Novel Technique to Identify Large River Host Fish for Freshwater Mussel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquatic Fish Report

Aquatic Fish Report Acipenser fulvescens Lake St urgeon Class: Actinopterygii Order: Acipenseriformes Family: Acipenseridae Priority Score: 27 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Gobal Rank: G3G4 — Vulnerable (uncertain rank) State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Ouachita Mountains Arkansas Valley South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Acipenser fulvescens Lake Sturgeon 362 Aquatic Fish Report Ecobasins Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - Arkansas River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - St. Francis River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - White River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (Lake Chicot) - Mississippi River Habitats Weight Natural Littoral: - Large Suitable Natural Pool: - Medium - Large Optimal Natural Shoal: - Medium - Large Obligate Problems Faced Threat: Biological alteration Source: Commercial harvest Threat: Biological alteration Source: Exotic species Threat: Biological alteration Source: Incidental take Threat: Habitat destruction Source: Channel alteration Threat: Hydrological alteration Source: Dam Data Gaps/Research Needs Continue to track incidental catches. Conservation Actions Importance Category Restore fish passage in dammed rivers. High Habitat Restoration/Improvement Restrict commercial harvest (Mississippi River High Population Management closed to harvest). Monitoring Strategies Monitor population distribution and abundance in large river faunal surveys in cooperation -

A Fish Habitat Partnership

A Fish Habitat Partnership Strategic Plan for Fish Habitat Conservation in Midwest Glacial Lakes Engbretson Underwater Photography September 30, 2009 This page intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. BACKGROUND 7 II. VALUES OF GLACIAL LAKES 8 III. OVERVIEW OF IMPACTS TO GLACIAL LAKES 9 IV. AN ECOREGIONAL APPROACH 14 V. MULTIPLE INTERESTS WITH COMMON GOALS 23 VI. INVASIVES SPECIES, CLIMATE CHANGE 23 VII. CHALLENGES 25 VIII. INTERIM OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS 26 IX. INTERIM PRIORITY WATERSHEDS 29 LITERATURE CITED 30 APPENDICES I Steering Committee, Contributing Partners and Working Groups 33 II Fish Habitat Conservation Strategies Grouped By Themes 34 III Species of Greatest Conservation Need By Level III Ecoregions 36 Contact Information: Pat Rivers, Midwest Glacial Lakes Project Manager 1601 Minnesota Drive Brainerd, MN 56401 Telephone 218-327-4306 [email protected] www.midwestglaciallakes.org 3 Executive Summary OUR MISSION The mission of the Midwest Glacial Lakes Partnership is to work together to protect, rehabilitate, and enhance sustainable fish habitats in glacial lakes of the Midwest for the use and enjoyment of current and future generations. Glacial lakes (lakes formed by glacial activity) are a common feature on the midwestern landscape. From small, productive potholes to the large windswept walleye “factories”, glacial lakes are an integral part of the communities within which they are found and taken collectively are a resource of national importance. Despite this value, lakes are commonly treated more as a commodity rather than a natural resource susceptible to degradation. Often viewed apart from the landscape within which they occupy, human activities on land—and in water—have compromised many of these systems. -

2009 Land Management Plan

2009 LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN (Updated Annual Harvest Plan -2014) Itasca County Land Department 1177 LaPrairie Avenue Grand Rapids, MN 55744-3322 218-327-2855 ● Fax: 218-327-4160 LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Itasca County Land Department Acknowledgements This Land Management Plan was produced by Itasca County Land Department employees Garrett Ous, Dave Marshall, Michael Gibbons, Adam Olson, Bob Scheierl, Roger Clark, Kory Cease, Steve Aysta, Tim Stocker, Perry Leone, Wayne Perreault, Blair Carlson, Loren Eide, Bob Rother, Andrew Brown, Del Inkman, Darlene Brown and Meg Muller. Thank you to all the citizens for their sincere input and review during the public involvement process. And thank you to Itasca County Commissioners Lori Dowling, Karen Burthwick, Rusty Eichorn, Catherine McLynn and Mark Mandich for their vision and final approval of this document. Foreword This land management plan is designed for providing vision and direction to guide strategic and operational programs of the Land Department. That vision and direction reflects a long standing connection with local economic, educational and social programs. The Land Department is committed to ensuring that economic benefits and environmental integrity are available to both present and future generations. That will be accomplished through actively managing county land and forests for a balance of benefits to the citizens and for providing them with a sustained supply of quality products and services. The Department will apply quality forestland stewardship practices, employ modern technology and information, and partner with other forest organizations to provide citizens with those quality products and services. ________________________________ Garrett Ous September, 2009 Itasca County Land Commissioner 1177 LaPrairie Avenue Grand Rapids, MN 55744-3322 218-327-2855 ● Fax: 218-327-4160 ICLD - LMP Section i., page 1 of 3 Itasca County Land Department Land Management Plan Table of Contents i. -

Demography of Freshwater Mussels Within the Lower Flint River

DEMOGRAPHY OF FRESHWATER MUSSELS WITHIN THE LOWER FLINT RIVER BASIN, SOUTHWEST GEORGIA by JUSTIN C. DYCUS (Under the Direction of Robert Bringolf) ABSTRACT Environmental and spatial variation can potentially influence mussel populations through acute and chronic mechanisms. The objectives of this study were to identify and quantify the chronic factors affecting freshwater mussel growth. Live mussels were collected within the lower Flint River Basin, sacrificed, and their shells were thin-sectioned. Thin sections revealed the production of internal annuli, which were used to determine individual ages and estimate annual growth. I evaluated the relation between annual growth and presumed variables responsible for altering growth using mixed linear models. Growth was indicated to vary in relation to seasonal streamflow, species, age, tagging, channel confinement, and physiographic province. The effect of tagging should be accounted for in subsequent mark-recapture studies, and species- and site- specific characteristics should be considered when implementing management decisions to prevent future harm to freshwater mussel populations. INDEX WORDS: Thin Section, Annuli, Freshwater Mussel, Streamflow, Umbo, Villosa lienosa, Villosa vibex, Elliptio crassidens DEMOGRAPHY OF FRESHWATER MUSSELS WITHIN THE LOWER FLINT RIVER BASIN, SOUTHWEST GEORGIA By JUSTIN C. DYCUS A.S., Sandhills Community College, 2006 B.S., North Carolina State University, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2011 © 2011 JUSTIN CHARLES DYCUS All Rights Reserved DEMOGRAPHY OF FRESHWATER MUSSELS WITHIN THE LOWER FLINT RIVER BASIN, SOUTHWEST GEORGIA By JUSTIN C. DYCUS Major Professor: Robert Bringolf Committee: James T. -

Attachment J Assessment of Existing Paleontologic Data Along with Field Survey Results for the Jonah Field

Attachment J Assessment of Existing Paleontologic Data Along with Field Survey Results for the Jonah Field June 12, 2007 ABSTRACT This is compilation of a technical analysis of existing paleontological data and a limited, selective paleontological field survey of the geologic bedrock formations that will be impacted on Federal lands by construction associated with energy development in the Jonah Field, Sublette County, Wyoming. The field survey was done on approximately 20% of the field, primarily where good bedrock was exposed or where there were existing, debris piles from recent construction. Some potentially rich areas were inaccessible due to biological restrictions. Heavily vegetated areas were not examined. All locality data are compiled in the separate confidential appendix D. Uinta Paleontological Associates Inc. was contracted to do this work through EnCana Oil & Gas Inc. In addition BP and Ultra Resources are partners in this project as they also have holdings in the Jonah Field. For this project, we reviewed a variety of geologic maps for the area (approximately 47 sections); none of maps have a scale better than 1:100,000. The Wyoming 1:500,000 geology map (Love and Christiansen, 1985) reveals two Eocene geologic formations with four members mapped within or near the Jonah Field (Wasatch – Alkali Creek and Main Body; Green River – Laney and Wilkins Peak members). In addition, Winterfeld’s 1997 paleontology report for the proposed Jonah Field II Project was reviewed carefully. After considerable review of the literature and museum data, it became obvious that the portion of the mapped Alkali Creek Member in the Jonah Field is probably misinterpreted. -

A Review of the Systematic Biology of Fossil and Living Bony-Tongue Fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei)

Neotropical Ichthyology, 16(3): e180031, 2018 Journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ni DOI: 10.1590/1982-0224-20180031 Published online: 11 October 2018 (ISSN 1982-0224) Copyright © 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia Printed: 30 September 2018 (ISSN 1679-6225) Review article A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei) Eric J. Hilton1 and Sébastien Lavoué2,3 The bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha, have been the focus of a great deal of morphological, systematic, and evolutio- nary study, due in part to their basal position among extant teleostean fishes. This group includes the mooneyes (Hiodontidae), knifefishes (Notopteridae), the abu (Gymnarchidae), elephantfishes (Mormyridae), arawanas and pirarucu (Osteoglossidae), and the African butterfly fish (Pantodontidae). This morphologically heterogeneous group also has a long and diverse fossil record, including taxa from all continents and both freshwater and marine deposits. The phylogenetic relationships among most extant osteoglossomorph families are widely agreed upon. However, there is still much to discover about the systematic biology of these fishes, particularly with regard to the phylogenetic affinities of several fossil taxa, within Mormyridae, and the position of Pantodon. In this paper we review the state of knowledge for osteoglossomorph fishes. We first provide an overview of the diversity of Osteoglossomorpha, and then discuss studies of the phylogeny of Osteoglossomorpha from both morphological and molecular perspectives, as well as biogeographic analyses of the group. Finally, we offer our perspectives on future needs for research on the systematic biology of Osteoglossomorpha. Keywords: Biogeography, Osteoglossidae, Paleontology, Phylogeny, Taxonomy. Os peixes da Superordem Osteoglossomorpha têm sido foco de inúmeros estudos sobre a morfologia, sistemática e evo- lução, particularmente devido à sua posição basal dentre os peixes teleósteos. -

Copyrighted Material

06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 15 Phylum Chordata Chordates are placed in the superphylum Deuterostomia. The possible rela- tionships of the chordates and deuterostomes to other metazoans are dis- cussed in Halanych (2004). He restricts the taxon of deuterostomes to the chordates and their proposed immediate sister group, a taxon comprising the hemichordates, echinoderms, and the wormlike Xenoturbella. The phylum Chordata has been used by most recent workers to encompass members of the subphyla Urochordata (tunicates or sea-squirts), Cephalochordata (lancelets), and Craniata (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals). The Cephalochordata and Craniata form a mono- phyletic group (e.g., Cameron et al., 2000; Halanych, 2004). Much disagree- ment exists concerning the interrelationships and classification of the Chordata, and the inclusion of the urochordates as sister to the cephalochor- dates and craniates is not as broadly held as the sister-group relationship of cephalochordates and craniates (Halanych, 2004). Many excitingCOPYRIGHTED fossil finds in recent years MATERIAL reveal what the first fishes may have looked like, and these finds push the fossil record of fishes back into the early Cambrian, far further back than previously known. There is still much difference of opinion on the phylogenetic position of these new Cambrian species, and many new discoveries and changes in early fish systematics may be expected over the next decade. As noted by Halanych (2004), D.-G. (D.) Shu and collaborators have discovered fossil ascidians (e.g., Cheungkongella), cephalochordate-like yunnanozoans (Haikouella and Yunnanozoon), and jaw- less craniates (Myllokunmingia, and its junior synonym Haikouichthys) over the 15 06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 16 16 Fishes of the World last few years that push the origins of these three major taxa at least into the Lower Cambrian (approximately 530–540 million years ago). -

Fossil Fishes from the Miocene Ellensburg Formation, South Central Washington

FISHES OF THE MIO-PLIOCENE WESTERN SNAKE RIVER PLAIN AND VICINITY IV. FOSSIL FISHES FROM THE MIOCENE ELLENSBURG FORMATION, SOUTH CENTRAL WASHINGTON by GERALD R. SMITH, JAMES E. MARTIN, NATHAN E. CARPENTER MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, 204 no. 4 Ann Arbor, December 1, 2018 ISSN 0076-8405 PUBLICATIONS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 204 no.4 WILLIAM FINK, Editor The publications of the Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, consist primarily of two series—the Miscellaneous Publications and the Occasional Papers. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. Occasionally the Museum publishes contributions outside of these series. Beginning in 1990 these are titled Special Publications and Circulars and each are sequentially numbered. All submitted manuscripts to any of the Museum’s publications receive external peer review. The Occasional Papers, begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, initiated in 1916, include monographic studies, papers on field and museum techniques, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, and are published separately. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians, Fishes, Insects, Mollusks, and other topics is available. -

The Freshwater Bivalve Mollusca (Unionidae, Sphaeriidae, Corbiculidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina

SRQ-NERp·3 The Freshwater Bivalve Mollusca (Unionidae, Sphaeriidae, Corbiculidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina by Joseph C. Britton and Samuel L. H. Fuller A Publication of the Savannah River Plant National Environmental Research Park Program United States Department of Energy ...---------NOTICE ---------, This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neither the United States nor the United States Depart mentof Energy.nor any of theircontractors, subcontractors,or theiremploy ees, makes any warranty. express or implied or assumes any legalliabilityor responsibilityfor the accuracy, completenessor usefulnessofanyinformation, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. A PUBLICATION OF DOE'S SAVANNAH RIVER PLANT NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH PARK Copies may be obtained from NOVEMBER 1980 Savannah River Ecology Laboratory SRO-NERP-3 THE FRESHWATER BIVALVE MOLLUSCA (UNIONIDAE, SPHAERIIDAE, CORBICULIDAEj OF THE SAVANNAH RIVER PLANT, SOUTH CAROLINA by JOSEPH C. BRITTON Department of Biology Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas 76129 and SAMUEL L. H. FULLER Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Prepared Under the Auspices of The Savannah River Ecology Laboratory and Edited by Michael H. Smith and I. Lehr Brisbin, Jr. 1979 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 STUDY AREA " 1 LIST OF BIVALVE MOLLUSKS AT THE SAVANNAH RIVER PLANT............................................ 1 ECOLOGICAL -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

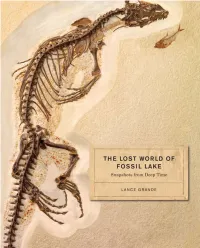

The Lost World of Fossil Lake

Snapshots from Deep Time THE LOST WORLD of FOSSIL LAKE lance grande With photography by Lance Grande and John Weinstein The University of Chicago Press | Chicago and London Ray-Finned Fishes ( Superclass Actinopterygii) The vast majority of fossils that have been mined from the FBM over the last century and a half have been fossil ray-finned fishes, or actinopterygians. Literally millions of complete fossil ray-finned fish skeletons have been excavated from the FBM, the majority of which have been recovered in the last 30 years because of a post- 1970s boom in the number of commercial fossil operations. Almost all vertebrate fossils in the FBM are actinopterygian fishes, with perhaps 1 out of 2,500 being a stingray and 1 out of every 5,000 to 10,000 being a tetrapod. Some actinopterygian groups are still poorly understood be- cause of their great diversity. One such group is the spiny-rayed suborder Percoidei with over 3,200 living species (including perch, bass, sunfishes, and thousands of other species with pointed spines in their fins). Until the living percoid species are better known, ac- curate classification of the FBM percoids (†Mioplosus, †Priscacara, †Hypsiprisca, and undescribed percoid genera) will be unsatisfac- tory. 107 Length measurements given here for actinopterygians were made from the tip of the snout to the very end of the tail fin (= total length). The FBM actinop- terygian fishes presented below are as follows: Paddlefishes (Order Acipenseriformes, Family Polyodontidae) Paddlefishes are relatively rare in the FBM, represented by the species †Cros- sopholis magnicaudatus (fig. 48). †Crossopholis has a very long snout region, or “paddle.” Living paddlefishes are sometimes called “spoonbills,” “spoonies,” or even “spoonbill catfish.” The last of those common names is misleading because paddlefishes are not closely related to catfishes and are instead close relatives of sturgeons. -

A Review of the Systematic Biology of Fossil and Living Bony-Tongue Fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei)" (2018)

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2018 A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony- tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei) Eric J. Hilton Virginia Institute of Marine Science Sebastien Lavoue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Hilton, Eric J. and Lavoue, Sebastien, "A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei)" (2018). VIMS Articles. 1297. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/1297 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neotropical Ichthyology, 16(3): e180031, 2018 Journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ni DOI: 10.1590/1982-0224-20180031 Published online: 11 October 2018 (ISSN 1982-0224) Copyright © 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia Printed: 30 September 2018 (ISSN 1679-6225) Review article A review of the systematic biology of fossil and living bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha (Actinopterygii: Teleostei) Eric J. Hilton1 and Sébastien Lavoué2,3 The bony-tongue fishes, Osteoglossomorpha, have been the focus of a great deal of morphological, systematic, and evolutio- nary study, due in part to their basal position among extant teleostean fishes. This group includes the mooneyes (Hiodontidae), knifefishes (Notopteridae), the abu (Gymnarchidae), elephantfishes (Mormyridae), arawanas and pirarucu (Osteoglossidae), and the African butterfly fish (Pantodontidae). This morphologically heterogeneous group also has a long and diverse fossil record, including taxa from all continents and both freshwater and marine deposits.