AWB Limited, and Its Affiliated Companies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of the Moratorium on Genetically Modified Canola in Victoria Published by the Victorian Government Department of Primary Industries, Melbourne, November 2007

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES Review of the moratorium on genetically modified canola in Victoria Published by the Victorian Government Department of Primary Industries, Melbourne, November 2007 © The State of Victoria, 2007 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwth). Authorised by: Victorian Government 1 Spring Street, Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia ISBN 978-1-74199-675-3 (print) ISBN 978-7-74199-676-0 (online) Disclaimer: This publication is copyright. Reproduction and the making available of this material for personal, in-house or non-commercial purposes is authorised, on condition that: • the copyright owner is acknowledged • no official connection is claimed • the material is made available without charge or at cost • the material is not subject to inaccurate, misleading or derogatory treatment. Requests for permission to reproduce or communicate this material in any way not permitted by this licence (or by the fair dealing provisions of the Copyright Act 1968) should be directed to the Customer Service Centre, 136 186 or email [email protected]. For more information about DPI visit the website at www.dpi.vic.gov.au or call the Customer Service Centre on 136 186. 30 October 2007 Minister for Agriculture Victoria Dear Minister As members of the independent Review of the moratorium on genetically modified canola in Victoria, we are pleased to submit our report to you. We would like to thank all those who took part in the Review by either providing submissions or other information to us or taking part in consultations. -

Grower Representation and Its Impact on the Governance Structure of the Australian Grains Industry Terence C Farrell Α

Grower Representation and its Impact on the Governance Structure of the Australian Grains Industry Terence C Farrell α Abstract The Australian wheat industry has changed considerably in structure and governance during the past 15 years. The most important changes have been the deregulation of the domestic market and privatisation of the former Australian Wheat Board into AWB Limited. Through these changes growers have become shareholders in the various companies. Governance of the monopsonistic relationship between AWB Limited and AWB International by the Federal Minister of Agriculture and the Grains Council of Australia through the Wheat Export Authority has proved ineffective. Hence a national organisation that represents shareholders is recommended to increase grower governance of the supply chain and marketing of wheat. Key Words: Grain, Marketing, Infrastructure, Competition and Governance. The presentation of this paper was sponsored by Grain Growers Association. The views presented in this paper are strictly those of the author and may not coincide with the views or opinions of Grain Growers Association or its members. Contributed paper presented to the 48th Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society Conference, Melbourne, February 11-13, 2004. I would like to thank Alistair Watson for useful information and comments. α Terence Farrell, 11 Cynthia Crescent, Armidale, NSW 2350. Phone 02 6771 2093. Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Page Introduction…………………………………………………………………………1 Background………………………………………………………………………….2 Path to Deregulation………………………………………………………………...2 Railway Companies.…..…………………………………………………………….5 Ports…………………………………………………………………………………7 Industry Governance………………………………………………………………...8 The Role of the Federal Minister for Agriculture…………………………………..11 Growers Representation…………………………………………………………….12 The New Structure………………………………………………………………….13 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………..15 Tables Page Table 1. Selected Changes in the Bulk Handling Industry 1989-2003.……………4 Table 2. -

Annual Report 1998-1999.Pdf (PDF, 3.37MB)

VISION AND MISSION IFC CENTRE OBJECTIVES 3 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 4 MANAGING DIRECTOR’S REPORT 6 STRUCTURE AND MANAGEMENT 10 COOPERATIVE LINKAGES 14 RESEARCH PROGRAM 1 16 PROGRAM 2 29 PROGRAM 3A 37 PROGRAM 3B 41 PROGRAM 4 45 PROGRAM 5 51 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 61 UTILISATION, COMMERCIALISATION AND LINKS 69 STAFFING AND ADMINISTRATION 71 PATENTS, PUBLICATIONS, GRANTS AND AWARDS 72 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 76 1 MAJORMAJOR ACHIEVEMENTSACHIEVEMENTS ANDAND OUTCOMESOUTCOMES PROGRAM 1 PROGRAM 2 I A new method for detecting molecular I Commercial launch of the WheatRite test markers to accelerate wheat breeding. for rain damage. I New wheat germplasm with major I Improved quality at harvest and receival: benefits for processors and consumers. agronomy and storage procedures developed for growers and users. PROGRAM 3 PROGRAM 4 I Aids for the management of microbe I Methods for the rapid assessment of the contamination in wheat and flour mills. shelf-life of frozen dough products. I Enhanced process control in bakeries I Product quality improvements; knowledge leading to cost savings and superior of the effects of different starches and products. other ingredients on bread, pasta and noodles. PROGRAM 5 EDUCATION & TRAINING I New equipment and methods to evaluate I Multiple advisory aids provided to growers. wheat and flour properties. Great Grain quality assurance scheme I Quality tests to accelerate wheat piloted. breeding. I Tertiary educated scientists and technologists enter the industry, 2 Develop new wheats and new products. Develop improved diagnostic -

Ublic Policy Cover-8

50993 Public Policy Text 25/7/07 1:47 PM Page 44 PUBLIC POLICY VOLUME 2 NUMBER 1 2007 44 – 57 Deregulating Australia's Wheat Trade: from the Australian Wheat Board to AWB Limited Geoff Cockfield University of Southern Queensland Linda Courtenay Botterill The Australian National University In 2006 in Australia there was an inquiry into allegations of kickbacks being paid to the former Iraqi regime by the grain trading company AWB Limited. The inquiry and its aftermath provided an opportunity for proponents of unregulated trade in wheat to press for the removal of the AWB’s control of export sales. This article is a review of the history of the development and dismantling of wheat marketing regulation in Australia, treated as a case study to illustrate two things: the shift in the prevailing values in Australian agricultural policy over the last 35 years; and the way in which legislative cycles, reviews, institutional change and particular events provide opportunities for policy advocates to press for change, in this case over at least 40 years. It is argued here that the dominant paradigm for trading agricultural commodities shifted from one based on agrarian collectivism and sectoral stabilisation to a less regulated system with the focus on the values of efficiency and competitiveness. In November 2005 the Australian Government established an inquiry with the powers of a Royal Commission headed by Terence Cole to investigate allegations that the corporation AWB Limited1 (formerly the statutory authority Australian Wheat Board) had made payments to Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq through a Jordanian-based transport company in order to secure wheat sales, accusations originally raised by the UN Oil-for-Food inquiry headed by Paul Volker. -

Australian Wheat Varieties: Grain Quality Data on Recently Registered Varieties

VALUE ADDED WHEAT CRC PROJECT REPORT Australian Wheat Varieties: Grain Quality Data on Recently Registered Varieties Compiled by: G.B. Cornish1,2 I.L. Batey1,3 and C.W. Wrigley1,3 1 Value Added Wheat CRC Ltd, North Ryde, NSW 2 SARDI Grain Quality Research Laboratory, Adelaide, S.A. 3 Food Science Australia, North Ryde, NSW Date: October 2002 VAWCRC Report No: 8 Copy No: 79 CONFIDENTIAL (Not to be copied) Value Added Wheat CRC has taken all reasonable care in preparing this publication. Value Added Wheat CRC expressly disclaims all and any liability to any person for any damage, loss or injury (including economic loss) arising from their use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Australian Wheat Varieties: Grain Quality Data on Recently Registered Varieties G.B.Cornish1, 2 I.L.Batey1, 3, and C.W.Wrigley1, 3 1Value-Added Wheat CRC, North Ryde, NSW 2SARDI Grain Quality Research Laboratory, Adelaide, South Australia, and 3Food Science Australia, North Ryde, NSW This report provides quality data on wheat varieties that have recently been registered, thereby supplementing an earlier report, entitled ‘Current Australian Wheat Varieties: Grain Quality Data’, by Wrigley et al. (2001), published as Report No 48 of the Quality Wheat CRC. Also provided in this report is an up-dated table of attributes and genes relevant to grain quality (Table 1), plus a list of the grades to which specific varieties are acceptable in the 2002/3 harvest (Table 2.). Refer to the earlier report for an explanation of the genes described in this up-dated version. -

Using Digital Image Analysis for Assessing the Quality of Wheat and Barley

Using Digital Image Analysis for Assessing the Quality of Wheat and Barley Bruce Gordon Armstrong Bachelor of Applied Science (Honours) Master of Applied Science Thesis This Thesis is Submitted to Fulfil the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science by Research School of Science and Engineering University of Ballarat PO Box 663 University Drive, Mt. Helen Ballarat, Victoria 3353 Australia Submitted in December 2004 Abstract This thesis explores the issues involved in developing a relatively low-cost Digital Imaging Analysis (DIA) system for the quality assessment of wheat and barley using commonly available equipment. It also explores the capability of such a system to provide rapid and accurate assessments. The research confirms that it is possible to devise such a system using flatbed scanners for image capture and conventional personal computers for the image analysis. However, it is necessary to modify the scanners, place them in a cabinet and develop special indented trays to hold the grain samples for optimal results. It is also necessary to develop complex software to undertake the analysis. The small sample sizes and non-destructive DIA methods will be especially beneficial to grain breeders and others who only have limited amounts of grain to work with. The DIA system developed (SeedCount) is capable of making very accurate counts of grain, and thus produces accurate thousand kernel weight assessments. Initially these counts were totally dependent on a novel (now patented) counting algorithm. The system can also make accurate morphological measurements of the kernel length, width and area that are limited in accuracy primarily by the image’s resolution. -

An Economic Analysis of Removing the Canadian Wheat Board's Single

An Economic Analysis of Removing the Canadian Wheat Board’s Single Desk Authority and Rail Deregulation in Western Canada by Janelle Wallace A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Agribusiness and Agricultural Economics University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2011 by Janelle Wallace Abstract Wheat is the most common cereal crop grown by farmers in Western Canada and is mainly used for export. The marketing structure for wheat in Western Canada is unique. The Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), a statutory marketing board, is mandated to sell all wheat grown by farmers for human consumption in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Peace River region of British Columbia. Using historical price and basis data, this research attempts to quantify the economics of the current marketing structure for wheat in Western Canada. Simulations are developed to determine the economic profits and risk that could have been realized in an open market considering scenarios for three potential changes in the grain handling and transportation system (GHTS) and four alternative marketing strategies. Each are evaluated using a utility-based risk model to ascertain the most preferred marketing environment in terms of expected profit and risk. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Fabio Mattos (Department of Agribusiness and Agricultural Economics, University of Manitoba), for all your guidance during this research and for always making time for me. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Jared Carlberg (Department of Agribusiness and Agricultural Economics, University of Manitoba), for encouraging me to pursue my education further and guiding me through the graduate studies program. -

Role of the Seed Coat in the Dormancy of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum) Grains

Role of the Seed Coat in the Dormancy of Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Grains Submitted by Judith Rebecca Rathjen This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of Plant and Food Science School of Agriculture, Food and Wine Faculty of Sciences University of Adelaide, Waite Campus Glen Osmond, South Australia, 5064, Australia September, 2006 Statement of Authorship This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference being made in the text of the thesis. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Libraries being available for photocopying and loan. Judith Rebecca Rathjen September, 2006 ii Table of Contents Statement of Authorship...................................................................................................ii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................iii Acknowledgements ..........................................................................................................ix Abstract ............................................................................................................................x General Introduction........................................................................................................1 -

Submission to the Senate Inquiry Into Operational Issues Arising in the Export Grain Storage, Transport, Handling and Shipping Network

Submission to the Senate Inquiry into Operational issues arising in the export grain storage, transport, handling and shipping network 12 May 2011 GrainCorp Operations Limited Level 26, 175 Liverpool Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A268, Sydney South NSW 1235 T: 02 9325 9100 F: 02 9325 9180 www.graincorp.com.au ABN 52 003 875 401 Table of Contents Terms of Reference ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Structure of this submission ................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Responses to matters raised ............................................................................................................................... 5 Matter A .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Provision of access to the GrainCorp storage and handling network ......................................................... 5 Port elevators as ‘essential infrastructure’ ................................................................................................. 6 Provision of access to the GrainCorp port elevator network ..................................................................... -

Wheat Export Marketing Arrangements Public Inquiry

Draft report on wheat export marketing arrangements: AWB Limited’s Response AWB submission to the Productivity Commission on the draft report on Wheat Export Marketing Arrangements Introduction AWB appreciates this additional opportunity and would offer the key observation that the transition process for the industry is still underway. While further evolution is going to occur, this review offers a timely opportunity to highlight areas where undesirable developments are occurring that are, and will, continue to impede the operation of fair and efficient market mechanisms as well as identify many positive developments or areas for further improvement. As a large export participant in both bulk and container sales with a large number of international and domestic customers, AWB has the benefit of experience of operating across all port zones at the local level during this transitional period. AWB strongly maintains the view that there is a role for the continuation of an amended Wheat Export Marketing Act 2008, to ensure port terminal access protocols remain in force and ensures access to certain sources of information is maintained for the long term benefit of the Australian wheat industry. However AWB supports the Productivity Commission’s recommendation that the operation of the current Wheat Export Accreditation System is not required beyond September 30, 2011. Chapter 3 - Marketing and Pricing Draft finding 3.1 (p 49) The key drivers of the export price of wheat (and the recent commodity price cycle) are: - the global demand, supply and stocks of wheat - the exchange rate - relative transport costs from Australia (and other exporting countries) to export markets. -

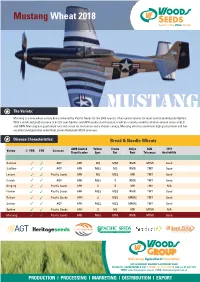

Mustang Wheat 2018 a Part of the Group

Mustang Wheat 2018 A part of the Group mustang The Variety: Mustang is a new wheat variety being released by Pacific Seeds for the 2018 season. It has quick maturity for main season planting like Spitfire. With a predicted yield increase of 6-12% over Spitfire, and APH quality classification, it will be a variety suited to all main season areas of QLD and NSW. Mustang has good stripe rust and crown rot resistance and a shorter canopy. Mustang also has consistent high grain protein and has excellent yield potential under Root Lesion Nematode (RLN) pressure. Disease Characteristics: Bread & Noodle Wheats AWB Limited Yellow Crown Stripe RLN 2018 Variety PBR EPR Licensee Classification Spot Rot Rust Tolerance Availability Sunmax AGT APH MS MSS RMR MTMI Good Suntime AGT APH MSS MS RMR TMT Good Lancer Pacific Seeds APH MS MSS MR TMT Good Coolah AGT APH MSS S RMR TMT Good Gregory Pacific Seeds APH S S MR TMT N/A Flanker Pacific Seeds APH MSS MSS RMR TMT Good Reliant Pacific Seeds APH S MSS MRMS TMT Good Suntop AGT APH MSS MSS MRMS TMT Good Spitfire Pacific Seeds APH S MS MR MTMI N/A Mustang Pacific Seeds APH MSS MSS RMR MTMI Good the power to grow Delivering Agricultural Innovation CNR LEICHHARDT HIGHWAY & BOUNDARY ROAD PO BOX 135, GOONDIWINDI Q 4390 | PHONE: +61 07 4670 0400 | FAX: +61 07 4671 3907 EMAIL: [email protected] | WEB: www.woodsgrain.com.au PRODUCTION l PROCESSING l MARKETING l DISTRIBUTION l EXPORT Mungbeans : Mungbeans will again be available in good supply for the 2017/2018 Spring and Summer Crops. -

Australian Government Review of the Wheat Marketing Act 1989, December 2000

NATIONAL COMPETITION POLICY REVIEW OF THE WHEAT MARKETING ACT 1989 Mr Malcolm Irving AM Mr Jeff Arney Professor Bob Lindner December 2000 © Commonwealth of Australia 2000 ISBN 0 642 76904 4 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Secretary, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, GPO Box 858, Canberra ACT 2601. Published by the NCP - WMA Review Committee GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Copies are available from: Shopfront Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia (Freecall telephone number 1 800 020 157) Foreword FOREWORD This review of the Wheat Marketing Act 1989 (the WMA) was conducted under the National Competition Policy (NCP), which was agreed to by all Australian Governments in 1995. Under this agreement, Australian governments are to review all legislation that affects competition, and to complete these reviews by the end of 2000. On 4 April 2000 the Honourable Warren Truss MP, Federal Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, announced the NCP review of the WMA. When announcing the review, the Minister directed the Committee to focus on those parts of the legislation which restrict competition, and impose costs or confer benefits on businesses involved in the Australian wheat industry and the community generally. The independent review Committee appointed by the Minister comprised Mr Malcolm Irving, Mr Jeff Arney and Professor Bob Lindner.