University of Huddersfield Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

A Clear Apparance

A Clear Apparence 1 People in the UK whose music I like at the moment - (a personal view) by Tim Parkinson I like this quote from Feldman which I found in Michael Nyman's Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond; Anybody who was around in the early fifties with the painters saw that these men had started to explore their own sensibilities, their own plastic language...with that complete independence from other art, that complete inner security to work with what was unknown to them. To me, this characterises the music I'm experiencing by various composers I know working in Britain at the moment. Independence of mind. Independence from schools or academies. And certainly an inner security to be individual, a confidence to pursue one's own interests, follow one's own nose. I donʼt like categories. Iʼm not happy to call this music anything. Any category breaks down under closer scrutiny. Post-Cage? Experimental? Post-experimental? Applies more to some than others. Ultimately I prefer to leave that to someone else. No name seems all-encompassing and satisfying. So Iʼm going to describe the work of six composers in Britain at the moment whose music I like. To me itʼs just that: music that I like. And why I like it is a question for self-analysis, rather than joining the stylistic or aesthetic dots. And only six because itʼs impossible to be comprehensive. How can I be? Thereʼs so much good music out there, and of course there are always things I donʼt know. So this is a personal view. -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2019). The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1). In: Dodd, R. (Ed.), Writing to Louis Andriessen: Commentaries on life in music. (pp. 83-101). Eindhoven, the Netherlands: Lecturis. ISBN 9789462263079 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/22291/ Link to published version: Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1) Ian Pace Introduction Assumptions of over-arching unity amongst composers and compositions solely on the basis of common nationality/region are extremely problematic in the modern era, with great facility of travel and communications. Arguments can be made on the bases of shared cultural experiences, including language and education, but these need to be tested rather than simply assumed. Yet there is an extensive tradition in particular of histories of music from the United States which assume such music constitutes a body of work separable from other concurrent music, or at least will benefit from such isolation, because of its supposed unique properties. -

Booklet Tilbury.Qxd:Booklet DROUET

John Tilbury - Piano John Tilbury has given concerts and broadcasts of new music, including first performances, in many countries around the world. His solo recordings include Cage's Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano, from the seventies, and more recently the music of Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton, Christian Wolff and the complete solo piano works of Morton Feldman. He is also well known as an improvising musician, through his membership of AMM, one of the most distinguished and influential free improvisation groups to have emerged in the sixties. In preparation for a talk I was to give on Feldman and Skempton, I wrote down the following notes as a kind of aide-mémoire. John Tilbury 1996 On Softness Softness – also length, and brevity. But 'not for its own sake’. ‘Virtuosity of restraint’ (Skempton). Alice (in Wonderland) had to accustom herself to new dimensions. Soft 'as possible'. Relative. Degree and quality of softness depends on the acoustical and the psychological. Awareness of this dynamic quality within softness creates an extraordinary variety. Softness draws the audience into the music - it encourages attentiveness and alertness. It also demands a ‘transcendental’ listening in its search for a revelatory experience. Softness heightens consciousness; also enhances the consciousness, for example, of the idiosyncrasies of the instrument at which one sits. On the unintended This respect for the unintended embodies the notion for the interpreter of nowness, of uniqueness. Accidentalness is an active component, to be convincingly contextualized. The music responds to the contingencies of venue, of temperature, etc. etc. This, together with an emphasis on the sensual and physical qualities of the art of performance, creates an indivisibility of musician and instrument and at best of music and audience; an at one-ness. -

Jems: Journal of Experimental Music Studies - Reprint Series

12 April 2012 Jems: Journal of Experimental Music Studies - Reprint Series The Music of Howard Skempton Michael Parsons Originally published in Contact no. 21 (Autumn 1980), pp. 12-16. Reprinted with the kind permission of the author. Since 1967, when he first moved to London to study privately with Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton has pursued an even and consistent course in his music, focusing and refining his central concerns. His concentration on the quality of sound and his economy of means are already clearly evident in early works such as A Humming Song (1967), Snowpiece and September Song (both 1968) and Piano Piece 1969.1 These piano pieces are predominantly static and without development, presenting in chance-determined sequence a limited number of carefully pre-selected notes or chords. The usual playing direction is ‘very slowly and quietly’, and there is little sense of forward momentum; each individual sound is allowed to resonate freely, and successive notes or chords are related to each other only by juxtaposition. There is a clear relationship with the earlier music of Feldman, but in Skempton’s pieces the means are even more economical. A Humming Song was actually written in April 1967 when Skempton was 19, a few months before he began studying with Cardew. It is for a pianist who is asked also to sustain certain notes by humming; this, incidentally, requires considerable control and relaxation and disproves the false notion that Skempton’s music is always technically easy to perform. This composition is worth describing in some detail, since it uses methods which can be found in many of Skempton’s other works. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988)

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Potter, Keith. 1977. ‘New Music Diary’. Contact, 16. pp.29-33. ISSN 0308-5066. ! NEW MUSIC DIARY work) with being Musical Director at the Birmingham Arts Laboratory. This, the sole survivor of the 60s Lab scene, has, KEITH POTIER incidentally, recently started music publishing in a small way with Emmerson's Variations. Three months (November 1976 to the beginning of February 1977) to cover in this issue, as opposed to only just over one month in Monday November 16 Contact 15, so my comments will be somewhat briefer, even though the density of events attended was quite a lot lower for this The first of two concerts entitled 'Boulez at The Round House' put period. on by the BBC. In spite of recent, and not so recent, flops in So many of the 'established' ('establishment'?) new music audience attendance at this BBC new music series, there was quite concerts attract so many of the same type of audience(or rather, so a good crowd for this one, at any rate (the other, on November 29,1 many of the so few) that one comes to accept this state of affairs as didn't attend, nor did I catch its broadcast later: it included the perfectly natural. Surely it shouldn't be? No wonder that many of British premiere of the young Italian Giuseppe Sinopoli's Drei the more experimental musicians have for some years now been Stiicke BUS Souvenirs ale Memoire and Elliott Carter's A Mirror on seeking venues other than, for example, the South Bank and even which to Dwell, as well as Schoenberg's Serenade, Op.24). -

Notes on Three Feldman Recordings by John Tilbury

Notes on Three Feldman Recordings by John Tilbury Triadic Memories (with, Howard Skempton Notti Stellate a Vagli) [Atopos CD ATP 012/013, 2008] In preparation for a talk I was to give on Feldman and Skempton, I wrote down the following notes as a kind of aide-memoire. On Softness Softness – also length, and brevity. But ‘not for its own sake’. ‘Virtuosity of restraint’ (Skempton). Alice (in Wonderland) had to accustom herself to new dimensions. Soft ‘as possible’. Relative. Degree and quality of softness depends on the acoustical and the psychological. Awareness of this dynamic quality within softness creates an extraordinary variety. Softness draws the audience into the music - it encourages attentiveness and alertness. It also demands a ‘transcendental’ listening in its search for a revelatory experience. Softness heightens consciousness; also enhances the consciousness, for example, of the idiosyncrasies of the instrument at which one sits. On the unintended This respect for the unintended embodies the notion for the interpreter of nowness, of uniqueness. Accidentalness is an active component, to be convincingly contextualized. The music responds to the contingencies of venue, of temperature, etc. etc. This, together with an emphasis on the sensual and physical qualities of the art of performance, creates an indivisibility of musician and instrument and at best of music and audience; an at-oneness. Accidentalness need not cause embarrassment; rather the accidental (unintended sounds) is to be enjoyed, nourished, sometimes indulged. The ‘accidental’ is a corollary of the extreme softness which Feldman demands and which necessarily involves risk. The player is playing on the edge, on the frontier between sound and no sound. -

Section I - Overview

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Masterworks Subject: Terry Riley Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 SECTION II – PROFILE & CONTEXT..................................................................................................3 ARTIST PROFILE CONTEXT: THE BIG PICTURE.............................................................................................................4 SECTION III – RESOURCES .................................................................................................................6 TEXTS & PERIODICALS AUDIO RECORDINGS WEB SITES VIDEOS SECTION IV – BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS..............................................................................................9 SECTION III – VOCABULARY.......................................................................................................... 10 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 12 Composer Terry Riley reflects on a long, successful career. Still image from SPARK story June 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES Masterworks Individual and group research Individual and group exercises SUBJECT Written research materials Terry Riley Group oral discussion, review and analysis GRADE RANGES K-12, Post-Secondary EQUIPMENT NEEDED TV & VCR with SPARK story “Masterworks,” about CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS Terry Riley and Kronos Quartet Music -

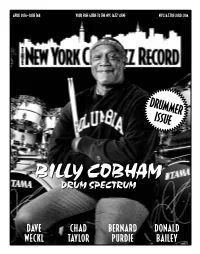

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation West, Peter and Evans, Peter. 1971. ‘Interview with Christopher Hobbs’. Contact, 3. pp. 17-23. ISSN 0308-5066. ! - 17 - INTER.V.Thv\1 vi1TH CHR.ISTOPHER. HOBBS Christopher Hobts -a composer, member of P.T.O., ex-member of AMM., editor of the Experimental Music Catalogue· - was interTiewed recently by Peter Wes.t and Peter EVans. · ·· Could we sta,rt off by asking you something about your musical education? I studied bassoon and piano at Trinity College of Music and composition and percussion at the Royal Academy. Before that I had been l§o grammar school in Northwood. · And you studied the usual kind of music there? Yes. Did you become less certain of: the capabilities of conventional music while you were still at school? It wasn't a matter of becoming less certain of it because we were lucky in having amusic master enlightened enough to play us records of Cage and Boulez as well as Beethoven anQ. .Holst - and it became immediately apparent that i preferred the of Cage and Boulez.· So you could say that I took natlirally to the newer type of music; though I had to study older music to pass the exam- inations, of course. Do you think these examinations have any relevance? None I didn 1 t actudlly need to,pass any to go to the Oollege and I didn't take any >ihile r was at · the qollege •••• That means you're totally unqualified? Yes. Then do you think that s.tudies in traditional harmony and counterpoint are totally useless? I've never found a use for them.