Connecting Chord Progressions with Specific Pieces of Music Ivan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

Metamorphosis a Pedagocial Phenomenology of Music, Ethics and Philosophy

METAMORPHOSIS A PEDAGOCIAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF MUSIC, ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY by Catalin Ursu Masters in Music Composition, Conducting and Music Education, Bucharest Conservatory of Music, Romania, 1983 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education © Catalin Ursu 2009 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall, 2009 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Community Services Report 2011-2012

Community Services Report 2011-2012 1 2 MISSION 2 INTRODUCTION 3-8 PROGRAMS AND IMPACT 8-9 COMMUNITY FEEDBACK 9-12 FUNDRAISING INITIATIVES 12 FINANCES AND SUPPORTERS 13 CONTACT AND CONNECT MISSION MusiCares provides a safety net of critical assistance for music people in times of need. MusiCares’ services and resources cover a wide range of financial, medical and personal emergencies, and each case is treated with integrity and confidentiality. MusiCares also focuses the resources and attention of the music industry on human service issues that directly impact the health and welfare of the music community. 2 Over the past fiscal year, MusiCares served its largest number of clients to date providing more than $3 million in aid to approximately 3,000 clients. INTRODUCTION The Recording Academy established MusiCares in 1989 to provide the music community with a lifesaving safety net in times of need. We experience a great demand for the range of services we provide — from emergency financial assistance to addiction recovery resources, and this past year has been no exception. It is our ability to meet these increasing needs that speaks to the inherent generosity of music makers, from major artists to young industry professionals. As you read our stories from the past fiscal year (Aug. 1 – July 31), please take a moment to reflect on the generosity of the exceptional supporters of MusiCares, and consider making a gift to help our ongoing work to provide a safety net of services for music people in need. musicares.org • musicares.org • musicares.org • musicares.org • musicares.org • musicares.org • musicares.org • musicares.com • musicares.com • musicares.com • musicares.com • musicares.com PROGRAMS AND IMPACT ince its inception, MusiCares has developed into a premier support system for music people by providing innovative programs and services designed to meet the specific needs of its constituents. -

Global Audio Revolution the Music Has Changed

15 February 2019 Global EQUITIES Global Audio Revolution 40,000 10.0% The music has changed 30,000 5.0% 0.0% 20,000 -5.0% 10,000 -10.0% Key points 0 -15.0% 2007 2015 2006 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2016 2017 2018E 2019E 2020E 2005 The convergence of advertising and consumer direct spend on audio entertainment disrupts broadcast radio in favour of streaming platforms. Recorded music Radio Audiobook But the golden age of recorded music is behind us. Audiobooks and Streamcasts Audio yoy (RHS) podcasts are gaining share, undermining labels’ competitive position. Source: IFPI, Magna, APA, IAB, Macquarie Inside Our top picks are companies building a competitive advantage in the wider audio entertainment space: TME, SPOT and SIRI. Underperform on VIV. Table of contents 3 Exec summary 5 New models in audio entertainment Redefining audio entertainment 16 Recorded music is to audio what films are to video entertainment. It’s premium Freemium convergence 20 content, but it only represents 36% of the total 2018E audio revenues in the US. Streaming revolution 29 OTT is the first technology that brings together all audio content (music, Content-distribution equilibrium disrupted 36 audiobooks and radio/podcasts) on a single distribution platform. And it reunites advertising revenues with consumers’ direct spend (downloads/ subscriptions). Vertical integration appeal/necessity 40 Further disruption comes from a new type of integration achieved by TME (social/ The buoyant Chinese market 42 entertainment ecosystem) and by Amazon (e-commerce/entertainment plus voice Smart speakers and voice platforms 46 platform). Our new global audio entertainment model 50 Streamcasts and audiobooks rise, music slows Regulation 53 We argue our holistic approach allows new investment opportunities: 1) Ad revenues shift from broadcast radio to on-demand streaming - We expect commercial radio advertising to decline as streaming platforms grow into podcasts, the equivalent of unscripted TV shows in parallel with video Analysts content. -

MUSIKFÖRLÄGGAREN NR 3 2007 1 Ledare

M 03/2007USIKFÖRLÄGGARENNr 3 2007 ARVET EFTER: Thore Ehrling Nya marknader i sikte Rekordår för klubben Den digitala marknaden MUSIKFÖRLÄGGAREN NR 3 2007 1 Ledare Den digitala ljudfilen har i grunden förändrat frågor som kan uppstå i samband med en viss hur musik exploateras och distribueras. Detta ny teknisk applikation, innan man kan erbju- har i sin tur givit upphov till en explosions- da en licensieringslösning. I ett sådan situation artad framväxt av en ny marknad för musik. kan man helt enkelt behöva ta till en interims- Där radion, TV-n och grammofonskivan tidi- lösning för att komma vidare. De upphovsmän gare var de dominerande ljudmedierna (ljud- vi företräder förväntar sig med rätta att vi på bärare brukade man säga förr) för inspelad bredast möjliga sätt tillvaratar det värde deras musik, tar nu exempelvis mp3-spelare, digitala musik representerar. Särskilt som musiken ofta butiker som iTunes, hemsidor med nedladd- är det som säljer även hårdvaran, exempelvis ningsbar musik och mobiltelefoner över en allt mobiltelefonerna. större del av distributionen. För att uppnå detta krävs kunskap, kunskap I detta nya landskap räcker det för oss mu- och åter kunskap; om den grundläggande tek- sikförläggare inte med en viss nyorientering nologin, om rättighetsjuridiken, om marknads- eller anpassning till nya förhållanden. Tvärtom segmenten, om licensieringsmetoderna mm. måste vi vara med och aktivt leda utveckling- Inom SMFF kommer vi därför och för lång FOTO: Peter Hallbom en, utifrån intresset för den musik vi företräder. tid framöver att arbeta intensivt – både internt Men vi måste också ha beredskap för en helt och externt liksom hemma och internationellt annan flexibilitet än tidigare. -

Free Magazines Download in PDF for Ipad/PC

Now1,Alitlstour Excuse for ThatHeap. NevernundtJustHurl Me Into TheRoadAndPut Me OutOfMe Miiers. FIRSTENTERTAINMENT CREDITUNION AnAlternative Wayto Book www.firstent.org/gnome 888.800.3328 ADVERTISEMENT storemags.com riiim4k401111W7f..0";-'- r-47:,JeWOREP.r-XYLLriMPH .1 "._ -=;=irlev SomeThings Get BetterWith Age. aril ourCar... NotSoMuch. Wheneventhe lawnornamentscringe at the sight of your carcomingupthe driveway,youknow it's time for a newride. The goodnewsis, foralimited time,your neighborsat First EntertainmentCredit Union haveauto loanratesaslowas1.49% APR: Rates this low don't comearoundeveryday. And they won't last forever either. So don't delay, do yourself andyourgarden friendsafavor and apply today. Visit www.firstent.org/gnome, call 888.800.3328 orstop byabranchtoapply. FIRSTENTERTAINMENT mimmCREDITUNION AnAlternative Wayto Bankk MPR=AnnualPercentope Rae 1.49% APR is rite preferred rate fornewvehicles up. dB months atomonthly payment of approximately 521.48per51000 borrowed. Add:banal roles, slattingaslowas1.95% APR, end Berms may apply, roll 8813 /500.3328 for details. Rate of 1.491 APR is olso tlx prelerredrote for used Irricnernumage6yearsold) vehiclesup to48 months atamonthly payment of approximately 521.481per51,000 borrowed. Amount financedmay notevrned the Ad5R8or110% al the lugh Kelley Blue Book NADA value farnew(100% IN used), trcluding lax, kens, GAP Insurance and Mechanical BreakdownProtection. Roles tab.ct . charge without now,. No additronol discounts may be applied la these roles. All loons sabred to creole approval Existing Fast Enlerroinmen1auto loom may norbe refinanced under the terms of this offer. Offer expires June 30, 2013. c 20124 Few, I0 Gale Una, irdixami 06.22.2013billboard.combillboard.biz FIRST DRAFT OF STARDOM At Work With Demo Singers DUMB IT DOWN How To Grow Digital PANDORA COMES TO EARTH Latest Royalty Tactic THE PRICE OF GOLD After 7 million albums, she's readyto start over."IfyouputDolly Parton, Adele and Juicy J together, you'd have it." LIFE FLIES BY IN AN INSTANT, LET'S PROTECT THE MEN WE LOVE. -

Superventas España 22-02-2015

TOP 100 CANCIONES + STREAMING (Las ventas totales corresponden a los datos enviados por colaboradores habituales de venta física y por los siguientes operadores: Amazon, Buongiorno, Gran Vía Musical, Google Play, i-Tunes, Jetmultimedia, Media Markt online, Movistar, Orange, Vodafone, Nokia, Zune, 7Digital, Deezer, Spotify, Xbox Music y Napster) SEMANA 08: del 16.02.2015 al 22.02.2015 Sem. Sem. Pos. Sem. Cert. Actual Ant. Max. Lista Artista Título Sello Promus. 1 ▲ 5 5 2 ELLIE GOULDING LOVE ME LIKE YOU DO - FROM FIFTY SHADES OFUNIVERSAL GREY 2 ▼ 1 1 11 MARK RONSON FEAT. BRUNO MARS UPTOWN FUNK SONY MUSIC * 3 ● 3 2 15 ED SHEERAN THINKING OUT LOUD WARNER MUSIC GROUP * 4 ▲ 28 28 2 NICKY JAM EL PERDÓN SONY MUSIC 5 ▼ 4 3 28 NICKY JAM TRAVESURAS CODISCOS ** 6 ▲ 8 8 5 DASOUL ÉL NO TE DA ROSTER MUSIC 7 ▲ 22 22 4 THE WEEKND EARNED IT (FIFTY SHADES OF GREY) UNIVERSAL 8 ▼ 2 2 25 SAM SMITH STAY WITH ME UNIVERSAL ** 9 ▲ 12 9 9 OSMANI GARCIA / PITBULL / SENSATO EL TAXI URBAN LATIN RECORDS * 10 ▼ 7 1 20 DAVID GUETTA FEAT. SAM MARTIN DANGEROUS WARNER MUSIC GROUP ** 11 ▼ 6 3 33 SIA CHANDELIER SONY MUSIC 2** 12 ▼ 11 8 13 HOZIER TAKE ME TO CHURCH UNIVERSAL * 13 ▼ 9 1 24 JUAN MAGAN FEAT. BELINDA & LAPIZSI CONCIENTE NO TE QUISIERA UNIVERSAL ** 14 ▲ 21 19 6 SIA ELASTIC HEART SONY MUSIC 15 ▼ 10 10 14 CALVIN HARRIS FEAT. ELLIE GOULDINGOUTSIDE SONY MUSIC * 16 ▼ 13 13 9 SOFIA REYES FEAT. WISIN MUEVELO WARNER MUSIC GROUP 17 ▼ 16 2 25 MEGHAN TRAINOR ALL ABOUT THAT BASS SONY MUSIC ** 18 ▼ 14 5 9 MEGHAN TRAINOR LIPS ARE MOVIN SONY MUSIC * 19 ▼ 17 4 23 MELENDI TOCADO Y HUNDIDO WARNER MUSIC GROUP ** 20 ▼ 18 16 11 AVICII THE NIGHTS UNIVERSAL 21 ▼ 19 19 9 JUAN MAGAN FEAT. -

Repertorio Administrado

ASOCIACIÓN GUATEMALTECA DE GESTIÓN DE LA INDUSTRIA DE PRODUCTORES DE FONOGRAMAS Y AFINES A continuación, se presenta el Listado de Asociados, Repertorio Registrado y Administrado por AGINPRO: UNIVERSAL MÚSICA DE CENTROAMÉRICA, S.A. • ℗ 1977 Umg Recordings, Inc. • Ak7 Corp. Exclusively Licensed In The • ℗ 1993 Fonovisa Records United States To Universal Music Group • ℗ 2018 Dj Snake Music Productions • Alamo Records / Interscope Limited, Under Exclusive License To • All Around The World Geffen Records • Andaluz Music - Banda Carnaval • 10 Summers Records/Interscope Records • Andaluz Records Distributed By Universal • 10:22 Pm Music Group • 10:22 Pm / Universal Music Group (De • Andaluz Records/Disa/Umle Umle) • Andres Saavedra • 1510 Certified Ent/300 Entertainment And • Andy Rivera Universal Music Group • Aura Music • 2015 Discos Fuentes • Aura Music Corp. • 2017 Mia Musa • Bad Gyal Aftercluv/Interscope • 2018 Discos Fuentes • Banda El Recodo P&D • 2018 Flow La Movie, Inc. • Beartrap/ Alamo/ Interscope Records • 2018 Flow La Movie, Inc., Distributed By • Beartrap/ Alamo/Universal Music Group Glad Empire • Benny Blanco Major • 2019 Casablanca Records & One World • Benny Blanco Solo Album Ps Music | Distributed By Glad Empire • Big Hit Entertainment • 2019 Flow La Movie Inc | Distributed By • Boomshakalaka - Umle / Sony Benelux Glad Empire, Llc • Boy Toy, Inc. Exclusively Licensed To Live • 2019 Flow La Movie, Inc. | Distributed By Nation Worldwide, Inc. Exclusively Glad Empire, Llc. Licensed To Universal Music Group • 2020 Discos Fuentes • Boy Toy, Inc., Exclusively Licensed To • 2020 Flow La Movie, Inc. & Los Magicos, Live Nation Worldwide, Inc. Exclusively Llc | Powered By Glad Empire, Licensed To Interscope Records • 2020 Flow La Movie, Inc. | Powered By • Boy Toy, Inc., Exclusively Licensed To Glad Empire, Llc Live Nation Worldwide, Inc. -

AWP-06-2016 Date: June 2016

ACEI working paper series RESEARCHING SONG TITLES, PRODUCT CYCLES AND COPYRIGHT IN PUBLISHED MUSIC: PROBLEMS, RESULTS AND DATA SOURCES Ruth Towse Hyojung Sun AWP-06-2016 Date: June 2016 1 Researching song titles, product cycles and copyright in published music: problems, results and data sources Ruth Towse CIPPM, Bournemouth University and CREATe (University of Glasgow) [email protected] with research by Hyojung Sun CIPPM, Bournemouth University and University of Edinburgh hyojung Sun <[email protected]> Abstract The purpose of this Working Paper is to pass on our experience of research on song titles and product cycles in UK music publishing which was intended to provide evidence of the impact of copyright in a market. The Working Paper relates to the article ‘Economics of Music Publishing: Copyright and the Market’, published in the Journal of Cultural Economics, 2016. The context of the research was a project on copyright and business models in music publishing that was part of the AHRC funded project: the ‘Economic Survival in a Long Established Creative Industry: Strategies, Business Models and Copyright in Music Publishing’. By collecting data on the product cycles of a sample of long-lasting song titles and trying to establish changes in the product cycle as the copyright regime changed we had hoped to produce empirical evidence on the effect changes in the copyright regime, such as term extension, or to those in copyright management organisations. For a variety of reasons, this proved impossible to do (at least in the UK) and the Working Paper explains what we think were the reasons. -

61St Annual Critics Poll

D O W N B E AT 61st Annual Critics Poll 61ST A NNUAL CRITI C S POLL /// W AYNE AYNE S HORTER WINS! Jazz /// CHARLIE CHARLIE ARTIST Jazz H ALBUM A D Jazz Without A Net EN /// R GROUP O B Wayne Shorter ERT JOHNSON ERT Quartet Soprano SAX /// CHRISTIAN M Hall of Fame Charlie Haden C BRI Robert Johnson D E Poll Winners Wadada Leo Smith Christian McBride Gregory Porter AUGUST 2013 U.K. £3.50 Gerald Clayton Tia Fuller AU G UST Top 2013 91 DOWNBEAT.COM Albums AUGUST 2013 VOLUME 80 / NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Maggie Glovatski Cuprisin 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Winter 2019-20/2

Second Thoughts and Short Reviews Winter 2019-2020/2 By Brian Wilson, Dan Morgan and Johan van Veen Reviews are by Brian Wilson unless otherwise stated. Winter #1 is here and Autumn 2019 #2 here. Index [page numbers in brackets; later page numbers may be slightly displaced] BACH Six Partitas for harpsichord (Clavier Übung I) - Ton Koopman_Challenge Classics [7] - Cantatas Nos. 82, 84 and 199 – Christine Schäfer_Sony [7] BANTOCK Violin Sonata No.3; SCOTT Viola Sonata; SACHEVERELL COKE Violin Sonata No.1 - Rupert Marshall-Luck; Matthew Rickard_EM Records [20] BARTH, GADE, KUHLAU – 19th Century Danish Overtures - Aarhus Symphony Orchestra/Jean Thorel _DaCapo [14] BEETHOVEN 250 – new and old releases_Various performers and labels [10] - Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5 – Rudolf Brautigam; Kölner Akademie/Michael Willens_BIS [12] - Late String Quartets – Cypress Quartet_Avie [13] - String Quartet No.14 – Jaspere Quartet_Sono Luminus [13] BERNARDI Lux æterna – Voces Suaves_Arcana [3] BRIDGE Phantasie for string quartet; HOLST Phantasy on British Folksongs; GOOSSENS Phantasy Quartet for strings; HOWELLS Phantasy String Quartet; HOLBROOKE First Quartet Fantasie; HURLSTONE Phantasie for string quartet - The Bridge Quartet_EM Records [19] BUXTEHUDE Membra Jesu Nostri - RossoPorpora Ensemble/Testolin_Stradivarius[4] CIMAROSA 21 Organ Sonatas – Andrea Chezzi_Brilliant Classics [10] COLONNA O splendida dies – Scherzi Musicali/Achten_Ricercar [5] DUKAS L’Apprenti Sorcier; Polyeucte Overture – Loire Orchestra/Pascal Rophé_BIS (with ROUSSEL) [17] ELGAR Violin Sonata: see GURNEY GESUALDO Madrigals – Exaudi Ensemble/Weeks_Winter and Winter [3] GOOSSENS Phantasy Concerto for Violin and Orchestra; Symphony No.2 – Tasmin Little; Melbourne SO/Andrew Davis_Chandos [20] GÓRECKI Symphony No.3 – Adeliade SO/Yuasa_ABC [22] GURNEY Violin Sonata in E-flat; SAINSBURY Soliloquy for Solo Violin; ELGAR Violin Sonata - Rupert Marshall-Luck; Matthew Rickard (piano)_EM Records [19] HAYDN Symphonies Nos. -

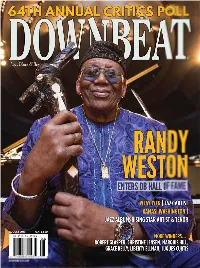

Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected]

August 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael