Legislation Review Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 15 October 2019 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 15 October 2019 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 14:30. The PRESIDENT read the prayers and acknowledged the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thanked them for their custodianship of this land. Governor ADMINISTRATION OF THE GOVERNMENT The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of a message regarding the administration of the Government. Bills ABORTION LAW REFORM BILL 2019 Assent The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of message from the Governor notifying Her Excellency's assent to the bill. REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE REFORM BILL 2019 Protest The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of the following communication from the Official Secretary to the Governor of New South Wales: GOVERNMENT HOUSE SYDNEY Wednesday, 2 October, 2019 The Clerk of the Parliaments Dear Mr Blunt, I write at Her Excellency's command, to acknowledge receipt of the Protest made on 26 September 2019, under Standing Order 161 of the Legislative Council, against the Bill introduced as the "Reproductive Health Care Reform Bill 2019" that was amended so as to change the title to the "Abortion Law Reform Bill 2019'" by the following honourable members of the Legislative Council, namely: The Hon. Rodney Roberts, MLC The Hon. Mark Banasiak, MLC The Hon. Louis Amato, MLC The Hon. Courtney Houssos, MLC The Hon. Gregory Donnelly, MLC The Hon. Reverend Frederick Nile, MLC The Hon. Shaoquett Moselmane, MLC The Hon. Robert Borsak, MLC The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox, MLC The Hon. Mark Latham, MLC I advise that Her Excellency the Governor notes the protest by the honourable members. -

(Legislative Council, 24 November 2011, Proof) POLICE

Full Day Hansard Transcript (Legislative Council, 24 November 2011, Proof) Proof Extract from NSW Legislative Council Hansard and Papers Thursday, 24 November 2011 (Proof). POLICE AMENDMENT (DEATH AND DISABILITY) BILL 2011 Second Reading Debate resumed from 23 November 2011. The Hon. ROBERT BROWN [8.04 p.m.]: I am happy to make a contribution in relation to the Police Amendment (Death and Disability) Bill 2011. A considerable amount of work has been done during this week by the Minister for Police and Emergency Services and his staff and the Police Association. I have a sense that we are there. Let me define there: My left hand is stretched out to the left-hand side of my body, and that is where the Government started; my right hand is stretched out to the right-hand side of my body, and that is where the Police Association started. They are not in the middle but they are somewhere closer to where the Police Association probably wants to be for its members than I thought was possible a week ago. We have attempted to test the Government's position on the issues that the Police Association has brought to the Christian Democratic Party and the Shooters and Fishers Party. We have done that this week in a number of meetings with both parties individually and with both parties in the same room. Neither the Christian Democratic Party nor the Shooters and Fishers Party have members who are professional advocates—although both Mr Borsak and I have done quite a bit of that sort of thing in our time in business—and it has been an extremely difficult process. -

BUSINESS PROGRAM Fifty-Seventh Parliament, First Session Legislative Assembly

BUSINESS PROGRAM Fifty-Seventh Parliament, First Session Legislative Assembly Thursday 18 March 2021 At 9.30 am Giving of Notices of Motions (General Notices) (for up to 15 minutes) GOVERNMENT BUSINESS (for up to 30 minutes) Orders of the Day No. 3 Budget Estimates and related papers 2020-2021; resumption of the interrupted debate (Mr Dominic Perrottet – Mr Alister Henskens speaking, 2 minutes remaining (after obtaining an extension). * denotes Member who adjourned the debate GENERAL BUSINESS Notices of Motions (for Bills) (for up to 20 minutes) No. 1 Independent Commission Against Corruption Amendment (Publication of Ministerial Register of Interests) Bill (Ms Jodi McKay). No. 2 Canterbury Park Racecourse (Sale and Redevelopment Moratorium) Bill (Ms Sophie Cotsis). Orders of the Day (for Bills) (for up to 90 minutes) No. 1 Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Amendment (Coercive Control – Preethi's Law) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Ms Anna Watson – Mr Stephen Bali speaking, 1 minute remaining). No. 2 Local Government Amendment (Pecuniary Interests Disclosures) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Mr Greg Warren – Ms Melanie Gibbons*). †No. 3 Liquor Amendment (Right to Play Music) Bill – awaiting second reading speech (Ms Sophie Cotsis.) †No. 4 State Insurance and Care Government Amendment (Employees) Bill – awaiting second reading speech (Ms Sophie Cotsis). No. 5 Independent Commission Against Corruption Amendment (Property Developer Commissions to MPs) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Ms Jodi McKay – Mr Michael Johnsen*). †No. 6 ICAC and Other Independent Commission Legislation Amendment (Independent Funding) Bill – awaiting second reading speech (Mrs Helen Dalton). No. 7 Government Information (Public Access) Amendment (Recklessly Destroying Government Records) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Ms Jodi McKay – Ms Melanie Gibbons*). -

Transcript of Today's Hearing Will Be Placed on the Committee's Website When It Becomes Available

REPORT ON PROCEEDINGS BEFORE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE GOVERNMENT'S MANAGEMENT OF THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM AND OTHER MUSEUMS AND CULTURAL PROJECTS IN NEW SOUTH WALES INQUIRY INTO THE GOVERNMENT'S MANAGEMENT OF THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM AND OTHER MUSEUMS AND CULTURAL PROJECTS IN NEW SOUTH WALES UNCORRECTED At Jubilee Room, Parliament House, Sydney on Monday, 15 February 2021 The Committee met at 9:15 am PRESENT The Hon. Robert Borsak (Chair) The Hon. Ben Franklin The Hon. Rose Jackson The Hon. Trevor Khan The Hon. Taylor Martin The Hon. Walt Secord Mr David Shoebridge (Deputy Chair) Monday, 15 February 2021 Legislative Council - UNCORRECTED Page 1 The CHAIR: Welcome to the fifth hearing of the Select Committee on the Government's management of the Powerhouse Museum and other museums and cultural projects in New South Wales. The inquiry is examining issues surrounding the Government's proposal for the Powerhouse Museum and support for the State's museums and cultural sector more broadly. Before I commence, I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal people, who are the traditional custodians of this land. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past and present of the Eora nation and extend that respect to other Aboriginals present. This morning we will hear from Government witnesses from the arts and infrastructure portfolios, including the Hon. Don Harwin, MLC, followed by the chairman of Western Sydney Powerhouse Museum Community Alliance. After lunch we will hear evidence from the CFMMEU, a flood expert and a Parramatta councillor. Before we commence I would like to make some brief comments about the procedures for today's hearing. -

2019 Nsw State Budget Estimates – Relevant Committee Members

2019 NSW STATE BUDGET ESTIMATES – RELEVANT COMMITTEE MEMBERS There are seven “portfolio” committees who run the budget estimate questioning process. These committees correspond to various specific Ministries and portfolio areas, so there may be a range of Ministers, Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries and senior public servants from several Departments and Authorities who will appear before each committee. The different parties divide up responsibility for portfolio areas in different ways, so some minor party MPs sit on several committees, and the major parties may have MPs with titles that don’t correspond exactly. We have omitted the names of the Liberal and National members of these committees, as the Alliance is seeking to work with the Opposition and cross bench (non-government) MPs for Budget Estimates. Government MPs are less likely to ask questions that have embarrassing answers. Victor Dominello [Lib, Ryde], Minister for Customer Services (!) is the minister responsible for Liquor and Gaming. Kevin Anderson [Nat, Tamworth], Minister for Better Regulation, which is located in the super- ministry group of Customer Services, is responsible for Racing. Sophie Cotsis [ALP, Canterbury] is the Shadow for Better Public Services, including Gambling, Julia Finn [ALP, Granville] is the Shadow for Consumer Protection including Racing (!). Portfolio Committee no. 6 is the relevant committee. Additional information is listed beside each MP. Bear in mind, depending on the sitting timetable (committees will be working in parallel), some MPs will substitute in for each other – an MP who is not on the standing committee but who may have a great deal of knowledge might take over questioning for a session. -

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I Have Fond Memories of the Friendly, Knowledgeable Giraffe

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I have fond memories of the friendly, knowledgeable giraffe. Harold takes you on a magical journey exploring and learning about healthy eating, our body - how it works and ways we can be active in order to stay happy and healthy. It gives me such joy to see how excited my daughter is to visit Harold and know that it will be an experience that will stay with her too. Melanie, parent, Turramurra Public School What’s inside Who we are 03 Our year Life Education is the nation’s largest not-for-profit provider of childhood preventative drug and health education. For 06 Our programs almost 40 years, we have taken our mobile learning centres and famous mascot – ‘Healthy Harold’, the giraffe – to 13 Our community schools, teaching students about healthy choices in the areas of drugs and alcohol, cybersafety, nutrition, lifestyle 25 Our people and respectful relationships. 32 Our financials OUR MISSION Empowering our children and young people to make safer and healthier choices through education. OUR VISION Generations of healthy young Australians living to their full potential. LIFE EDUCATION NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report Our year: Thank you for being part of Life Education NSW Together we worked to empower more children in NSW As a charity, we’re grateful for the generous support of the NSW Ministry of Health, and the additional funds provided by our corporate and community partners and donors. We thank you for helping us to empower more children in NSW this year to make good life choices. -

EMAIL ADDRESS Postal Address for All Upper House Members

TITLE NAME EMAIL ADDRESS Phone Postal Address for all Upper House Members: Parliament House, 6 Macquarie St, Sydney NSW, 2000 Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party The Hon. Robert Borsak [email protected] (02) 9230 2850 The Hon. Robert Brown [email protected] (02) 9230 3059 Liberal Party The Hon. John Ajaka [email protected] (02) 9230 2300 The Hon. Lou Amato [email protected] (02) 9230 2764 The Hon. David Clarke [email protected] (02) 9230 2260 The Hon. Catherine Cusack [email protected] (02) 9230 2915 The Hon. Scott Farlow [email protected] (02) 9230 3786 The Hon. Don Harwin [email protected] (02) 9230 2080 Mr Scot MacDonald [email protected] (02) 9230 2393 The Hon. Natasha Maclaren-Jones [email protected] (02) 9230 3727 The Hon. Shayne Mallard [email protected] (02) 9230 2434 The Hon. Taylor Martin [email protected] 02 9230 2985 The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox [email protected] (02) 9230 3557 The Hon. Greg Pearce [email protected] (02) 9230 2328 The Hon. Dr Peter Phelps [email protected] (02) 9230 3462 National Party: The Hon. Niall Blair [email protected] (02) 9230 2467 The Hon. Richard Colless [email protected] (02) 9230 2397 The Hon. Wes Fang [email protected] (02) 9230 2888 The Hon. -

Portfolio Committee No. 4 – Legal Affairs

REPORT ON PROCEEDINGS BEFORE PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE NO. 4 – LEGAL AFFAIRS EMERGENCY SERVICES AGENCIES UNCORRECTED PROOF At Macquarie Room, Parliament House, Sydney on Monday, 18 September 2017 The Committee met at 12:00 PRESENT The Hon. R. Borsak (Chair) The Hon. D. Clarke The Hon. C. Cusack The Hon. G. Donnelly The Hon. T. Khan The Hon. P. Primrose Mr D. Shoebridge The Hon. L. Voltz Monday, 18 September 2017 Legislative Council Page 1 The CHAIR: Welcome to the first hearing of Portfolio Committee No. 4 inquiring into emergency services agencies. Before I commence I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal people who are the traditional custodians of this land. I would also like to pay respect to elders past and present of the Eora nation and extend that respect to other Aboriginals present. The Committee is here today because our inquiry is considering the policy response to bullying, harassment and discrimination in emergency services agencies, including the NSW Rural Fire Service, Fire and Rescue NSW, the NSW Police Force, the Ambulance Service of NSW and the NSW State Emergency Service. This includes examining the prevalence of the issue, the effectiveness of what is in place to manage and resolve such complaints, along with what support is available for victims, workers and volunteers of emergency services agencies. Today is the first of several hearings we plan to hold for this inquiry. We will hear today from representatives of the Volunteer Fire Fighters Association, representatives from the NSW Rural Fire Service Association and senior officers from the NSW Rural Fire Service. I would like also to make some brief comments about the procedures for today's hearing. -

BUSINESS PROGRAM Fifty-Seventh Parliament, First Session Legislative Assembly

BUSINESS PROGRAM Fifty-Seventh Parliament, First Session Legislative Assembly Thursday 18 February 2021 At 9.30 am Giving of Notices of Motions (General Notices) (for up to 15 minutes) GOVERNMENT BUSINESS (for up to 30 minutes) Notices of Motion 1. COVID-19 Legislation Amendment (Stronger Communities and Health) Bill 2021 (Mr Mark Speakman) Orders of the Day No. 3 Budget Estimates and related papers 2020-2021; resumption of the interrupted debate (Mr Dominic Perrottet – Mr Zangari speaking, 11 minutes remaining). * denotes Member who adjourned the debate GENERAL BUSINESS Notices of Motions (for Bills) (for up to 20 minutes) No. 2 Independent Commission Against Corruption Amendment (Ministerial Code of Conduct – Property Developers) Bill (Ms Jodi McKay). No. 3 NSW Jobs First Bill (Ms Yasmin Catley) Orders of the Day (for Bills) (for up to 90 minutes) No. 1 Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Amendment (Coercive Control – Preethi's Law) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Ms Anna Watson – Ms Tanya Davies speaking, 7 minutes remaining). No. 2 Local Government Amendment (Pecuniary Interests Disclosures) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Mr Greg Warren – Ms Melanie Gibbons*). †No. 3 Liquor Amendment (Right to Play Music) Bill – awaiting second reading speech (Ms Sophie Cotsis.) †No. 4 State Insurance and Care Government Amendment (Employees) Bill – awaiting second reading speech (Ms Sophie Cotsis). No. 5 Independent Commission Against Corruption Amendment (Property Developer Commissions to MPs) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Ms Jodi McKay – Mr Michael Johnsen*). †No. 6 ICAC and Other Independent Commission Legislation Amendment (Independent Funding) Bill – awaiting second reading speech (Mrs Helen Dalton). -

Transcript of Today's Hearing Will Be Placed on the Committee's Website When It Becomes Available

REPORT ON PROCEEDINGS BEFORE PUBLIC ACCOUNTABILITY COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO INTEGRITY, EFFICACY AND VALUE FOR MONEY OF NSW GOVERNMENT GRANT PROGRAMS CORRECTED At Jubilee Room, Parliament House, Sydney on Friday 16 October 2020 The Committee met at 9:00 am PRESENT The Hon. John Graham (Acting Chair) The Hon. Trevor Khan The Hon. Courtney Houssos The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox The Hon. Natalie Ward PRESENT VIA VIDEOCONFERENCE The Hon. Lou Amato Mr David Shoebridge Friday, 16 October 2020 Legislative Council Page 1 CORRECTED The ACTING CHAIR: Welcome to the second hearing of the Public Accountability Committee's inquiry into integrity, efficacy and value for money of New South Wales Government grant programs. Before I commence I acknowledge the Gadigal people who are the traditional custodians of this land. I also pay respect to Elders of the Eora nation past, present and emerging, and I extend that respect to other First Nation people present. Today's hearing will focus on local council and Government grant programs. We will hear from the Independent Commission Against Corruption, the Auditor-General and the Department of Regional NSW. Before we commence I will make some brief comments about the procedures. Today's hearing is being broadcast live via the Parliament's website. A transcript of today's hearing will be placed on the Committee's website when it becomes available. I note that I am serving today as Acting Chair, as we are joined by the Chair of the Committee, Mr David Shoebridge, via teleconference. Other Committee members are either present or joining us shortly. Parliament House is now open to the public. -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 4 August 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 4 August 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 12:00. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. [Notices of motions given.] Bills GAS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (MEDICAL GAS SYSTEMS) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Kevin Anderson, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr KEVIN ANDERSON (Tamworth—Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation) (12:16:12): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I am proud to introduce the Gas Legislation Amendment (Medical Gas Systems) Bill 2020. The bill delivers on the New South Wales Government's promise to introduce a robust and effective licensing regulatory system for persons who carry out medical gas work. As I said on 18 June on behalf of the Government in opposing the Hon. Mark Buttigieg's private member's bill, nobody wants to see a tragedy repeated like the one we saw at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. As I undertook then, the Government has taken the steps necessary to provide a strong, robust licensing framework for those persons installing and working on medical gases in New South Wales. To the families of John Ghanem and Amelia Khan, on behalf of the Government I repeat my commitment that we are taking action to ensure no other families will have to endure as they have. The bill forms a key part of the Government's response to licensed work for medical gases that are supplied in medical facilities in New South Wales. -

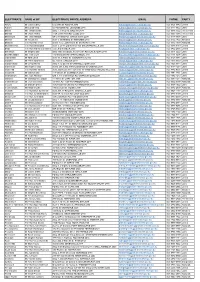

NSW Govt Lower House Contact List with Hyperlinks Sep 2019

ELECTORATE NAME of MP ELECTORATE OFFICE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PARTY Albury Mr Justin Clancy 612 Dean St ALBURY 2640 [email protected] (02) 6021 3042 Liberal Auburn Ms Lynda Voltz 92 Parramatta Rd LIDCOMBE 2141 [email protected] (02) 9737 8822 Labor Ballina Ms Tamara Smith Shop 1, 7 Moon St BALLINA 2478 [email protected] (02) 6686 7522 The Greens Balmain Mr Jamie Parker 112A Glebe Point Rd GLEBE 2037 [email protected] (02) 9660 7586 The Greens Bankstown Ms Tania Mihailuk 9A Greenfield Pde BANKSTOWN 2200 [email protected] (02) 9708 3838 Labor Barwon Mr Roy Butler Suite 1, 60 Maitland St NARRABRI 2390 [email protected] (02) 6792 1422 Shooters Bathurst The Hon Paul Toole Suites 1 & 2, 229 Howick St BATHURST 2795 [email protected] (02) 6332 1300 Nationals Baulkham Hills The Hon David Elliott Suite 1, 25-33 Old Northern Rd BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 [email protected] (02) 9686 3110 Liberal Bega The Hon Andrew Constance 122 Carp St BEGA 2550 [email protected] (02) 6492 2056 Liberal Blacktown Mr Stephen Bali Shop 3063 Westpoint, Flushcombe Rd BLACKTOWN 2148 [email protected] (02) 9671 5222 Labor Blue Mountains Ms Trish Doyle 132 Macquarie Rd SPRINGWOOD 2777 [email protected] (02) 4751 3298 Labor Cabramatta Mr Nick Lalich Suite 10, 5 Arthur St CABRAMATTA 2166 [email protected] (02) 9724 3381 Labor Camden Mr Peter Sidgreaves 66 John St CAMDEN 2570 [email protected] (02) 4655 3333 Liberal