Purpose-Driven Consumption Building the Dialogue Between Companies and Consumers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEM Subjects Face the Haptic Generation: the Ischolar Tesis

STEM Subjects Face the Haptic Generation: The iScholar Tesis doctoral Nuria Llobregat Gómez Director Dr. D. Luis Manuel Sánchez Ruiz Valencia, noviembre 2019 A mi Madre, a mi Padre (†), a mis Yayos (†), y a mi Hija, sin cuya existencia esto no hubiese podido suceder. Contents Abstract. English Version Resumen. Spanish Version Resum. Valencian Version Acknowledgements Introduction_____________________________________________________________________ 7 Outsight ____________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Insight ______________________________________________________________________________________14 Statement of the Research Questions __________________________________________________________ 15 Dissertation Structure ________________________________________________________________________16 SECTION A. State of the Art. The Drivers ____________________________________________ 19 Chapter 1: Haptic Device Irruption 1.1 Science or Fiction? Some Historical Facts ______________________________________________ 25 1.2 The Irruptive Perspective ___________________________________________________________ 29 1.2.1 i_Learn & i_Different ____________________________________________________________________ 29 1.2.2 Corporate Discourse and Education ________________________________________________________ 31 1.2.3 Size & Portability Impact _________________________________________________________________ 33 First Devices _____________________________________________________________________________ 33 Pro Models -

Generation Alpha: Marketing Or Science?1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Acta Technologica Dubnicae volume 7, 2017, issue 1 DOI: 10.1515/atd-2017-0007 Generation Alpha: Marketing or Science?1 Ádám Nagy – Attila Kölcsey Received: September 17, 2016; received in revised form: March 8, 2017; accepted: March 9, 2017 Abstract: Introduction: The transition from the limited information environment to the extended information world has fundamentally transformed the communication and information-gathering processes. The new learning spheres (non-formal and informal learning, i.e. lifelong learning) require rethinking learning strategies. Purpose: The generation logic and knowledge of different generations can help making the learning process more effective and efficient. It also helps, if we know which generation exists and which one is a “fictious generation”. According to theory of Mannheim and the model of Prensky, we can describe Generation X, Y and Z, but now the name of the next generation is being established. Methods: With the help of traditional desk research, such as literature search, data mining and web search, this article covers the origin of Generation Alpha (Alfa), the possible characteristics attributed to this age group, and tries to discern if this concept is meaningful in terms of the generation paradigm. Conclusions: Overall, it is apparent that while the existence of X, Y, and Z generations is demonstrable, the naming and characterizing the Alfa generation is important for marketing purposes, scientifically there is no evidence for “Generation Alpha”. Key words: generations, GenAlfa, Alpha generation. Ádám Nagy, Pallasz Athéné University, Kecskemét, Hungary; J. -

Read an Extract

Prologue I have one of the best jobs in the world. I’m a social researcher, which basically means I study human behaviour. This involves observing different trends and their impact on how people behave, work, live, shop and communicate. The types of trends I focus on are often: technology trends – like the rise of artificial intelligence and robotics. Demographic shifts – like an ageing and more culturally diverse population. And one of my favourites, social trends – like understanding the mix of generations in our society. The year 2020 will go down in history as one of massive change, because COVID-19 accelerated and highlighted many of these trends. But even prior to 2020, I began to notice an increase in the interest the world was taking in the next generation of children. To many people, they are a bit of a mystery. As a result, I regularly get to speak to groups of parents wanting to find out more about the world shaping their children, educators, and business leaders wanting to better understand them, and some 1 Generation Alpha_368_Press Proofs_3.indd 1 22/3/21 12:04 pm GENERATION ALPHA of the leading technology platforms about what they need to know in order to remain relevant. What I have noticed is that people are starting to sit up and take note that a new generation is not only coming, but they are already here. This is precisely why I decided to write this book, along with Ashley Fell, the Director of Advisory at my research and communications company McCrindle. Between us, we have been in social research for almost three decades. -

The Network Generation Sleep&Eat Virtual 2020

InsideO The Network Generation Sleep&Eat Virtual 2020 Out The Network Generation InsideOut “Networking is not just about connecting people. It’s about connecting people with people, people with ideas, and people with opportunities. Our approach to this virtual networking lounge focuses on an experiential journey as a key factor to the success of this space typology. Weaving a delicate yet exciting networking experience for future generations, be it for business or pleasure, will create a balance of opportunity.” Sleep&Eat Virtual 2020 2 3 Generation Types InsideOut Generation X - 1965 to 1980 Generation Y - 1981 to 1995 Generation Z - 1996 to 2010 A global survey covering the three generations X, Y & Z was undertaken to further our understanding of what networking means to each generation. Here we highlight some of the likley drivers defining the character of these generation types. This generational research informed the underlying approach and concept for our Sleep & Eat Virtual Networking Lounge. Gene erations 4 5 Generation X InsideOut 1965 to 1980 Generation X’ers are the demographic between the boomers and the millennial’s, having been born between 1965 and 1980, a period during the post war reconstruction of Europe. Their life has not been easy. Following a period of upheaval, finding a job was a great challenge. To work and produce was their philosophy in life, leaving little room for idealism. Individualism and ambition, an addiction to work, or being a workaholic, were the values with which they grew up. Members of Generation X are known to be more resistant towards current trends, however, they support altruistic values of companies. -

Gen Z in the Workforce: Nuance and Success

GEN Z IN THE WORKFORCE: NUANCE AND SUCCESS Zachary N. Clark Dr. Kathleen Howley Director of Student Activities & Assessment Deputy Vice Chancellor for Academic & Student Affairs Indiana University of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education Overview In this session, you will: Acquire an overview of the different generations of Americans currently serving in the workforce, including Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z. Explore key differences and similarities in these generations across core belief structures, including understandings of society, education, leadership, technology, and more. Identify recommendations and best practices, reinforced with research, to help find success in the multigenerational workplace, including in the first post-educational work experience. Evaluate through deep reflection how participants define student success, while also collaborating with peers to identify ‘one piece of advice’ for trustees and presidents to ensure worthwhile experiences at our universities and to support post-graduation success. Things to Keep in Mind Generational studies are not exact, and have clear limitations. These pieces of information highlight national trends, as shown in sociological and educational research. Not every member of a particular generation of college student will be a cookie-cutter image to their peers. While engaging in discussion today, keep statements broad enough so as to respect the privacy and guard the identities of individuals (students, faculty, staff, administrators, -

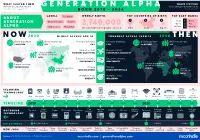

Generation Alpha Infographic 2021

WHAT SHAPED THEM THEIR FUTURE Millennial parents (Generation Y) GENERATION ALPHA Older siblings to Generation Beta Born 1980-1994 — aged 27-41 BORN 2010 2024 Born 2025-2039 LABELS WEEKLY BIRTHS TOP COUNTRIES OF BIRTH TOP BABY NAMES ABOUT The Alphas 1 2 3 Oliver 1 Charlotte GENERATION Generation glass Upagers 2,740,000 Noah 2 Amelia ALPHA William 3 Olivia Multi-modals Global Gen Generation Alphas born globally each week India China Nigeria CHARACTERISTICS Global Digital Social Mobile Visual α 11% WORKFORCE OF 2030 X 23% Y 32% Z 34% INCOMING TECHNOLOGY GoPro 3D Apple Tesla Smart Autonomous Quantum Aerial iPad Instagram Siri HERO3 printers Google glass watch Powerwall Fortnite speakers AirPods 5G Biometrics vehicles computing ridesharing TIMELINE 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 Street Fax Landline Car key - Desktop Credit Analogue OUTGOING Myspace directory Pager MP3 player Blackberry machine phone CD/DVD GPS unit ignition Textbooks computer cards Wallet watch TECHNOLOGY MILESTONES First Alphas born 500 million 1 billion 1.6 billion 2.2 billion Cybersecurity UX Drone Blockchain Data Virtual reality Robotics Sleep Sustainability Driverless Wellbeing AI Life Urban Space tourism NEW JOBS specialist manager pilot developer designer engineer mechanic technician officer train operator manager specialist simplifier farmer agent Source: UN, OECD, McCrindle | McCrindle 2021 mccrindle.com | generationalpha.com Iconic Music Leadership Screen Generation toys devices styles content L Roller skates Record player -

Embodied Learning of Dance by Genz and the Alphas As a Shift in Traditional Dance Education

Embodied Learning of Dance by GenZ and the Alphas as a Shift in Traditional Dance Education Maria Lucina Anonas De Santos, De La Salle–College of Saint Benilde, Philippines The Asian Conference on Education & International Development 2021 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The learning of a craft such as classical ballet, which requires mindful, cognitive, and physical coordination at the onset, runs contrary to the existing capabilities of GenZ (ages 10- 24) and the Alphas (ages 0-9), who are now the current students in the studio. Impacted by technology, their inherent urge to constantly experiment and communicate at a frenetic pace pose challenges in lesson retention, especially in a conventional setting as a dance studio, where the mode of teaching is strictly transmissional. This paper investigated the efficacy of adapting a traditional instructional method in today’s dance classroom. To develop an analytical understanding of movements, worksheets were tailor made to reinforce the lessons of weekly ballet classes. Anchored on studies that support the skills of coloring, tracing, and writing as means to create neural pathways to the brain, worksheets were devised to visually simplify foundational movement concepts, as well as to enhance focus and concentration. Findings indicated that learning objectives were reached in a shorter amount of time, which allowed the dance teacher to seamlessly progress into more advanced lessons, quicker. The shift from disembodied learning to embodied learning changed the relationship between the dance teacher and the student. No longer did the learning of dance remain simply transmissional, or a form of mimicry, from a linear teacher to student stimulus response model. -

Generation Alpha: Marketing Or Science?1

Acta Technologica Dubnicae volume 7, 2017, issue 1 DOI: 10.1515/atd-2017-0007 Generation Alpha: Marketing or Science?1 Ádám Nagy – Attila Kölcsey Received: September 17, 2016; received in revised form: March 8, 2017; accepted: March 9, 2017 Abstract: Introduction: The transition from the limited information environment to the extended information world has fundamentally transformed the communication and information-gathering processes. The new learning spheres (non-formal and informal learning, i.e. lifelong learning) require rethinking learning strategies. Purpose: The generation logic and knowledge of different generations can help making the learning process more effective and efficient. It also helps, if we know which generation exists and which one is a “fictious generation”. According to theory of Mannheim and the model of Prensky, we can describe Generation X, Y and Z, but now the name of the next generation is being established. Methods: With the help of traditional desk research, such as literature search, data mining and web search, this article covers the origin of Generation Alpha (Alfa), the possible characteristics attributed to this age group, and tries to discern if this concept is meaningful in terms of the generation paradigm. Conclusions: Overall, it is apparent that while the existence of X, Y, and Z generations is demonstrable, the naming and characterizing the Alfa generation is important for marketing purposes, scientifically there is no evidence for “Generation Alpha”. Key words: generations, GenAlfa, Alpha generation. Ádám Nagy, Pallasz Athéné University, Kecskemét, Hungary; J. Selye University, Komárno, Slovakia; [email protected] Attila Kölcsey, Excenter Research Centre, Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] 1 This article is supported by Bolyai Research Fellowship 107 Acta Technologica Dubnicae volume 7, 2017, issue 1 1 Introduction According to Mannheim, an age group can be considered a generation if they share some immanent attributes, generational consciousness or communal characteristics. -

Gen Alpha 2020

WHAT SHAPED THEM THEIR FUTURE Millennial parents (Generation Y) GENERATION ALPHA Older siblings to Generation Beta Born 1980-1994 — aged 26-40 BORN 2010 2024 Born 2025-2039 LABELS WEEKLY BIRTHS TOP COUNTRIES OF BIRTH TOP BABY NAMES ABOUT The Alphas 1 2 3 GENERATION Generation glass Upagers Noah 1 Olivia 2,740,000 Oliver 2 Ava ALPHA William 3 Amelia Multi-modals Global Gen Generation Alphas born globally each week India China Nigeria NOW2020 OLDEST ALPHAS ARE 10 YOUNGEST ALPHAS TURN 25 2050 THEN Global population Global median age University graduates University graduates Global population Global median age 7.8 BILLION 30.9 1 IN 3 1 IN 2 9.8 BILLION 36.1 Business context Business context Largest population FREQUENT DISRUPTION CONTINUOUS VOLATILITY Largest economy growth by continent CHINA ASIA Education outcomes Education outcomes EMPLOYABILITY ADAPTABILITY Largest economy Largest population growth by continent UNITED STATES Training Training Largest population AFRICA Largest CHINA QUALIFICATIONS MICROCREDENTIALS population INDIA Workplace focus Workplace focus DIVERSITY WELLBEING INCOMING TECHNOLOGY Autonomous Quantum Aerial iPad Instagram GoPro 3D Google glass Apple Tesla Smart Siri HERO3 printers watch Powerwall Fortnite speakers AirPods 5G Biometrics vehicles computing ridesharing TIMELINE 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 Street Fax Landline Car key - Desktop Credit Analogue OUTGOING Myspace directory Pager MP3 player Blackberry machine phone CD/DVD GPS unit ignition Textbooks computer cards -

Generational Insights to Inform Future Strategies Towards 2030

Analyse Australia Understanding the Future Consumer Generational insights to inform future strategies towards 2030 August 2020 The changing consumer landscape 04 Generation Alpha 06 Table of Generation Z 10 Generation Y 14 contents Generation X 18 Towards 2050 26 The Global outlook of the future 28 What does this mean for leaders? 30 Understanding the Future Consumer report is produced by: How can we help 32 McCrindle Research Pty Ltd Suite 105, 29 Solent Circuit Norwest NSW 2153 AUSTRALIA mccrindle.com.au [email protected] +61 2 8824 3422 Authors: Mark McCrindle, Ashley Fell, Kevin Leung, Peter Chi Data visualisation and design: Hendrik Zuidersma Title: Understanding the Future Consumer Publisher: McCrindle Research - mccrindle.com.au URL: analyseaustralia.com ISBN: 978-0-6486695-6-2 © McCrindle Research Pty Ltd 2020 This report is copyright. Fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review is permitted under the Copyright Act. In addition, the Publisher grants permission to use images and content from this report for commercial and non-commercial purposes provided proper attribution is given such as ‘Understanding the Future Consumer’ By Mark McCrindle, Ashley Fell, Kevin Leung, Peter Chi, is used by permission, McCrindle Research. 02 Understanding the Future Consumer Understanding the Future Consumer 03 Case study In 1996 the Eastman Kodak Company recorded one of their best years with a valuation of $30 billion USD, and revenues of $16 billion USD. Yet 16 years later it filed for bankruptcy. In 1888, founder George Eastman put the first model of Kodak camera to market. His proposition? “You press the 1996 Kodak valued at button, we do the rest.” He created the first technological wave of handheld cameras. -

2018 06 10 01 01Gn1006stgeneration Next AL 1

Sunday Times Combined Metros 1 - 2018/06/18 01:42:16 PM - Plate: SOUTH AFRICA’S YOUTH SURVEY REVEALING THE BRAND PREFERENCES OF KIDS, TEENS AND YOUNG ADULTS. Sunday Times Combined Metros 6 - 2018/06/18 01:46:32 PM - Plate: 6 2018 Make the Con nection Eye on new generations Sustai nabi l ity Going beyond Youth have M i l len n ials future in m i nd It’s important to future-proof brands By PALESA VUYOLWETHU TS HANDU for new consumers, writes Alf James ● Abouttwo yearsago clothingre- tailer Woolworths launched its rands need to mimic consumers and may not buy into #AreYouWithUs campaign with US human relationships mass consumerism as we know it. artist Pharrell Williams that aimed with their consumers. “Not many brands have really at making sustainability part of the Instant gratification, developed an understanding of Picture: 123RF conversation with their younger hyper - personalisation , generation z and generation alpha customers. The retailer spent mil- and technology as a and who their future consumer is, power, which brands should look lions influencing popular narrative Bmeans to utilise or a value-add will because their focus is on seriously at utilising.” that Going Green and making con- determine the brands that understanding who the millennials Van Loggerenberg contends that scious decisions on their purchas- generation alpha will choose to are and what makes them tick. an understanding of the way in ing habits, was in fact the right engage with, according to “However, they need to look at which technology is going to propel thing to do. -

The Effects of Generational Demographics on Information Management

THE EFFECTS OF GENERATIONAL DEMOGRAPHICS ON INFORMATION MANAGEMENT Major A.K. MacPherson JCSP 38 PCEMI 38 Master of Defence Studies Maîtrise en études de la défense Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2012 ministre de la Défense nationale, 2012. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE - COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 38 - PCEMI 38 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES RESEARCH PROJECT The Effects of Generational Demographics on Information Management By Major A.K. MacPherson This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces canadiennes fulfilment of one of the requirements of the pour satisfaire à l'une des exigences du Course of Studies. The paper is a scholastic cours. L'étude est un document qui se document, and thus contains facts and rapporte au cours et contient donc des faits opinions, which the author alone considered et des opinions que seul l'auteur considère appropriate and correct for the subject. It appropriés et convenables au sujet. Elle ne does not necessarily reflect the policy or the reflète pas nécessairement la politique ou opinion of any agency, including the l'opinion d'un organisme quelconque, y Government of Canada and the Canadian compris le gouvernement du Canada et le Department of National Defence.