOBER 20, 2010, 3:54 PM ET Manhattan DA Announces New Unit To Investigate Public Corruption Article Comments CORRUPTION CURRENTS HOME PAGE » Email Print Permalink Like 1 + More Text By Samuel Rubenfeld Updated Below Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. announced the formation of a Public Integrity unit devoted to investigating public corruption, including cases of bribery, malfeasance, election fraud and ethics violations. The new unit is part of an overhaul of the office’s Rackets Bureau, which was created in January 1938 and has been responsible for the prosecution of some of New York’s most notorious organized crime cases and high-profile corruption cases, including a scheme in 2004 in which contractors About Corruption Currents Follow Us: bribed Metropolitan Transit Authority officials in Corruption Currents, The Wall Street Journal’s corruption blog, will dig into the ever-present and ever-changing world of corporate exchange for millions of Brendan McDermid/Reuters corruption. It will be a source of news, analysis and commentary dollars in contracts. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. (C) speaks as Manhattan for those who earn a living by finding corruption or by avoiding it. -

Columbia Law School Winter 2010

From the Dean On August 17, 2009, Dean David M. Schizer offered his welcoming remarks to the incoming class of J.D. and LL.M. students at Columbia Law School. An edited version of that address appears below. This is both an inspiring and a challenging time to come that excellence is measured in many different ways—in to law school. It is inspiring because the world needs you the pride you take in your work, in the reputation you more than ever. We live in troubled times, and many of develop among your peers, and, more importantly, in the great issues of our day are inextricably tied to law. Our the eyes of the people you have helped. But to my mind, financial system has foundered, and we need to respond excellence should not be measured in dollars. with more effective corporate governance and wiser The second fundamental truth to remember is that regulation. Innovation, competition, and free trade need integrity is the bedrock of any successful career. It is a to be encouraged in order for our economy to flourish. great source of satisfaction to know that you have earned Because of the significant demands on our public sector, your successes, that you didn’t cut any corners, and that our tax system needs to collect revenue efficiently and people trust you. fairly. Our dependence on imported fuel jeopardizes our As for the specifics of what career choices to make, national security, and our emission of greenhouse gases you are just beginning that journey. Most likely, there places our environment at risk. -

Freedoms Parkllc

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT F0 UR FREEDOMS HONORARY COMMITTEE Chairs PARKLLC Jimmy Carter George H.W. Bush William J. Clinton WILLIAM J. VANDEN HEUVEL Mrs. Ronald Reagan July 18,2012 ACTION rr-- CHAIRMAN Co-Chairs Tom Brokaw COpy Hugh L.Carey Anne Cox Chambers Henry Cisneros H.E. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Mario Cuomo Margaret Truman Daniel· Secretary-General of the United Nations Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel New York, NY 10017 David N. Dinkins Robin Chandler Duke DavidEisenhower Dear Mr. Secretary-General: Julie Nixon Eisenhower Frederick P. Furth Rudolph Giuliani ~h,i~h_Isl!~i! L~jli 9P~I.1 Doris Keams Goodwin The Franklin D RooseveltFourFreedoms Park, to Agnes Gund !l1S?publi~ onRooseveltIsland ion Q~tQP~r ofthisyear, Perhaps you have Dolores Huerta caught a glimpse of the Louis Kahn designed memorial to President Roosevelt Lady Bird Johnson' Vernon E.Jordan, Jr. from your office during 28 months of construction. Caroline Kennedy Henry Kissinger Edward I.Koch We hope to celebrate the profound connection between President Franklin William E.Leuchtenburg Roosevelt' the United Nations importantpart'of opening H. Carl McCall and 'asan this '-..' William J. McDonough extr'!QI~!!l~~ ~e~· ~Lyl~~~Qice.- We-wntet~iiSk -.(o r~~ri~f !p~~~~_~g~ iVi!~~¥~~ to Donald F.McHenry present a proposal for United Nations Day at the Franklin RooseveltFour George J. Mitchell D. Robert Morgenthau Freedoms Park. Perhaps we could meet on /~:~gus~ ,J_,~ )~ .~~ -~ ~- Your - --- ,~ Sam Nunn p~j_~jp~tiQI1 _ .~Q_!1ld @ ~y-en1. Peter G.Peterson mark this as histQr!c Colin L.Powell Bernard Rapoport , @~~! . Anna Eleanor Roosevelt You would be our most honored Others would include the United Arthur Ross" Nations Permanent Representatives, leaders of the UN community and senior George P.Shultz UNA UN would Robert S.Strauss officials ofthe Secretariat. -

1 Forty-Fourth Street Notes

Forty-Fourth Street Notes Highlights: THE TRUE HEROES March 2007 By Barry Kamins, President The Trial of Saddam he name of Charles “Cully” Stimson has begun to ters and suggested that companies should reconsider fade into history and will be a footnote in the doing business with them. In response, we wrote to Hussein: A Retrospective: Tnot-too-distant future. As you may remember, members of Congress to urge the Armed Services March 6, Page 5 Mr. Stimson was the administration’s point person for Committee to conduct hearings on the efforts of the detainee policy for the last year as deputy assistant sec- Executive Branch, including those of Mr. Stimson, to Professional Development: retary for detainee affairs. He gained substantial noto- harass and intimidate attorneys providing this repre- Acting Ethically – riety on January 11th when, during an interview with a sentation and to interfere with the attorney-client Incorporating Professional local Washington-based station, he expressed dismay relationship. Responsibility into that attorneys at many of the nation’s top law firms Faced with an avalanche of criticism, Stimson offered Professional Development: were representing prisoners at an “apology” six days later, and resigned on February March 8, Page 6 Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and 2nd. However, in his statement, he still did not accept that the firms’ corporate clients any responsibility for trying to drive a wedge between should consider ending their The Annual Justice attorneys representing the detainees and the firms’ business ties with those firms. corporate clients. As a senior public official who sets Ruth Bader Ginsburg While an almost universal criti- Distinguished Lecture on policy on the detainees, and as an attorney, Stimson’s cal response silenced his remarks are unprofessional and possibly unethical, in Women and the Law: remarks, unfortunately the poli- that they are prejudicial to the administration of jus- March 13, Page 7 cies of the administration with tice. -

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS in AMERICAN POLITICS Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections

This item is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 This product is no longer affiliated or otherwise associated with any LexisNexis® company. Please contact ProQuest® with any questions or comments related to this product. About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world’s knowledge – from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway ■ P.O Box 1346 ■ Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ■ USA ■ Tel: 734.461.4700 ■ Toll-free 800-521-0600 ■ www.proquest.com A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections MorgenthauThe Diaries World War II and Postwar Planning, 1943–1945 A UPA Collection from Cover: Henry Morgenthau, Jr., inscribed this photo to President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a souvenir of the defense bond campaign opening in 1941, well before Pearl Harbor. His diaries show how early and often Morgenthau was concerned about the inflationary pressures of rearmament. Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, National Archives and Records Administration. RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microforms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William Leuchtenberg THE MORGENTHAU DIARIES World War II and Postwar Planning, 1943–1945 Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Robert E. -

Nieves, Et Al. V. Thomas, Et Al. 02-CV-09744-U.S. District Court Civil Docket

US District Court Civil Docket as of 02/24/2004 Retrieved from the court on Wednesday, August 24, 2005 U.S. District Court Southern District of New York (Foley Square) CIVIL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 1:02-cv-09744-RMB-KNF Nieves v. Thomas, et al Date Filed: 12/10/2002 Assigned to: Judge Richard M. Berman Jury Demand: None Referred to: Magistrate Judge Kevin Nathaniel Fox Nature of Suit: 530 Habeas Corpus Demand: $0 (General) Cause: 28:2241 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus (federa Jurisdiction: Federal Question Petitioner Carlos Nieves represented by Carlos Nieves 95-A-5487 900 King Highway Warwick, NY 10990 PRO SE V. Respondent Gail Thomas Acting Superintendent, Mid-Orange Correctional Facility Respondent Brion Travis Chairman, New York Date Filed # Docket Text 12/10/2002 1 PETITION for writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 USC 2241. (gf) (Entered: 12/11/2002) 12/10/2002 2 MEMORANDUM OF LAW by Carlos Nieves in support of [1-1] petition . (gf) (Entered: 12/11/2002) 12/10/2002 3 NOTICE OF MOTION by Carlos Nieves to grant bailto habeas corpus . Return Date not indicated. (gf) (Entered: 12/11/2002) 12/10/2002 4 NOTICE OF MOTION by Carlos Nieves purs. to Rule 6 of the Rules governing 2254 of the U.S.C. for leave to conduct discovery , and for the Court to request counsel . Return Date not indicated. (gf) (Entered: 12/11/2002) 12/10/2002 Magistrate Judge Kevin N. Fox is so designated. (gf) (Entered: 12/11/2002) 12/18/2002 5 Order that case be referred to the Clerk of Court for assignment to a Magistrate Judge for General Pretrial/Including Initial Case Management Conference. -

The Insurance Policy Enforcement Journal Is the Industry’S Premiere Source for Information and Analysis of the Enforcement of Insurance Policy Provisions

Volume 7 | issue 1 EThe Insurancenf Policyo Enforcementrce Journal IN THIS ISSUE Gene COVER STORY Celebrating the incredible journey Anderson of Gene Anderson, from humble THE DEAN OF beginnings on a farm to slaying POLICYHOLDERS’ corporate giants. (And spinning AttORNEYS some great stories along the way.) LOOKS BACK ADDICTED TO AIG? The impacts of the troubles for AIG are profound for business and policyholders. Special report begins on Page 9. A MERGER OF COASTS AND CULTURE Meet the key people at Anderson Kill Wood & Bender, LLP. Enforce: The Insurance Policy Enforcement Journal is the industry’s premiere source for information and analysis of the enforcement of insurance policy provisions. Settle for Everything.® Enforce Contents 9 Special Report: The AIG Addiction The impact of the crippled giant on the insurance marketplace. What happens to policyholders if AIG enters bankruptcy? Page 10 A respected broker describes how brokers can help during a time of turmoil in the insurance industry. Page 15 Would Americans be better served if the federal government regulated the insurance industry? Page 17 22 When East Meets West The merger of Anderson Kill & Olick, P.C. and Wood & Bender, LLP is about more than two firms in the same practice area. They share a culture of community service. Meet the key attorneys at Anderson Kill Wood & Bender, LLP. 25 Keeping an Eye on the Ball By John G. Nevius, P.E., Edward J. Stein, and David E. Wood Hot button issues to watch: Environmental Liability; General vs. Professional Services Liability; Directors’ and Officers’ Liability. 30 Attorney Conflicts of Interest By William G.