Written Evidence Submitted by National Association of Aonbs (TPW0069)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nidderdale AONB SCHEDULE 2 PART 1 - STAFF UNIT STRUCTURE

THIS MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT is made the 13 day of December 2011 BETWEEN (1) Defra, Temple Quay House, 2 The Square, Temple Quay, Bristol BS1 6NB (2) Harrogate Borough Council (“Host Authority”). (3) North Yorkshire County Council “the Parties” IT IS AGREED as follows: WHEREAS (A) This Agreement provides a framework for the delivery of duties and obligations arising from Part IV of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 including the operation and management of an AONB Partnership (“the Partnership”), a Staff Unit to act on behalf of the Partnership and the publishing, reviewing and monitoring of the Management Plan. (B) This Agreement also sets out a shared vision for and commitment to AONB management by all Parties to the Agreement. It outlines the expectations on all Parties to achieve this vision, including a local reflection of the national tri-partite agreement between Defra, Natural England and the National Association for Areas for Outstanding Natural Beauty (“NAAONB”) (C) This Agreement is intended to bind partners to give medium term security, matching Defra’s commitment to a AONB funding programme over a 4 year CSR period. NOW IT IS AGREED as follows 1. Definitions and Interpretation 1.1 In this Agreement the following words and expressions shall have the following meanings unless the context requires otherwise: “AONB” means an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty “the Partnership” means AONB Partnership comprising of the organisations listed in Schedule 1 “Funding Partners” means the following Local Authority Funding Partners -

Moorlands: People, Places, Stories Exploring People’S Experiences of the Upper Nidderdale Moorland Through Time

Moorlands: People, Places, Stories Exploring people’s experiences of the Upper Nidderdale moorland through time What do the moorlands mean to you? (from top left: S Wilson, I Whittaker, A Sijpesteijn, Nidderdale AONB, H Jones, I Whittaker; centre: D Powell, Adrian Bury Associates) Sharing stories – listening to the past Everyone, young and old, has a story to tell; unique memories and experiences that would otherwise be lost over time. These personal accounts reveal much about the history of the moorlands, a personal history that is not written down. Here we have an opportunity to preserve our moorland heritage by capturing aspects of history and experiences that would otherwise be lost, and to look at the landscape through different eyes. Guidance Sheet A (V1) Why the moorlands? The moorlands have been influenced by humans over thousands of years, with successive generations finding different ways to exploit the area’s rich resources, leaving their mark as clues for future generations. We hope that the project will help capture the character of the moorland landscape and of the people that live, work, and enjoy them. Join the team Moorlands: People, Places, Stories will be delivered by a newly formed volunteer group. Training will be provided and the team will be supported by Louise Brown (Historic Nidderdale Project Officer), oral history consultant Dr Robert Light, and landscape archaeologist Dr Jonathan Finch from the University of York. It is hoped that documents and photographs shared by interviewees might spark interest in carrying out some additional research. There will be the opportunity for those that are interested to become affiliated to the University of York in order to access online resources, as well as being able to access the archives held by Nidderdale Museum and at North Yorkshire County Council. -

Draft LGAP Your Dales Rocks Project

i ii The ‘Your Dales Rocks Project’ – A Draft Local Geodiversity Action Plan (2006-2011) for the Yorkshire Dales and the Craven Lowlands The Yorkshire Dales and Craven Lowlands have a diverse landscape that reflects the underlying geology and its history. The auditing and protection of this geodiversity is important to help preserve the landscape and the underlying geology. It is also important to help integrate the needs of the local population, education, recreation and science with quarrying and the National need for aggregate. This draft Action Plan sets out a framework of actions for auditing, recording and monitoring the geodiversity of the Dales and Craven lowlands. As its title indicates, it is a draft and subject to change as comments are made and incorporated. The implementation of the Action Plan is also dependent on funding becoming available. For this draft, the North Yorkshire Geodiversity Partnership is particularly thankful for the support of the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund from the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, administered by English Nature, and the Landscape, Access and Recreation side of the Countryside Agency. It is also very grateful to the organisations of the authors and steering group listed below (and whose logos appear on the front cover) that have invested staff time and money to make this draft Action Plan a reality. Over time, the plan will evolve and Adrian Kidd, the project officer (address below) welcomes suggestions and comments, which will help to formulate the final -

CRAB HOUSE Healey, Ripon CRAB HOUSE HEALEY, RIPON, NORTH YORKSHIRE, HG4 4LP

CRAB HOUSE Healey, Ripon CRAB HOUSE HEALEY, RIPON, NORTH YORKSHIRE, HG4 4LP Northallerton Station 33 miles • Healey 1 mile • Masham 4 miles • Ripon 13 miles BEAUTIFULLY LOCATED RENOVATION OPPORTUNITY OF A TRADITIONAL FARMHOUSE AND BUILDINGS. Accommodation Stone-built farmhouse with a range of traditional and more modern buildings. Current accommodation includes: Three reception rooms • kitchen five bedrooms • bathroom and shower room • About 2,400 sqft. Large garden area • Paddock Approximately 3 acres in all Further land may be available by separate negotiation 15 High Street, Leyburn, DL8 5AH. Tel: 01969 600120 www.gscgrays.co.uk [email protected] Offices also at: Alnwick Chester-le-Street Colburn Easingwold Tel: 01665 568310 Tel: 0191 303 9540 Tel: 01748 897610 Tel: 01347 837100 Hamsterley Lambton Estate Leyburn Stokesley Tel: 01388 487000 Tel: 0191 385 2435 Tel: 01969 600120 Tel: 01642 710742 SITUATION AND AMENITIES Crab House lies in a particularly attractive spot to the south In addition to the farmstead and paddock there may be an Crab House has an area of garden ground to the front and west of the village of Healey in Colsterdale, about 4 miles to the opportunity to add additional land up to about 15 acres and more extensive, partially-walled garden area, to the south. west of Masham and within the Nidderdale AONB. At the end further details are available from the Selling Agents. of the no-through lane known as Breary Bank is the historic site FARM BUILDINGS It has accommodation on two floors and includes: of Breary Banks (Colsterdale) Camp. This was originally a site In addition to the adjoining stone byres there are further stone buildings offering more potential and although no for workers of the Leeds Corporation Reservoir Company but Ground Floor – living room, dining room, sitting room, planning enquiries have been specifically made, it is believed was requisitioned during the Great War as a training camp for kitchen, utility and shower room. -

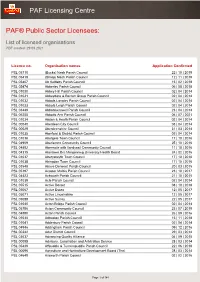

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

Nidderdale AONB State of Nature 2020

Nidderdale AONB State of Nature 2020 nidderdaleaonb.org.uk/stateofnature 1 FORWARD CONTENTS Forward by Lindsey Chapman Contents I’m proud, as Patron of The Wild Only by getting people involved 4 Headlines Watch, to introduce this State of in creating these studies in large Nature report. numbers do we get a proper 5 Our commitments understanding of what’s happening Growing up, I spent a lot of time in our natural world now. Thanks 6 Summary climbing trees, wading in streams to the hundreds of people and crawling through hedgerows. who took part, we now know 8 Background to the Nidderdale AONB I loved the freedom, adventure more than ever before about State of Nature report and wonder that the natural the current state of Nidderdale world offered and those early AONB’s habitats and wildlife. 14 Overview of Nidderdale AONB experiences absolutely shaped While there is distressing news, who I am today. such as the catastrophic decline 17 Why is nature changing? of water voles, there is also hope As a TV presenter on shows like for the future when so many Lindsey Chapman 30 Local Action and people TV and Radio Presenter the BBC’s Springwatch Unsprung, people come together to support The Wild Watch Patron Habitat coverage Big Blue UK and Channel 5’s their local wildlife. 43 Springtime on the Farm, I’m 46 Designated sites passionate about connecting This State of Nature report is just people with nature. The more a start, the first step. The findings 53 Moorland we understand about the natural outlined within it will serve world, the more we create as a baseline to assess future 65 Grassland and farmland memories and connections, the habitat conservation work. -

A Summary of Agri-Environment Project Activities

A summary of agri-environment project activities Thank you to everyone for providing their email address so collaborative working can continue. Arnside and Reviewing and increasing our database of farmers, foresters and land Helen Rawlinson [email protected] Silverdale AONB managers in the AONB. Short survey to gain info on desire for local network. 2 or 3 newsletters via post for those difficult to reach. 1-2-1 advice clinic either via internet or if risk assessment allows in person particularly around hedges and boundary CS. Blackdown Hills This will be a joint approach between Blackdown Hills and Dorset AONBs. We Gavin Saunders [email protected] AONB propose a nested approach based on 3 stages: Stage 1: Questionnaire using Survey Monkey, sent to existing Facilitation Fund members, FWAG SW membership, ELM Test & Trial cluster participants, etc. Aim for at least 25 responses. Questionnaire will assess current uptake of agri- environment schemes, timing of agreement endings, levels of satisfaction, understanding of agricultural transition proposals and their implications; determine what level of support farmers need for ELM, and what role the AONBs could serve. Stage 2: In-depth Farmer Interviews to a subset of c.12 farmers. Stage 3: Ensure participants attend NAAONB online webinars in March 2021. Final report with recommendations for future provision of advice within the AONB area. The project will be carried out by a consortium of three consultants: FWAG SW, Gavin Saunders and George Greenshields . Broads Authority Collaborating of Broads National Park and three AONBs (Norfolk Coast, Suffolk Andrea Kelly [email protected] Coast and Dedham Vale) to create a Natural Capital Compendium for each Protected Landscape, drawing on datasets compiled for the Norfolk and Suffolk Natural Capital Evidence Compendium. -

5 Date: 4Th March 2020 Report: Making Space for Nature Written By

Item No: 5 Date: 4th March 2020 Report: Making Space for Nature Written by: Rob Fairbanks _____________________________________________________________________ 1. Purpose of Report To inform Members of the work on the Test and Trail of the new Environmental Land Management Scheme. 2. Future Farming and the Environmental Land Management (ELM) Schemes Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) is a new programme working partners, landowners and farmers to help deliver Defra’s Future Farming ambitions that were outlined in the 25 Year Environment Plan. In 2024, Defra plans to launch the new Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS). It will be piloted from 2021 and the existing Direct Payments regime will be phased out. This new approach is not a subsidy. Those who are awarded ELM agreements will be paid public money in return for providing environmental benefits, including: Thriving plants and wildlife Enhanced landscapes and access Mitigation and adaptation measures (inc flooding) Clean air, water and reduce pollution 3. Farming for the Nation. The Surrey Hills Making Space for Nature project is part of the Defra Tests and Trials work known as 'Farming for the Nation' taking place within twelve AONBs. The AONBs will be testing new ways for Defra to incentivise environmentally friendly approaches to farming. The projects vary across the different AONBs according to landscape type, but all: incorporate an approach which encourages collaboration between the farmers and land managers involved; baseline natural capital and ecosystems services; incorporate nature-friendly farming approaches into farm business plans, land management plans and AONB Management Plans; and report on the impact of new approaches. The 12 AONBs involved are Blackdown Hills AONB, Cornwall AONB, Cranbourne Chase AONB, Dorset AONB, East Devon AONB, Forest of Bowland AONB, Kent Downs AONB, Nidderdale AONB, North Pennines AONB, Quantock Hills AONB, Surrey Hills AONB, and Tamar Valley AONB. -

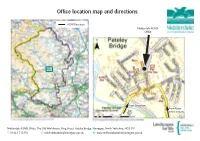

Office Location Map and Directions

Office location map and directions AONB Boundary Nidderdale AONB Office From Greenhow From Ripon and Harrogate Nidderdale AONB Office, The Old Workhouse, King Street, Pateley Bridge, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG3 5LE T: 01423 712950 E: [email protected] W: [email protected] Directions From Harrogate and Ripon Car parking Enter Pateley Bridge and come down the high street. At the bottom of the There is a small car park to the rear of the AONB office and this is free high street the road widens, before the river bridge. Turn right here and for visitors to the AONB office and Nidderdale Museum. Please do not follow the road round to the right and then up the hill. You will pass the park in the three yellow bays at the far end of the car park. primary school on your left and the police station will be on your right near the top of the hill, before you reach the church. The AONB office There is also a small amount of space for parking on the roadside outside can be found on your left, opposite the police station, through the large the AONB office. double blue doors. Public transport From Greenhow Pateley Bridge is accessible via the Transdev Harrogate & District number As you drop down the hill into Pateley Bridge, pass a row of shops on 24 bus service. This is a regular service which runs from Harrogate bus your left and then continue past the play area on your left. Go over the station (located next to Harrogate train station). -

National Survey Locations & Main Links in Local Supply

National Survey Locations & Main Links in Local Supply Chains Click on location to go to detailed map Hexham ! Penrith Darlington ! ! Otley Burnley ! ! Sheffield Knutsford ! Newark on Trent ! Birstall, Leicester ! ! ! ! Shrewsbury ! ! Kenilworth Norwich ! Ely Faversham Ledbury ! ! ! ! Hastings ! Yeovil Haslemere Totnes Reproduced from Ordnance Survey digital map data © Crown copyright 2012. All rights reserved. Licence numbers 100047514, 0100031673. LUC LDN 4964-01_021_National_Map_Final_NoComplexLinks 06/06/2012 Map Scale @ A3: 1:2,000,000 Key Supply chain links Boundary of local food supply area Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) National Park Settlements 0 2040 km ² Local supply chain into Hexham / Key Local food producers !u Meat/Processed meat ! Cereals ! Dairy Rothbury Northumberland National Park !B Fruit/Vegetables !d Eggs ! Fish/Shellfish !0³ Drinks ! Preserves !3 Baked goods ! Other Ashington Supply chain links Bellingham # Multistage supply chain link Boundary of core study area Boundary of local food supply area Cramlington Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) National Park Settlements Newcastle upon Tyne Brampton Hexham Sunderland Carlisle 5 miles Consett 10 miles Durham 15 miles Langwathby Spennymoor North Pennines AONB 20 miles Bishop Auckland Appleby 25 miles 30 miles Core study area and location of main local food outlets in Hexham Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2011 Local supply chain into Penrith / Key Local food producers !u Meat/Processed meat Northumberland ! Cereals -

Land Use Change in Protected Landscapes (Aonbs and National Parks): a Guide to the Tabulations

A Report Prepared For Defra Land Use Change in Protected Landscapes (AONBs and National Parks): A Guide to the Tabulations (LAND USE CHANGE INDICATORS FOR PROTECTED AREAS) February 2014 Department of Town and Regional Planning University of Sheffield Land Use Change in Protected Landscapes (AONBs and National Parks): A Guide to the Tabulations 1 Introduction 1.1 This document stands alongside a series of tabulations (University of Sheffield, 2013) that are designed to capture aspects of physical development in protected landscapes in the period since 1985. The present document provides a commentary on those Tabulations, exploring the relationships between the outcomes which they summarise and the operation of the planning system. Some supplementary tables are included to assist in this, which are styled Table S1, S2 etc to distinguish them from those in the principal document (Table 1, Table 2 which are also referred to here) 1.2 The tabulations themselves rest on two principal sources. The first is Ordnance Survey's Land Use Change Statistics (LUCS), which provides a very fine-grained view of land use changes observed in the course of updating the national survey base. The second is Royal Mail's Post Code address file (PAF) which is used to provide supplementary information about the changing numbers of properties. Together they provide a highly detailed picture of the changing pattern of built development in England's protected landscapes and elsewhere so we can track both the areal extent of change, and the density of development. 1.3 To appreciate both the strengths and limitations of the tabulations, it is important to understand the nature of the Land Use Change Statistics. -

Introduction Nidderdale Is Probably the Least Known of the Major Yorkshire Dales

Introduction Nidderdale is probably the least known of the major Yorkshire Dales. It is wedged between the two great valleys of Wharfedale and Wensleydale, and is the most eastern of all the dales. Although outside the Yorkshire Dales National Park, in 1994 it was designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in recognition of its exceptional landscape. The Nidderdale AONB covers 233 square miles (603 square km), has a population of 17,700 and includes part of Wensleydale, lower Wharfedale and the Washburn Valley. Nidderdale is unique among the dales in having three large bodies of water – the reservoirs of Gouthwaite, Scar House and Angram – linked by the River Nidd, whose name means ‘brilliant’ in Celtic. It also boasts impressive natural features such as Brimham Rocks, Guise Clif and How Stean Gorge. The lower dale is a domesticated landscape with lush pastures, gentle hills and plentiful woods with scattered farms and villages. The upper dale is bleaker, with sweeping horizons and desolate heather covered moors. Author Paul Hannon justly describes Nidderdale as a ‘jewel of the Dales’. Over its 54 miles (87 km), the Nidderdale Way takes you through the fnest walking in this little known valley. Gouthwaite Reservoir and dam 4 1 Planning and preparation The Nidderdale Way is a waymarked long-distance walk that makes a 54 mile (87 km) circuit of the valley of the River Nidd. Almost all of the Way lies within the boundaries of the Nidderdale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB): for the history of the route, see page 70. Although not a National Trail, it is marked by the Ordnance Survey (OS).