How Visibly Different Children Respond to Story-Creation Deandria Frazier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes

“Come on along, you can’t go wrong Kicking the clouds away!” Broadway was booming in the 1920s with the energy of youth and new ideas roaring across the nation. In New York City, immigrants such as George Gershwin were infusing American music with their own indigenous traditions. The melting pot was cooking up a completely new sound and jazz was a key ingredient. At the time, radio and the phonograph weren’t widely available; sheet music and live performances remained the popular ways to enjoy the latest hits. In fact, New York City’s Tin Pan Alley was overflowing with "song pluggers" like George Gershwin who demonstrated new tunes to promote the sale of sheet music. George and his brother Ira Gershwin composed music and lyrics for the 1927 Broadway musical Funny Face. It was the second musical they had written as a vehicle for Fred and Adele Astaire. As such, Funny Face enabled the tap-dancing duo to feature new and well-loved routines. During a number entitled “High Hat,” Fred sported evening clothes and a top hat while tapping in front of an enormous male chorus. The image of Fred during that song became iconic and versions of the routine appeared in later years. The unforgettable score featured such gems as “’S Wonderful,” “My One And Only,” “He Loves and She Loves,” and “The Babbitt and the Bromide.” The plot concerned a girl named Frankie (Adele Astaire), who persuaded her boyfriend Peter (Allen Kearns) to help retrieve her stolen diary from Jimmie Reeve (Fred Astaire). However, Peter pilfered a piece of jewelry and a wild chase ensued. -

Sanur Price List 2020

Sanur Price List 2020 Diving Prices (IDR) 2 day-dives 1.800.000 3 day-dives 2.250.000 Trip supplements (per person/day): Tulamben - Amed - Padang Bai 140.000 /day Candidasa 540.000 /day Nusa Penida/Nusa Lembongan 610.000 /day All diving includes: transport from and to your hotel in Sanur/Kuta/Seminyak, tanks and weights, lunch, boat and porter fees, unlimited coffee, tea and water. Diving Discounts (not on supplements) 3 Days Diving 5% Discount 5 Days Diving 10% Discount 7 Day Diving 10% Discount & FREE Afternoon dive 10+ Days Diving 15% Discount Equipment rental Full set - reg, BCD, wetsuit, mask, booties, fins 150.000/day Dive computer 100.000/day Please ask reception for more prices for individual items Nitrox 85.000 /tank 15l tanks 80.000 /tank 15l Nitrox 90.000 /tank Private dive guide (subject to availability) 250.000/day Dive with an Instructor (subject to availability) 350.000/day Sanur Price List 2020 Non diving activities Prices (IDR) Snorkeling (incl equipment, subject to availability) Amed/Tulamben (excl. guide) Padang Bai (excl. guide) 980.000/day Join day-trip (subject to availability) Amed/Tulamben 250,000/day Padang Bai 300,000/day Day-trip with private driver – max 4 pax per car Ask for prices Misc Hotel pick-up outside Sanur/Kuta/Seminyak Ask for prices Airport transfer – to/from Sanur, Kuta or Seminyak, 1 way 300.000 /car Amed transfer – from Sanur, 1 way 650.000 /car Out of hours transfer supplement– After 9pm 50.000 /car Nusa Lembongan boat transfer – 1 way 300.000 pp Boat transfer includes pick-up and drop off at your hotel Return 500.000 pp Sanur Price List 2020 Courses Prices (IDR) Discover Diving PADI Discover Scuba Diving (2 dives) 2.300.000 Choose from: Amed, Tulamben or Padang Bai PADI Scuba Review (pool) 300.000 Entry-Level Courses PADI Scuba Diver (2days) 4.000.000 PADI Open Water Diver Course (4 days) 7.500.000 Staying longer? If you take the OW Course then you will get 10% off your Advanced Open Water Course. -

Counter-Insurgency Vs. Counter-Terrorism in Mindanao

THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTER-INSURGENCY VS. COUNTER-TERRORISM IN MINDANAO Asia Report N°152 – 14 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ISLANDS, FACTIONS AND ALLIANCES ................................................................ 3 III. AHJAG: A MECHANISM THAT WORKED .......................................................... 10 IV. BALIKATAN AND OPLAN ULTIMATUM............................................................. 12 A. EARLY SUCCESSES..............................................................................................................12 B. BREAKDOWN ......................................................................................................................14 C. THE APRIL WAR .................................................................................................................15 V. COLLUSION AND COOPERATION ....................................................................... 16 A. THE AL-BARKA INCIDENT: JUNE 2007................................................................................17 B. THE IPIL INCIDENT: FEBRUARY 2008 ..................................................................................18 C. THE MANY DEATHS OF DULMATIN......................................................................................18 D. THE GEOGRAPHICAL REACH OF TERRORISM IN MINDANAO ................................................19 -

99 Stat. 288 Public Law 99-86—Aug. 9, 1985

99 STAT. 288 PUBLIC LAW 99-86—AUG. 9, 1985 Public Law 99-86 99th Congress Joint Resolution To provide that a special gold medal honoring George Gershwin be presented to his Aug. 9, li>a5 sister, Frances Gershwin Godowsky, and a special gold medal honoring Ira Gersh- [H.J. Res. 251] win be presented to his widow, Leonore Gershwin, and to provide for the production of bronze duplicates of such medals for sale to the public. Whereas George and Ira Gershwin, individually and jointly, created music which is undeniably American and which is internationally admired; Whereas George Gershwin composed works acclaimed both as classi cal music and as popular music, including "Rhapsody in Blue", "An American in Paris", "Concerto in F", and "Three Preludes for Piano"; Whereas Ira Gershwin won a Pulitzer Prize for the lyrics for "Of Thee I Sing", the first lyricist ever to receive such prize; Whereas Ira Gershwin composed the lyrics for major Broadway productions, including "A Star is Born", "Lady in the Dark", "The Barkleys of Broadway", and for hit songs, including "I Can't Get Started", "Long Ago and Far Away", and "The Man That Got Away"; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to compose the music and lyrics for major Broadway productions, including "Lady Be Good", "Of Thee I Sing", "Strike Up the Band", "Oh Kay!", and "Funny Face"; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to produce the opera "Porgy and Bess" and the 50th anniversary of its first perform ance will occur during 1985; Whereas George and Ira Gershwin collaborated to compose -

Katalog 2012

støedomoøí amerika KDE NÁS NAJDETE Albánie ........................................................... 9 Argentina ..................................................41, 42 Alžírsko ........................................................... 6 Bolívie ......................................... 39, 40, 41, 42 Egypt ............................................................... 7 Brazílie .....................................................41, 42 Izrael ................................................................ 7 Ekvádor .......................................................... 39 Jordánsko .....................................................7, 8 Guatemala ............................................... 36, 37 Libanon .......................................................... 8 Honduras ................................................. 36, 37 Maroko .......................................................... 6 Chile ........................................................41, 42 Portugalsko ................................................... 11 Kolumbie .......................................................38 Sýrie ................................................................ 8 Kostarika ........................................................37 Španělsko ........................................................ 9 Kuba .............................................................. 34 Turecko .............................................. 13, 32, 49 Mexiko .....................................................35, 36 Nikaragua ..................... -

Mathis-Bali-Tours-2020-En.Pdf

Visit Taman Ayun temple built in the mid-seventeenth century by the royal family of Mengwi. Stop-over at the traditional market of Bedugul then drive to the temple Ulun Danu, located on the Lake Bratan, dedicated to the goddess of waters. Walk around Lake Tamblingan. Ability to walk through the primary forest of Tamblingan with return via the lake, on a raft (optional). Your next desination is Jatiluwih. Walk through this fabulous landscape and its splendid terraced rice field. It is one of the most beautiful valley of Bali. Visit the temple Gunung Kawi, in Tampak Siring and the temple of the sacred springs of Titra Empul. Continue onto the Kintamani village with a spectacular view on the lake and volcano of Mt Batur. Lunch in a local warung, on the edge of the Tegallalang rice fields. We then head to Tegallalang to admire its superb rice fields terrace. If required, you will have the possibility to do a short walk through the rice fields with your guide. During this day-tour, you will have the rare opportunity to meet a Balinese family. In the morning, you will drive past the the village and the school and you will then be invited to dine in the homestay. During the afternoon, you will have a choice to either prepare some offerings, cook with the ‘maîtresse de maison’ or learn how to play the Gamelan. Emotional day guaranteed with this unique excursion in the heard of Bali. Visit the old Klungkung temple of justice and its pavilions on the water. Then onto the Mother Temple of Besakih, with mount Agung in the backdrop. -

Vilondo's Guide to Diving Bali and the Surrounding Islands

VILONDO’S GUIDE TO DIVING BALI AND THE SURROUNDING ISLANDS. BOOK CONTENTS About the Authors i Diving Bali 1 Diving Bali at a glance 3 Map of Bali’s Dive sites 4 Nusa Dua 5 Nusa Lembongan and Nusa Penida 8 Amuk Bay – Padang Bai to Candidasa 11 Gili Islands 14 Amed to Gili Selang 17 Tulamben 20 Pemuteran 23 Menjangan Island 26 Gilimanuk Bay – Secret Bay 29 Dive Operators In Bali And Around 32 i about the AUTHORs STEFAN RUSSEL mads rode This book is written by Mads Rode and Stefan Russel. We Balinese waters is extremely varied and within short are both keen divers and spend a lot of time in Bali, distances you can get very different scuba diving experi- where we rent out luxury villas through our villa rental ences. company Vilondo. In addition to that, we write about travel-related topics on our online Bali travel guide. Just one last note: This is a free E-book and that is the way we like to keep it. If you come across someone Originally we created this book with our divehappy charging money for it, please let us know, but feel free to customers in mind, but soon decided to make it share the book and spread the word. If you have any available to everyone, as we found it hard to find a questions, you are always welcome to contact us good free guide to all the wonderful diving Bali has to through our website www.vilondo.com. offer. We hope this will inspire you to come and explore the We both share a passion for Bali and the beautiful underwater world around Bali and we wish you a good islands, unique culture and diverse landscapes. -

2013 Annual Report Coral Current - 2013 Annual Report 3 New Trends

CURRENT CORALCORAL REEF ALLIANCE 2013 ANNUAL REPORT CORAL.ORG PASSIONA TE PEOPLE DR. MICHAEL WEBSTER, they can benefit socially, culturally, and And it is this constituency that helps us JIM TOLONEN, my visit with the people who are working welcomed five Board members who EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR economically from preserving their reef address threats like water pollution and BOARD CHAIR tirelessly to ensure healthy reefs in bring new expertise and ideas to the is crucial for conservation to succeed in overfishing, and strengthen how reefs Honduras: the CORAL team of Jenny organization and are helping to craft a This past fall when our In 2013, I visited one of the long term. are managed, leading to measurably Myton and Pamela Ortega, our col- renewed organizational strategic plan. field staff arrived from our field sites—Roatan, healthier reef ecosystems. leagues at the Roatan Marine Park, We also launched the CORAL Interna- around the world to Honduras—with other Our work is driven by diplomacy, AMATELA, BICA, and Healthy Reefs tional Council. In their first order of participate in our members of the Board passion, and perseverance as we While we exist to save reefs, our work is Initiative, even the dive shop owners, business, the growing group of CORAL annual organizational planning session, and staff. I had the opportunity to see strategize and collaborate with a wide all about people. I am honored to give restaurateurs, and hotel staff. With advisors collectively committed to raise I was struck—again—by how talented, firsthand how our work is helping save variety of stakeholders, and act as a you the chance to hear directly from the leadership of these individuals and $100,000 and use it as a challenge to dedicated, and passionate they are. -

BA9201-60 This Is Your Balinese Paradise Amed, Bali

BA9201-60 This is Your Balinese Paradise Amed, Bali Soak Up the Tranquility of Amed, Bali for Eight Days & Seven Nights at Villa Pantai for Up to Eight People, Including Scuba Diving Lessons, Balinese Massages and Your Choice of a Tour of Tirta Gangga Water Palace or the Lempuyang Temple (Land Only) Set on the north-eastern tip of Bali, Amed is the perfect Indonesian getaway, with its peaceful essence and tropical flair, and a stay at the Villa Pantai is sure to be memorable. As you explore the waters of Bali on your scuba dive session, you’ll see the exquisite varieties of underwater life; or let the soothing sounds of the ocean waves crashing lull you to a place of relaxation during your Balinese massages. A tour of the beautiful water palace of Tirta Gangga or the temple Pura Lempuyang round out your trip, but however you spend your days, you’ll see that Amed is Bali’s best-kept secret. Your accommodations at this private Bali villa are nothing short of amazing! Villa Pantai is a modern yet classic, elegant yet relaxed property, designed to allow you to escape the limits of time and immerse yourself in the most indulgent of experiences. Spectacular sunrises make the easternmost point of Bali shine. Enjoy them with a cup of tea early in the morning from the villa's balcony, and if you’re lucky, you’ll catch a glimpse of dolphins playing in the water, too! There is an unpretentious luxury in uncommonly beautiful surroundings, and the unique private Bali Villa rental is your perfect opportunity. -

Katalog 2011

støedomoøí amerika KDE NÁS NAJDETE Alžírsko ........................................................... 6 Argentina ....................................................... 35 Egypt ........................................................... 7, 8 Bolívie .................................................... 33, 35 Izrael ................................................................ 8 Ekvádor ......................................................... 32 Jordánsko ..................................................... 8, 9 Guatemala ............................................... 30, 31 Libanon ........................................................ 8, 9 Honduras ................................................. 30, 31 Libye ............................................................... 7 Chile .............................................................. 35 Madeira .......................................................... 9 Kostarika ....................................................... 31 Maroko ............................................................ 6 Kuba .............................................................. 28 Sýrie ................................................................ 9 Mexiko .......................................................... 30 Turecko ........................................................... 9 Nikaragua ...................... ............................... 31 Panama ......................................................... 31 Paraguay ....................................................... -

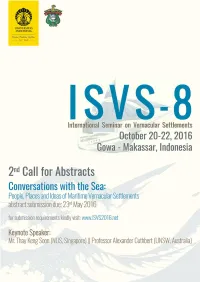

ISVS-8I Nternational

ABSTRACT COMPILATION I n t e r n a t i o n a l S e m i n a r o n V e r n a c u l a r ISVS-8Settlements 2016 Gowa Campus- Hasanuddin University, Makassar-INDONESIA, October 20th-22nd, 2016 International Seminar on Vernacular Settlements CONVERSATION WITH THE SEA:People, Place and Ideas of Maritime Vernacular Settlements October 20th–22nd, 2016, Gowa- Makassar, Indonesia Welcome to Makassar … We wish all participants will find this seminar intellectually beneficial as well as fascinating and looking forward to meeting you all again in future seminars ISVS-8 CONVERSATION WITH THE SEA People, Place and Ideas of Maritime Vernacular Settlements Seminar COMMITTEE Department of Architecture Hasanuddin University CONTENT Content ................................................................................................ i Seminar Schedule ................................................................................ vi Rundown Seminar ............................................................................. viii Parallel Session Schedule .................................................................... ix Abstract Compilation ........................................................................ xvii Theme: The Vernacular and the Idea of “Global” 1. Change in Vernacular Architecture of Goa: Influence of changing priorities from traditional sustainable culture to Global Tourism, by Barsha Amarendra and Amarendra Kumar Das ....................................... 1 2. Emper : Form, Function, And Meaning Of Terrace On Eretan Kulon Fisher -

“Fascinating Rhythm”—Fred and Adele Astaire; George Gershwin, Piano (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“Fascinating Rhythm”—Fred and Adele Astaire; George Gershwin, piano (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell George Gerswhin Fred Astaire Adele Astaire For an artist so synonymous with dance, Fred Astaire is also certainly associated with a wide selection of musical standards—“Cheek to Cheek,” “Top Hat,” “Funny Face” and “Night and Day,” to name just a few. And for a man forever partnered with Ginger Rogers within popular culture, Astaire got his first taste of stardom while still teamed with his talented elder sister and longtime stage co-star, Adele. Both natural-born dancers with unbelievable technique and an innate sense of rhythm, the Astaires began performing as a brother-sister team in vaudeville in the 1900’s. Eventually, they worked their way up to the Orpheum Circuit. Filling their act with songs, sibling teasing and, of course, dance, the duo first appeared on Broadway, in the show “Over the Top,” in 1917. Meanwhile, though the brothers Gershwin, George and Ira, were each having some individual success as Tin Pan Alley tunesmiths in the early 1920’s, they achieved their greatest success when they teamed up together for the Broadway stage and wrote the musical “Lady, Be Good” in 1924. Along with composing that show’s long-enduring title tune, the Gerswhins also wrote “Fascinating Rhythm,” a bouncy duet that Fred and Adele would perform in the show in New York and in London’s West End. They would commit it to record, on Columbia, with George Gerswhin on piano, in 1926. This recording was named to the Library of Congress’ National Registry in 2004.