Sounding Through Silence: Inter-Generational Voicings in Memoir, Memory, and Postmodernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Caio Fernando Abreu E O Cinema: O Processo De Adaptação De Morangos Mofados

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL FACULDADE DOS MEIOS DE COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL FABIANO GRENDENE DE SOUZA CAIO FERNANDO ABREU E O CINEMA: O PROCESSO DE ADAPTAÇÃO DE MORANGOS MOFADOS Porto Alegre 2010 FABIANO GRENDENE DE SOUZA CAIO FERNANDO ABREU E O CINEMA: O PROCESSO DE ADAPTAÇÃO DE MORANGOS MOFADOS Tese apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Comunicação, pelo Programa de Pós- graduação da Faculdade de Comunicação Social, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Gerbase Porto Alegre 2010 FABIANO GRENDENE DE SOUZA CAIO FERNANDO ABREU E O CINEMA: O PROCESSO DE ADAPTAÇÃO DE MORANGOS MOFADOS Tese apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Comunicação, pelo Programa de Pós- graduação da Faculdade de Comunicação Social, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Aprovada em_____de__________________de_____. BANCA EXAMINADORA Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Gerbase – PUCRS ______________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Michel Marie – Paris 3 – Sorbonne Nouvelle ______________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Renato Luiz Pucci Jr. – UTP _____________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Luís Augusto Fischer – UFRGS _____________________________________________ Prof. Dr Cristiane Freitas Gutfreind – PUCRS ______________________________________________ À Maria Clara, que terá 25 anos em 2022. À Gabi, minha pessoa-eu desde os meus 25. Aos meus pais, sempre pais-heróis, independente da minha idade. AGRADECIMENTOS Ao Gerbase, por acreditar no trabalho e em mim, mas também por Inverno, Deus-ex machina e Os replicantes. Ao Michel Marie, pela acolhida parisiense e por me mostrar o travelling de Tout va bien. À Cristiane Freitas, que só faltou comprar minha passagem para Paris. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

The Director's Idea

The Director’s Idea This Page is Intentionally Left Blank The Director’s Idea The Path to Great Directing Ken Dancyger New York University Tisch School of the Arts New York, New York AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Acquisitions Editor: Elinor Actipis Project Manager: Paul Gottehrer Associate Editor: Becky Golden-Harrell Marketing Manager: Christine Degon Veroulis Cover Design: Alisa Andreola Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2006, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) 1865 843830, fax: (ϩ44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier.com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Application submitted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication -

Sensate Focus (Mark Fell) Y (Sensate Focus 1.666666) [Sensate Focus

Sensate Focus (Mark Fell) Y (Sensate Focus 1.666666) [Sensate Focus / Editions M ego] Tuff Sherm Boiled [Merok] Ital - Ice Drift (Stalker Mix) [Workshop] Old Apparatus Chicago [Sullen Tone] Keith Fullerton Whitman - Automatic Drums with Melody [Shelter Press] Powell - Wharton Tiers On Drums [Liberation Technologies] High Wolf Singularity [Not Not Fun] The Archivist - Answers Could Not Be Attempted [The Archivist] Kwaidan - Gateless Gate [Bathetic Records] Kowton - Shuffle Good [Boomkat] Random Inc. - Jerusalem: Tales Outside The Framework Of Orthodoxy [RItornel] Markos Vamvakaris - Taxim Zeibekiko [Dust-To-Digital] Professor Genius - À Jean Giraud 4 [Thisisnotanexit] Suns Of Arqa (Muslimgauze Re-mixs) - Where's The Missing Chord [Emotional Rescue ] M. Geddes Genras - Oblique Intersection Simple [Leaving Records] Stellar Om Source - Elite Excel (Kassem Mosse Remix) [RVNG Intl.] Deoslate Yearning [Fauxpas Musik] Jozef Van Wissem - Patience in Suffering is a Living Sacrifice [Important Reords ] Morphosis - Music For Vampyr (ii) Shadows [Honest Jons] Frank Bretschneider machine.gun [Raster-Noton] Mark Pritchard Ghosts [Warp Records] Dave Saved - Cybernetic 3000 [Astro:Dynamics] Holden Renata [Border Community] the postman always rings twice the happiest days of your life escape from alcastraz laurent cantet guy debord everyone else olga's house of shame pal gabor billy in the lowlands chilly scenes of winter alambrista david neves lino brocka auto-mates the third voice marcel pagnol vecchiali an unforgettable summer arrebato attila -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Hliebing Dissertation Revised 05092012 3

Copyright by Hans-Martin Liebing 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Hans-Martin Liebing certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor Hans-Bernhard Moeller Charles Ramírez Berg Joseph D. Straubhaar Howard Suber Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood by Hans-Martin Liebing, M.A.; M.F.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication In loving memory of Christa Liebing-Cornely and Martha and Robert Cornely Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members Tom Schatz, Charles Ramírez Berg, Joe Straubhaar, Bernd Moeller and Howard Suber for their generous support and inspiring insights during the dissertation writing process. Tom encouraged me to pursue this project and has supported it every step of the way. I can not thank him enough for making this journey exciting and memorable. Howard’s classes on Film Structure and Strategic Thinking at The University of California, Los Angeles, have shaped my perception of the entertainment industry, and having him on my committee has been a great privilege. Charles’ extensive knowledge about narrative strategies and Joe’s unparalleled global media expertise were invaluable for the writing of this dissertation. Bernd served as my guiding light in the complex European cinema arena and helped me keep perspective. I consider myself very fortunate for having such an accomplished and supportive group of individuals on my doctoral committee. -

Indelible Shadows Film and the Holocaust

Indelible Shadows Film and the Holocaust Third Edition Annette Insdorf published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Annette Insdorf, 1983, 1989, 2002, 2003 Foreword to 1989 edition C Elie Wiesel This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First edition published 1983 by Random House Second edition published 1989 by Cambridge University Press Reprinted 1990 Third edition first published 2003 Printed in the United States of America Typefaces Minion 10/12 pt. and Univers67 System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Insdorf, Annette. Indelible shadows : film and the Holocaust / Annette Insdorf. – 3rd ed. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-521-81563-0 – ISBN 0-521-01630-4 (pb.) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in motion pictures. I. Title. PN1995.9.H53 I57 2002 791.43658 – dc21 2002023793 ISBN 0 521 81563 0 hardback ISBN 0 521 01630 4 paperback Contents Foreword by Elie Wiesel page xi Preface xiii Introduction xv I Finding an Appropriate Language 1. -

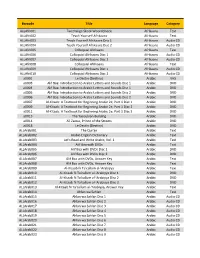

Barcode Title Language Category Allafri001 Tweetalige Skool

Barcode Title Language Category ALLAfri001 Tweetalige Skool-Woordeboek Afrikaans Text ALLAfri002 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri003 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri004 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri005 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri006 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri007 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri008 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri009 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri010 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD a0001 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic VHS a0003 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0004 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0005 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0006 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0007 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0009 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0011 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 3 Arabic DVD a0013 The Yacoubian Building Arabic DVD a0014 Ali Zaoua, Prince of the Streets Arabic DVD a0018 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic DVD ALLArab001 The Qur'an Arabic Text ALLArab002 Arabic-English Dictionary Arabic Text ALLArab003 Let's Read and Write Arabic, Vol. 1 Arabic Text ALLArab004 Alif Baa with DVDs Arabic Text ALLArab005 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 1 Arabic DVD ALLArab006 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 2 Arabic -

Titel Kino 2-2000

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 2/2000 At the Cannes International Film Festival: THE FAREWELL by Jan Schütte LOST KILLERS by Dito Tsintsadze NO PLACE TO GO by Oskar Roehler VASILISA by Elena Shatalova THE TIN DRUM – A LONE VICTOR On the History of the German Candidates for the Academy Award »SUCCESS IS IN THE DETAILS« A Portrait of Producer Kino Andrea Willson Scene from “THE FAREWELL” Scene from Studio Babelsberg Studios Art Department Production Postproduction Studio Babelsberg GmbH August-Bebel-Str. 26-53 D-14482 Potsdam Tel +49 331 72-0 Fax +49 331 72-12135 [email protected] www.studiobabelsberg.com TV SPIELFILM unterstützt die Aktion Shooting Stars der European Filmpromotion www.tvspielfilm.de KINO 2/2000 German Films at the 6 The Tin Drum – A Lone Victor 28 Cannes Festival On the history of the German candidates for the Academy Award 28 Abschied for Best Foreign Language Film THE FAREWELL Jan Schütte 11 Stations Of The Crossing 29 Lost Killers Portrait of Ulrike Ottinger Dito Tsintsadze 30 Die Unberührbare 12 Souls At The Lost-And-Found NO PLACE TO GO Portrait of Jan Schütte Oskar Roehler 31 Vasilisa 14 Success Is In The Details Elena Shatalova Portrait of Producer Andrea Willson 16 Bavarians At The Gate Bavaria Film International 17 An International Force Atlas International 18 KINO news 22 In Production 22 Die Blutgräfin 34 German Classics Ulrike Ottinger 22 Commercial Men 34 Es geschah am 20. Juli Lars Kraume – Aufstand gegen Adolf Hitler 23 Edelweisspiraten IT HAPPENED ON JULY 20TH Niko von Glasow-Brücher G. W. -

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters Ingrid Lewis B.A.(Hons), M.A.(Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of PhD June 2015 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Debbie Ging I hereby declare that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copywright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No: 12210142 Date: ii Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my most beloved parents, Iosefina and Dumitru, and to my sister Cristina I am extremely indebted to my supervisor, Dr. Debbie Ging, for her insightful suggestions and exemplary guidance. Her positive attitude and continuous encouragement throughout this thesis were invaluable. She’s definitely the best supervisor one could ever ask for. I would like to thank the staff from the School of Communications, Dublin City University and especially to the Head of Department, Dr. Pat Brereton. Also special thanks to Dr. Roddy Flynn who was very generous with his time and help in some of the key moments of my PhD. I would like to acknowledge the financial support granted by Laois County Council that made the completion of this PhD possible.