Art Pepper's Not the Same by John Tynan 07/30/1964 Downbeat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musica Jazz Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA JAZZ AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE AA.VV. Blues for Dummies MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. \The \\metronomes MSJ/CD MET AA.VV. Beat & Be Bop MSJ/CD BEA AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Victor Jazz History vol. 13 MSJ/CD VIC AA.VV. Blue'60s MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. 8 Bold Souls MSJ/CD EIG AA.VV. Original Mambo Kings (The) MSJ/CD MAM AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 1 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. New Orleans MSJ/CD NEW AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 2 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. \Le \\grandi trombe del Jazz MSJ/CD GRA AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion two (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe III: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI AA.VV. Celebrating the music of Weather Report MSJ/CD CEL AA.VV. Night and Day : The Cole Porter Songbook MSJ/CD NIG AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe II: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball Adderley MSJ/CD ADD Aires Tango Origenes [CD] MSJ/CD AIR Al Caiola Serenade In Blue MSJ/CD ALC Allison, Mose Jazz Profile MSJ/CD ALL Allison, Mose Greatest Hits MSJ/CD ALL Allyson, Karrin Footprints MSJ/CD ALL Anikulapo Kuti, Fela Teacher dont't teach me nonsense MSJ/CD ANI Armstrong, Louis Louis In New York MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong live in Europe MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Satchmo MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis -

Art Pepper a Taste of Pepper Mp3, Flac, Wma

Art Pepper A Taste Of Pepper mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: A Taste Of Pepper Country: Europe Released: 2010 Style: Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1175 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1614 mb WMA version RAR size: 1715 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 650 Other Formats: VOC WMA AC3 AAC MIDI AIFF MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Art Pepper Meets The Rhythm Section ( 1957 ) You'd Be So Nice To Come Home To 1-1 5:29 Composed By – C. Porter* Red Pepper Blues 1-2 3:41 Composed By – R. Garland* Imagination 1-3 5:55 Composed By – J. Van Heusen And J. Burke* Waltz Me Blues 1-4 3:00 Composed By – A. Pepper*, P. Chambers* Straight Life 1-5 4:02 Composed By – A. Pepper* Jazz Me Blues 1-6 4:50 Composed By – T. Delaney* Tin Tin Deo 1-7 7:45 Composed By – C. Pozo*, G. Fuller* Star Eyes 1-8 5:16 Composed By – D. Raye*, G. DePaul* Birks Works 1-9 4:20 Composed By – D. Gillespie* Mucho Calor ( 1958 ) Mucho Calor 2-1 6:55 Arranged By – Bill HolmanComposed By – B. Holman* Autumn Leaves 2-2 Arranged By – Benny CarterComposed By – G. Parsons*, J. Prévert*, J. 3:07 Mercer*, J. Kosma* Mambo De La Pinta 2-3 5:30 Arranged By – Art PepperComposed By – A. Pepper* I'll Remember April 2-4 2:22 Arranged By – Art PepperComposed By – D. Raye*, G. DePaul*, P. Johnston* Vaya Hombre Vaya 2-5 3:23 Arranged By – Bill HolmanComposed By – B. Holman* I Love You 2-6 5:49 Arranged By – Bill HolmanComposed By – C. -

Scholarships…A Mission, Not an Option! by Don Bestor, Jr

Winter, 2012 The Fort Pierce Jazz & Blues Society Newsletter Volume XVI MISSION: To promote the growth, appreciation and performance of Jazz & Blues – great American music art forms – through scholarships, workshops, clinics, weekly jazz jams and community outreach programs. Scholarships…a mission, not an option! By Don Bestor, Jr. prospective scholarship applicants to basis requires an extra effort to affect President get involved. Our very well put together positive results. This is just part of what A while ago, one scholarship program, I might add, is goes on “behind the scenes.” None of of our regular fans headed by one of our Board members, this deters our determination to get on approached me Mr. Al Hager, an award-winning educa- with what we’re here to accomplish. and asked if we were still sponsor- tor for more than 25 years! Please allow me to yell the answer ing students on their way to college in To manage an organization like the to the question of us being pro-active in the form of scholarships. That ques- Jazz and Blues Society of Fort Pierce the scholarship program: "YES!" We tion took me by surprise because that is an honor and it is something that remain committed to providing scholar- is why many of us dedicate our time I’m very respectful of. As you may or ships to those high school seniors who to this organization. The Society ac- may not know, many things happen, qualify for our program and we are so tively pursues student applicants with transpire, pop-up and sometimes it can very proud to be able to do that! We a monthly letter to every band director happen every day. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BILL HOLMAN NEA Jazz Master (2010) Interviewee: Bill Holman (May 21, 1927 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: February 18-19, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 84 pp. Brown: Today is Thursday, February 18th, 2010, and this is the Smithsonian Institution National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Oral History Program interview with Bill Holman in his house in Los Angeles, California. Good afternoon, Bill, accompanied by his wife, Nancy. This interview is conducted by Anthony Brown with Ken Kimery. Bill, if we could start with you stating your full name, your birth date, and where you were born. Holman: My full name is Willis Leonard Holman. I was born in Olive, California, May 21st, 1927. Brown: Where exactly is Olive, California? Holman: Strange you should ask [laughs]. Now it‟s a part of Orange, California. You may not know where Orange is either. Orange is near Santa Ana, which is the county seat of Orange County, California. I don‟t know if Olive was a part of Orange at the time, or whether Orange has just grown up around it, or what. But it‟s located in the city of Orange, although I think it‟s a separate municipality. Anyway, it was a really small town. I always say there was a couple of orange-packing houses and a railroad spur. Probably more than that, but not a whole lot. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Legends of West Brochure

JAZZ AID P U.S. POSTAGE presents WEST NONPROFIT ORG. PERMIT NO. 1260 LONG BEACH, CA. COAST 3 LEGENDS OF THE WEST 17 Concerts 8 Panel Discussions A Four Day 5 Film Showings Jazz Festival September 29 ~ October 2, 2005 8-0038 Four Points Sheraton-LAX NG BEACH, CA 9080 CA BEACH, NG .O. BOX 8038.O. BOX LO THE ANGELES LOS JAZZ INSTITUTE P WAY OUT WEST 1957 BY WILLIAM CLAXTON lajazzinstitute.org Bud Shank | Johnny Mandel | Chico Hamilton Quintet | Paul Horn BONUS EVENT Frank Morgan | Buddy Collette | Med Flory | Howard Rumsey In our continuing effort to pay tribute to the Lennie Niehaus | Jack Costanzo | Dave Pell Octet | Herb Geller brilliant artists who have Allyn Ferguson’s Chamber Jazz Sextet | Anthony Ortega | Bill Trujillo been significant figures of the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, FEATURING Claude Williamson | Chuck Flores | John Pisano | Fred Katz we are pleased to announce Jazz West Coast 3- ABOUT THE Legends of the West. Festival Los Angeles Legends of the West is a musical celebration of Facts Jazz Institute both the musicians and The Los Angeles Jazz Institute houses the behind the scenes people Dates and maintains one of the largest whose innovative explorations SEPTEMBER 29-OCTOBER 2, 2005 jazz archives in the world.All styles created a unique jazz scene and eras are represented with a here on the west coast. Place special emphasis on the preservation The Four Points Sheraton at LAX and documentation of jazz in southern In addition to 17 concerts, 9750 Airport Blvd., California. Many artists personal there will also be film showings, Los Angeles, CA 90045 collections are being preserved at panel discussions, photo exhibits The special convention rate is the Institute including the archives and special presentations where $82 and $92 per night. -

Los Angeles: Recorded Magic (1945-1960)

Los Angeles: Recorded Magic (1945-1960) Essential Questions How did advances in technology impact jazz? How did Los Angeles (LA) become a segregated city? How did Los Angeles (LA) become a city of recorded jazz? What is West Coast bop? How does it reflect the black jazz scene in segregated LA? What is West Coast jazz? How is it a product of postwar Southern California? How does the music and literature of Los Angeles reflect its history and culture? How do you listen to jazz? The importance of listening Obtaining a jazz vocabulary Understanding and appreciating major movements in jazz Understanding and appreciating the life and sounds of jazz innovators Historical context of jazz Objectives: 1. Determine how advances in technology impacted jazz and the recording industry. 2. Rank the local, state and federal policies that contributed to the segregation of Los Angeles. 3. Explain how the music and of Los Angeles reflected its segregated population. 4. Analyze West Coast jazz and bop in historical context. Historical Context: Postwar Los Angeles (Marcie Hutchinson) Based on Why Jazz Happened by Marc Myers (social history of jazz) Introduction Profound impact of technology on the history of jazz Radio, records, the phonograph, the jukebox, film Music more accessible, more convenient, pleasing to the ear Postwar Period Jazz transformed from dance music to a sociopolitical movement Major jazz styles: bebop, jazz-classical, cool, West Coast jazz, hard bop, jazz-gospel, spiritual jazz, jazz- pop, avant-garde jazz and jazz-rock fusion Jazz reshaped from 1945-1972 Grip of 3 major record companies (Victor, Columbia, Decca) weakened by labor actions Increased competition from new labels Jazz musicians gain greater creative independence due to competition. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement. -

WAY out WEST Brochure

P.O. Box 8038 Long Beach, CA 90808-0038 WAY OUT WEST The Los Angeles Jazz Institute presents WAY OUT WEST a celebration of big bands on the west coast past and present THE CROWNE PLAZA REDONDO BEACH & MARINA HOTEL OCTOBER 5-8, 2000 SCHEDULED TO APPEAR MAYNARD B FERGUSON IG BOP ’S WAY OUT NOUVEAU WILSON ’m very pleased to announce a four day jazz festival set to take ERALD I HE G place October 5th through the 8th at the Crowne Plaza Hotel in T WEST ORCHESTRA Redondo Beach, a very popular venue for many of our previous events. T The focus this year is “Way Out West”-Big Bands on the West Coast- HE BILL HOLMAN Past and Present. ORCHESTRA Following in the footsteps of “Back To Balboa”, “Early Autumn”, “Blowin’ Up A Storm”, “Modern Sounds” and “Jazz West Coast I & II”, GIBBS’ “Way Out West” will feature concerts, panel discussions, film showings, TERRY THE BAND vendors offering compact discs, records, memorabilia— and much more! DREAM This incredible gathering includes many of the most outstanding THE CLAYTON big bands in the world, all featuring an amazing array of jazz soloists. -HAMILTON JAZZ ORCHESTRA Full registration is $300.00 which includes admission to all events or, you can purchase individual event tickets which range from $10-$25. DATES October 5-8, 2000 For the first time, full registrants will have reserved seating for all THE BOB FLORENCE concerts. Seats will be assigned in the order registrations are received. LIMITED EDITION PLACE The Crowne Plaza Redondo Beach & Marina Hotel SEND YOUR CHECK OR MONEY ORDER TO: 300 North Harbor Drive THE PHIL NORMAN Redondo Beach, CA 90277 The Los Angeles Jazz Institute TENTET P.O. -

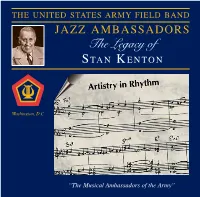

The Legacy of S Ta N K E N to N

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND JAZZ AMBASSADORS The Legacy of S TA N K ENTON Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Jazz Ambassadors is the Concerts, school assemblies, clinics, T United States Army’s premier music festivals, and radio and televi- touring jazz orchestra. As a component sion appearances are all part of the Jazz of The United States Army Field Band Ambassadors’ yearly schedule. of Washington, D.C., this internation- Many of the members are also com- ally acclaimed organization travels thou- posers and arrangers whose writing helps sands of miles each year to present jazz, create the band’s unique sound. Concert America’s national treasure, to enthusi- repertoire includes big band swing, be- astic audiences throughout the world. bop, contemporary jazz, popular tunes, The band has performed in all fifty and dixieland. states, Canada, Mexico, Europe, Ja- Whether performing in the United pan, and India. Notable performances States or representing our country over- include appearances at the Montreux, seas, the band entertains audiences of all Brussels, North Sea, Toronto, and New- ages and backgrounds by presenting the port jazz festivals. American art form, jazz. The Legacy of Stan Kenton About this recording The Jazz Ambassadors of The United States Army Field Band presents the first in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contri- butions to big band jazz. Designed primarily as educational resources, these record- ings are a means for young musicians to know and appreciate the best of the music and musicians of previous generations, and to understand the stylistic developments leading to today’s litera- ture in ensemble music. -

This Is a Pirated Album, Released in Spain: Art Pepper Live at the Jazz Showcase in Chicago 1977

This is a pirated album, released in Spain: Art Pepper live at the jazz showcase in Chicago 1977. With Willie Pickens, Steve Rodby, Wilbur Campbell. While I can’t afford to re-issue it here as a cd, I figure it’s worth releasing on the basis of some lovely performances. This was recorded in ‘77 in the middle of Art’s East Coast Tour, sponsored by John Snyder. The tour ended in NYC, when the earthshaking Vanguard recordings were made with George Cables, George Mraz, and Elvin Jones. In the meantime, Art played here and there with pickup bands. This one one of them. As I recall, Art didn’t get along with Willie Pickens at all. I don’t know why, I just remember Art grumbling about him. And when I listen to the first track, Pepperpot, I can certainly hear a lack of sympathy on Willie’s part. Again, I don’t know why. On the other hand, Art liked Wilbur Campbell a lot, and he just LOVED Steve Rodby -- who might have still been in his teens at this time. He liked Rodby so much, in fact, he brought him to New York for the Vanguard date. It was Elvin who complained. He said that Rodby was great, but much too green for what was about to happen. At the last minute George Mraz, an absolute genius in every way and quite mature enough for Elvin or anybody else, stepped in, read the hardest charts, and dealt philosophically with Art’s total insanity and brilliance. One more thing. -

Art Pepper Roadgame Mp3, Flac, Wma

Art Pepper Roadgame mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Roadgame Country: Italy Released: 1982 Style: Post Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1654 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1220 mb WMA version RAR size: 1219 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 950 Other Formats: AA AC3 DMF WAV FLAC APE VOX Tracklist Hide Credits Roadgame A1 9:30 Composed By – Pepper* Road Waltz A2 10:55 Composed By – Pepper* When You're Smiling B1 8:46 Composed By – Goodwin*, Shay*, Fisher* Everything Happens To Me B2 12:04 Composed By – Dennis*, Adair* Credits Alto Saxophone – Art Pepper (tracks: A1, A2, B2) Art Direction – Phil Carroll Bass – David Williams Clarinet – Art Pepper (tracks: B1) Design – Jamie Putnam Drums – Carl Burnett Engineer – Baker Bigsby Mastered By – George Horn Photography By – Steve Fitch Piano – George Cables Producer – Ed Michel Notes Recorded in performance at Maiden Voyage, Los Angeles, August 15, 1981, a full moon night. Mixed in Studio B, Fantasy Studios, Barkley. Mastered at Fantasy Studios. ℗ 1982, Galaxy Records. Marketed By Fonit Cetra - Made in Italy Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Roadgame (LP, GXY-5142 Art Pepper Galaxy GXY-5142 US 1982 Album) Original Jazz OJCCD 774-2 Art Pepper Roadgame (CD, RM) OJCCD 774-2 Germany 1993 Classics VIJ-6387, GXY Roadgame (LP, Galaxy, VIJ-6387, GXY Art Pepper Japan 1982 5142 Album) Galaxy 5142 Roadgame (LP, FAN 96-19 Art Pepper Fantasy FAN 96-19 Portugal 1982 Album) Roadgame (LP, GX 01-1279 Art Pepper Gamma GX 01-1279 Mexico 1982 Album) Related Music albums to Roadgame by Art Pepper Art Pepper Quartet - Live At Fat Tuesday's Art Pepper - The Complete Pacific Jazz Small Group Recordings Of Art Pepper Art Pepper - Friday Night At The Village Vanguard Richie Cole And .