Embroidered Relations in Kutch: Women, Stitching and the Third Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Karnataka in India Agamudaiyan in India Population: 2,974,000 Population: 888,000 World Popl: 2,974,000 World Popl: 906,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.51% Chr Adherents: 0.50% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan Nattaman -

Banni Grassland

Symposium on Banni Grassland Report of Symposium on Banni Grassland 4th & 5th March 2011 Symposium Sponsors Gujarat State Forest Department, GoG, Gandhinagar Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation, GoG, Gandhinagar Commissionerate of Rural Development, GoG, Gandhinagar Organized By Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE) Post Box # 83, Mundra Road Bhuj – 370 001, Kachchh, Gujarat, India Website: www.gujaratdesertecology.com Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE), Bhuj-Kachchh Symposium on Banni Grassland Background Banni region has a very fascinating history, geography, diversity of flora and fauna, highly nutritive grasses; rich cultural heritage of Maldhari (Cattle breeders) communities, unrivalled embroidery work and other handicrafts, soul-touching folk and Sufi music, earthquake resistant mud houses Bhunga, traditional fresh water reservoirs Virda, traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and animal breeding and last but never the least, drought tolerant highly productive livestock - the very base of survival of Maldharis. Banni is perhaps the only largest stretch (2617 km2) of grasslands in India, which was once the „finest grassland‟ of Asia. It is located between Kachchh mainland and Greater Rann of Kachchh in the north western part of Gujarat State of India. The region is believed to have formed due to seismic activities and marine processes operating in the north along with fluvial deposition by the Indus and other rivers during the Vedic times. These virtues of Banni have always attracted scientists, sociologists, naturalists and tourists. Livestock is the mainstay of inhabitants of Banni, constituting major bulk of their assets. Despite tough survival conditions, Banni buffaloes are the most productive cattle in India and are recently recognised by „National bureau of Animal Genetic Resources‟ as 11th distinct breed of the nation. -

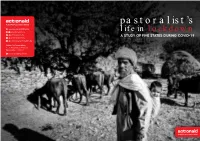

Pastoralist's Life in Lockdown

pastoralist’s www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia life in lockdown @actionaid_india A STUDY OF FIVE STATES DURING COVID-19 @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association, R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 2 3 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 First Published September, 2020 Some rights reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for non- commercial purposes under the same original license terms. Photograph Credits Anu Verma and Biren Nayak Edited by Joseph Mathai Layout by M V Rajeevan Cover Page by Nabajit Malakar Published by Natural Resources Knowledge Activist Hub www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia @actionaid_india @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 Printed at: Baba Printers, Bhubaneswar CONTENTS Foreword v Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Understanding pastoralism and pastoral occupation 3 Pastoral communities in India 7 Chapter 2: Impact of COVID-19 on Pastoralists: An Overview 11 Methodology 14 Chapter 3: Study Findings 17 Challenges in moving with herd during lockdown 17 Changes in time of migration 19 Mobility of pastoral communities during lockdown 22 Change in -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

The King's Last Fight

ZOOLOGY 76 The King’s last fight Once the realm of the Asiatic lion stretched from the Mediterranean to Central Asia. Today its habitat has shrunk to a small protected area in north-west India. Although it is thriving there, the species is not yet out of the woods PHOTOS: BRENT STIRTON/GETTY IMAGES BRENT STIRTON/GETTY PHOTOS: Words: Fabian von Poser Photography: Brent Stirton 77 78 ZOOLOGY At the beginning of the 20th century there were only a mere 20 to 40 lions. After that the population recovered slowly. The last census in 2010 revealed a population of 411 79 ZOOLOGY 80 From their ambush lions attack with lightning speed. The herdsmen of the region have learned to live with the losses, even if it hurts: a cow or a buffalo is worth 500 euros, a small fortune in India 81 ZOOLOGY N THE EARLY MORNING it is still cool Once the king of beasts ruled a vast territory that in Gir. Slowly the heat of the incipient day stretched from the Mediterranean to India. Just 150 I dissolves the fog in the treetops. The morning years ago the big cats crossed through the steppes sun illuminates the forest honey yellow. Against of the Middle East and Central Asia. But man’s the first light of day the teak trees appear as in a relentless hunting brought them to the edge of whimsical painting. It is quiet, only the shrill call extinction. In Turkey, the last lion was shot in 1870, of the peacocks penetrates the forest. At a water in Syria in 1895, in Iraq in 1918. -

Maldhari' and the Gir Prctected Area - Amufualinteraction

RJPSS 40, No.2,2015 3t 'Maldhari' and the Gir Prctected Area - Amufualinteraction 5 Dr. Rajeshwarsinh N Chudasama* Introduction: The most important human component ofthe Gir ecosystem has been the population ofresident 'Maldhari'. They are devoutly religious pastoral community who has been an integral part of Gir forest for generations. They are living in about 54 small settlements called 'Nesses' in the forest area with atotal human population of 2,540 and that of cattle about 9,820. They are physically robust, courageous and amiable persons. They live on purely vegetarian diet. Sale of dairy products has always been the mainstay of their economy. They earn their livelihood by selling milk and ghee (clarified butter) in the nearby towns and also supplement their income by selling dung manure. Their domestic livestock comprised mainly ofbuffaloes and cows, though they also possess camels which ane mainly used for tansport and as beasts ofburden. Their animals are kept together during night in circular thorn fencing known as 'Zok' and are let loose into the surrounding forests for grazing throughout the day. I)ependence of Maldhari on Protected Area: The following areas are identified in terms of dependence of maldhari on the protected area. Livestock Feeding: The livestock of maldhari are fully dependent on the protected area for green and dry fodder. The animals graze throughout the year. However, ttre availability of green grass is limited to only monsoon season and initial part of winter season. For rest of the year, the animals have to depend on dry grass. The availability of even dry grass becomes very limited duringthe summerwhich is stored forthe use during summer.In addition to feeding of grasses to their animals, they also provide some concentrate feeds like cottonseed and cottonseed cakes to their animals. -

Intersection of Ecology and Culture in Pastoral Landscape Banni Grassland .Kutch

Life of a Maldhari (Banni Pastoralist) “ When the land is discarded and the world called it as ‘waste’… When life is harsh and the extremities are the realities…. When the climate changes and hope remains, yet another day to survive persists, in search of grass heads held high, hearts tied to their cattle… a day dawns into another defining, the edges of landscape and traditions of the life….” Intersection of Ecology and Culture in Pastoral Landscape Banni Grassland .Kutch. India Jagadeesh Gorle Vandana Sreepada Divya Shah Camel Banni Horse Bunni Buffalo Kankrej Bull Goat Sheep Dromedary Equus caballus Bubalus bubalis Bos taurus indicus Capra aegagrus circus Ovis aries Nano Zinzvo Madhanu Khevai Sewan Dhaman Cenchrus Oin Cenchrus Dichanthium Cenchrus Eragrostis Eleusine Sporobolus setigerus cillaris Lasiurus helvolus annulatum Cressa cretica sindicus setigerus variablilis Indica Dhrab Chhabra Dhrabad Shiyal puch Desmotachya Cynodon Cynodon Chloris Chloris Suaeda Sporobolus Eragrostis bipinnata dactylon Eleusine Celianensis dactylon barbata barbata fruticosa diand&r Echinochloa Chiyo Madhanu Khariyu Kal Dactyloctenium Echinochloa Eleusine Cyperus Sachhurum Dactyloctenium Aeluropus aegyptium Sporobolus Eragrostis Colona Indica rotundus sindicum lagopoides Scirpus sps. spp Kutch Peninsula and Banni Grassland Half gabrion formation of Banni Grassland between Rann of Kutch Grass diversity and the Pastoral breeds developed by the local hereders in response and Bhuj Ridge with the land over generations Land in its Dynamic nature reflects in the -

1 Gggg Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge

gg1 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University 2019-2020 gg 12 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University Modern India has a history of a vibrant and active social sector. Many local development organisations, community organizations, social movements and non-governmental organisations populate the space of social action. Such organisations imagine a different future and plan and implement social interventions at different scales, many of which have lasting impact on the lives of people and society. However, their efforts and, more importantly, the learning from these initiatives remains largely unknown not only in the public sphere but also in the worlds of ‘development practice’ and ‘development education’. This shortfall impedes the process of learning and growth across interventions, organizations and time. While most social sector organizations acknowledge this deficiency in documentation and knowledge creation, they find themselves strapped for time and motivation to embark on such efforts. Writing with a sense of reflection and self-analysis which goes beyond mere documentation and creates a platform for learning requires time and space. As a result, their writing is usually limited to documentation captured in grant proposals or project updates or ‘good practices’ literature with inadequate focus on capturing the nuances, boundaries and limitations of action. Recognizing this need, the Azim Premji University launched ‘Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge’ with the objective of encouraging social sector organisations to invest in developing a grounded knowledge base for the sector. We are delighted to report that in the inaugural year of this challenge (2018 – 19) we received 95 cases, covering interventions from education, sustainability, livelihoods, preservation of culture and community health. -

State of Theworld's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009

Education special minority rights group international State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009 Events of 2008 State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009 Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International Minority Rights Group International (MRG) 54 Commercial Street, London, E1 6LT, United gratefully acknowledges the support of all organizations Kingdom. Tel +44 (0)20 7422 4200, Fax +44 (0)20 and individuals who gave financial and other assistance 7422 4201, Email [email protected] to this publication, including UNICEF and the Website www.minorityrights.org European Commission. Getting involved Minority Rights Group International MRG relies on the generous support of institutions Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a and individuals to further our work. All donations non-governmental organization (NGO) working to received contribute directly to our projects with secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples. minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, One valuable way to support us is to subscribe and to promote cooperation and understanding to our report series. Subscribers receive regular between communities. Our activities are focused MRG reports and our annual review. We also on international advocacy, training, publishing and have over 100 titles which can be purchased outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by from our publications catalogue. In addition, our worldwide partner network of organizations MRG publications are available to minority and which represent minority and indigenous peoples. indigenous peoples’ organizations through our MRG works with over 150 organizations in library scheme. nearly 50 countries. Our governing Council, which MRG’s unique publications provide well- meets twice a year, has members from 10 different researched, accurate and impartial information on State of countries. -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013

Focus on health minority rights group international State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013 Events of 2012 State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20131 Events of 2012 Front cover: A Dalit woman who works as a Community Public Health Promoter in Nepal. Jane Beesley/Oxfam GB. Inside front cover: Indigenous patient and doctor at Klinik Kalvary, a community health clinic in Papua, Indonesia. Klinik Kalvary. Inside back cover: Roma child at a community centre in Slovakia. Bjoern Steinz/Panos Acknowledgements Support our work Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate gratefully acknowledges the support of all organizations MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals who gave financial and other assistance and individuals to help us secure the rights of to this publication, including CAFOD, the European minorities and indigenous peoples around the Union and the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. world. All donations received contribute directly to our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. © Minority Rights Group International, September 2013. All rights reserved. Subscribe to our publications at www.minorityrights.org/publications Material from this publication may be reproduced Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe for teaching or for other non-commercial purposes. to our publications, which offer a compelling No part of it may be reproduced in any form for analysis of minority and indigenous issues and commercial purposes without the prior express original research. We also offer specialist training permission of the copyright holders. materials and guides on international human rights instruments and accessing international bodies. -

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text

The Idea of Gujarat History, Ethnography and Text Edited by EDWARD SIMPSON and MARNA KAPADIA ~ Orient BlackSwan THE IDEA OF GUJARAT. ORIENT BLACKSWAN PRIVATE LIMITED Registered Office 3-6-752 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A.P), India e-mail: [email protected] Other Offices Bangalore, Bhopal, Bhubaneshwar, Chennai, Ernakulam, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, ~ . Luoknow, Mumba~ New Delbi, Patna © Orient Blackswan Private Limited First Published 2010 ISBN 978 81 2504113 9 Typeset by Le Studio Graphique, Gurgaon 122 001 in Dante MT Std 11/13 Maps cartographed by Sangam Books (India) Private Limited, Hyderabad Printed at Aegean Offset, Greater Noida Published by Orient Blackswan Private Limited 1 /24 Asaf Ali Road New Delhi 110 002 e-mail: [email protected] . The external boundary and coastline of India as depicted in the'maps in this book are neither correct nor authentic. CONTENTS List of Maps and Figures vii Acknowledgements IX Notes on the Contributors Xl A Note on the Language and Text xiii Introduction 1 The Parable of the Jakhs EDWARD SIMPSON ~\, , Gujarat in Maps 20 MARNA KAPADIA AND EDWARD SIMPSON L Caste in the Judicial Courts of Gujarat, 180(}-60 32 AMruTA SHODaAN L Alexander Forbes and the Making of a Regional History 50 MARNA KAPADIA 3. Making Sense of the History of Kutch 66 EDWARD SIMPSON 4. The Lives of Bahuchara Mata 84 SAMIRA SHEIKH 5. Reflections on Caste in Gujarat 100 HARALD TAMBs-LYCHE 6. The Politics of Land in Post-colonial Gujarat 120 NIKITA SUD 7. From Gandhi to Modi: Ahmedabad, 1915-2007 136 HOWARD SPODEK vi Contents S. -

Missionary Biography, Mobin Khan

Editorial October 2018 SUBSCRIPTIONS Frontier Ventures-GPD, PO Box 91297 Long Beach, CA 90809, USA 1-888-881-5861 or 1-714-226-9782 for Canada and overseas PRAY FOR Dear Praying Friends, [email protected] The last two years I have attended the Finishing the Task EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Carey Every Unreached, Unengaged (FTT) conference here in Southern California. The purpose For comments on content call of this conference in simple terms is to get believers to 626-398-2241 or email [email protected] Muslim Group in India adopt (commit) to plant churches among the remaining ASSISTANT EDITOR people groups that lack a missionary presence. We call these Paula Fern “unengaged” unreached people groups. FTT produces lists WRITERS of these unreached, unengaged peoples (UUPGs), that are Eugena Chou changing as groups of believers adopt them. In fact, the list Patricia Depew Karen Hightower we used for this prayer guide changed right after I assigned Wesley Kawato stories to the writers! This month we will be praying for David Kugel Christopher Lane Muslim UUPGs in India. Ted Proffitt Cory Raynham Did you know you now can get FREE GPD materials? You Lydia Reynolds Jean Smith can still get the printed versions of our Global Prayer Digest, Allan Starling Chun Mei Wilson but we have a free app, that you can get by going to the John Ytreus Google Play Store and searching for “Global Prayer Digest.” DAILY BIBLE COMMENTARIES You can also get daily prayer materials in your inbox by Keith Carey going to our website and entering your email address in the CUSTOMER SERVICE box in the upper right corner.