A CRITICAL REVIEW of the ROMAN ATRIUM HOUSE: READING the MATERIAL EVIDENCE on “ATRIUM” (1) Kemal Reha KAVAS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUILDING CONSTRUCTION NOTES.Pdf

10/21/2014 BUILDING CONSTRUCTION RIO HONDO TRUCK ACADEMY Why do firefighters need to know about Building Construction???? We must understand Building Construction to help us understand the behavior of buildings under fire conditions. Having a fundamental knowledge of buildings is an essential component of the decisiondecision--makingmaking process in successful fireground operations. We have to realize that newer construction methods are not in harmony with fire suppression operations. According to NFPA 1001: Standard for FireFighter Professional Qualifications Firefighter 1 Level ––BasicBasic Construction of doors, windows, and walls and the operation of doors, windows, and locks ––IndicatorsIndicators of potential collapse or roof failure ––EffectsEffects of construction type and elapsed time under fire conditions on structural integrity 1 10/21/2014 NFPA 1001 Firefighter 2 Level ––DangerousDangerous building conditions created by fire and suppression activities ––IndicatorsIndicators of building collapse ––EffectsEffects of fire and suppression activities on wood, masonry, cast iron, steel, reinforced concrete, gypsum wallboard, glass and plaster on lath Money, Money, Money….. Everything comes down to MONEY, including building construction. As John Mittendorf says “ Although certain types of building construction are currently popular with architects, modern practices will be inevitably be replaced by newer, more efficient, more costcost--effectiveeffective methods ”” Considerations include: ––CostCost of Labor ––EquipmentEquipment -

The Legend of Romulus and Remus

THE LEGEND OF ROMULUS AND REMUS According to tradition, on April 21, 753 B.C., Romulus and his twin brother, Remus, found Rome on the site where they were suckled by a she-wolf as orphaned infants. Actually, the Romulus and Remus myth originated sometime in the fourth century B.C., and the exact date of Rome’s founding was set by the Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro in the first century B.C. According to the legend, Romulus and Remus were the sons of Rhea Silvia, the daughter of King Numitor of Alba Longa. Alba Longa was a mythical city located in the Alban Hills southeast of what would become Rome. Before the birth of the twins, Numitor was deposed by his younger brother Amulius, who forced Rhea to become a vestal virgin so that she would not give birth to rival claimants to his title. However, Rhea was impregnated by the war god Mars and gave birth to Romulus and Remus. Amulius ordered the infants drowned in the Tiber, but they survived and washed ashore at the foot of the Palatine hill, where they were suckled by a she-wolf until they were found by the shepherd Faustulus. Reared by Faustulus and his wife, the twins later became leaders of a band of young shepherd warriors. After learning their true identity, they attacked Alba Longa, killed the wicked Amulius, and restored their grandfather to the throne. The twins then decided to found a town on the site where they had been saved as infants. They soon became involved in a petty quarrel, however, and Remus was slain by his brother. -

Livy's View of the Roman National Character

James Luce, December 5th, 1993 Livy's View of the Roman National Character As early as 1663, Francis Pope named his plantation, in what would later become Washington, DC, "Rome" and renamed Goose Creek "Tiber", a local hill "Capitolium", an example of the way in which the colonists would draw upon ancient Rome for names, architecture and ideas. The founding fathers often called America "the New Rome", a place where, as Charles Lee said to Patrick Henry, Roman republican ideals were being realized. The Roman historian Livy (Titus Livius, 59 BC-AD 17) lived at the juncture of the breakdown of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. His 142 book History of Rome from 753 to 9 BC (35 books now extant, the rest epitomes) was one of the most read Latin authors by early American colonists, partly because he wrote about the Roman national character and his unique view of how that character was formed. "National character" is no longer considered a valid term, nations may not really have specific national characters, but many think they do. The ancients believed states or peoples had a national character and that it arose one of 3 ways: 1) innate/racial: Aristotle believed that all non-Greeks were barbarous and suited to be slaves; Romans believed that Carthaginians were perfidious. 2) influence of geography/climate: e.g., that Northern tribes were vigorous but dumb 3) influence of institutions and national norms based on political and family life. The Greek historian Polybios believed that Roman institutions (e.g., division of government into senate, assemblies and magistrates, each with its own powers) made the Romans great, and the architects of the American constitution read this with especial care and interest. -

Geodesic Dome Roof

GEODESIC DOME ROOF The HMT Geodesic Dome features a clear-span, all-aluminum, lightweight, corrosion-resistant structure which sets a new standard for performance in aluminum geodesic domes. HMT’s unique overlapping-panel design and attention to details at critical locations all result in a cost-effective solution that provides superior protection of your stored product. The HMT Geodesic Dome can be installed in-service and its superior design was developed under the guidance of API 650, appendix G and AWWA D-108. Key benefits: Key design features: The HMT Geodesic Dome’s advanced tBatten bar and gasket assembly completely technology provides excellent benefits. Here’s encapsulate panel edges for unparallelled how: sealing Most effective leak-protection solution— tOverlapping panels ensure additional Engineered for maximum weather-tightness for protection against weather both new tanks and retrofits tHub designed with three levels of sealing to Low maintenance — Aluminum alloys are ensure maximum leak protection corrosion resistant and don’t require painting like steel fixed roofs tHub can be easily removed for inspection or Emissions reduction — reduces wind-induced adjustment of IFR support chains vapor loss, aids in odor control and provides tOptions for fixed or sliding rim connections significant emission credits; for light products such as gasoline, a dome installed over an EFR tCan easily handle the weight of suspended can cut emissions by over 90% aluminum internal floating roofs In-service installation — Can be erected on tIndustry-leading 3D design software for the ground beside the tank or on an EFR and maximum accuracy and shorter design time lifted into place Custom engineered— To accommodate a wide range of spans and loading conditions Protecting your world, one tank at a time™ www.hmttank.com THE HMT GEODESIC DOME DESIGN HMT’s design incorporates features which dramatically Triple seal hub design improve upon existing technology. -

Basic Technical Rules the Nubian Vault (Nv)

PRODUCTION CENTRE INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME BASIC TECHNICAL RULES v3 BASIC TECHNICAL RULES THE NUBIAN VAULT (NV) TECHNICAL CONCEPT THE NUBIAN VAULT ASSOCIATION (AVN) ADVICE TO MSA CLIENTS Version 3.0 SEASON 2013-2014 COUNTRY INTERNATIONAL Association « la Voûte Nubienne » - 7 rue Jean Jaurès – 34190 Ganges - France February 2015 www.lavoutenubienne.org / [email protected] / +33 (0)4 67 81 21 05 1/14 PRODUCTION CENTRE INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME BASIC TECHNICAL RULES v3 CONTENTS CONTENTS.............................................................................................................2 1.AN ANCIENT TECHNIQUE, SIMPLIFIED, STANDARDISED & ADAPTED.........................3 2.MAIN FEATURES OF THE NV TECHNIQUE........................................................................4 3.THE MAIN STAGES OF NV CONSTRUCTION.....................................................................5 3.1.EXTRACTION, FABRICATION & TRANSPORT OF MATERIAL....................................5 3.2.CHOOSING THE SITE....................................................................................................5 3.3.MAIN STRUCTURAL WORKS........................................................................................6 3.3.1.Foundations........................................................................................................................................ 6 3.3.2.Load-bearing walls.............................................................................................................................. 7 3.3.3.Arches in load-bearing -

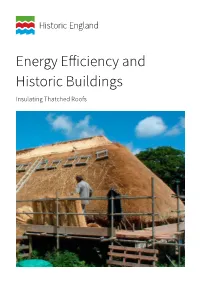

Insulating Thatched Roofs This Guidance Note Has Been Prepared and Edited by David Pickles

Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings Insulating Thatched Roofs This guidance note has been prepared and edited by David Pickles. It forms one of a series of thirteen guidance notes covering the thermal upgrading of building elements such as roofs, walls and floors. First published by English Heritage March 2012. This edition (v1.1) published by Historic England April 2016. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Illustrations drawn by Simon Revill. Our full range of guidance on energy efficiency can be found at: HistoricEngland.org.uk/energyefficiency Front cover: Thatch repairs in progress. © Philip White. Summary This guidance provides advice on the principles, risks, materials and methods for insulating thatched roofs. There are estimated to be about fifty thousand thatched buildings in England today, some of which retain thatch which is over six hundred years old. Thatching reflects strong vernacular traditions all over the country. Well-maintained thatch is a highly effective weatherproof coating as traditional deep thatched eaves will shed rainwater without the need for any down pipes or gutters. Locally grown thatch is a sustainable material, which has little impact on the environment throughout its life-cycle. It requires no chemicals to grow, can be harvested by hand or using traditional farm machinery, requires no mechanical processing and therefore has low embodied energy and can be fixed using hand tools. At the end of its life it can be composted and returned to the land. Thatch has a much greater insulating value than any other traditional roof covering. With the right choice of material and detailing, a well-maintained thatched roof will keep a building warm in winter and cool in summer and has the added advantage of being highly sound-proof. -

Millet Use by Non-Romans

Finding Millet in the Roman World Charlene Murphy, PhD University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gower Street, London, UK WC1H 0PY [email protected] Abstract Examining the evidence for millet in the Roman empire, during the period, circa 753BC-610AD, presents a number of challenges: a handful of scant mentions in the ancient surviving agrarian texts, only a few fortuitous preserved archaeological finds and limited archaeobotanical and isotopic evidence. Ancient agrarian texts note millet’s ecological preferences and multiple uses. Recent archaeobotanical and isotopic evidence has shown that millet was being used throughout the Roman period. The compiled data suggests that millet consumption was a more complex issue than the ancient sources alone would lead one to believe. Using the recent archaeobotanical study of Insula VI.I from the city of Pompeii, as a case study, the status and role of millet in the Roman world is examined and placed within its economic, cultural and social background across time and space in the Roman world. Millet, Roman, Pompeii, Diet Charlene Murphy Finding Millet in the Roman World 1 Finding Millet in the Roman World Charlene Murphy, PhD University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gordon Square, London, UK WC1H 0PY [email protected] “If you want to waste your time, scatter millet and pick it up again” ( moram si quaeres, sparge miliu[m] et collige) (Jashemski et al. 2002, 137). A proverb scratched on a column in the peristyle of the House of M. Holconius Rufus (VIII.4.4) at Pompeii Introduction This study seeks to examine the record of ‘millet’, which includes both Setaria italia (L.) P. -

Replacing the Roof on Your Manufactured Or Mobile Home Protectmymanufacturedhome

What You Should Know: Replacing the roof on your manufactured or mobile home ProtectMyManufacturedHome An alteration permit from the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries is required when you reroof a manufactured home. In some cases, plans for the work must also be submitted to L&I for approval prior to doing the work. L&I has a four-step process for home alterations. Here’s how: Step 1: See if you need to submit plans. You need to submit plans if: You are not removing the old shingles or roof covering before installing the new roofing. The new roof covering is heavier than the original. There are repairs to any roof framing, such as trusses or rafters. A second layer of sheathing or additional framing is added to the roof. Plans must be stamped by a Washington professional engineer (PE) or architect. When you reroof, you need to submit plans when buying a permit (see step 2). There is a fee for reviewing plans which is added to the permit. Get more information It usually takes two to three weeks to process plans and plans must be approved before proceeding with the work. Visit www.Lni.wa.gov/FAS You do not need to submit plans if: For structural issues, contact plan review at: 360-902-5218 You are removing the existing roofing and installing For general permit help, call customer new roofing of the same or lesser weight. service at: 360-902-5206 Existing roof sheathing may be removed and new roof Or email [email protected] sheathing used. -

Installers' Handbook Preface

HANDBOEK VOOR INSTALLATEURS Handboek voor de installatie van VELUX dakvensters Installers' handbook Preface The purpose of this handbook is to provide an overview of the installation of VELUX products. The handbook describes the various aspects of roof construction in association with VELUX roof windows and also provides advice and information on how to obtain the optimal installation. (Third edition, 2010) The VELUX system Chapter 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Other products Chapter 9 Contents Planning Considerations before choosing roof window 5-13 1 Installation of a roof window Installation step by step 15-25 2 Integration – more windows Combination of more than one window 27-45 3 Special installation conditions Installation in various roof constructions 47-63 4 Special roofing materials Installation in various roof materials 65-81 5 Replacement / renovation Replacement of a roof window 83-93 6 Building physics Roof constructions (humidity, heat, sound etc) 95-109 7 Product information Short presentation of VELUX products 111-137 8 Other products Sun tunnel / Flat roof window / Solar hot water system 139-145 9 Contact VELUX Addresses / Advising / Service 146-147 List of telephone numbers 148 Size chart 151 Planning 1 The construction of the house 6-7 User requirements 8 Building regulations 9-13 VELUX 5 Planning 1 The construction of the house To be able to choose the right VELUX roof window for a given situ- ation, it is always recommended to start from the construction of the house, user requirements and current building regulations. Normally, a standard VELUX roof window can satisfy the basic requirements, but often choosing another window type or vari- ant and/or choosing accessories can optimise the function and increase the utility value of the window. -

Varro's Roman Seasons

Varro’s Roman Seasons Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Varro’s Roman Seasons. 2019. hal-02387848 HAL Id: hal-02387848 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02387848 Submitted on 30 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. HAL, Submitted 30 November 2019 Varro's Roman Seasons A. C. Sparavigna1 1 Dipartimento di Scienza Applicata e Tecnologia, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy The four seasons of the Roman calendar, as described by Marcus Terentius Varro, are different from our seasons, in the sense that they start on days which differ from those that we are using today. In his Books on Agriculture, Varro shows that the Roman seasons started on the Cross Quarter-days instead than on the Quarter-days of the year as it happens today. Besides the classic subdivision in four parts, in the Books on Agriculture we can also find the year divided into eight parts, that is eight seasons having quite different lengths. In our discussion of Varro's seasons we will compare the days he mentions for the separation of seasons to the Cross Quarter- and Quarter-days that we find in Celtic calendars. -

Top-Operated Centre-Pivot Polyurethane Roof Window GLU 0061

Edition 2.0 – 05.04.2017 Product information Top-operated centre-pivot polyurethane roof window GLU 0061 Product description High quality moulded polyurethane with white lacquer finish Triple insulating glass unit with Uw 1.1 Top control bar for easy operation even with furniture under the window Integrated ventilation in top control bar and cleanable dust and insect filter Maintenance-free interior surface Maintenance-free exterior covers Roof pitch Can be installed in roof pitches between 15° and 90° Materials Polyurethane around a core of thermally modified timber Glass; float glass / strengthened glass / toughened glass Lacquered aluminium VELUX ThermoTechnology™ insulation Downloads For installation instructions, CAD drawings, 3D BIM objects, 3D GDL objects etc, please visit velux.bg. Certifications The VELUX product EUTR In compliance with the EU Timber factories guarantee Regulation (EUTR), EU regulation quality systems 995/2010 implementation process and environmental REACH We are aware of the REACH regulation management systems and acknowledge the obligations. No through appropriate products are obliged to be registered in accreditations ISO accordance to REACH and none of our 9001 and ISO 14001 products contain any Substances of Very High Concern. Available sizes and daylight area Lining measurements 472 550 660 mm 780 mm 942 mm 1140 mm 1340 mm Size Width (mm) mm mm GLU p CK-- 495 CK02 mm FK-- 605 78 7 (0.22) MK-- 725 GLU MK04 PK-- 887 m m SK-- 1085 78 9 (0.47) Size Height (mm) GLU GLU FK06 MK06 --02 719 m m --04 919 78 11 --06 1119 (0.47) (0.59) GLU GLU GLU GLU --08 1339 FK08 MK08 PK08 SK08 --10 1549 m 398 m 398 1 (0.58) (0.72) (0.92) (1.16) GLU MK10 1600mm (0.85) ( ) = Effective daylight area, m2 Top-operated centre-pivot roof windows make it possible to place furniture directly below the window without obstructing operation of the window. -

Lecture 19 Greek, Carthaginian, and Roman Agricultural Writers

Lecture 19 1 Lecture 19 Greek, Carthaginian, and Roman Agricultural Writers Our knowledge of the agricultural practices of Greece and Rome are based on writings of the period. There were an enormous number of writings on agriculture, although most of them are lost we know about them from references made by others. Theophrastus of Eresos (387–287 BCE) The two botanical treatises of Theophrastus are the greatest treasury of botanical and horticultural information from antiquity and represent the culmination of a millenium of experience, observation, and science from Egypt and Mesopotamia. The fi rst work, known by its Latin title, Historia de Plantis (Enquiry into Plants), and composed of nine books (chapters is a better term), is largely descriptive. The second treatise, De Causis Plantarum (Of Plants, an Explanation), is more philosophic, as indicated by the title. The works are lecture notes rather than textbooks and were presumably under continual revision. The earliest extant manuscript, Codex Urbinas of the Vatican Library, dates from the 11th century and contains both treatises. Although there have been numerous editions, translations, and commentaries, Theophrastus the only published translation in En glish of Historia de Plantis is by (appropriately) Sir Arthur Hort (1916) and of De Causis Plantarum is by Benedict Einarson and George K.K. Link (1976). Both are available as volumes of the Loeb Classical Library. Theophrastus (divine speaker), the son of a fuller (dry cleaner using clay), was born at Eresos, Lesbos, about 371 BCE and lived to be 85. His original name, Tyrtamos, was changed by Aristotle because of his oratorical gifts.