How Hollywood Films Portray Illness Robert A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At Home with the Movies

At Home with the Movies PAT COSTA THE BOBO (1967) Friday, May 26 (NBC) He plays a Russian-British Thursday, May 25 (CBS) double agent and Mia Farrow is The regular Friday night NBC the love interest, naturally. The As I A poorly-done comedy starring movie is. pre-empted this night best parts are taken by Tom Peter Sellers, this is about an ex- for Chronolog, the documentary Courtenay, Per Oscarsson and matador from Barcelona who de series that everyone says they Lionel Stander in supporting cides to become a singer and se watch when pollsters call to ask roles.- See It duce a high-class prostitute which programs are being played by Britt Ekland. viewed. It was rated A-3, unobjection able for adults, by the national Rossano Brazzi and Adolfo Catholic film office. Celi are lost in supproting roles. TOPAZ (1970) Those who watched the televi supporting awards for their The national Catholic film of Saturday, May 27 sion industry present itself a- work on "The Mary Tyler Moore fice rated this A-3, unobjection wards for 2'/s hours recently at A foreign-intrigue adventuite THE SINGING NUN (1966) Show", gave extended credit able "for adults. Monday, May 29 (NBC) the 24th annual Emmy show to the writers on that situation drama, this one uses the Cuban could have learned a lot about comedy, which is one of the best missile crisis as its launching A syrupy concoction starring this medium. written fun shows of ail time. Gabrielli pad, with John Forsyth the only Debbie Reynolds as a constantly jiame in the cast that hops from cheerful nun who manages a rec And probably the first lesson Lesson three could deal with Speaks in country to country in this politi ord contract in between serving was that TV knows no more another background job so cal cloak and dagger film. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

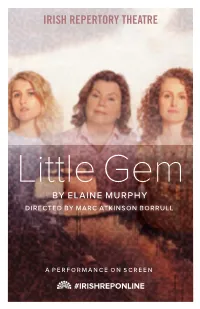

Digital Playbill

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE Little Gem BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN LITTLE GEM BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL STARRING BRENDA MEANEY, LAUREN O'LEARY AND MARSHA MASON scenic design costume design lighting design sound design & original music sound mix MEREDITH CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL RYAN M.FLORIAN RIES METZGER O'CONNOR RUMERY STAAB edited by production coordinator production coordinator SARAH ARTHUR REBECCA NICHOLS ATKINSON MONROE casting press representatives general manager DEBORAH BROWN MATT ROSS LISA CASTING PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE North Dublin, 2008 Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission. SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre wishes to thank Henry Clarke, Olivia Marcus, Melanie Spath, and the Howard Gilman Foundation. Little Gem is produced under the SAG-AFTRA New Media Contract. THE ORIGINAL 2019 PRODUCTION OF LITTLE GEM ALSO FEATURED PROPS BY SVEN HENRY NELSON AND SHANNA ALISON AS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST MARSHA MASON (Kay) has summer 2019, Marsha starred in Irish received an Outer Critics Rep’s acclaimed production of Little Gem Circle Award and 4 Academy and directed a reading of The Man Who Awards nominations for her Came to Dinner with Brooke Shields and roles in the films “The Goodbye Walter Bobbie at the Bucks County Girl,” “Cinderella Liberty,” Playhouse and WP Theater in NYC. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

July 1979 • Volume Iv • Number Vi

THE FASTEST GROWING CHURCH IN THE WORLD by Brother Keith E. L'Hommedieu, D.D. quite safe tosay that ofall the organized religious sects on the current scene, one church in particular stands above all in its unique approach to religion. The Universal LifeChurch is the onlyorganized church in the world withno traditional religious doctrine. Inthe words of Kirby J. Hensley,founder, "The ULC only believes in what is right, and that all people have the right to determine what beliefs are for them, as long as Brother L 'Hommed,eu 5 Cfla,r,nan right ol the Board of Trusteesof the Sa- they do not interferewith the rights ofothers.' cerdotal Orderof the Un,versalL,fe andserves on the Board of O,rec- Reverend Hensley is the leader ofthe worldwide torsOf tOe fnternahOna/ Uns'ersaf Universal Life Church with a membership now L,feChurch, Inc. exceeding 7 million ordained ministers of all religious bileas well as payfor traveland educational expenses. beliefs. Reverend Hensleystarted the church in his NOne ofthese expenses are reported as income to garage by ordaining ministers by mail. During the the IRS. Recently a whole town in Hardenburg. New 1960's, he traveled all across the country appearing York became Universal Life ministers and turned at college rallies held in his honor where he would their homes into religious retreatsand monasteries perform massordinations of thousands of people at a thereby relieving themselves of property taxes, at time. These new ministers were then exempt from least until the state tries to figure out what to do. being inducted into the armed forces during the Churches enjoycertain othertax benefits over the undeclared Vietnam war. -

Acting Without Bullshit

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 3 March 2020 (pp. 7-15) ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Acting without Bullshit Dr. Rodney Whatley 2190 White Pines Drive Pensacola, FL 32526 Abstract This article is a guide to honest acting. Included is a discussion that identifies dishonest acting and the actor training that results in it. A definition of what truth onstage consists of is contrasted with a description of impractical acting exercises that should be avoided. The consequences of acting with bullshit are revealed. The article concludes with a description of the most practical and honest acting exercise. If you are a performance artist who loves shows with no dialogue, characters without names, or an unconnected series of events in lieu of plot, this essay isn’t for you. If you are an artist who communicates with sounds instead of words, this isn’t for you. However, if you like plots with specific characters pursuing superobjectives despite conflict, that explores the human condition, this essay is for you. This is a guide to practical, straightforward and honest acting. The actor must be honest in the relationship with the audience because you can’t shit a shitter, so don’t try. How can actors be honest onstage when acting is lying? By studying with good acting teachers who teach good acting classes, and aye, there’s the rub. Bad acting teachers train actors to get lost within their own reality, to surround themselves with the “magic” of acting and “become the character.” This teaches that the goal of acting is to convince the audience that the actor is the character. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Chapter 3: the Rise of the Antinuclear Power Movement: 1957 to 1989

Chapter 3 THE RISE OF THE ANTINUCLEAR POWER MOVEMENT 1957 TO 1989 In this chapter I trace the development and circulation of antinuclear struggles of the last 40 years. What we will see is a pattern of new sectors of the class (e.g., women, native Americans, and Labor) joining the movement over the course of that long cycle of struggles. Those new sectors would remain autonomous, which would clearly place the movement within the autonomist Marxist model. Furthermore, it is precisely the widening of the class composition that has made the antinuclear movement the most successful social movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Although that widening has been impressive, as we will see in chapter 5, it did not go far enough, leaving out certain sectors of the class. Since its beginnings in the 1950s, opposition to the civilian nuclear power program has gone through three distinct phases of one cycle of struggles.(1) Phase 1 —1957 to 1967— was a period marked by sporadic opposition to specific nuclear plants. Phase 2 —1968 to 1975— was a period marked by a concern for the environmental impact of nuclear power plants, which led to a critique of all aspects of nuclear power. Moreover, the legal and the political systems were widely used to achieve demands. And Phase 3 —1977 to the present— has been a period marked by the use of direct action and civil disobedience by protesters whose goals have been to shut down all nuclear power plants. 3.1 The First Phase of the Struggles: 1957 to 1967 Opposition to nuclear energy first emerged shortly after the atomic bomb was built. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

Filmography 1963 Through 2018 Greg Macgillivray (Right) with His Friend and Filmmaking Partner of Eleven Years, Jim Freeman in 1976

MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography 1963 through 2018 Greg MacGillivray (right) with his friend and filmmaking partner of eleven years, Jim Freeman in 1976. The two made their first IMAX Theatre film together, the seminal To Fly!, which premiered at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum on July 1, 1976, one day after Jim’s untimely death in a helicopter crash. “Jim and I cared only that a film be beautiful and expressive, not that it make a lot of money. But in the end the films did make a profit because they were unique, which expanded the audience by a factor of five.” —Greg MacGillivray 2 MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography Greg MacGillivray: Cinema’s First Billion Dollar Box Office Documentarian he billion dollar box office benchmark was never on Greg MacGillivray’s bucket list, in fact he describes being “a little embarrassed about it,” but even the entertainment industry’s trade journal TDaily Variety found the achievement worth a six-page spread late last summer. As the first documentary filmmaker to earn $1 billion in worldwide ticket sales, giant-screen film producer/director Greg MacGillivray joined an elite club—approximately 100 filmmakers—who have attained this level of success. Daily Variety’s Iain Blair writes, “The film business is full of showy sprinters: filmmakers and movies that flash by as they ring up impressive box office numbers, only to leave little of substance in their wake. Then there are the dedicated long-distance specialists, like Greg MacGillivray, whose thought-provoking documentaries —including EVEREST, TO THE ARCTIC, TO FLY! and THE LIVING Sea—play for years, even decades at a time. -

Divx Na Cd Strona 1

Divx na cd 0000 0000 Original title/Tytul oryginalny 0000 Polish CD//Subt/Nap title/Tytul polski isy 10ThingsIHateAboutYou(1999) Zakochana zlosnica 1/pl 1492: Conquest of Paradise (AKA 1492: Odkrycie raju / 1492: Christophe1492:Wyprawa Colomb do / raju1492: La conquête du paradis / 1492: La conquista del paraíso) (1992) 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003) Za szybcy za wsciekli 1/pl 2046(2004) 2046 . 2/pl 21Grams (2003) 21 Gram 2/pl 25th Hour(2002) 25 godzina 2/pl 3000Miles toGraceland(2001) 3000 mil do Graceland 1/pl 50FirstDates(2004) 50 pierwszych randek 1/pl 54(1998) Klub 54 AboutSchmidt(2002) About Schmidt 2/pl Abrelosojos(AKA Open Your Eyes) (1997) Otworz oczy 1/pl Adaptation (2002) Adaptacja 2/pl Alfie(2004) Alfie 2/pl Ali(2001) Ali Alien3 (1992) Obcy 3 AlienResurrection (1997) 4 Obcy 4 – Przebudzenie Obcy 2 – Decydujace Aliens (1986) 2 starcie Alienvs. Predator(AKA Alienversus Predator/ AvP) (2004) Obcy Kontra Predator Amelia/ Fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain, Le (AKA Amelie from AmeliaMontmartre / Amelie of Montmartre / Fabelhafte Welt der Amelie, Die / Fabulous Destiny of Amelie Poulain / Amelie) (2001) AmericanBeauty(1999) American Beauty AmericanPsycho(2000) American Psycho Anaconda(1997) Anakonda AngelHeart (1987) Harry Angel AngerManagement(2003) Dwoch gniewnych ludzi Animal Farm (1999) Folwark zwierzecy Animatrix, The(2003) Animatrix AntwoneFisher(2002) Antwone Fisher Apocalypse Now(AKA Apocalypse Now: Redux(2001)) (1979) DirApokalipsa cut Aragami(2003) Aragami Atame(AKA Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!) (1990) Zwiaz mnie Avalanche(AKA Nature