Notes on Three Feldman Recordings by John Tilbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

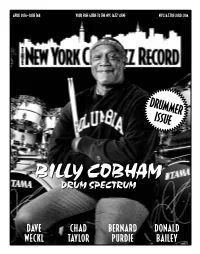

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Notes from the Underground: a Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music

Notes From The Underground: A Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music. Stephen Graham Goldsmiths College, University of London PhD 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: …………………………………………………. Date:…………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract The term ‗underground music‘, in my account, connects various forms of music-making that exist largely outside ‗mainstream‘ cultural discourse, such as Drone Metal, Free Improvisation, Power Electronics, and DIY Noise, amongst others. Its connotations of concealment and obscurity indicate what I argue to be the music‘s central tenets of cultural reclusion, political independence, and aesthetic experiment. In response to a lack of scholarly discussion of this music, my thesis provides a cultural, political, and aesthetic mapping of the underground, whose existence as a coherent entity is being both argued for and ‗mapped‘ here. Outlining the historical context, but focusing on the underground in the digital age, I use a wide range of interdisciplinary research methodologies , including primary interviews, musical analysis, and a critical engagement with various pertinent theoretical sources. In my account, the underground emerges as a marginal, ‗antermediated‘ cultural ‗scene‘ based both on the web and in large urban centres, the latter of whose concentration of resources facilitates the growth of various localised underground scenes. I explore the radical anti-capitalist politics of many underground figures, whilst also examining their financial ties to big business and the state(s). This contradiction is critically explored, with three conclusions being drawn. First, the underground is shown in Part II to be so marginal as to escape, in effect, post- Fordist capitalist subsumption. -

Understanding Michael Pisaro's Solo Piano Music Through Alain Badiou's Theory of the Event

Understanding Michael Pisaro’s Solo Piano Music through Alain Badiou’s theory of the Event Qais B A M S M Alghanem Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music April, 2019 Intellectual Property and Publication Statements The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Qais B A M S M Alghanem to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Qais B A M S M Alghanem. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank God Almighty for giving me the strength, knowledge, ability and opportunity to undertake this research study. I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisors, Professor Martin Iddon and Dr Michael Spencer, for always being supportive, patient, and helpful during my research years; without their contribution, this dissertation would not have been possible. Your tremendous advice on research and on my career has been priceless and allowed me to grow as a researcher. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and expertise and also for the trust you have given me over the years spent together. Next, I would like to thank the entire School of Music for making me feel so welcomed here in Leeds and for allowing me to use all their recording equipment. -

Soundweaving

Soundweaving Soundweaving: Writings on Improvisation Edited by Franziska Schroeder and Mícheál Ó hAodha Soundweaving: Writings on Improvisation, Edited by Franziska Schroeder and Mícheál Ó hAodha This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Franziska Schroeder, Mícheál Ó hAodha and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5344-5, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5344-6 1.1.1.1.1.1.1.14. With loving help from Imogene Newland, whom I thank immensely for supporting me in writing this extended, woven editorial. For the three most important boys: Pedro, Lukas and Max. Cover and book images by artist and tapestry weaver Ingrid Parker Heil: www.ingridparkerheil.co.uk 1.1.1.1.1.1.1.14. Weaving in progress. Artist and Tapestry Weaver Ingrid Parker Heil 1.1.1.1.1.1.1.14. CONTENTS Editorial ...................................................................................................... ix Performing Improvisation: Weaving Fabrics of Social Systems Franziska Schroeder Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Evan Parker Editorial -

PDF (Phd Commentary)

Durham E-Theses Commentary on the Portfolio of Compositions submitted for the degree of PhD in Music Composition, University of Durham by Mariam Rezaei, 2016 REZAEI, MARIAM How to cite: REZAEI, MARIAM (2017) Commentary on the Portfolio of Compositions submitted for the degree of PhD in Music Composition, University of Durham by Mariam Rezaei, 2016, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11968/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Commentary on the Portfolio of Compositions submitted for the degree of PhD in Music Composition University of Durham by Mariam Rezaei 2016 The copyright of this work rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without her prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Acknowledgements Special thanks to: Prof. Richard Rijnvos, supervisor, University of Durham Dr. -

2018 Building a Jazz Library

John Butcher By JOHN EYLES November 9, 2018 17,211 Views In the Building a Jazz Library article on Evan Parker, it says that seasoned Parker followers would describe him as the finest improvising saxophonist of his generation. Curiously, many of those same people would use exactly that phrase about John Butcher. The simple explanation for this apparent contradiction is that we are talking about two generations; Parker (born 1944) is a member of the "first generation of free improvisation" (along with Derek Bailey, Tony Oxley, John Stevens, Paul Rutherford, Barry Guy...) whereas Butcher (born 1954) is from the second generation (along with the similarly-aged Chris Burn, Phil Durrant, John Russell, Alan Wilkinson...) This is well illustrated by their discographies; Parker's first recording, Challenge (Eyemark), was released in 1966, while Butcher's first, Fonetiks (Bead)—a duo with Burn—came out in 1984. One reason for Butcher's first disc being released when he was slightly older is that after he had graduated with a B.Sc. in Physics from Surrey University he then studied for and obtained a doctorate in Theoretical Physics, before focussing on music. Although they are easy to tell apart, Butcher and Parker have a number of things in common; they both play tenor or soprano saxophone; they are the only saxophonists to have performed at Company Week, been a member of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and the London Improvisers Orchestra, and been a guest player with AMM. In addition, each of them (alone or with others) has been responsible for setting up two independent record labels to release their music, in Parker's case Incus (1970 to 1985) and Psi (2001 onwards), in Butcher's case Acta (1988 to 2001) and Weight of Wax (2004 onwards). -

Beckett, Music, Intermediality : John Tilbury's Worstward Ho

This is a repository copy of Beckett, music, intermediality : John Tilbury’s Worstward Ho. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/156756/ Version: Published Version Article: Laws, Catherine Ann orcid.org/0000-0002-3888-5989 (2020) Beckett, music, intermediality : John Tilbury’s Worstward Ho. Samuel Beckett Today/Aujourd’hui. pp. 116-128. ISSN 0927-3131 10.163/18757405-03201009 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd’hui 32 (2020) 116–128 brill.com/sbt Beckett, Music, Intermediality John Tilbury’s Worstward Ho Catherine Laws Department of Music, University of York, York, UK [email protected] Abstract The topic of ‘Beckett and music’ has gained considerable attention in recent years. In previous work I have argued that music in Beckett’s plays does not, as some have sug- gested, exist beyond or exceed the ambiguities of body, knowledge and subjectivity that are apparent in other aspects of his work, but rather that its use parallels and rein- forces these processes. -

Cornelius Cardew's Music for Moving Images

Cornelius Cardew’s Music for Moving Images: Some Preliminary Observations Clemens Gresser Some initial thoughts Whereas Cardew’s autonomous music (especially within a modernist or more experimental framework) has received some attention, his music for moving images and for radio has been little discussed to date.1 Such applied music seems to fit none of what could be seen as the four core areas of Cardew’s musical activity: 1. his modernist and avant-garde music (all his works before starting his early experiments with the Scratch Orchestra),2 2. his experimental and improvisational music (Scratch Orchestra, AMM), 3. his overtly political and tonal music (mainly songs, and often performed by PLM3 or the Songs for Our Society Group), or 4. his programmatic, indirectly political music (mostly piano music, such as Thälmann Variations).4 However, film and radio music might also feature (or can have traces of) any of the approaches found in other areas of his oeuvre. This research was supported by a three-month British Library Research Break (an annual scheme for BL staff). I am extremely grateful to my former colleagues in Music Collections, and particularly to Nicolas Bell and Sandra Tuppen, for allowing me to have access to uncatalogued material and generally answering all my questions; to Trish Hayes (BBC Written Archives), for helping me with BBC archival materials; and to Susan Reed for not interrupting my research work with queries relating to my previous library position. 1 John Tilbury, Cornelius Cardew (1936-1981): A Life Unfinished (Matching Tye, Essex, 2008), and Eddie Prévost (ed.), Cornelius Cardew: A Reader. -

Workshop Piece

AMM — historical precedence and theoretical precedents for the workshop AMM — historical and theoretical precedents for the workshop Informal ‘sound’ has a power over our emotional responses that formal ‘music’ does not, in that it acts subliminally rather than on a conscious cultural level. This is a possible definition of the area in which AMM is experimental. We are searching for sounds and for the responses that attach to them, rather than thinking them up, preparing them and producing them. The search is conducted in the medium of sound and the musician […] is at the heart of the experiment. 1 In 1999 I returned from a jazz festival and colloquium in Guelph, Canada and decided to set up and develop an improvisation workshop. This was to test, with others, if there was any continuing momentum and meaning in the kind of practice I had been part of, and subject to, within the ensemble AMM. The reputation of AMM might be enough to encourage the curious. Whether a significant amount would stay the course and help explore and develop a unique theory of improvisation was another matter. Only time would tell whether I would become more (or less) convinced of the efficacy of this practice. That was sixteen years ago. People are still coming. I have heard much music. I have learnt things. Made many friends. The following is a brief historical account of how I perceived AMM and my consequent thoughts about the theoretical basis of our shared experiences and how this has been extended and applied to a continuing cohort who share making music with others at our London workshop meetings. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Secret Gardeners: An Ethnography of Improvised Music in Berlin (2012-13) Tom Arthurs PhD Music The University of Edinburgh 2015 Abstract This thesis addresses the aesthetics, ideologies and practicalities of contemporary European Improvised Music-making - this term referring to the tradition that emerged from 1960s American jazz and free jazz, and that remains, arguably, one of today's most misunderstood and under-represented musical genres. Using a multidisciplinary approach drawing on Grounded Theory, Ethnography and Social Network Analysis, and bounded by Berlin's cosmopolitan local scene of 2012-13, I define Improvised Music as a field of differing-yet-interconnected practices, and show how musicians and listeners conceived of and differentiated between these sub-styles, as well as how they discovered and learned to appreciate such a hidden, ‘difficult’ and idiosyncratic artform. -

Free Improvisation As a Performance Technique: Group Creativity and Interpreting Graphic Scores

Free Improvisation as a Performance Technique: Group Creativity and Interpreting Graphic Scores Edward NEEMAN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree, The Juilliard School May 2014 2014 Edward Neeman This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. ABSTRACT The late 1950s and 1960s saw the formation of groups of musicians devoted to free improvisation. These groups deliberately excluded pre-existing musical idioms and focused on the nature of improvisation and the processes involved in spontaneously inventing music and interacting as a group. The history, recordings, and writings of this free improvisation movement is a valuable source for prospective improvisers and demonstrates that free improvisation can be a serious discipline capable of developing meaningful and powerful musical discourse. The techniques that its practitioners developed to stimulate innovation and to explore the interactive possibilities of group creativity can be used in many musical and interdisciplinary applications. The interpretation of indeterminate graphic scores is one such application. Classical musicians are particularly suited to meeting the interpretational challenges of these works, and an openness to improvisational approaches has the potential to reap great rewards in the realization of these neglected works. The work of Roman Haubenstock- Ramati, and particularly his Decisions (1959–1961) for unspecified sound sources, serves as an example through analysis of its structure and a critical evaluation of performative possibilities. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE The Australian-American pianist Edward Neeman has won first prizes in the Rodrigo and Carlet international piano competitions and has performed with orchestras including the Prague Philharmonic, the Madrid Philharmonic, the Sydney Symphony, Melbourne Symphony, West Australia Symphony, Canberra Symphony, and The Queensland Orchestra.