War Crimes in Shaping the Legacy of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACS35 10Pinto.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Justice Radhabinod Pal and the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal: A Political Retrospective of His Historic Dissent* Vivek Pinto History does not exist without people, and whatever is described happens through and to people.1) Geoffrey Elton, The Practice of History, 1967, 94. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal (officially the International Military Tribunal for the Far East) was set up by an executive order of General Douglas MacArthur (1880– 1964), the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, on January 19, 1946.2) The Charter set forth the constitution, jurisdiction and functions of the IMTFE. Earli- er, on September 2, 1945, MacArthur had accepted the Japanese surrender, aboard the USS Missouri. The IMTFEIMTFE began on May 3, 1946,1946, and ended sixty years agoago on November 12, 1948, when verdicts and the “majority opinion alone were read in open court and so became part of the transcript.”3) There were three dissenting, separate opinions. Eleven Justices constituted the IMTFE: one each from Australia, Canada, China, France, Great Britain, India, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, Soviet Union and United States. The dissent- ing opinions were from Justice Henri Bernard (France), Justice Radhabinod Pal (In- dia), and Justice Bert V. A. Röling (The Netherlands).4) Pal’s (1886–1967) lengthy dis- sent “argued for the acquittal on all counts of the accused Japanese wartime leaders.”5) His dissent “was as long as the twelve-hundred page majority” judgment.6) A leading historian, John Dower, comments: “SCAP did not permit Pal’s dissent to be translat- ed.”7) Richard Minear writes: “Tanaka Masaaki . -

Japanese Foreign Direct Investment in India: an Institutional Theory Approach Peter J

Business History Vol. 54, No. 5, August 2012, 657–688 Japanese foreign direct investment in India: An institutional theory approach Peter J. Buckleya*, Adam R. Crossa and Sierk A. Hornb aCentre for International Business (CIBUL), Leeds University Business School, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; bDepartment of East Asian Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK This article charts the history of Japanese corporate engagement with India. While there has been a profound historic relationship between the two nations, economic interaction is commonly portrayed in the context of geographical and psychic distance. As institutions set the rules of corporate engagement, we analyse the evolving regulatory and policy regime for foreign direct investment (FDI) in post-independence India and the corporate strategies of Japanese multinational enterprises (MNEs) in response to this institutional change. Using a firm-level dataset we show that the trajectory of Japanese investment in India broadly follows that of other nationalities of foreign firms. Differentiated responses to institutional changes are detected by industry. Our analysis reveals important instances of Japanese firm flexibility and pragmatism vis-a` -vis the rapidly growing Indian market. Keywords: foreign direct investment; emerging economies; Japan; India; international corporate strategies Introduction Over the past four decades, considerable scholarly attention has been paid to identifying and explaining the determinants and consequences of Japanese foreign direct investment (FDI) and the international expansion strategies of Japanese multinational enterprises (MNEs). However, the majority of this work is set within the particular context of industrialised countries as destinations for Japanese FDI (e.g., Ford & Strange, 1999; Head, Ries, & Swenson, 1995; Thiran &Yamawaki, 1995). -

Japan Relations the Friendship Between India and Japan Has a Long History Rooted in Spiritual Affinity and Strong Cultur

India - Japan Relations The friendship between India and Japan has a long history rooted in spiritual affinity and strong cultural and civilizational ties. The modern nation states have carried on the positive legacy of the old association which has been strengthened by shared values of belief in democracy, individual freedom and the rule of law. Over the years, the two countries have built upon these values and created a partnership based on both principle and pragmatism. Today, India is the largest democracy in Asia and Japan the most prosperous. India’s earliest documented direct contact with Japan was with the TodaijiTemple in Nara, where the consecration or eye-opening of the towering statue of lord Buddha was performed by an Indian monk, Bodhisena, in 752 AD. In contemporary times, among other Indians associated with Japan were the Hindu leader Swami Vivekananda, Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, entrepreneur JRD Tata, freedom fighter Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and Judge RadhaBinod Pal. The Japan-India Association was set up in 1903, and is today the oldest international friendship body in Japan. Throughout the various phases of history since civilizational contacts between India and Japan began some 1400 years ago, the two countries have never been adversaries. Bilateral ties have been singularly free of any kind of dispute – ideological, cultural or territorial. The relationship is unique and one of mutual respect manifested in generous gestures and sentiments, and of standing by each other at times of need. Post the Second World War, India did not attend the San Francisco Conference, but decided to conclude a separate peace treaty with Japan in 1952 after its sovereignty was fully restored, marking a defining moment in the bilateral relations and setting the tone for the future. -

India-Japan Relations India-Japan Relations

RSIS Monograph No. 23 INDIA-JAPAN RELATIONS RELATIONS INDIA-JAPAN INDIA-JAPAN RELATIONS DRIVERS, TRENDS AND PROSPECTS Arpita Mathur RSIS Monograph No. 23 Arpita Mathur RSIS MONOGRAPH NO. 23 INDIA-JAPAN RELATIONS DRIVERS, TRENDS AND PROSPECTS Arpita Mathur S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Copyright © 2012 Arpita Mathur Published by S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University South Spine, S4, Level B4, Nanyang Avenue Singapore 639798 Telephone: 6790 6982 Fax: 6793 2991 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.rsis.edu.sg First published in 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Body text set in 11/14 point Warnock Pro Produced by BOOKSMITH ([email protected]) ISBN 978-981-07-2803-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Setting the Stage: India and Japan in History 1 Chapter 2 The Post-Cold War Turn 16 Chapter 3 The Drivers 33 Chapter 4 Strategic and Political Relations 50 Chapter 5 Economic Linkages 70 Chapter 6 Non-Traditional Security: Building Bridges 92 Chapter 7 Conclusion 118 About the Author 130 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This monograph is the outcome of my research in the South Asia Programme of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Stud- ies (RSIS). I am indebted to Dr. Rajesh Basrur, Senior Fellow and Head of the Programme, for providing me the opportunity to work on a subject I have always been interested in exploring. -

KFG Working Paper No. 10 Druckversion

KFG Working Paper Series • No. 10 • June 2017 Aniruddha Rajput Protection of Foreign Investment in India and International Rule of Law: Rise or Decline? – Rise or Decline?“ Potsdam Research Group „The International Rule of Law Berlin 2 | KFG Working Paper No. 10 | June 2017 KFG Working Paper Series Edited by Heike Krieger, Georg Nolte and Andreas Zimmermann All KFG Working Papers are available on the KFG website at www.kfg-intlaw.de. Copyright remains with the authors. Rajput, Aniruddha, Protection of Foreign Investment in India and International Rule of Law: Rise or Decline?, KFG Working Paper Series, No. 10, Berlin Potsdam Research Group “The International Rule of Law – Rise or Decline?”, Berlin, June 2017. ISSN 2509-3770 (Internet) ISSN 2509-3762 (Print) This publication has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) Product of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Commercial use is not permitted Berlin Potsdam Research Group International Law – Rise or Decline? Unter den Linden 9 10099 Berlin, Germany [email protected] +49 (0)30 2093-3322 www.kfg-intlaw.de The International Rule of Law – Rise or Decline? | 3 Protection of Foreign Investment in India and International Rule of Law: Rise or Decline?* Aniruddha Rajput 1 Abstract: This paper narrates the changes in the Indian policy towards foreign investment and analyses them in the backdrop of overall changes in the field of international law and particularly within the framework of the international rule of law. The policy changes that have taken place in India can be categorised into three periods. The first period commences after independence from colonial rule. -

Neuf Au Rcpl Et Six Au

MAZAVAROO | N°28 | SAMEDI 8 FÉVRIER 2020 mazavaroo.mu RS 5.00 PAGES 4-5 Raj Pentiah : "Je regrette d'avoir cru dans le volume de mensonges de navin ramgoolam" SMP.MU 14 N°28 - SAMEDI 08 FEVRIER 2020 PAGES 6-7 Pages 18-19 Discours-Programme Neuf au RCpl et six au RCc MarieLes "YoungClaire Phokeerdoss Shots" Les Royalistes accaparent 1/3 de la RENCONTREcuvée de 2019 du MSM volent Marie Claire Phokeerdoss:la vedette « La SMP vient en aide aux démunis de Beau-Vallon » arie Claire Phokeerdoss est âgée de 73 ans. Elle a sous sa responsabilité deux petits-enfants et dépend uniquement de sa pension de vieillesse pour les nourrir. Marie Claire raconte qu’elle pu mo okip 2 zenfants, lavi trop Ms’occupe des enfants de sa fille chere, » affirme-t-elle. depuis qu’ils sont nés. « Zot ti Afin d’aider Marie Claire à encore tibaba ler zot inn vinn ress joindre les deux bouts, la SMP a avek moi. Ena fois zot mama vinn offert des fournitures scolaires à guet zot, » dit-elle avec tristesse. ses petits-enfants. « Ban zenfan la La septuagénaire ne baisse jamais inn gagne ban materiaux scolaires. PAGE 3 les bras. Avec le soutien des autres Zot inn gagne sak, soulier lekol, membres de sa famille, Marie cahier ek ban lezot zafer lekol, Claire essaie tant bien que mal » dit-elle avec satisfaction. « Sa editorial de subvenir aux besoins de ses fer moi enn gran plaisir ki ban deux petits-enfants, âgés de 5 association cuma SMP pe vinn et 11 ans. -

NASSDOC Research Information Series: 3

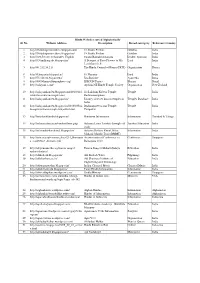

NASSDOC Research Information Series: 3 Vol. 2 No.2 April - June 2017 National Social Science Documentation Centre Indian Council of Social Science Research 35, Ferozeshah Road New Delhi-110001 www.icssr.org Mail: [email protected] Current Contents A Quarterly Issue Edited & Compiled by S N Chari NASSDOC Research Information Series: 3 © ICSSR-NASSDOC, New Delhi Vol.2 No.2 April-June 2017, 115p. FOREWORD Current Contents is a Current Awareness Service under ”NASSDOC Research Information Series". It provides ready access to bibliographic details of articles from the recently published leading scholarly journals in Social Sciences and available in NASSDOC. In this publication, “Table of Contents” of selected journals are arranged under title of the journal and at its end Author Index and Keyword Indexes have been provided in alphabetical order. While adequate care has been taken in reproducing the information from various scholarly journals received in NASSDOC, but NASSDOC does not take legal responsibility for its correctness. It is only for information and is based on information collected journals received in NASSDOC. Nutan Johry NASSDOC (In-charge) CONTENTS S. Name of the Journal Vol./ Month & Page NO Issue Year No 1 Administrative Science Quarterly 62/2 June 2017 1 2 Advances in Developing Human Resources 19/2 May 2017 2 3 American Economic Review 107/4 April 2017 3 4 American Economic Review 107/5 May 2017 4 5 American Economic Review 107/6 June 2017 16 6 American Journal of Economic and Sociology 76/3 June 2017 17 7 The American -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

Title Japan and India:Looking Beyond the Economy Author(S)

Title Japan and India:Looking Beyond the Economy Author(s) Nakamizo, Kazuya Citation nippon.com (2019) Issue Date 2019-10-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/259823 Some parts of this PDF were redacted for permission condition. 許諾条件により非表示の部分があります.; This PDF is Right deposited under the publisher's permission. 発行元の許可を得 て登録しています. Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Home In-depth Japan and India: Looking Beyond the Economy Japan and India: Looking Beyond the Economy Politics Oct 25, 2019 Nakamizo Kazuya [Profile] Narendra Modi has embarked on his second term as India’s prime minister, following a convincing victory in May’s elections. In this article, a leading specialist on South Asian affairs argues that Japan is wrong to focus exclusively on economic cooperation in its relations with India, and should no longer turn a blind eye to the dangerous side of Modi’s Hindu supremacist project. Against most expectations, Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party won a convincing victory in the general elections in India in May this year. The response from the Japanese government and business leaders has been overwhelmingly positive, and Prime Minister Abe Shinzō lost no time in sending his congratulations becoming the first foreign leader to do so. A report in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper on May 24 quoted a senior figure involved in Japan’s foreign policy as saying that the next five years promised to be an ideal period for building a closer relationship between Japan and India in fields such as national security and economic cooperation. Personally, I predict that the BJP government is settling in for a long period (Nakamizo 2019). -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

The Elephant and the Samurai: Why Japan Can Trust India?

BOOK REVIEW The Elephant and The Samurai: Why Japan Can Trust India? by Dr. Rupakjyoti Borah (Kaveri Books, Delhi, 2017. 160 pp. Rs 450) Author Aftab Seth By Aftab Seth Overview of India-Japan Relations are regarded as true friends of Japan. India under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru refused to sign the This slim volume provides a comprehensive overview of the Treaty of San Francisco as it did not uphold the dignity of Japan. developments in India’s relations with Japan from early times almost Instead India signed a separate peace treaty with Japan at the end of 1,500 years ago to the present time. The author traces our the American occupation and waived all rights to receive war relationship to Bodhisena, the Indian monk who arrived in Japan in reparations from Japan. This act and the gift of a baby elephant to 752 AD for the eye-opening ceremony of the Diabutsu in Todaiji in Ueno Zoo were symbols of India’s feelings of friendship for Japan Nara. In modern times a Japanese consulate was established in and influenced an entire generation of Japanese. But India’s policy of Bombay in 1893 and the NYK line began a service from Kobe to non-alignment and Japan’s security treaty with the United States kept Bombay. There was great interaction between scholars like Okakura the two countries apart during the Cold War years. India’s nuclear Tenshin and Rabindranath Tagore, and later between Rash Behari test in 1974 was another reason for Japan’s aloofness towards India. Bose and Netaji Subhas Bose and the Japanese politicians of those Yet bilateral ties took a dramatic turn for the better at the turn of the times.