Pdf, Accessed 15 December 2017]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

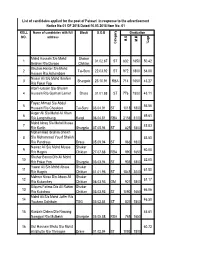

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %Age 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE

Selection List of candidates who have applied for admission to B. Ed Programme (Kargil Chapter) offered through Directorate of Admisssions, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age OM 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE, KARGIL KARGIL ST 9 7.09 78.78 2 1898735 SHAHAR BANOO MOHAMMAD BAQIR BAROO KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7.87 78.70 3 1895262 FARIDA BANOO MOHD HUSSAIN SHAKAR KARGIL ST 2400 1800 75.00 VILLAGE PASHKUM DISTRICT KARGIL, 4 1897102 HABIBULLAH MOHD BAQIR LADAKH. KARGIL ST 3000 2240 74.67 5 1894751 ANAYAT ALI MOHD SOLEH STICKCHEY CHOSKORE KARGIL ST 2400 1776 74.00 6 1898483 STANZIN SALTON TASHI SONAM R/O MULBEK TEHSIL SHARGOLE KARGIL ST 3000 2177 72.57 7 1892415 IZHAR HUSSAIN NIYAZ ALI TITICHUMIK BAROO POST OFFICE BAROO KARGIL ST 3600 2590 71.94 8 1897301 MOHD HASSAN HADIRE MOHD IBRAHIM HARDASS GRONJUK THANG KARGIL KARGIL ST 3100 2202 71.03 9 1896791 MOHD HUSSAIN GHULAM MOHD ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL KARGIL ST 4000 2835 70.88 10 1898160 MOHD HUSSAIN MOHD TOHA KHANGRAL,CHIKTAN,KARGIL KARGIL ST 3400 2394 70.41 11 1898257 MARZIA BANOO MOHD ALI R/O SAMRAH CHIKTAN KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7 70.00 12 1893813 ZAIBA BANOO KACHO TURAB SHAH YABGO GOMA KARGIL KARGIL ST 2100 1466 69.81 13 1894898 MEHMOOD MOHD ALI LANKERCHEY KARGIL ST 4000 2784 69.60 14 1894959 SAJAD HUSSAIN MOHD HASSAN ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL ST 3000 2071 69.03 15 1897813 IMRAN KHAN AHMAD KHAN CHOWKIAL DRASS KARGIL RBA 4650 3202 68.86 16 1897210 ARCHO HAKIMA SYED ALI SALISKOTE TSG KARGIL ST 500 340 68.00 17 -

S.No Name of the Block Name of the Beneficiary Complete Address With

District Kargil_JSSK Mother Beneficiary List (April-Sept)2016-17 S.No Name of Name of the Complete Husband's Name Name of the Date of Amo Account No Date the Block Beneficiary Address with Institution Delivery unt Telephone where delivery Paid Number , If took place. (Rs.) any 1 Chiktan Fatima Banoo 9469275121 Nizam DHK 25-04-16 1400 0683040100003360 2 Shargole Hakima Banoo 9469238929 Sajjad DHK 04-07-2016 1400 1219040100002445 3 Sankoo Khera banoo 9469625809 Ibrahim DHK 04-04-2016 1400 0203040100009042 4 Kargil Nargis Banoo Gh Mohd DHK 03-08-2016 1400 0096040100037135 5 Kargil Sayida Banoo 9469214849 Zulfqar ali DHK 04-06-2016 1400 0683040100002551 6 Kargil Tsering Choskit 9419553496 Stanzin Rabzang DHK 04-01-2016 1400 0349040100030505 7 Shargole Zahra Batool 9419847951 Nissar hussain DHK 04-11-2016 1400 0683040100003166 8 Shargole Zainab Bee 9419446150 Mohd hasan DHK 04-09-2016 1400 0683040100003310 9 Shargole Zakiya Banoo 9419502461 Stering Dorjay DHK 24-7-15 1400 0203040100003018 10 Drass Amina Parveen 9469389150 Mohd Suliman DHK 30-3-16 1400 0372040100023477 11 Sankoo Archo Zakiya Syed ali DHK 09-08-2016 1400 0203040100005570 12 Kargil Assiya Banoo 9469230822 Feroz Hussain DHK 26-3-16 1400 0096040100023028 13 Sankoo Fareeda Tabbasum Manzoor hussain DHK 04-05-2016 1400 0203040100009063 14 Sankoo Fatima Banoo 9419476728 Zaheer ahmad DHK 25-3-16 1400 0096040100025769 15 Kargil Fatima Banoo 9469661143 Mohd Ali DHK 18-4-16 1400 0096040100033220 16 TSg Fatima Banoo 9419310285 Mohd Gulzar DHK 04-11-2016 1400 0617040860000021 17 Kargil Fatima -

AAP BADP 2017-18 --Kargil District

AAP BADP 2017-18 --Kargil District Rs in Lacs Location Estimated Cost Commul Exp Funds releases as 1st Installment 2017- S.No Scheme/Works Revised AA upto ending Proposed Outlay 2017-18 District Block Village Distance Original AA Cost 18 Cost 03/2017 from LOC/LAC I KARGIL BLOCK CS SS Total CS SS Total R&B On-going Works 1 L/R to Poyen Bye Pass Kargil Kargil Poyen 6 125.00 200.00 164.74 1.80 0.20 2.00 1.38 0.15 1.53 2 L/R Karkith Badgam Kargil Kargil badgam 1 340.00 340.00 285.46 1.80 0.20 2.00 1.38 0.15 1.53 3 Circular Road from H/W to Power House Kargil Kargil Kargil 6 115.00 150.00 144.80 4.68 0.52 5.20 3.59 0.40 3.99 L/R to Karkithchoo from Badgam bridge transferred 4 Kargil Kargil Karkichu 10 95.00 95.00 88.53 5.76 0.64 6.40 4.42 0.49 4.91 from (DP to BADP for Compl). 5 L/R MES to GGS Tanmosa Kargil Kargil Kargil 7 57.00 105.00 80.36 5.40 0.60 6.00 4.14 0.46 4.60 6 Constt. Of L/R to Chumorik Barchay Kargil Kargil Barchay 4 60.00 60.00 47.72 5.84 0.65 6.49 4.48 0.50 4.98 7 Constt. Of Link Road Beamathang Kargil Kargil Baroo 8 90.00 90.00 64.15 5.40 0.60 6.00 4.14 0.46 4.60 Constt. -

List of Panchayat Ward Officer.Xlsx

Detail list of ward officers for Panchayat level in respect of Kargil District Name of Name of S.No Name of Panchayat Qualification Mobile No E‐mail ID Photograph Block VLW/MPW/GRS 1 Karchey Khar Mahmooda Khatoon, B.Sc 9419523218 2 Barsoo Mohd Ibrahim, GRS 10+2 9419832830 3 Tiket Nissar Hussain, GRS 10+2 8082513637 4 Bartoo Ghulam Raza, MPW 10th 9469235684 Haji Mohd Akber, 5 Nangma kousar 10th 7051621063 Work Sup. 6 Sangrah Zahid Hussain, VLW MA (B.Ed) 7051452136 7 Faroona Sakina Banoo, GRS 10th 9469266127 Toyiba Maqsooma, 8 Thassgam A 12th 9419312966 GRS 9 Thasgam B Sonam Dolma, GRS 10th 9469270775 10 Lankerchey A Mohd Baqir, GRS 8491814784 11 Stakpa Fatima Jenah,VLW 9419346602 12 Thang Dumbur Abdul Hussain, VLW 9906811949 13 Thang Dumbur‐A Abdul Hussain, VLW 9906811949 14 Thasgam Thuina‐B Sonam Dolma, GRS 9469270775 15 Umba Ghulam Haider, MPW 9419547534 16 Khawos Abuzar, GRS 9469737633 17 Kochik Gulzar Hussain, GRS 9419706132 18 Namsuru Ali Asgar,VLW 9469258174 19 Panikhar Zubida Akhtar, GRS 9469211736 Tai‐suru 20 Parkachik Mohd Ilyas, GRS 9469265553 mismaikazab 21 Purtikchay Mohd Ismail, GRS 9469046251 @gmail.com 22 Taisuru Ali Haider, GRS 9469733737 23 Tangole Monsoor Mehdi, GRS 9469280293 24 Youljuk Mohd Hussain, GRS 9419505546 25 Lochum Mohd Mussa, GRS 9469269400 26Lotchum Skamboo Marziya,GRS 9419934550 27 Tacha Haji Mohd Raza, MPW 9906712847 28 Karamba Mohd Qasim, VLW 9797947824 29 Mulbekh Stanzin Lhazais, GRS 9469210112 Shargole Namgyal Wangchok, 30 Shargole 9419304447 MPW 31 Wakha Gh. Mehdi, VLW 946929683 32 Pashkum‐A Sajid Hussain, -

Registration No

List of Socities registered with Registrar of Societies of Kashmir S.No Name of the society with address. Registration No. Year of Reg. ` 1. Tagore Memorial Library and reading Room, 1 1943 Pahalgam 2. Oriented Educational Society of Kashmir 2 1944 3. Bait-ul Masih Magarmal Bagh, Srinagar. 3 1944 4. The Managing Committee khalsa High School, 6 1945 Srinagar 5. Sri Sanatam Dharam Shital Nath Ashram Sabha , 7 1945 Srinagar. 6. The central Market State Holders Association 9 1945 Srinagar 7. Jagat Guru Sri Chand Mission Srinagar 10 1945 8. Devasthan Sabha Phalgam 11 1945 9. Kashmir Seva Sadan Society , Srinagar 12 1945 10. The Spiritual Assembly of the Bhair of Srinagar. 13 1946 11. Jammu and Kashmir State Guru Kula Trust and 14 1946 Managing Society Srinagar 12. The Jammu and Kashmir Transport union 17 1946 Srinagar, 13. Kashmir Olympic Association Srinagar 18 1950 14. The Radio Engineers Association Srinagar 19 1950 15. Paritsarthan Prabandhak Vibbag Samaj Sudir 20 1952 samiti Srinagar 16. Prem Sangeet Niketan, Srinagar 22 1955 17. Society for the Welfare of Women and Children 26 1956 Kana Kadal Sgr. 1 18. J&K Small Scale Industries Association sgr. 27 1956 19. Abhedananda Home Srinagar 28 1956 20. Pulaskar Sangeet Sadan Karam Nagar Srinagar 30 1957 21. Sangit Mahavidyalaya Wazir Bagh Srinagar 32 1957 22. Rattan Rani Hospital Sriangar. 34 1957 23. Anjuman Sharai Shiyan J&K Shariyatbad 35 1958 Budgam. 24. Idara Taraki Talim Itfal Shiya Srinagar 36 1958 25. The Tuberculosis association of J&K State 37 1958 Srinagar 26. Jamiat Ahli Hadis J&K Srinagar. -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 20, March 2006 CONTENTS Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 News from Ladakh: 6 News from Members 33 Expedition Report: Hanle Basin, Ladakh, by Richard V. Lee, Ritesh Ariya, Matthew V. Lee, Howard A. Lippes, Christopher Wahlfeld 34 Conference Report 12th Colloquium of the IALS at Kargil John Bray 40 Inauguration of the Munshi Bhatt Museum, Kargil Nazir Hussain and Jacqueline Fewkes 50 Yak tale: The Furness Yak Farmer, by Peter Anderson, Postscript by Henry Osmaston 51 Book reviews: Being a Buddhist Nun, by Kim Gutschow Henry Osmaston and John Crook 54 Recollections of Tibet, by Konchok Tharchin and Konchok Namgial Martin Mills 57 The Kingdom of Lo (Mustang), by Ramesh K. Dhungel John Bray 58 Birds and Mammals of Ladakh, by Otto Pfister Henry Osmaston 60 Thesis review Local Politics in the Suru Valley, by Nicola Grist Patrick Kaplanian 62 New books 64 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 16 68 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL Once again I must apologize for the long delay in bringing out this issue of Ladakh Studies. Many different factors have caused postponement of publication, including our wish to initiate discussions about the current state and future direction of the IALS and of the newsletter. Hon. Sec. John Bray’s letter on the next page takes up some of these issues. As I am about to embark on a sabbatical year during which I hope to be away from my office for extended periods of time, I believe the time is right to hand over editorial responsibility for Ladakh Studies to someone else. -

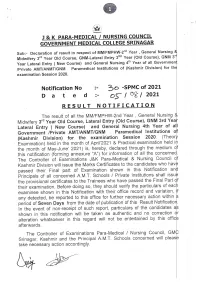

Declaration of Result in Respect of MM/FMPHW 2Nd Year , Gen Nursing and Midwifery 3Rd Year

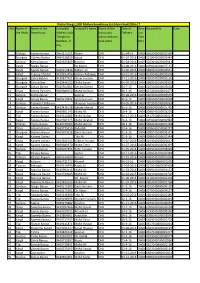

ANNEXURE TO RESULT NOTIFICATION NO:- 1 - SPMC OF 2021 EXAMINATION DATE :- -08- 2021 SESSION _'2020 Max. Marks RESU STREAM ROLL.NO NAME PARENTAGE RESIDENCE NAME OF THE INSTITUTE MM(T) MO (T) MM(P) MO (P) Marks Obt. LT FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85800 TAHIRA BANOO MOHD HUSSAIN SAMRAH GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 106 150 91 350 197 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85801 UMI-LEELA YOUNUS ALI HAGNIS GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 100 150 96 350 196 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85802 HAMIDA BANO MOHD ISSAQ TSAYTSAY THANG GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 138 150 95 350 233 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85803 ZULAIKHA BANOO MOHD IBRAHIM ANDOO GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 118 150 94 350 212 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85804 NARGIS BANOO FIDA ALI SKAMBOO GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 114 150 98 350 212 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85805 MARZIA BANOO ABDEY ZOHRA TUMAIL GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 122 150 98 350 220 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85806 HUSNIA BANOO MOHD HUSSAIN HUMBURTICK GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 102 150 95 350 197 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85807 LOBZANG CHOSZOM STANZIN JINBA SURLAY GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 148 150 100 350 248 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85808 STANZIN TSELAK LOTUS GYALSON PHEY GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 126 150 94 350 220 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85809 ZULIKHA BANOO MOHD SIDIQ GOSHAN GOVT. AMT SCHOOL KARGIL 200 132 150 99 350 231 Pass FMPHW - 2ND YR FW - II / 85810 SAKEENA BANOO MOHD HADI PURTIKCHAY GOVT. -

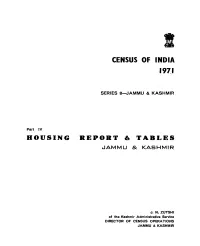

Housing Report & Tables, Part IV, Series-8

I CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES a-JAMMU & KASHMIR Part IV HOUSING REPORT .& TABLES L-1AMMU & KASHMIR J. N. ZUTSHI of the Kashmir Administrative Service DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS JAMMU & KASHMIR CONTENTS PatiND. Chapter I INTRODUCTION 1-8 Charter n USES OF CENSUS HOUSES 9-47 Usage Defined-Typical Houses Types-Distribution by Usage-1961-1971 Comparision-District wise-Analysis-Vacant Census Houses-Census Houses used as Residence-Shope-cum-residence Workshop-cum-residence-Hotels, Sarais, Dbaram-sbalas etc.-Shops excluding Eating Houses -Factories, Workshops and Worksheds-Business Houses and Offices~Restaurants, Sweet mt"at Shops and Eating Places-Places of Entertainment and Community Gathering-Places of Worship-Others-Srinagar and Jammu Cities-Functional Classification-1961-1971 Comparison of Occupied Census Houses-State, Districts and two Cities Chapter m MATERIAL OF WALL AND ROOF OF HOUSES . 48-66 Material of Wall-1961-1971 Comparison-State-Districts-Cities of Srinagar and Jammu -Slum-dwellings Material of roof-1961-1971 Comparison-State-Districts-Cities-Material of wall and Material of Roof Cross-classified . Chapter IV HOUSEHOLDS AND NUMBER OF ROOMS OCCUPIED . 67-75 Households Classified by Number of Rooms-State and its Districts-Cities of ·Srinagar and Jammu-Number of Persons per Household-State-Districts and Cities Chapter V TENURE STATUS 76-82 State-Districts of Kashmir Province-Districts of Jammu Province-Cities of Srinagar and Jammu A.PPENDICES Appendix I. Houselist and Establishment Schedules 84-87 Appendix II. Editing and Coding Instructions for Houselist 88-96 Appendix III. List of Snow-bound Areas 97-105 Appendix IV. Instructions to Enumerators for filling-up the Houselist and Establishment Schedules 106-119 Appendix V. -

![Pdf, Accessed 29 July 2019]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8568/pdf-accessed-29-july-2019-3928568.webp)

Pdf, Accessed 29 July 2019]

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sani-Tarungtse in Purig and Zanskar (Ladakh) Le bouddhisme avant la Première Diffusion ? Les cas de Tangol, Dras, Phikhar et Sani-Tarungtse au Purig et au Zanskar (Ladakh) Quentin Devers Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4226 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4226 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Quentin Devers, “Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sani- Tarungtse in Purig and Zanskar (Ladakh)”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/emscat/4226 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/emscat.4226 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sa... 1 Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sani-Tarungtse in Purig and Zanskar (Ladakh) Le bouddhisme avant la Première Diffusion ? Les cas de Tangol, Dras, Phikhar et Sani-Tarungtse au Purig et au Zanskar (Ladakh) Quentin Devers Introduction 1 The purpose of this paper is to introduce newly documented sites from Purig and Zanskar that offer a rare insight into an early phase of Buddhism in Ladakh of Central Asian or Kashmiri inspiration. The question of the introduction of Buddhism to Ladakh is usually tied to the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (Tib. -

District Census Handbook, Ladakh, Parts X-A & B, Series-8

CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A & B I TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY SERIES-8 VILLAGE & TOWNWISE JAMMU & KASHMIR PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT LADAKH DISTRICT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK J. N. ZUTSHI of the Kashmir Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir g ::: '" z 0 0 .., ~ I/) e Z ~ Ii . ~ ~ " l • • > l- i •o 0• i' ...0 .. ~ . ·% U ~ II.. ~ . ~ c 0 • W 0 cc: . .., o 0 o 0 ~ 0 N ~ . t- ;: U') Q tR tb • '" 0 N -0 ::? CENSUS OF INDIA 197I LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Central Government Publications-Census ofIndia 1971-Series 8-Jammu & Kashmir is being published in the following parts. Number Subject Covered Part I-A General Report Part I-B General Report Part I-C Subsidiary Tables Part II-A General Population Tables Published Part II-B Economic Tables Part II-C(i) Population by Mother Tongue, Religion, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part II-C(ii) Social & Cultural Tables & Fertility Tables Part III Establishments report & Tables Published Part IV Housing Report & Tables Published Part VI-A Town Directory Published Part VI-B Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns Part VI-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages Part VII I-A !Administration Report on ~numeration Published Part VIII-B tAdministration Report on Tabulation Part IX Census Atlas Part I X-A Administrative Atlas Miscellaneous (i) Study of Gujjars & Bakerwals (ii) Srinagar City DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOKS Part X-A Town & Village Directory Part X-B Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract Part X-C Analytical Report, Administrative Statistics & Uistrict Census Tables tNot for Sale "'District Census Handbooks of Doda, Srinagar, Anantnag, Udhampur, Jammu, Baramula, ;R.ajauri and Punch already published. -

Licence No Name of the Driver Receipt Details Vehicle Class NT

ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 27/02/2012 TO 24/12/2012 1 Sl No. Licence No Name of the Driver Date of Birth NT Val From -To SIGN OF AUTHORITY Date of Issue Son/Wife/Daughter of Qualification TR Val From -To Receipt Details Permanent Address Blood Group Vehicle Class Temporary Address & Sex Identification Mark 1 JK-0720120000786 MURTAZA 15/12/1980 11/04/2012 14/12/2030 05/09/2012 MOHD. HUSSAIN Post Graduation Rs.200 /AA-7162/ CHANGCHIK KARGIL LADAKH 194103 AB+ M MCWG LMV H. NO. 8, KHARDONG PASHKUM, KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A BLACK MOLE ON THE CHIN. 2 JK-0720120002264 SHEIKH MOHD. HUSSAIN 07/08/1963 29/03/2012 06/08/2013 29/03/2012 SHOOKOOR ALI HSC Rs. // SILMO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 Unknown M MCWG LMV SILMO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 3 JK-0720120002265 MOHD. HASSAN 05/04/1978 29/03/2012 04/04/2028 29/03/2012 ASGAR HSC Rs. // HARDASS KARGIL LADAKH 194103 B+ M MCWG LMV HARDASS KARGIL LADAKH 194103 4 JK-0720120002266 KUNCHOK NAMGAIL 02/06/1982 29/03/2012 28/03/2032 29/03/2012 TSERING PUNCHOK HSC Rs. // HENASKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 O+ M MCWG LMV HENASKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 S/W BY NATIONAL INFORMATICS CENTRE ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 27/02/2012 TO 24/12/2012 2 Sl No. Licence No Name of the Driver Date of Birth NT Val From -To SIGN OF AUTHORITY Date of Issue Son/Wife/Daughter of Qualification TR Val From -To Receipt Details Permanent Address Blood Group Vehicle Class Temporary Address & Sex Identification Mark 5 JK-0720120002267 MOHD.