Global Audio Revolution the Music Has Changed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Start a Successful Podcast and Optimize Your Youtube Channel About Us

How To Start a Successful Podcast and Optimize your YouTube Channel About Us John Maher VP Multimedia and Digital Marketing McDougall Interactive • Over 15 years experience in SEO and digital marketing • Recording and podcast engineer • Video editor and YouTube optimizer • Musician • Worked in radio at WEZE in Boston About Us Rachel Popa Web Content Specialist The National Law Review • Former editor/reporter for Chicago Woman Magazine and Becker's Healthcare • Currently Web Content Specialist at The National Law Review • Optimize hundreds of podcast and video submissions from contributors to natlawreview.com How to Start a Successful Podcast What is podcasting? • Comes from the words “iPod” and “broadcasting” • An audio recording, like a radio show • Available for download or streaming from a website • Usually also downloadable automatically via RSS RSS = Really Simple Syndication A web feed that allows users and applications to access updates to websites Photo by Patrick Breitenbach / Creative Commons "rss" by TEIA MG is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Why Podcasting? • Less Competition – 570 Million blogs (7M posts daily) – 500 Hours added to YouTube every Minute – Only about 850,000 podcasts • Smartphones make podcasts accessible to millions of people – 32% of Americans listen at least monthly • Able to listen while at work, driving, running, at the gym, etc. • Your voice connects you personally to your Photo by Kai Chan Vong / Creative Commons audience • Connects you to experts and influencers in your industry Why Podcasting? % of US population -

Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point February 2019 for Private Circulation Only

Audio OTT economy in India – Inflection point February 2019 For Private circulation only Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point Contents Foreword by IMI 4 Foreword by Deloitte 5 Overview - Global recorded music industry 6 Overview - Indian recorded music industry 8 Flow of rights and revenue within the value chain 10 Overview of the audio OTT industry 16 Drivers of the audio OTT industry in India 20 Business models within the audio OTT industry 22 Audio OTT pie within digital revenues in India 26 Key trends emerging from the global recorded music market and their implications for the Indian recorded music market 28 US case study: Transition from physical to downloading to streaming 29 Latin America case study: Local artists going global 32 Diminishing boundaries of language and region 33 Parallels with K-pop 33 China case study: Curbing piracy to create large audio OTT entities 36 Investments & Valuations in audio OTT 40 Way forward for the Indian recorded music industry 42 Restricting Piracy 42 Audio OTT boosts the regional industry 43 Audio OTT audience moves towards paid streaming 44 Unlocking social media and blogs for music 45 Challenges faced by the Indian recorded music industry 46 Curbing piracy 46 Creating a free market 47 Glossary 48 Special Thanks 49 Acknowledgements 49 03 Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point Foreword by IMI “All the world's a stage”– Shakespeare, • Global practices via free market also referenced in a song by Elvis Presley, economics, revenue distribution, then sounded like a utopian dream monitoring, and reducing the value gap until 'Despacito' took the world by with owners of content getting a fair storm. -

Download the Podcast App for My PC Download the Podcast App for My PC

download the podcast app for my PC Download the podcast app for my PC. Download Anchor - Make your own podcast on PC. Anchor - Make your own podcast. Features of Anchor - Make your own podcast on PC. Stop worrying about overcharges when using Anchor - Make your own podcast on your cellphone, free yourself from the tiny screen and enjoy using the app on a much larger display. From now on, get a full-screen experience of your app with keyboard and mouse. MEmu offers you all the surprising features that you expected: quick install and easy setup, intuitive controls, no more limitations of battery, mobile data, and disturbing calls. The brand new MEmu 7 is the best choice of using Anchor - Make your own podcast on your computer. Coded with our absorption, the multi-instance manager makes opening 2 or more accounts at the same time possible. And the most important, our exclusive emulation engine can release the full potential of your PC, make everything smooth and enjoyable. Screenshots & Video of Anchor - Make your own podcast PC. Download Anchor - Make your own podcast on PC with MEmu Android Emulator. Enjoy playing on big screen. Anchor is the easiest way to make a podcast, brought to you by Spotify. Game Info. Anchor is the easiest way to make a podcast, brought to you by Spotify. Now you can create your podcast, host it online, distribute it to your favorite listening platforms, grow your audience, and monetize your episodes—all from your phone or tablet, for free. A RECORDING STUDIO IN YOUR POCKET: Record audio from anywhere, on any device. -

Meccanismi Di Creazione E Appropriazione Del Valore Nell’Industria Discografica

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004 ) in Economia e Gestione delle Aziende Tesi di Laurea Meccanismi di creazione e appropriazione del valore nell’industria discografica Relatore Ch. Prof. Francesco Zirpoli Correlatore Ch. Prof.ssa Elena Rocco Laureando Filippo Stocco Matricola 836333 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 Ad Enrico 1 INTRODUZIONE ......................................................................................... 6 1.L’INDUSTRIA DISCOGRAFICA .......................................................... 11 1.1 Introduzione: l’ industria musicale .................................................................................... 11 1.2 L’industria discografica..................................................................................................... 13 1.2.1 Descrizione: major vs indie ........................................................................................ 13 1.2.2 L’organizzazione dell’industria discografica ............................................................. 17 1.2 La filiera produttiva musicale italiana, dati e andamento............................................ 24 1.3 Il mercato discografico globale ................................................................................... 29 2. EVOLUZIONE E IMPATTO DELLA TECNOLOGIA SULL’INDUSTRIA DISCOGRAFICA ..................................................... 35 2.1.Storia ed evoluzione dell’industria discografica ............................................................... 35 2.1.2 Innovazioni incrementali interne -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

Pwnit and Ownit

Security Now! Transcript of Episode #814 Page 1 of 26 Transcript of Episode #814 PwnIt and OwnIt Description: This week we start with some needed revisiting of previous major topics. We look at an additional remote port that Chrome will soon be blocking, and the need to change server ports if you're using it. We look again at Google's forthcoming FLoC non- tracking technology and a new test page put up by the EFF. We revisit the PHP GIT server hack now that it's been fully understood. We look at Cisco's eyebrow-raising decision not to update some end-of-life routers having newly revealed critical vulnerabilities, and we also examine another instance of the industry's failure to patch for years. Then, we conclude with a blow-by-blow, or hack-by-hack, walkthrough of last week's quite revealing and somewhat chilling Pwn2Own competition. High quality (64 kbps) mp3 audio file URL: http://media.GRC.com/sn/SN-814.mp3 Quarter size (16 kbps) mp3 audio file URL: http://media.GRC.com/sn/sn-814-lq.mp3 SHOW TEASE: It's time for Security Now!. Steve Gibson is here with the answer to some critical questions. Why are Firefox and Chrome blocking port 10080, hmm? We'll also talk about FLoC, Google's Federated Learning of Cohorts technology. It's starting to roll out now, and he has a good way of figuring out if you're in the FLoC. And then it's a look at Pwn2Own, some fun exploits, some not-so- fun problems. -

Claimed Studios Self Reliance Music 779

I / * A~V &-2'5:~J~)0 BART CLAHI I.t PT. BT I5'HER "'XEAXBKRS A%9 . AFi&Lkz.TKB 'GMIG'GCIKXIKS 'I . K IUOF IH I tt J It, I I" I, I ,I I I 681 P U B L I S H E R P1NK FLOWER MUS1C PINK FOLDER MUSIC PUBLISH1NG PINK GARDENIA MUSIC PINK HAT MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PINK 1NK MUSIC PINK 1S MELON PUBL1SHING PINK LAVA PINK LION MUSIC PINK NOTES MUS1C PUBLISHING PINK PANNA MUSIC PUBLISHING P1NK PANTHER MUSIC PINK PASSION MUZICK PINK PEN PUBLISHZNG PINK PET MUSIC PINK PLANET PINK POCKETS PUBLISHING PINK RAMBLER MUSIC PINK REVOLVER PINK ROCK PINK SAFFIRE MUSIC PINK SHOES PRODUCTIONS PINK SLIP PUBLISHING PINK SOUNDS MUSIC PINK SUEDE MUSIC PINK SUGAR PINK TENNiS SHOES PRODUCTIONS PiNK TOWEL MUSIC PINK TOWER MUSIC PINK TRAX PINKARD AND PZNKARD MUSIC PINKER TONES PINKKITTI PUBLISH1NG PINKKNEE PUBLISH1NG COMPANY PINKY AND THE BRI MUSIC PINKY FOR THE MINGE PINKY TOES MUSIC P1NKY UNDERGROUND PINKYS PLAYHOUSE PZNN PEAT PRODUCTIONS PINNA PUBLISHING PINNACLE HDUSE PUBLISHING PINOT AURORA PINPOINT HITS PINS AND NEEDLES 1N COGNITO PINSPOTTER MUSIC ZNC PZNSTR1PE CRAWDADDY MUSIC PINT PUBLISHING PINTCH HARD PUBLISHING PINTERNET PUBLZSH1NG P1NTOLOGY PUBLISHING PZO MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PION PIONEER ARTISTS MUSIC P10TR BAL MUSIC PIOUS PUBLISHING PIP'S PUBLISHING PIPCOE MUSIC PIPE DREAMER PUBLISHING PIPE MANIC P1PE MUSIC INTERNATIONAL PIPE OF LIFE PUBLISHING P1PE PICTURES PUBLISHING 882 P U B L I S H E R PIPERMAN PUBLISHING P1PEY MIPEY PUBLISHING CO PIPFIRD MUSIC PIPIN HOT PIRANA NIGAHS MUSIC PIRANAHS ON WAX PIRANHA NOSE PUBL1SHING P1RATA MUSIC PIRHANA GIRL PRODUCTIONS PIRiN -

Download on Our Platform and We Have Obtained Licenses from Many Content Providers

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F (Mark One) ¨ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 or x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2013. or ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to or ¨ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission file number: 000-51469 Baidu, Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Cayman Islands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Baidu Campus No. 10 Shangdi 10th Street Haidian District, Beijing 100085 The People’s Republic of China (Address of principal executive offices) Jennifer Xinzhe Li, Chief Financial Officer Telephone: +(86 10) 5992-8888 Email: [email protected] Facsimile: +(86 10) 5992-0000 Baidu Campus No. 10 Shangdi 10th Street, Haidian District, Beijing 100085 The People’s Republic of China (Name, Telephone, Email and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered American depositary shares (ten American depositary shares representing one Class A ordinary share, The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC par value US$0.00005 per share) (The NASDAQ Global Select Market) Class A ordinary shares, par value US$0.00005 per share* The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC (The NASDAQ Global Select Market) * Not for trading, but only in connection with the listing on The NASDAQ Global Select Market of American depositary shares. -

Metamorphosis a Pedagocial Phenomenology of Music, Ethics and Philosophy

METAMORPHOSIS A PEDAGOCIAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF MUSIC, ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY by Catalin Ursu Masters in Music Composition, Conducting and Music Education, Bucharest Conservatory of Music, Romania, 1983 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education © Catalin Ursu 2009 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall, 2009 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Podcasts, According to an Advertiser Perceptions Study Commissioned by CUMULUS MEDIA | Westwood One

From highly personalized niche programs to brand extensions from major media networks, podcasting is where millions of media consumers are turning for information, entertainment, and connection to the world. In fact, an estimated 80 million Americans have listened to a podcast in the past week, according to The Infinite Dial 2021 from Edison Background Research and Triton Digital. Advertisers are taking notice of this substantial audience. Two out of three advertising media decision makers have discussed advertising in podcasts, according to an Advertiser Perceptions study commissioned by CUMULUS MEDIA | Westwood One. The huge interest from brands and agencies surrounding podcast audiences has raised questions like… 2 Major questions • How has the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic changed podcast listening over the last year? • Which genres of content have experienced the greatest growth? • What will the impact of Apple’s new subscription solution be on the podcast industry? • Is Clubhouse a podcast competitor or reach extender? CUMULUS MEDIA AND SIGNAL HILL INSIGHTS' PODCAST DOWNLOAD – SPRING 2021 REPORT 3 To answer these questions and more, CUMULUS MEDIA | Westwood One and Signal Hill Insights commissioned a study of weekly podcast listeners with MARU/Matchbox, a nationally recognized leader in consumer research. The sixth installment in the series, this report includes questions trended back to the inaugural 2017 study. As new questions have been added over the years, trending dates may differ. This also marks the second study released since -

Media/Entertainment Rise of Webtoons Presents Opportunities in Content Providers

Media/Entertainment Rise of webtoons presents opportunities in content providers The rise of webtoons Overweight (Maintain) Webtoons are emerging as a profitable new content format, just as video and music streaming services have in the past. In 2015, webtoons were successfull y monetized in Korea and Japan by NAVER (035420 KS/Buy/TP: W241,000/CP: W166,500) and Kakao Industry Report (035720 KS/Buy/TP: W243,000/CP: W158,000). In late 2018, webtoon user number s April 9, 2020 began to grow in the US and Southeast Asia, following global monetization. This year, NAVER Webtoon’s entry into Europe, combined with growing content consumption due to COVID-19 and the success of several webtoon-based dramas, has led to increasing opportunities for Korean webtoon companies. Based on Google Trends Mirae Asset Daewoo Co., Ltd. data, interest in webtoons is hitting all-time highs across major regions. [Media ] Korea is the global leader in webtoons; Market outlook appears bullish Jeong -yeob Park Korea is the birthplace of webtoons. Over the past two decades, Korea’s webtoon +822 -3774 -1652 industry has created sophisticated platforms and content, making it well-positioned for [email protected] growth in both price and volume. 1) Notably, the domestic webtoon industry adopted a partial monetization model, which is better suited to webtoons than monthly subscriptions and ads and has more upside potent ial in transaction volume. 2) The industry also has a well-established content ecosystem that centers on platforms. We believe average revenue per paying user (ARPPU), which is currently around W3,000, can rise to over W10,000 (similar to that of music and video streaming services) upon full monetization. -

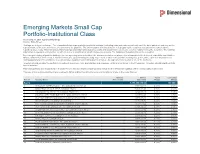

Emerging Markets Small Cap Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings Are Subject to Change

Emerging Markets Small Cap Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. This fund operates as a feeder fund in a master-feeder structure and the holdings listed below are the investment holdings of the corresponding master fund. Your use of this website signifies that you agree to follow and be bound by the terms and conditions of use in the Legal Notices.