Chap – 6 : Hybridization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advances on Research Epigenetic Change of Hybrid and Polyploidy in Plants

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 10(51), pp. 10335-10343, 7 September, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB DOI: 10.5897/AJB10.1893 ISSN 1684–5315 © 2011 Academic Journals Review Advances on research epigenetic change of hybrid and polyploidy in plants Zhiming Zhang†, Jian Gao†, Luo Mao, Qin Cheng, Zeng xing Li Liu, Haijian Lin, Yaou Shen, Maojun Zhao and Guangtang Pan* Maize Research Institute, Sichuan Agricultural University, Xinkang road 46, Ya’an, Sichuan 625014, People’s Republic of China. Accepted 15 April, 2011 Hybridization between different species, and subsequently polyploidy, play an important role in plant genome evolution, as well as it is a widely used approach for crop improvement. Recent studies of the last several years have demonstrated that, hybridization and subsequent genome doubling (polyploidy) often induce an array of variations that could not be explained by the conventional genetic paradigms. A large proportion of these variations are epigenetic in nature. Epigenetic can be defined as a change of the study in the regulation of gene activity and expression that are not driven by gene sequence information. However, the ramifications of epigenetic in plant biology are immense, yet unappreciated. In contrast to the ease with which the DNA sequence can be studied, studying the complex patterns inherent in epigenetic poses many problems. In this view, advances on researching epigenetic change of hybrid and polyploidy in plants will be initially set out by summarizing the latest researches and the basic studies on epigenetic variations generated by hybridization. Moreover, polyploidy may shed light on the mechanisms generating these variations. -

Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution Refers to Varieties Within a Given Type

Chapter 8: Evolution Lesson 8.3: Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution refers to varieties within a given type. Change happens within a group, but the descendant is clearly of the same type as the ancestor. This might better be called variation, or adaptation, but the changes are "horizontal" in effect, not "vertical." Such changes might be accomplished by "natural selection," in which a trait within the present variety is selected as the best for a given set of conditions, or accomplished by "artificial selection," such as when dog breeders produce a new breed of dog. Lesson Objectives ● Distinguish what is microevolution and how it affects changes in populations. ● Define gene pool, and explain how to calculate allele frequencies. ● State the Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● Identify the five forces of evolution. Vocabulary ● adaptive radiation ● gene pool ● migration ● allele frequency ● genetic drift ● mutation ● artificial selection ● Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● natural selection ● directional selection ● macroevolution ● population genetics ● disruptive selection ● microevolution ● stabilizing selection ● gene flow Introduction Darwin knew that heritable variations are needed for evolution to occur. However, he knew nothing about Mendel’s laws of genetics. Mendel’s laws were rediscovered in the early 1900s. Only then could scientists fully understand the process of evolution. Microevolution is how individual traits within a population change over time. In order for a population to change, some things must be assumed to be true. In other words, there must be some sort of process happening that causes microevolution. The five ways alleles within a population change over time are natural selection, migration (gene flow), mating, mutations, or genetic drift. -

NOTES – CH 17 – Evolution of Populations

NOTES – CH 17 – Evolution of Populations ● Vocabulary – Fitness – Genetic Drift – Punctuated Equilibrium – Gene flow – Adaptive radiation – Divergent evolution – Convergent evolution – Gradualism 17.1 – Genes & Variation ● Darwin developed his theory of natural selection without knowing how heredity worked…or how variations arise ● VARIATIONS are the raw materials for natural selection ● All of the discoveries in genetics fit perfectly into evolutionary theory! Genotype & Phenotype ● GENOTYPE : the particular combination of alleles an organism carries ● an organism’s genotype, together with environmental conditions, produces its PHENOTYPE ● PHENOTYPE : all physical, physiological, and behavioral characteristics of an organism (i.e. eye color, height ) Natural Selection ● NATURAL SELECTION acts directly on… …PHENOTYPES ! ● How does that work?...some individuals have phenotypes that are better suited to their environment…they survive & produce more offspring (higher fitness!) ● organisms with higher fitness pass more copies of their genes to the next generation! Do INDIVIDUALS evolve? ● NO! ● Individuals are born with a certain set of genes (and therefore phenotypes) ● If one or more of their phenotypes (i.e. tooth shape, flower color, etc.) are poorly adapted, they may be unable to survive and reproduce ● An individual CANNOT evolve a new phenotype in response to its environment So, EVOLUTION acts on… ● POPULATIONS! ● POPULATION = all members of a species that live in a particular area ● In a population, there exists a RANGE of phenotypes ● NATURAL SELECTION acts on this range of phenotypes the most “fit” are selected for survival and reproduction 17.2: Evolution as Genetic Change in Populations Mechanisms of Evolution (How evolution happens) 1) Natural Selection (from Darwin) 2) Mutations 3) Migration (Gene Flow) 4) Genetic Drift DEFINITIONS: ● SPECIES: group of organisms that breed with one another and produce fertile offspring. -

Lecture 9: Population Genetics

Lecture 9: Population Genetics Plan of the lecture I. Population Genetics: definitions II. Hardy-Weinberg Law. III. Factors affecting gene frequency in a population. Small populations and founder effect. IV. Rare Alleles and Eugenics The goal of this lecture is to make students familiar with basic models of population genetics and to acquaint students with empirical tests of these models. It will discuss the primary forces and processes involved in shaping genetic variation in natural populations (mutation, drift, selection, migration, recombination, mating patterns, population size and population subdivision). I. Population genetics: definitions Population – group of interbreeding individuals of the same species that are occupying a given area at a given time. Population genetics is the study of the allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the 4 evolutionary forces: natural selection, mutation, migration (gene flow), and genetic drift. Population genetics is concerned with gene and genotype frequencies, the factors that tend to keep them constant, and the factors that tend to change them in populations. All the genes at all loci in every member of an interbreeding population form gene pool. Each gene in the genetic pool is present in two (or more) forms – alleles. Individuals of a population have same number and kinds of genes (except sex genes) and they have different combinations of alleles (phenotypic variation). The applications of Mendelian genetics, chromosomal abnormalities, and multifactorial inheritance to medical practice are quite evident. Physicians work mostly with patients and families. However, as important as they may be, genes affect populations, and in the long run their effects in populations have a far more important impact on medicine than the relatively few families each physician may serve. -

1 Genepool: Exploring the Interaction Between Natural Selection and Sexual Selection

1 GenePool: Exploring The Interaction Between Natural Selection and Sexual Selection Jeffrey Ventrella Gene Pool is an artificial life simulation designed to bring some basic principles of evolution to light in an entertaining and instructive way. Most significant is the aspect of sexual selection — where mate choice is a factor in the evolution of morphology and motor-control in physically-based animated organisms. We see in the examples of deer antlers, peacock tails, and fish coloration a magnificent world of variation that makes the study of animals fascinating for us — aesthetically — driven humans that we are. But aesthetics is in the eye of the beholder. And sometimes aesthetics can run counter to the rules of basic survival. Gene Pool was designed to explore this topic. 1.0.1 History In 1996, an animated artificial life simulation, called Darwin Pond, was designed, and a paper was published describing the simulation [13]. In Darwin Pond, hundreds of physically-based organisms achieve locomotion via genetically-based motor con- trol and morphology. The ability to have more offspring is a direct outcome of two factors: 1) better ability to swim to within a critical distance to a chosen mate, and 2), the ability to attract other organisms who want to mate. Because Darwin Pond was developed at a computer game company (Rocket Sci- ence Games, Inc.) it included a significant interactive component.Rocket Science did not survive as a company, and after much effort, Darwin Pond was released from the corporate and legal complexities of the software games world, and it was published for free at, where it has remained. -

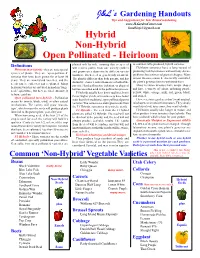

Hybrid Non-Hybrid Open Pollinated - Heirloom Planted Side by Side, Ensuring That Every Seed to Commercially-Produced, Hybrid Varieties

J&L’s Gardening Handouts Tips and Suggestions for Year Round Gardening www.JLGardenCenter.com [email protected] 2018 Hybrid Non-Hybrid Open Pollinated - Heirloom planted side by side, ensuring that every seed to commercially-produced, hybrid varieties. Definitions will receive pollen from one variety (father) Heirloom tomatoes have a long record of Heirloom (non-hybrid) - they are not a special and grown on a distinctively different variety producing healthy tomatoes without many disease species of plants. They are ‘open-pollinated’ (mother). Each seed is genetically identical. problems; but commercial growers disagree. Many varieties that have been grown for at least 50 The plant is different than both parents, and has tomato diseases cannot be chemically controlled; years. They are non-hybrid varieties, and the distinctive characteristics from one or both of the the plant’s genetics have to withstand them. seeds can be collected and re-planted. Many parents. Hand pollination, isolation, or physical Many heirloom tomatoes have unique shapes heirloom varieties are not used in modern ‘large- barriers are often used in the pollination process. and have a variety of colors, including purple, scale’ agriculture, but they are used extensively F1 hybrids usually have better qualities, better yellow, white, orange, pink, red, green, black, in home gardens. flavor, higher yields, or in some way have better and striped. Open pollinated (non-hybrid) - Pollination traits than their traditional, open pollinated parent However, some gardeners don’t want unusual, occurs by insects, birds, wind, or other natural varieties. You cannot save and replant seeds from misshapen, or inconsistent tomatoes. They simply mechanisms. -

Chapter 8 an Introduction to Population Genetics

Chapter 8 An Introduction to Population Genetics Matthew E. Andersen Department of Biological Sciences University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-4004 Matthew Andersen received his B.A. in 1986 from Sonoma State University, California. He was an honors student for his undergraduate work and is now a doctoral student at UNLV. He has worked in biomedical research and as a pathologist's assistant. His Ph.D. research is on the molecular systematics of fish, particularly speckled dace, Rhinichthys osculus (Cyprinidae). Reprinted from: Andersen, M. E. 1993. An introduction to population genetics. Pages 141-152, in Tested studies for laboratory teaching, Volume 14 (C. A. Goldman, Editor). Proceedings of the 14th Workshop/Conference of the Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE), 240 pages. - Copyright policy: http://www.zoo.utoronto.ca/able/volumes/copyright.htm Although the laboratory exercises in ABLE proceedings volumes have been tested and due consideration has been given to safety, individuals performing these exercises must assume all responsibility for risk. The Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE) disclaims any liability with regards to safety in connection with the use of the exercises in its proceedings volumes. © 1993 Matthew E. Andersen 141 Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE) ~ http://www.zoo.utoronto.ca/able 142 Population Genetics Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................142 Student -

Oreochromis Niloticus and O. Mossambicus F1

SalinitySalinity ToleranceTolerance ofof OreochromisOreochromis niloticusniloticus andand O.O. mossambicusmossambicus F1F1 HybridsHybrids andand TheirTheir SuccessiveSuccessive BackcrossBackcross Dennis A. Mateo, Riza O. Aguilar, Wilfredo Campos, Ma. Severa Fe Katalbas, Roman Sanares, Bernard Chevassus, Jerome Lazard, Pierre Morissens, Jean Francois Baroiller and Xavier Rognon Significance of the Study • Freshwater now becoming a scarce resource, with competing use for: • Domestic or household, agriculture and power generation. • Future prospect in aquaculture: • Expansion to saline waters, unfit for domestic/household and agricultural uses. • Fish cage culture in saline waters. • Alternative species for brackishwater pond culture. • Tilapias are popular cultured species due to their high environmental tolerances. • Tilapias posses various characteristics which make them desirable species for brackishwater farming. • Consequently, for many years, tropical aquaculturists have tried to develop saline tilapia culture. • Unfortunately, the true brackishwater tilapias (e.g. O. mossambicus) have poor- growing performance while the fast- growing strains (e.g. O. niloticus) are poorly adapted to saline water environment. • The usual practice of using F1 hybrids of the foregoing species failed. Why F1 hybrids failed? • Difficult to maintain two pure species; small production due to incompatibility of breeders; and unsustainable mass production. • With the foregoing reasons, there is a need to produce tilapia strains that can be bred in brackishwater. -

A Glossary of Terms for Restoration Genetics

Paul R. Salon Allele – The specific composition of DNA at each gene is known as an allele. Multiple alleles of a gene maybe A Glossary of Terms for Restoration Genetics USDA-NRCS Syracuse, NY generated by mutations which are structural or chemical changes in DNA at a specific location on a chromosome (locus), this generates genetic variation. Genetic shift – A change in the germplasm balance of a cross pollinated variety, usually caused by Biodiversity - The total variability within and among species of living organisms and the ecological complexes environmental selection pressures, or nursery practices and selection. that they inhabit. Biodiversity has three levels - ecosystem, species, and genetic diversity reflected in the Genetic vulnerability - Having a narrow range of genetic diversity and reacting uniformly to diverse external number of different species, the different combination of species, and the different combinations of genes within conditions. (Applied to breeding populations of varieties or species). each species. Genotype - The genetic constitution of an individual or group of plants. It is the set of alleles it possesses at a Biotype - A group of individuals within a population occurring in nature, all with essentially the same genetic certain locus or over particular or all loci. constitution. A species usually consists of many biotypes. See also “ecotype”. Germplasm – Genetic material that determines the morphological and physiological characteristics of a species. Chromosomes - Are thread like DNA and protein-based structures in cells whose function is the orderly duplication and distribution of genes during cell division. Heterozygote – If alleles at a locus are different. Cultivar - The international term cultivar denotes an assemblage of cultivated plants that is clearly distinguished Homozygote – If alleles at a locus are the same, the locus is homozygous and the organism is a homozygote for that by any characters (morphological, physiological, cytological, chemical, or others) and when reproduced (sexually gene or trait. -

Biological Invasions at the Gene Level VIEWPOINT Rémy J

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2004) 10, 159–165 Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. BIODIVERSITY Biological invasions at the gene level VIEWPOINT Rémy J. Petit UMR Biodiversité, Gènes et Ecosystèmes, 69 ABSTRACT Route d’Arcachon, 33612 Cestas Cedex, France Despite several recent contributions of population and evolutionary biology to the rapidly developing field of invasion biology, integration is far from perfect. I argue here that invasion and native status are sometimes best discussed at the level of the gene rather than at the level of the species. This, and the need to consider both natural (e.g. postglacial) and human-induced invasions, suggests that a more integrative view of invasion biology is required. Correspondence: Rémy J. Petit, UMR Key words Biodiversité, Gènes et Ecosystèmes, 69 Route d’Arcachon, 33612 Cestas Cedex, France. Alien, genetic assimilation, gene flow, homogenization, hybridization, introgression, E-mail: [email protected] invasibility, invasiveness, native, Quercus, Spartina. the particular genetic system of plants. Although great attention INTRODUCTION has been paid to the formation of new hybrid taxa, introgression Biological invasions are among the most important driving more often results in hybrid swarms or in ‘genetic pollution’, forces of evolution on our human-dominated planet. According which is best examined at the gene level. Under this perspective, to Myers & Knoll (2001), distinctive features of evolution now translocations of individuals and even movement of alleles include a homogenization of biotas, a proliferation of opportunistic within a species’ range (e.g. following selective sweeps) should species, a decline of biodisparity (the manifest morphological equally be recognized as an important (if often cryptic) and physiological variety of biotas), and increased rates of speci- component of biological invasions. -

Outline 09/10/2014 Louisville Seed Library Seed Saving

Outline 09/10/2014 Louisville Seed Library Seed Saving Define the following: 1. Heirloom Seed a. An heirloom is generally considered to be a variety that has been passed down, through several generations of a family because of it's valued characteristics. Since 'heirloom' varieties have become popular in the past few years there have been liberties taken with the use of this term for commercial purposes. b. Commercial Heirlooms: Open-pollinated varieties introduced before 1940, or tomato varieties more than 50 years in circulation. c. Family Heirlooms: Seeds that have been passed down for several generations through a family. d. Created Heirlooms: Crossing two known parents (either two heirlooms or an heirloom and a hybrid) and dehybridizing the resulting seeds for how ever many years/generations it takes to eliminate the undesirable characteristics and stabilize the desired characteristics, perhaps as many as 8 years or more. e. Mystery Heirlooms: Varieties that are a product of natural cross-pollination of other heirloom varieties. f. (Note: All heirloom varieties are open-pollinated but not all open-pollinated varieties are heirloom varieties.) 2. Open Pollinated Seed a. Open pollinated or OP plants are varieties that grow true from seed. This means they are capable of producing seeds from this seasons plants, which will produce seedlings that will be just like the parent plant. 3. Organic a. Organic 1. USDA Definition and Regulations:The Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA), enacted under Title 21 of the 1990 Farm Bill, served to establish uniform national standards for the production and handling of foods labeled as “organic.” The Act authorized a new USDA National Organic Program (NOP) to set national standards for the production, handling, and processing of organically grown agricultural products. -

Chapter 6 the Gene Pool Concept Applied to Crop Wild Relatives

Published by: Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Citation: Miller RE and Khoury CK (2018) “The Gene Pool Concept Applied to Crop Wild Relatives: An Evolutionary Perspective”. In: Greene SL, Williams KA, Khoury CK, Kantar MB, and Marek LF, eds., North American Crop Wild Relatives, Volume 1: Conservation Strategies. Springer, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-95101-0_6. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95101-0_6 https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-319-95101-0_6 Chapter 6 The Gene Pool Concept Applied to Crop Wild Relatives: An Evolutionary Perspective Richard E. Miller* and Colin K. Khoury Richard E. Miller, 407 East Charles Street, Hammond, Louisiana 70401, [email protected] *corresponding author Colin K. Khoury, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Center for Agricultural Resources Research, National Laboratory for Genetic Resource Preservation, Fort Collins, CO USA and International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Cali, Colombia, [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Crop wild relatives (CWR) can provide important resources for the genetic improvement of cultivated species. Because crops are often related to many wild species and because exploration of CWR for useful traits can take many years and substantial resources, the categorization of CWR based on a comprehensive assessment of their potential for use is an important knowledge foundation for breeding programs. The initial approach for categorizing CWR was based on crossing studies to empirically establish which species were interfertile with the crop. The foundational concept of distinct gene pools published almost 50 years ago was developed from these observations. However, the task of experimentally assessing all potential CWR proved too vast; therefore, proxies based on phylogenetic and other advanced scientific information have been explored.