Tactile Paths: on and Through Notation for Improvisers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CNMAT Notes.Indd

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Saturday, February 11, 2006, 8 pm Hertz Hall CNMAT Presents: Mark Dresser, Myra Melford, Bob Ostertag, David Wessel Th is presentation is made possible, in part, by the generous support of Liz and Greg Lutz. Cal Performances thanks our Centennial Season Sponsor, Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 29 ABOUT THE ARTISTS ABOUT THE ARTISTS Jazziz magazine noted, “Th e confi dence to go included the Kronos Quartet, avant-gardists so far into uncharted territory and the ability John Zorn and Fred Frith, heavy metal star to carry listeners along—then bring them Mike Patton, jazz great Anthony Braxton, back—attest to Melford’s vision.” dyke punk rocker Lynn Breedlove, drag diva Myra Melford is currently Assistant Justin Bond, fi lmmaker Pierre Hébert and Professor of Improvisation and Jazz in the others. He is rumored to have connections Department of Music at the University of to the shadowy media guerrilla group Th e California, Berkeley. Yes Men. Bob Ostertag recently joined the Department of Technocultural Studies at the University of California, Davis, where he is an Associate Professor. Myra Melford (piano and electronics) is “the genuine article, the most gifted pianist/ Mark Dresser has been composing and composer to emerge from jazz since Anthony performing solo contrabass and ensemble Davis,” according to critic Francis Davis. A music professionally throughout North composer and bandleader with a “commitment Composer, performer, instrument builder, America, Europe and the Far East since to refreshing, often surprising uses of melody, journalist, activist, historian, kayak instruc- 1972. He has recorded more than 100 CDs harmony and ensemble playing,” according to tor—Bob Ostertag’s work cannot easily be with some of the strongest personalities in NPR, Melford currently leads or co-leads four summarized or pigeon-holed. -

Music, Politics, People, and Machines

Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 6, No 2 (2010) Book Review Creative Life: Music, Politics, People, and Machines Bob Ostertag Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2009 ISBN-10: 025207646X ISBN-13: 978-0252076466 194 pages Reviewed by Rob Wallace The title of Bob Ostertag’s third book is more accurately rendered as Creative Life Music Politics People and Machines—a continuous stream of concepts connected precariously only through Ostertag himself. The key term is “creative,” along with the equally important “people.” For while Ostertag’s book is on the one hand a collection of essays touching on various aspects of his own biography and artwork, it is also a series of engaging and at times very moving portraits of his contemporaries. Profiling such figures as Anthony Braxton, David Wojnarowicz, Jim Magee, “Maria,” Aleksandra Kostic, and Justin Bond, Creative Life is a story of many creative “lives” that in some way have intersected with the creative life of the protagonist, Ostertag. Some of these lives may be familiar to readers, some not so familiar, and that latter fact is one of the book’s greatest strengths: as an advocate of artists in particular and interesting people in general, Ostertag’s narrative makes the individuals he meets seem intriguing and potentially life-changing, regardless of their level of “fame” in their respective worlds. The information about Texas-based artist Jim Magee, for example, is reason enough to read the book (and if you are unfamiliar with Magee, as I was, take my word for it and read Ostertag’s profile). -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Variations #6

Curatorial > VARIATIONS VARIATIONS #6 With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from The Library different points of view organised in curatorial series. We encounter the establishment of sound libraries, collections explicitly curated 'Variation' is the formal term for a musical composition based for further use: sound objects presented as authorless, unfinished ingredients. on a previous musical work, and many of those traditional Though some libraries contain newly commissioned generic sounds, specifically methods (changing the key, meter, rhythm, harmonies or designed for maximum flexibility, the most widely used sounds are often sourced tempi of a piece) are used in much the same manner today from commercial recordings, freed from their original context to propagate across by sampling musicians. But the practice of sampling is more dozens to hundreds of songs. From presets for digital samplers to data CD-ROMs than a simple modernization or expansion of the number of to hip-hop battle records, sounds increasingly detach from their sources, used options available to those who seek their inspiration in the less as references to any original moment, and more as objects in a continuous refinement of previous composition. The history of this music public domain. traces nearly as far back as the advent of recording, and its As hip-hop undergoes a conservative retrenchment in the wake of the early emergence and development mirrors the increasingly self- nineties sampling lawsuits, a widening variety of composers and groups expand conscious relationship of society to its experience of music. the practice of appropriative audio collage as a formal discipline. -

A Zeitgeist Films Release Theatrical Booking Contact: Festival Booking and Publicity Contact

Theatrical Booking Festival Booking and Contact: Publicity Contact: Clemence Taillandier / Zeitgeist Films Nadja Tennstedt / Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 x18 212-274-1989 x15 [email protected] [email protected] a zeitgeist films release act of god a film by Jennifer Baichwal Is being hit by lightning a random natural occurrence or a predestined event? Accidents, chance, fate and the elusive quest to make sense out of tragedy underpin director Jennifer Baichwal’s (Manufactured Landscapes) captivating new work, an elegant cinematic meditation on the metaphysical effects of being struck by lightning. To explore these profound questions, Baichwal sought out riveting personal stories from around the world—from a former CIA assassin and a French storm chas- er, to writer Paul Auster and improvisational musician Fred Frith. The philosophical anchor of the film, Auster was caught in a terrifying and deadly storm as a teenager, and it has deeply affected both his life and art: “It opened up a whole realm of speculation that I’ve continued to live with ever since.” In his doctor brother’s laboratory, Frith experiments with his guitar to demonstrate the ubiquity of electricity in our bodies and the universe. Visually dazzling and aurally seductive, Act of God singularly captures the harsh beauty of the skies and the lives of those who have been forever touched by their fury. DIRECTOR’S NOTES I studied philosophy and theology before turning to documentary and, in some ways, the questions I was drawn to then are the ones I still grapple with now, although in a different context. Two of these, which specifically inform this film, are the relationship between meaning and randomness and the classical problem of evil. -

Reprint from Artistic Experimentation in Music - ISBN 978 94 6270 013 0 - © Leuven University Press, 2014 ARTISTIC EXPERIMENTATION in MUSIC

Reprint from Artistic Experimentation in Music - ISBN 978 94 6270 013 0 - © Leuven University Press, 2014 ARTISTIC EXPERIMENTATION IN MUSIC: AN ANTHOLOGY Artistic Experimentation in Music: an Anthology Edited by Darla Crispin and Bob Gilmore Leuven University Press Table of Contents 9 Introduction Darla Crispin and Bob Gilmore Section I Towards an Understanding of Experimentation in Artistic Practice 23 Five Maps of the Experimental World Bob Gilmore 31 The Exposition of Practice as Research as Experimental Systems Michael Schwab 41 Epistemic Complexity and Experimental Systems in Music Performance Paulo De Assis 55 Experimental Art as Research Godfried-Willem Raes 61 Tiny Moments of Experimentation: Kairos in the Liminal Space of Performance Kathleen Coessens 69 The Web of Artistic Practice: A Background for Experimentation Kathleen Coessens 83 Towards an Ethical-Political Role for Artistic Research Marcel Cobussen 91 A New Path to Music: Experimental Exploration and Expression of an Aesthetic Universe Bart Vanhecke 105 From Experimentation to Construction Richard Barrett 111 Artistic Research and Experimental Systems: The Rheinberger Questionnaire and Study Day: A Report Michael Schwab 5 Table of Contents Section II The Role of the Body: Tacit and Creative Dimensions of Artistic Experimentation 129 Embodiment and Gesture in Performance: Practice-Based Perspectives Catherine Laws 141 Order Matters A Thought on How to Practise Mieko Kanno 147 Association-Based Experimentation as an Artistic Research Method Valentin Gloor 151 Association -

Sine Waves and Simple Acoustic Phenomena in Experimental Music - with Special Reference to the Work of La Monte Young and Alvin Lucier

Sine Waves and Simple Acoustic Phenomena in Experimental Music - with Special Reference to the Work of La Monte Young and Alvin Lucier Peter John Blamey Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my principal supervisor Dr Chris Fleming for his generosity, guidance, good humour and invaluable assistance in researching and writing this thesis (and also for his willingness to participate in productive digressions on just about any subject). I would also like to thank the other members of my supervisory panel - Dr Caleb Kelly and Professor Julian Knowles - for all of their encouragement and advice. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .......................................................... (Signature) Table of Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................iii Introduction: Simple sounds, simple shapes, complex notions.............................1 Signs of sines....................................................................................................................4 Acoustics, aesthetics, and transduction........................................................................6 The acoustic and the auditory......................................................................................10 -

Surprising Connections in Extended Just Intonation Investigations and Reflections on Tonal Change

Universität der Künste Berlin Studio für Intonationsforschung und mikrotonale Komposition MA Komposition Wintersemester 2020–21 Masterarbeit Gutachter: Marc Sabat Zweitgutachterin: Ariane Jeßulat Surprising Connections in Extended Just Intonation Investigations and reflections on tonal change vorgelegt von Thomas Nicholson 369595 Zähringerstraße 29 10707 Berlin [email protected] www.thomasnicholson.ca 0172-9219-501 Berlin, den 24.1.2021 Surprising Connections in Extended Just Intonation Investigations and reflections on tonal change Thomas Nicholson Bachelor of Music in Composition and Theory, University of Victoria, 2017 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Department of Composition January 24, 2021 First Supervisor: Marc Sabat Second Supervisor: Prof Dr Ariane Jeßulat © 2021 Thomas Nicholson Universität der Künste Berlin 1 Abstract This essay documents some initial speculations regarding how harmonies (might) evolve in extended just intonation, connecting back to various practices from two perspectives that have been influential to my work. The first perspective, which is the primary investigation, concerns itself with an intervallic conception of just intonation, centring around Harry Partch’s technique of Otonalities and Utonalities interacting through Tonality Flux: close contrapuntal proximities bridging microtonal chordal structures. An analysis of Partch’s 1943 composition Dark Brother, one of his earliest compositions to use this technique extensively, is proposed, contextualised within his 43-tone “Monophonic” system and greater aesthetic interests. This is followed by further approaches to just intonation composition from the perspective of the extended harmonic series and spectral interaction in acoustic sounds. Recent works and practices from composers La Monte Young, Éliane Radigue, Ellen Fullman, and Catherine Lamb are considered, with a focus on the shifting modalities and neighbouring partials in Lamb’s string quartet divisio spiralis (2019). -

Human Bodies, Computer Music Author(S): Bob Ostertag Source: Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 12, Pleasure, (2002), Pp. 11-14 Publis

Human Bodies, Computer Music Author(s): Bob Ostertag Source: Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 12, Pleasure, (2002), pp. 11-14 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1513343 Accessed: 23/07/2008 16:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Human Bodies, Computer Music ABSTRACT The authorconsiders the absenceof theartist's body in electronicmusic, a missing BobOstertag elementthat he finds crucial to thesuccess of anywork of art. Inreviewing the historical developmentof electronic music frommusique concrete to analogand then digital synthe- sizers,the author finds that the attainmentof increased control iierre Hebert, a frequent collaborator of mine, use outside of research institutions. -

Notes on Three Feldman Recordings by John Tilbury

Notes on Three Feldman Recordings by John Tilbury Triadic Memories (with, Howard Skempton Notti Stellate a Vagli) [Atopos CD ATP 012/013, 2008] In preparation for a talk I was to give on Feldman and Skempton, I wrote down the following notes as a kind of aide-memoire. On Softness Softness – also length, and brevity. But ‘not for its own sake’. ‘Virtuosity of restraint’ (Skempton). Alice (in Wonderland) had to accustom herself to new dimensions. Soft ‘as possible’. Relative. Degree and quality of softness depends on the acoustical and the psychological. Awareness of this dynamic quality within softness creates an extraordinary variety. Softness draws the audience into the music - it encourages attentiveness and alertness. It also demands a ‘transcendental’ listening in its search for a revelatory experience. Softness heightens consciousness; also enhances the consciousness, for example, of the idiosyncrasies of the instrument at which one sits. On the unintended This respect for the unintended embodies the notion for the interpreter of nowness, of uniqueness. Accidentalness is an active component, to be convincingly contextualized. The music responds to the contingencies of venue, of temperature, etc. etc. This, together with an emphasis on the sensual and physical qualities of the art of performance, creates an indivisibility of musician and instrument and at best of music and audience; an at-oneness. Accidentalness need not cause embarrassment; rather the accidental (unintended sounds) is to be enjoyed, nourished, sometimes indulged. The ‘accidental’ is a corollary of the extreme softness which Feldman demands and which necessarily involves risk. The player is playing on the edge, on the frontier between sound and no sound. -

Interweavings.Towards a New View of The

1 INTERWEAVINGS Towards a new view of the relation between composition and improvisation by Nina Polaschegg Translated by Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen*) This article was first published as "Verflechtungen. Zur Neubestimmung des Verhältnisses von Komposition und Improvisation" in MusikTexte 114, August 2007. Our (German) official view of music history since 1945 is still centred on two paradigms which were developed within the Darmstadt Summer Courses. These are serialism on one hand including the reaction against it from the side of Cageians - and aleatorics and other strategies for opening up the musical work on the other. In composed music of today, aleatorics play only an insignificant role, just like strict serialism. Open structures in music works are exceptions within contemporary composition. Thus, the quasi official view of music concerns itself with positions stemming from the origin of New Music after 1950. They admittedly implied a radical thinking through of principal possibilities for employing a new view of the musical work. Consequently they also appeared necessary and revolutionary, but they have remained without a real succession. When employing this view, the dominant view of the developing new contemporary music represses or marginalises the fact that aleatorics and open work structures were only a small part of a diverse movement against the traditional notion of music, musician and musical work. And, remarkably, exactly these repressed dimensions of this reaction have lived on and unfolded a strong influence precisely in recent years. Improvisation plays a central role in these new views – and this is the case inside as well as outside the traditional context of New Music. -

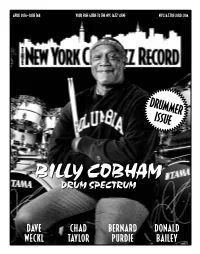

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step.