Inactivation of the 455Th Chemical Brigade by Lieutenant Colonel John C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Hood AFGE

2002 Negotiated Agreement Fort Hood “people first – mission always” “Working together Works” AFGE Proud to Make America Work American Federation of Government Employees AFL-CIO Local, 1920 INDEX PREAMBLE 1 ARTICLE 1 EXCLUSIVE RECOGNITION AND COVERAGE OF AGREEMENT 2 ARTICLE 2 PURPOSE OF THIS AGREEMENT 3 ARTICLE 3 SCOPE OF CONSULTATION AND NEGOTIATION 4 ARTICLE 4 MANAGEMENT RIGHTS 6 ARTICLE 5 EMPLOYEE RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 7 ARTICLE 6 REPRESENTATION 9 ARTICLE 7 PUBLICITY 11 ARTICLE 8 EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY 12 ARTICLE 9 LABOR-MANAGEMENT COOPERATION 16 ARTICLE 10 HOURS OF WORK 16 ARTICLE 11 OVERTIME 19 ARTICLE 12 HOLIDAYS 20 ARTICLE 13 LEAVE 22 ARTICLE 14 EMPLOYEE PERSONNEL FILES 25 ARTICLE 15 JOB CLASSIFICATION 26 ARTICLE 16 TRAINING 26 ARTICLE 17 REDUCTION IN FORCE, REORGANIZATION, AND/OR TRANSFER OF FUNCTION 27 ARTICLE 18 DISCIPLINARY AND ADVERSE ACTIONS 28 ARTICLE 19 GRIEVANCE PROCEDURE 30 ARTICLE 20 ARBITRATION 34 ARTICLE 21 HEALTH AND SAFETY 36 ARTICLE 22 ON THE JOB INJURIES 39 ARTICLE 23 DUES WITHHOLDING 41 ARTICLE 24 EMPLOYEE ASSISTANCE PROGRAM (EAP) AND WORKPLACE VIOLENCE PROGRAM (WVP) 43 ARTICLE 25 USE OF OFFICIAL FACILITIES 45 ARTICLE 26 MERIT PROMOTION 46 ARTICLE 27 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM 48 ARTICLE 28 EMPLOYEE DEBTS 49 ARTICLE 29 INCENTIVE AWARDS 49 ARTICLE 30 ENVIRONMENTAL DIFFERENTIAL PAY 50 ARTICLE 31 FIREFIGHTERS 51 ARTICLE 32 GENERAL 53 ARTICLE 33 COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES PROGRAM 53 ARTICLE 34 PARKING 53 ARTICLE 35 IMPASSES IN NEGOTIATIONS 54 ARTICLE 36 TRAVEL AND PER DIEM 54 ARTICLE 37 SCHEDULED WITHIN-GRADE -

OP¥.K HANKS a Newspaper Vol

free oo Gis BALTIMORE GIs UNITED civilians 250 OP¥.K HANKS a newspaper Vol. 1, no. 3 IN SUPPORT OP DEMOCRACY Ft. Hoiabird The wars drag on. TEE GUARD FIASCO The poignant smell of death hangs heavy. Recently, a GI walking his guard A helicopter drones above the swamps post at the officer's club was shot In search of its prey: at by a would-be thief. Fortunately, The battered, broken bodies he was not hit. Since he was armed Of men. only with a small club and a flash Strong men once, light, the guard did not try to catch And brave and yo-ung. the thief. The duties and equipment But now they're older, of the guards have remained the same And tired— as before the shooting incident. Those who survived. What does the Chief of Staff ex A widow weeps. pect an untrained and virtually un A child cells out for Daddy, armed individual to do in the event Who promised he'd return. of trouble? The official answer is that the guard is supposed to report And he did. it so qualified help can get to the But silent, scene. That's fine unless the man and in a \rooden box. has stopped a bullet or been jumped And wars crag on. by drunks, in which case the report What are v/e searching for, America? will be made when the guard is found. And why? In the age of electronics, aren't And will v/e know what it is, there safer and much more efficient If and when we find it? ways to guard buildings than by post ing unarmed, untrained, sleepy, cold, LETTER TO. -

Lessons from Fort Hood: Improving Our Ability to Connect the Dots

LESSONS FROM FORT HOOD: IMPROVING OUR ABILITY TO CONNECT THE DOTS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 14, 2012 Serial No. 112–118 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 81–127 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana JOE WALSH, Illinois HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts BEN QUAYLE, Arizona KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia JANICE HAHN, California BILLY LONG, Missouri RON BARBER, Arizona JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas ROBERT L. TURNER, New York MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director/Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT MICHAEL T. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

2008 US Army Chemical Corps Hall of Fame Inductees

U.S. Army Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear School Army Chemical Review (ACR) (ISSN (573) XXX-XXXX 0899-7047) is prepared biannually by the U.S. DSN 676-XXXX (563 prefi x) or 581-XXXX (596 prefi x) Army Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear School and the Maneuver Support COMMANDANT Center Directorate of Training, Fort Leonard COL(P) Leslie C. Smith 563-8053 Wood, Missouri. ACR presents professional <[email protected]> information about Chemical Corps functions related to chemical, biological, radiological, and ASSISTANT COMMANDANT nuclear (CBRN); smoke; fl ame fi eld expedients; COL Greg D. Olson 563-8054 and reconnaissance in combat support. The <[email protected]> objectives of ACR are to inform, motivate, increase CHIEF OF STAFF knowledge, improve performance, and provide a LTC Doug Straka 563-8052 forum for the exchange of ideas. This publication <[email protected]> presents professional information, but the views expressed herein are those of the authors, not the COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR Department of Defense or its elements. The content CSM Ted A. Lopez 563-8053 does not necessarily refl ect the offi cial U.S. Army <[email protected]> position and does not change or supersede any DEPUTY ASSISTANT COMMANDANT–RESERVE information in other U.S. Army publications. The COMPONENT use of news items constitutes neither affi rmation COL Lawrence Meder 563-8050 of their accuracy nor product endorsement. <[email protected]> Articles may be reprinted if credit is given to ACR and its authors. All photographs are offi cial 3D CHEMICAL BRIGADE U.S. -

Fort Hood Community Information

Fort Hood Community Information January 24, 2018 Community Services Council (CSC) Key Events and Community Updates a. Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center (CRDAMC) COL David Gibson 2018 TRICARE Changes On Jan. 1, 2018, historic reform began rolling out in the Military Health System (MHS). A new era in TRICARE support contracts will improve health care delivery and enhance medical readiness. Core features of our reforms include improved access, simplified administration, and a modernized health plan. As part of this reform, TRICARE costs have changed. Beneficiaries now fall into one of two groups. Beneficiaries whose sponsor's initial enlistment or appointment occurred before Jan. 1, 2018 are in Group A. Those whose sponsor's initial enlistment or appointment occurred after Jan. 1, 2018 are in Group B. (Note: Those in premium- based plans now have Group B cost-shares regardless of when their sponsor first joined the service. Premium-based plans are: TRICARE Reserve Select (TRS), TRICARE Retired Reserve (TRR), TRICARE Young Adult (TYA), and Continued Health Care Benefit Program (CHCBP). In addition, more preventive services will be covered under TRICARE Select at no cost than were covered under TRICARE Standard and Extra if they are provided by a network provider. 2018 TRICARE Pharmacy Changes Beginning February 1, 2018, TRICARE pharmacy copayments will be changing for all beneficiaries, except Active Duty Service Members (ADSMs), dependent survivors of ADSMs, and medically retired service members and their dependents. The changes are required by United States federal law, with the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018. Copayments for generic drugs, brand name drugs, and non-formulary drugs are increasing across the retail and home delivery points of service. -

By COL Charles Maskell, Unites States Army

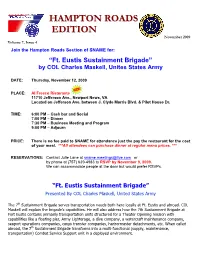

HHAAMMPPTTOONN RROOAADDSS EEDDIITTIIOONN November 2009 Volume 7, Issue 4 Join the Hampton Roads Section of SNAME for: “Ft. Eustis Sustainment Brigade” by COL Charles Maskell, Unites States Army DATE: Thursday, November 12, 2009 PLACE: Al Fresco Ristorante 11710 Jefferson Ave., Newport News, VA Located on Jefferson Ave. between J. Clyde Morris Blvd. & Pilot House Dr. TIME: 6:00 PM – Cash bar and Social 7:00 PM – Dinner 7:30 PM – Business Meeting and Program 9:00 PM – Adjourn PRICE: There is no fee paid to SNAME for attendance just the pay the restaurant for the cost of your meal. ***All attendees can purchase dinner at regular menu prices. *** RESERVATIONS: Contact Julie Lane at [email protected] or by phone at (757) 639-4983 to RSVP by November 9, 2009. We can accommodate people at the door but would prefer RSVPs. “Ft. Eustis Sustainment Brigade” Presented By COL Charles Maskell, United States Army The 7th Sustainment Brigade serves transportation needs both here locally at Ft. Eustis and abroad. COL Maskell will explain the brigade’s capabilities. He will also address how the 7th Sustainment Brigade at Fort Eustis contains primarily transportation units structured for a Theater Opening mission with capabilities like a floating pier, Army Lighterage, a dive company, a watercraft maintenance company, seaport operations companies, cargo transfer companies, harbormaster detachments, etc. When called abroad, the 7th Sustainment Brigade transforms into a multi-functional (supply, maintenance, transportation) Combat Service Support unit in a deployed environment. About Our Speaker: Colonel Charles Maskell, U.S. Army - 7th Sustainment Brigade Colonel Maskell was born 15 September 1963 in New London, Connecticut. -

NMMI Army ROTC Early Commissioning Program ROTC

NMMI Army ROTC Early Commissioning Program ROTC Handbook Part 3 – Military Science IV (Sophomore Year at NMMI) Military Science and Leadership IV 1 New Cadet Cadre 2 Administrative Requirements Prior to Commissioning 3 Commissioning 4 Education Assistance Program 5 The “Silver Dollar” Salute 6 Officers Creed 6 Accessions Process 6 National Order of Merit List Criteria: OML Model 8 Gold Bar Recruiting 8 Military Science and Leadership IV The MSL 401 and 402 courses comprise your second year of ROTC classes and are a part of your NMMI academic schedule. In addition to your classroom responsibilities, you will now comprise the leadership of the ROTC Battalion and will take an active role in planning, resourcing, and conducting training. Overview of MSL 401: Mission Command and the Army Profession In this course, you will explore the dynamics of leading in the complex situations of current military operations. You will examine differences in customs and courtesies, military law, principles of war, and rules of engagement in the face of international terrorism. You also explore aspects of interacting with non-government organizations, civilians on the battlefield, the decision making processes and host nation support. The course places significant emphasis on preparing you for BOLC B and your first unit of assignment. It uses mission command case studies and scenarios to prepare you to face the complex ethical demands of serving as a commissioned officer in the United States Army. This semester, you will: Explore military professional ethics, organizational ethics and ethical decision making processes 1 Gain practical experience in Cadet battalion leadership roles and training management Begin your leadership self-development including civil military and media relations Prepare for the transition to a career as an Army Officer Overview of MSL 402: Mission Command and the Company Grade Officer In this course, you will explore the dynamics of leading in the complex situations during Unified Land Operations I, II, and III. -

Fort Hood Community Information

Fort Hood Community Information March 28, 2018 Community Services Council (CSC) Key Events and Community Updates a. Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center (CRDAMC) LTC Devry Anderson Optometry Appointments For Active Duty, TRICARE enrolled Family Members and Retirees No referral needed Russell Collier, Bennett, Thomas Moore and Monroe Clinics For more information or to schedule an appointment, call (254) 288-8888. Corrective Eye Surgery – Active Duty Soldiers 3 procedures available: Laser eye (LASIK) surgery Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) surgery Implantable contact lens (ICL) surgery Soldiers may qualify if they have18 months or more left on their contract Must obtain a refractive surgery permission form from any Optometry clinic Submit completed form and a copy of Enlisted Record Brief (ERB)/Officer Record Brief (ORB) to the Opthamology clinic at the main hospital For more information, call (254) 288-8491 or (254) 286-7952 from 7:30 am – 4:30 pm. Community Based Medical Home #4 – Bunny Trail, Killeen, TX During Initial Operational Capability (IOC): Enrollment shift from Fort Hood Medical Home (on post) to Bunny Trail (off post) Beneficiaries can move to new clinic or remain on post Supports 5,500 Family Members and Retirees Lab and Pharmacy services will only be provided to beneficiaries enrolled in the clinic Opening summer of 2018 (T) Full Operational Capability (FOC): Same Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model as Killeen, Harker Heights and Copperas Cove Will support 8,500 Family Members and Retirees Drive-thru -

USAG Fort Hood Fact Sheet (3 March 2017)

USAG Fort Hood Fact Sheet (3 March 2017) FORT HOOD POPULATION REAL PROPERTY SUMMARY ON POST POPULATION 61,247 TOTAL ACREAGE: 218,823 (342 sq. mi.; 886 sq. km) RANGE AND TRAINING LAND: 196,797 (MANEUVER: 132,525; Live Fire & Range: 64,272) Military Assigned ( includes deployed: 3,728 ) 35,577 BUILDINGS and STRUCTURES: 5,988 (37.3M sq. ft.; 3.5M sq. meters of floor space) On Post Family Members 13,169 FAMILY QUARTERS: 5,849 in 12 separate housing areas. Occupancy rate 91% SOLDIER BARRACKS: 99 total with 15,688 beds. Occupancy rate 79% Civilian Employees - AF 4,768 CANTONMENT: 22,026 acres Civilian Employees - NAF 833 RANGES AND TRAINING AREAS: Contractor Personnel and Others 4,677 SMALL ARMS: 75 AAFES 1,292 TANK/BRADLEY/STRYKER MULTI-PURPOSE RANGE: 11 Commissaries 171 UNMANNED AERIAL SYSTEM LANDING STRIPS (SHADOW): 2 UNMANNED AIRCRAFT: 2 Gray Eagle Companies (12 AC) & 1 Hunter Company (6 AC) KISD On Post Schools (Staff & Employees) 760 UNIMPROVED LANDING STRIPS (C-17 CAPABLE): 1 AIRBORNE DROP ZONES: 2 SUPPORTED POPULATION 383,526 URBAN TRAINING AREAS: 10 Retirees, Survivors & Family Members (updated Oct 16)290,996 UNDERGROUND TRAINING FACILITY: 2 On Post Population 57,519 AIRFIELDS: Off-Post Family Members 35,011 ROBERT GRAY ARMY AIRFIELD AT WEST FORT HOOD (7 hangars) US ARMY GARRISON ANNUAL OPERATING BUDGET - Joint Use with Killeen-Fort Hood Regional Airport HOOD ARMY AIRFIELD (east side of main cantonment) (10 hangars) O M A 2020: AFH 0725 LONGHORN AUXILIARY AIRSTRIP (North Fort Hood) FY16-Executed $407,317,500 $1,322,900 SHORTHORN AUXILIARY -

Military Family Guide to Fort Hood

Military Family Guide to Fort Hood A publication of Table of Contents 1. Welcome to Fort Hood 2. Area Military Installations 3. What to Expect 4. Weather & Climate 5. Area Attractions 6. Neighborhoods 7. Schools & Education 8. Military Spouse Information 9. Helpful Links If you love grapefruit, sweet onions, and armor-plated armadillos, you’re going to feel right at home in the Lone Star State. But, if you don’t care for the official state symbols, you’re in luck, because everyone loves the state flower, Bluebonnets! Welcome to Army pride is strong on Fort Fort Hood! Hood because it’s home to the 1st Cavalry Division, the largest armored division in the United States. It’s easy to see why Fort Hood is nicknamed “The Great Place.” Those who live here agree quality of life is high—especially if you appreciate long, humid summers and pleasantly snowless winters. Fort Hood Area Military Installations Located between Waco and Austin, Fort Hood, Texas, is the largest active duty U.S. military installation. The post is over 300 square miles--so if you aren’t already familiar with the area, you might feel a little overwhelmed when you get orders to PCS there. Since it’s such a large installation, it’s important to know which side of the post your service member will spend most of his or her time. The base has three main entrances: Clear Creek Gate, TJ Mills Gate, and WS Young Gate. Getting Around Fort Hood Map courtesy Military Town Advisor Killeen is a typical military town with a lot of chain restaurants, big brand stores, and strip malls. -

Rail Park at Central Pointe Temple, Texas

Rail Park at Central Pointe ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Temple, Texas Tracking For Success Rail Park at Central Pointe is a 306 acre site in Temple, Texas that Vancouver ! has been designated as a BNSF Certified Site. BNSF certification ensures a site is ready for rapid acquisition! and development Winnipeg ! Seattle through a comprehensive! evaluation of existing and projected ! Havre ! infrastructure,Spokane environmental Minotand geotechnical standards, utility ! Fargo Portland evaluation and site availability. ! ! Superior ! Billings Minneapolis SELECTING A CERTIFIED SITE CAN: !! St. Paul ! • Reduce developmentGillette time ! Sioux Falls Chicago • Increase speed to market ! ! Alliance Galesburg ! • Reduce upfront! Salt Lake Citydevelopment risk of rail-served industrial sites ! Lincoln ! ! ! Stockton Denver Topeka ! ! ! Oakland Kansas City St. Louis PROPERTY DETAILS Springeld ! The property known as Rail Park at Central Pointe is located within Temple’s established Memphis ! ! ! Atlanta Los Angeles ! ! !Albuquerque ! Oklahoma City ! and highly successful industrial! districtSan Bernardino Winslow Birmingham Long Beach Belen ! Amarillo ! comprising of over 4,900 acres for existing ! San Diego ! Phoenix and future development. The industrial Fort Worth ! park is a major initiative by the Temple ! El Paso Economic Development Corporation and New Orleans ! TEMPLE, TX Houston includes Airport and Enterprise Parks at Austin! ! San Antonio Central Pointe. ! Temple’s certified site contains approximately 10 miles of track switched by the Temple & Central Texas Railway, connecting solely to BNSF. With 306 acres for development, this certified site is ideal for an industrial tenant seeking a large, rail-served site that is positioned for quick and relatively easy development. CONTACT INFORMATION Site Details: BNSF Regional Manager • 306 available acres Gary Laffoon 817.867.0763 • Direct rail access to BNSF [email protected] • Over $16 million in road and utility upgrades • Direct access to Interstate 35 and proximity to U.S.