The Background to the Far East Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 21 DECEMBER, 1944 5859 No

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 21 DECEMBER, 1944 5859 No. 6475789 Sergeant Charles Frederick Claxson, No. 5675753 Corporal (acting Sergeant) Reginald The Queen's' Royal Regiment (West Surrey) Hayman, The Somerset Light Infantry (Wake- (Upminster). • field). No. 6094273 Corporal (acting Sergeant) Georgjc- No. 14401018 Corporal James Henry Lang McClernon, Bernard Boswell, The Queen's Royal Regiment The Somerset Light Infantry (Edmonton) (since (West Surrey). killed in action). No. 5670092 Lance-Sergeant .Ernest Arthur Giles, The No. 4342188 Corporal (acting Warrant Officer Class II Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) (High- (Company Sergeant-Major) ) George Henry Webb, bridge). M.M., The East Yorkshire Regiment (The Duke of No. 60,89761 Corporal Frank Shepherd, The Queen's 1 York's Own) (Manchester). Royal Regiment (West Surrey) '(Woking). No. 4350748 Lance-Sergeant John Samuel Scruton, No. 6095128 Corporal Ronald Keith Ward, The The East Yorkshire Regiment (The Duke of York's Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) (Catford). Own) (Hull). No. 6098820 Lance-Corporal Edward Gray, The No. 4535654 Corporal Joseph Grace, The East York- Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) (Epsom). shire Regiment (The Duke of York's Own) No. 6150533 Lance-Corporal Edward Took, The '(Batley, Yorks.). Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) (London, No.1 4341934 Lance-Corporal Robert Sidney Jones, S.E.7). The East Yorkshire Regiment (The Duke of York's No. 3129772 Lance-Corporal Alex. Walker, The . Own). (Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) (Txoon). No. 4459550 Private Elijah Carr, The East Yorkshire No. 3782716 Private Joshua Rawcliffe Pilkington, Regiment (The Duke of Yorks Own), (Meadowfield, The Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) Co. -

Page 1 /4 26Th November 2019 Dear Sir/Madam, STAKEHOLDER

26th November 2019 Dear Sir/Madam, STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION INVITATION TO COMMENT ON RSPO (P&C) INITIAL CERTIFICATION AUDIT We are pleased to invite you to attend and provide comments in the stakeholder consultation meeting. Felda Global Ventures (FGV) Berhad, has applied to Global Gateway Certifications Sdn Bhd to carryout certification activities in accordance with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO P&C) standards. The standards that shall be applied in the assessment are as below; RSPO Principle & Criteria Certification (RSPO P&C 2018) – MALAYSIA NATIONAL INTERPRETATION (MYNI) Nov 2019 dan RSPO Supply Chain Certification Standard (21st November 2014) revised on 14th June 2017. As planned, the auditing will be conducted on 26th December 2019 and ended on 28th December 2019. Audit team cordially to invite any stakeholders or interested parties to attend our Stakeholder Meeting planned to be conducted on: Date : 26th December 2019 Time : 11.00 am to 13.00 pm Location : FGVPISB Kilang Sawit Tenggaroh Timur, Kota Tinggi, Johor. Note *: If you are unable to attend the meeting you are most welcome to meet our audit team and convey your comments during any of the audit days. Applicant FGVPISB Kilang Sawit Tenggaroh Timur RSPO Membership 1–0225–16–000–00 (Ordinary Member) Ameer Izyanif Bin Hamzah Level 20, West Wisma FGV, Contact details Jalan Raja Laut 50350, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia [email protected] / www.fgvholdings.com FGV operates in more than 10 countries across Asia, the Middle East, North America, and Europe, and is focused on three main sectors: Plantations, Sugar and Logistics & Support Businesses. Incorporated in 2007 as a private limited company, FGV initially operated as the commercial arm of Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA) prior to its listing Brief business in the main market of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad on 28 June 2012 as Felda information of Global Ventures Holdings Berhad. -

Investigation of Road Crash Rate at FT050, Jalan Batu Pahat – Kluang: Pre and Post Road Median Divider

International Journal of Road Safety 1(1) 2020: 16-19 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ International Journal of Road Safety Journal homepage: www.miros.gov.my/journal _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Investigation of Road Crash Rate at FT050, Jalan Batu Pahat – Kluang: Pre and Post Road Median Divider Joewono Prasetijo1,*, Nurhafidz Abd Rahaman1, Nor Baizura Hamid1, Nurfarhanna Ahmad Sulaiman1, Muhammad Isradi2, Maisara Ashran Mustafa3, Zulhaidi Mohd Jawi4 & Zulhilmi Zaidie5 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1Sustainable Transport and Safety Studies (STSS), Faculty of Engineering Technology, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, 84600 Panchor, Johor, Malaysia 2Department of Civil Engineering, Universitas Mercu Buana, Jatisampurna, Bekasi, Jawa Barat 17433, Indonesia 3Department of Road Safety Malaysia (JKJR) Johor, Suite 25.01, Johor Bahru City Square, 80000 Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia 4Malaysian Institute of Road Safety Research (MIROS), Lot 125-135, Jalan TKS 1, 43000 Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia. 5Department of Road Transport Malaysia (JPJ), 83300 Batu Pahat, Johor, Malaysia ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO _____________________________________________________________________ ___________________________ The number of fatal crashes along the Federal Road FT050 (Jalan Batu Pahat – Kluang – Ayer Article -

The London Gazette of FRIDAY, Ipth OCTOBER, 1948 Bubllsljrti Bp Sunjotttp Registered As a Newspaper

ttumfc 38446 SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette OF FRIDAY, ipth OCTOBER, 1948 Bubllsljrti bp Sunjotttp Registered as a Newspaper TUESDAY, 2 NOVEMBER, 1948 War Office, 2nd November, 1948. The Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Maj. M. MOORE, M.C. (63764). The KING has been graciously pleased to confer Capt. (T/Maj.) C. D. WELLICOME (93438) the "Efficiency Decoration" upon the following (T.A.R.O.). officers of the Territorial Army:— The Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's ROYAL ARMOURED CORPS. Own Yorkshire Regiment). Royal Tank Regiment. Capt. (Hon. Maj.) G. N. GIRLING (63187). Maj. J. R. N. BELL (63697). The King's Own Scottish Borderers. Maj. F. G. FOLEY (63081). Capt. G. W. JENKINS (49464) (T.A.R.O.). Capt. (Hon. Maj.) W. F. WEBB (53304). The Border Regiment. Capt. F. A. SKELTON (26115) (T.A.R.O.). Capt. R. W. HIND (53806). ROYAL ARTILLERY. The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment). Lt-Col. D. C. ALDRIDGE (56291). Maj. M. G. NAIRN (58334). Lt.-Col. S. S. ROBINSON, M.B.E. (66552). The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) F. B. C. COOKE, O.B.E. Derbyshire Regiment). (28495). Maj. E. H. STAFFORD (63237). Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) H. J. GILLMAN (37913). Capt. (Hon. Maj.) J. KIRKLAND (24891). Maj. J. DEMPSTER (56399). Maj. M. T. GAMBLING (62237). The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge's Maj. J. A. G. KERR (62047). Own). Maj. C. L. A. MADELEY (20098). Maj. R. T. D. HICKS (70697). Maj. E. A. MILTON (20618) (Died of Wounds). The York and Lancaster Regiment. Maj. E. C. -

SUFFOLK REGIMENT ASSOCIATION Records, 1972-74 Reel M973

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SUFFOLK REGIMENT ASSOCIATION Records, 1972-74 Reel M973 Suffolk Regiment Association The Keep Gibraltar Barracks Bury St Edmunds Suffolk IP33 3RN National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1976 HISTORICAL NOTE The Suffolk Regiment was raised by the Duke of Norfolk in 1685 to combat the Monmouth Rebellion and comprised men from the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. Originally known as the Duke of Norfolk’s Regiment of Foot, it was renamed the 12th Regiment of Foot in 1751. In 1782 it was called the 12th (East Suffolk) Regiment of Foot and in 1880 it became the 12th (Suffolk) Regiment. It saw action in Ireland (1689-91) and in Europe in the War of Austrian Succession (1742-45) and the Seven Years War (1758-62). During the Napoleonic Wars it served in the West Indies, India and Mauritius. In 1854 the 1st Battalion of the 12th Regiment sailed to Australia, where it was based at Sydney. Shortly after its arrival, a detachment was sent to Port Phillip and it took part in the fighting at the Eureka Stockade in Ballarat on 3 December 1854. During their time in Australia, soldiers of the 12th Regiment often acted as convict guards. In April 1860 two companies of the 12th Regiment and half a battery of artillery were sent to New Zealand, where they served under Major General Thomas Pratt in fighting against Maori forces. In 1862 the headquarters of the battalion were transferred to Auckland and the remaining companies moved from Australia to New Zealand. -

BIL DAERAH MUKIM NO. LOT LUAS (Ha.) 1 MERSING JEMALUANG 10

DATA TANAH TERBIAR TAHUN 2019 NEGERI: JOHOR BIL DAERAH MUKIM NO. LOT LUAS (Ha.) 1 MERSING JEMALUANG 10 1.25 2 MERSING JEMALUANG 1004 0.81 3 MERSING JEMALUANG 1010 0.82 4 MERSING JEMALUANG 1039 1.05 5 MERSING JEMALUANG 1040 1.52 6 MERSING JEMALUANG 1053 11.03 7 MERSING JEMALUANG 1065 0.59 8 MERSING JEMALUANG 1066 0.58 9 MERSING JEMALUANG 1072 0.82 10 MERSING JEMALUANG 1078 1.10 11 MERSING JEMALUANG 1079 1.50 12 MERSING JEMALUANG 108 0.62 13 MERSING JEMALUANG 1083 0.76 14 MERSING JEMALUANG 1092 0.53 15 MERSING JEMALUANG 1095 0.88 16 MERSING JEMALUANG 1096 0.90 17 MERSING JEMALUANG 1097 1.05 18 MERSING JEMALUANG 1098 0.81 19 MERSING JEMALUANG 1099 0.89 20 MERSING JEMALUANG 11 0.83 21 MERSING JEMALUANG 110 0.96 22 MERSING JEMALUANG 1100 0.66 23 MERSING JEMALUANG 1101 1.18 24 MERSING JEMALUANG 1103 0.58 25 MERSING JEMALUANG 1104 0.76 26 MERSING JEMALUANG 1106 1.35 27 MERSING JEMALUANG 1332 16.75 28 MERSING JEMALUANG 157 0.70 29 MERSING JEMALUANG 1851 0.81 30 MERSING JEMALUANG 1852 0.66 31 MERSING JEMALUANG 1856 0.80 32 MERSING JEMALUANG 1858 0.81 33 MERSING JEMALUANG 1859 0.81 34 MERSING JEMALUANG 1860 0.81 35 MERSING JEMALUANG 1861 0.81 36 MERSING JEMALUANG 1862 0.81 37 MERSING JEMALUANG 1863 0.81 38 MERSING JEMALUANG 1864 0.81 39 MERSING JEMALUANG 1865 0.80 40 MERSING JEMALUANG 1867 0.82 41 MERSING JEMALUANG 1868 0.82 42 MERSING JEMALUANG 1869 0.76 43 MERSING JEMALUANG 1870 0.76 44 MERSING JEMALUANG 1871 0.83 45 MERSING JEMALUANG 1872 0.76 46 MERSING JEMALUANG 1873 0.85 47 MERSING JEMALUANG 1874 0.83 48 MERSING JEMALUANG 1877 0.82 49 MERSING JEMALUANG 1878 0.82 - 1 - DATA TANAH TERBIAR TAHUN 2019 NEGERI: JOHOR BIL DAERAH MUKIM NO. -

![Infantry Division (1944-45)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3851/infantry-division-1944-45-1503851.webp)

Infantry Division (1944-45)]

20 November 2019 [59 (STAFFORDSHIRE) INFANTRY DIVISION (1944-45)] th 59 (Staffordshire) Infantry Division (1) Divisional Headquarters, 3rd Infantry Division Headquarters Defence & Employment Platoon 26th Field Security Section, Intelligence Corps 176th Infantry Brigade (2) Headquarters, 176th Infantry Brigade, Signal Section & Light Aid Detachment 7th Bn. The South Staffordshire Regiment 6th Bn. The North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s) 7th Bn. The Royal Norfolk Regiment 177th Infantry Brigade (3) Headquarters, 177th Infantry Brigade, Signal Section & Light Aid Detachment 5th Bn. The South Staffordshire Regiment 1st/6th Bn. The South Staffordshire Regiment 2nd/6th Bn. The South Staffordshire Regiment 197th Infantry Brigade (4) Headquarters, 197th Infantry Brigade, Signal Section & Light Aid Detachment 2nd/5th Bn. The Lancashire Fusiliers 5th Bn. The East Lancashire Regiment 1st/7th Bn. The Royal Warwickshire Regiment Divisional Troops 59th Reconnaissance Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (5) 7th Bn. The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (6) ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 20 November 2019 [59 (STAFFORDSHIRE) INFANTRY DIVISION (1944-45)] Headquarters, 59th (Staffordshire) Divisional Royal Artillery 61st (North Midland) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (7) 110th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (8) 116th (North Midland) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (8) 68th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (9) 68th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery (10) Headquarters, 59th (Staffordshire) Divisional Royal Engineers 257th -

1970 Population Census of Peninsular Malaysia .02 Sample

1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE DATA DOCUMENTATION AND CODEBOOK 1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE CONTENTS Page TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON THE DATA TAPE 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA FILE 2 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1: HOUSEHOLD RECORD 4 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2: PERSON RECORD (AGE BELOW 10) 5 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3: PERSON RECORD (AGE 10 AND ABOVE) 6 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1 7 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2 15 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3 24 APPENDICES: A.1: Household Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 4) 33 A.2: Individual Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 5) 34 B.1: List of State and District Codes 35 B.2: List of Codes of Local Authority (Cities and Towns) Codes within States and Districts for States 38 B.3: "Cartographic Frames for Peninsular Malaysia District Statistics, 1947-1982" by P.P. Courtenay and Kate K.Y. Van (Maps of Adminsitrative district boundaries for all postwar censuses). 70 C: Place of Previous Residence Codes 94 D: 1970 Population Census Occupational Classification 97 E: 1970 Population Census Industrial Classification 104 F: Chinese Age Conversion Table 110 G: Educational Equivalents 111 H: R. Chander, D.A. Fernadez and D. Johnson. 1976. "Malaysia: The 1970 Population and Housing Census." Pp. 117-131 in Lee-Jay Cho (ed.) Introduction to Censuses of Asia and the Pacific, 1970-1974. Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Population Institute. -

Johor 81900 Kota Tinggi

Bil. Bil Nama Alamat Daerah Dun Parlimen Kelas BLOK B BLOK KELICAP PUSAT TEKNOLOGI TINGGI ADTEC JALAN 1 TABIKA KEMAS ADTEC Batu Pahat Senggarang Batu Pahat 1 TANJONG LABOH KARUNG BERKUNCI 527 83020 BATU PAHAT Tangkak (Daerah 2 TABIKA KEMAS DEWAN PUTERA JALAN JAAMATKG PADANG LEREK 1 80900 TANGKAK Tangkak Ledang 1 Kecil) 3 TABIKA KEMAS FELDA BUKIT BATU FELDA BUKIT BATU 81020 KULAI Kulai Jaya Bukit Batu Kulai 1 Bukit 4 TABIKA KEMAS KG TUI 2 TABIKA KEMAS KG. TUI 2 BUKIT KEPONG 84030 BUKIT KEPONG Muar Pagoh 1 Serampang BALAI RAYAKAMPUNG PARIT ABDUL RAHMANPARIT SULONG 5 TABIKA KEMAS PT.HJ ABD RAHMAN Batu Pahat Sri Medan Parit Sulong 1 83500 BATU PAHAT 6 TABIKA KEMAS PUTRA JL 8 JALAN LAMA 83700 YONG PENG Batu Pahat Yong Peng Ayer Hitam 2 7 TABIKA KEMAS SERI BAYU 1 NO 12 JALAN MEWAH TAMAN MEWAH 83700 YONG PENG Batu Pahat Yong Peng Ayer Hitam 1 39 JALAN BAYU 14 TAMAN SERI BAYU YONG PENG 83700 BATU 8 TABIKA KEMAS SERI BAYU 2 Batu Pahat Yong Peng Ayer Hitam 1 PAHAT TABIKA KEMAS TAMAN BUKIT NO 1 JALAN GEMILANG 2/3A TAMAN BUKIT BANANG 83000 BATU 9 Batu Pahat Senggarang Batu Pahat 1 BANANG PAHAT 10 TABIKA KEMAS TAMAN HIDAYAT BALAI SERBAGUNA TAMAN HIDAYAT 81500 PEKAN NANAS Pontian Pekan Nanas Tanjong Piai 1 11 TABIKA KEMAS TAMAN SENAI INDAH JALAN INDAH 5 TAMAN SENAI INDAH 81400 SENAI Kulai Jaya Senai Kulai 1 TABIKA KEMAS ( JAKOA ) KG SRI BALAI TABIKA KEMAS JAKOA KAMPUNG SRI DUNGUN 82000 12 Pontian Pulai Sebatang Pontian 2 DUNGUN PONTIAN 13 TABIKA KEMAS (JAKOA ) KG BARU TABIKA JAKOA KG BARU KUALA BENUT 82200 PONTIAN Pontian Benut Pontian 1 14 TABIKA -

View Document

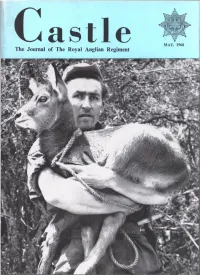

We did not capture the CASTLE we printed it! We cannot win your battles, but we will help you plan your campaign. PRIN TIN G is our business. We produce books, magazines, brochures, leaflets and business stationery. Our advice on all technical problems and fully prepared estimates are absolutely free. Our plant at Bedford is ideally situated for communications through out the country. DIEMER & REYNOLDS LTD Letterpress and Lithographic Printers EASTCOTTS ROAD, BEDFORD Telephone 0234-51251/2/3/4 5/68-1 Printed in Great Britain SUPPLEMENT No. 1-PAGE ONE CONWAY WILLIAMS THE MAYFAIR TAILOR 48 BROOK STREET, MAYFAIR, LONDON, W.1 (Opposite Claridges Hotel) AND 39 LONDON ROAD, CAMBERLEY Morning and Evening Wear, Court and Military Dress for all occasions. Hunting, Sports and Lounge Kits All Cloths cut by expert West End Cutters and made exclusively by hand in our Mayfair workshops by the Best English Tailors Regimental Tailors to The Royal Anglian Regiment Telephones: Telegrams: Mayfair 0945—Camberley 498. “ Militailia Wesdo, London ” MAC’S N o 1 Good Country A sight to see in Britain? Yes. You can spend a very comfortable night here too. It's one of sixty Ind Coope Hotels you can stay in throughout Britain. Call it charm, service, comfort or what you will, these hotels have a distinctly congenial atmosphere which you will enjoy and remember It makes it worth your while to spend a few nights in an Ind Coope Hotel It’s a sight to see. For a colour brochure showing photographs, rates and loca tions of Ind Coope Hotels, simply post this coupon on the right. -

Japs' Army Now Closer Tcysingapore

CitgwiMg Hgfalii Mra. John J. O’Brien, tba form Portland, Malnt, tha latter part of Wherever the U. S. Stands Guard, the Red Cross Fla^ Waves! 8 t Bridcet’a church women will Richard Brannick, eon o f Mr. Charles Crockett baa made a request for deputy air raid war er Misa Edith Thesher, was honor November, has been called back meet tomorrow afternoon at 1:30 and Mrs. P. R. Brtumlck of Oak dens In his sector, which Includes ed with a personal shower Friday to the service and ia to report About Town In the parish hall and i ^ n on land atreet, left thia morning for the Highland Park ariea. Any per for duty tomorrow. Wednesday evening at 7:30, to Camp Devena, and expects within evening by 26 of her relatives and a day or two to leave for Jefferaon son, living on Gardner atreet or friendfl. The hostesses were Mrs. Average Daily Clrcalatlon lacotMl ContTC(KUon«I sew for the Red Cross. Anyone Last Week Of Hale’s Birch MountaJk -Road who is w ill For Um Month of Ooeomber, IM l having scraps of yam for use In City, Mo. The ^oung man ie a George McKay, Miss Judy'JaUsn- r 4ta K h choir club wlU hav* a party ing to do hla part In national de knitting afgban squares should graduate of Manchester High der and Miaa Mary Fay, and the ♦Mm ^vaniiic at 6:30 at the T. M- fense, la asked to get In touch with bring them to these meetings. -

Royal Norfolk Regiment Collection, Norwich Castle

Material Encounters Catalogue 2016 I. Collections Level Description Department: Royal Norfolk Regiment Collection, Norwich Castle Collection Type: Tibetan Collection Reference: NWHRM.COLLECTION No. of items: 21 Notes Date of research visit: 14th May 2014 Contact: Kate Thaxton, Curator ‘Serving the Empire: The regiment around the world’ Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum Collection display in Norwich Castle 'Treasure, Trade and the Exotic’ display in Norwich Castle 1 | P a g e Material Encounters Catalogue 2016 Musket [NWHRM.1270] © Royal Norfok Regiment, Norwich Sword [NWHRM.3067] © Royal Norfok Regiment, Norwich Flint and tinder pouch [NWHRM.3068] © Royal Norfok Regiment, Norwich Hand held prayer wheel [NWHRM.3069] © Royal Norfok Regiment, Norwich Ceremonial axe [NWHRM.3071] © Royal Norfok Regiment, Norwich Category Religion and ritual Weapons Loot Archival Photographs Description INTRODUCTION: The Royal Norfolk Regiment no longer have their own museum, instead objects from their collection are now (since Oct 2013) displayed in Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery. The regimental collection office is situated in the Norwich Castle 2 | P a g e Material Encounters Catalogue 2016 Study Centre. The collection of material that they have which relates to the Younghusband Mission to Tibet is incredibly coherent as the objects, photographs and archival material all came related to one person - Lt. Col. Arthur Lovell Hadow (1877-1968) who served in Machine Gun Section of the 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment. As a result this collection provides a very comprehensive insight into military collecting practices in Tibet during this campaign. OBJECTS: There are 16 objects in total which were brought back by soldier’s serving in Tibet during the Younghusband Mission.