Histology and Affinity of Anaspids, and the Early Evolution of the Vertebrate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Phylum Tardigrada - Review

Volume V, Issue V, May 2016 IJLTEMAS ISSN 2278 – 2540 An Introduction to phylum Tardigrada - Review Yashas R Devasurmutt1, Arpitha B M1* 1: R & D Centre, Department of Biotechnology, Dayananda Sagar College of Engineering, Bangalore, India 1*: Corresponding Author: Arpitha B M Abstract: Tardigrades popularly known as water bears are In cryptobiosis (extreme form of anabiosis), the metabolism is micrometazoans with four pairs of lobopod legs. They are the undetectable and the animal is known as tun in this phase. organisms which can live in extreme conditions and are known to Tuns have been known to survive very harsh environmental survive in vacuum and space without protection. Tardigardes conditions such as immersion in helium at -272° C (-458° F) survive in lichens and mosses, usually associated with water film or heating temperatures at 149° C (300° F), exposure to very on mosses, liverworts, and lichens. More species are found in high ionizing radiation and toxic chemical substances and milder environments such as meadows, ponds and lakes. They long durations without oxygen. [4] Figure 2 illustrates the are the first known species to survive in outer space. Tardigrades process of transition of the tardigrades[41]. are closely related to Arthropoda and nematodes based on their morphological and molecular analysis. The cryptobiosis of Figure 2: Transition process of Tardigrades Tardigrades have helped scientists to develop dry vaccines. They have been applied as research subjects in transplantology. Future research would help in more applications of tardigrades in the field of science. Keywords: Tardigrades, cryptobiosis, dry vaccines, Transplantology, space research I. INTRODUCTION ardigrade, a group of tiny arthropod-like animals having T four pairs of stubby legs with big claws, an oval stout body with a round back and lumbering gait. -

Origin and Beyond

EVOLUTION ORIGIN ANDBEYOND Gould, who alerted him to the fact the Galapagos finches ORIGIN AND BEYOND were distinct but closely related species. Darwin investigated ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE (1823–1913) the breeding and artificial selection of domesticated animals, and learned about species, time, and the fossil record from despite the inspiration and wealth of data he had gathered during his years aboard the Alfred Russel Wallace was a school teacher and naturalist who gave up teaching the anatomist Richard Owen, who had worked on many of to earn his living as a professional collector of exotic plants and animals from beagle, darwin took many years to formulate his theory and ready it for publication – Darwin’s vertebrate specimens and, in 1842, had “invented” the tropics. He collected extensively in South America, and from 1854 in the so long, in fact, that he was almost beaten to publication. nevertheless, when it dinosaurs as a separate category of reptiles. islands of the Malay archipelago. From these experiences, Wallace realized By 1842, Darwin’s evolutionary ideas were sufficiently emerged, darwin’s work had a profound effect. that species exist in variant advanced for him to produce a 35-page sketch and, by forms and that changes in 1844, a 250-page synthesis, a copy of which he sent in 1847 the environment could lead During a long life, Charles After his five-year round the world voyage, Darwin arrived Darwin saw himself largely as a geologist, and published to the botanist, Joseph Dalton Hooker. This trusted friend to the loss of any ill-adapted Darwin wrote numerous back at the family home in Shrewsbury on 5 October 1836. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

Palaeontology, 2010, Pp

PALA 1019 Dispatch: 15.10.10 Journal: PALA CE: Archana Journal Name Manuscript No. B Author Received: No. of pages: 17 PE: Raymond [Palaeontology, 2010, pp. 1–17] 1 2 3 TAPHONOMY AND AFFINITY OF AN ENIGMATIC 4 5 SILURIAN VERTEBRATE, JAMOYTIUS KERWOODI 6 7 WHITE 8 9 by ROBERT S. SANSOM*, KIM FREEDMAN* , SARAH E. GABBOTT*, 10 RICHARD J. ALDRIDGE* and MARK A. PURNELL* 11 *Department of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; e-mails [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], 12 [email protected] 13 6 Wescott Road, Wokingham, Berkshire RG40 2ES, UK; e-mail [email protected] 14 Typescript received 14 July 2009; accepted in revised form 23 April 2010 15 16 17 Abstract: The anatomy and affinities of Jamoytius kerwoodi pairs of branchial openings, optic capsules, a circular, subter- 18 White have long been controversial, because its complex minal mouth and a single terminal nasal opening. Interpreta- 19 taphonomy makes unequivocal interpretation impossible tions of paired ‘appendages’ remain equivocal. Phylogenetic 20 with the methodology used in previous studies. Topological analysis places Jamoytius and Euphanerops together (Jamoytii- 21 analysis, model reconstruction and elemental analysis, fol- formes), as stem-gnathostomes rather than lamprey related 22 lowed by anatomical interpretation, allow features to be or sister taxon to Anaspida. 23 identified more rigorously and support the hypothesis that 24 Jamoytius is a jawless vertebrate. The preserved features of Key words: Jamoytius, Euphanerops, phylogeny, taphonomy, 25 Jamoytius include W-shaped phosphatic scales, 10 or more Vertebrata, Gnathostomata, Silurian. -

LETTER Doi:10.1038/Nature13414

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13414 A primitive fish from the Cambrian of North America Simon Conway Morris1 & Jean-Bernard Caron2,3 Knowledge of the early evolution of fish largely depends on soft- (Extended Data Fig. 4f). Incompleteness precludes a precise estimate of bodied material from the Lower (Series 2) Cambrian period of South size range, but themostcomplete specimens (Fig.1a,b) areabout 60 mm China1,2. Owing to the rarity of some of these forms and a general in length and 8–13 mm in height. Laterally the body is fusiform, widest lack of comparative material from other deposits, interpretations of near the middle, tapering to a fine point posteriorly (Fig. 1a, b and Ex- various features remain controversial3,4, as do their wider relation- tended Data Fig. 4a), whereas in dorsal view the anterior termination is ships amongst post-Cambrian early un-skeletonized jawless verte- rounded (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 4c–e). The animal was com- brates. Here we redescribe Metaspriggina5 on the basis of new material pressed laterally, as is evident from occasional folding of the body as well from the Burgess Shale and exceptionally preserved material collected as specimensindorso-ventral orientation being conspicuously narrower near Marble Canyon, British Columbia6, and three other Cambrian (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Along the anterior ventral margin Burgess Shale-type deposits from Laurentia. This primitive fish dis- there was a keel-like structure (Fig. 1b, g, i, k, l), but no fins have been plays unambiguous vertebrate features: a notochord, a pair of prom- recognized. In the much more abundant specimens of Haikouichthys1,3,4 inent camera-type eyes, paired nasal sacs, possible cranium and arcualia, fins are seldom obvious, suggesting that their absence in Metaspriggina W-shaped myomeres, and a post-anal tail. -

Ecdysis in a Stem-Group Euarthropod from the Early Cambrian of China Received: 2 November 2018 Jie Yang1,2, Javier Ortega-Hernández 3,4, Harriet B

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Ecdysis in a stem-group euarthropod from the early Cambrian of China Received: 2 November 2018 Jie Yang1,2, Javier Ortega-Hernández 3,4, Harriet B. Drage5,6, Kun-sheng Du1,2 & Accepted: 20 March 2019 Xi-guang Zhang1,2 Published: xx xx xxxx Moulting is a fundamental component of the ecdysozoan life cycle, but the fossil record of this strategy is susceptible to preservation biases, making evidence of ecdysis in soft-bodied organisms extremely rare. Here, we report an exceptional specimen of the fuxianhuiid Alacaris mirabilis preserved in the act of moulting from the Cambrian (Stage 3) Xiaoshiba Lagerstätte, South China. The specimen displays a fattened and wrinkled head shield, inverted overlap of the trunk tergites over the head shield, and duplication of exoskeletal elements including the posterior body margins and telson. We interpret this fossil as a discarded exoskeleton overlying the carcass of an emerging individual. The moulting behaviour of A. mirabilis evokes that of decapods, in which the carapace is separated posteriorly and rotated forward from the body, forming a wide gape for the emerging individual. A. mirabilis illuminates the moult strategy of stem-group Euarthropoda, ofers the stratigraphically and phylogenetically earliest direct evidence of ecdysis within total-group Euarthropoda, and represents one of the oldest examples of this growth strategy in the evolution of Ecdysozoa. Te process of moulting consists of the periodical shedding (i.e. ecdysis) of the cuticular exoskeleton during growth that defnes members of Ecdysozoa1, a megadiverse animal group that includes worm-like organisms with radial mouthparts (Priapulida, Loricifera, Nematoida, Kinorhyncha), as well as more familiar forms with clawed paired appendages (Euarthropoda, Tardigrada, Onychophora). -

Hallucigenia's Onychophoran-Like Claws

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13576 Hallucigenia’s onychophoran-like claws and the case for Tactopoda Martin R. Smith1 & Javier Ortega-Herna´ndez1 The Palaeozoic form-taxon Lobopodia encompasses a diverse range of Onychophorans lack armature sclerites, but possess two types of ap- soft-bodied‘leggedworms’ known from exceptionalfossil deposits1–9. pendicular sclerite: paired terminal claws in the walking legs, and den- Although lobopodians occupy a deep phylogenetic position within ticulate jaws within the mouth cavity9,23.AsinH. sparsa, claws in E. Panarthropoda, a shortage of derived characters obscures their evo- kanangrensis exhibit a broad base that narrows to a smooth conical point lutionary relationships with extant phyla (Onychophora, Tardigrada (Fig. 1e–h). Each terminal clawsubtends anangle of130u and comprises and Euarthropoda)2,3,5,10–15. Here we describe a complex feature in two to three constituent elements (Fig. 1e–h). Each smaller element pre- the terminal claws of the mid-Cambrian lobopodian Hallucigenia cisely fills the basal fossa of its container, from which it can be extracted sparsa—their construction from a stack of constituent elements— with careful manipulation (Fig. 1e, g, h and Extended Data Fig. 3a–g). and demonstrate that equivalent elements make up the jaws and claws Each constituent element has a similar morphology and surface orna- of extant Onychophora. A cladistic analysis, informed by develop- ment (Extended Data Fig. 3a–d), even in an abnormal claw where mental data on panarthropod head segmentation, indicates that the element tips are flat instead of pointed (Extended Data Fig. 3h). The stacked sclerite components in these two taxa are homologous— proximal bases of the innermost constituent elements are associated with resolving hallucigeniid lobopodians as stem-group onychophorans. -

Fossil Calibrations for the Arthropod Tree of Life

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/044859; this version posted June 10, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. FOSSIL CALIBRATIONS FOR THE ARTHROPOD TREE OF LIFE AUTHORS Joanna M. Wolfe1*, Allison C. Daley2,3, David A. Legg3, Gregory D. Edgecombe4 1 Department of Earth, Atmospheric & Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 2 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 3 Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PZ, UK 4 Department of Earth Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Fossil age data and molecular sequences are increasingly combined to establish a timescale for the Tree of Life. Arthropods, as the most species-rich and morphologically disparate animal phylum, have received substantial attention, particularly with regard to questions such as the timing of habitat shifts (e.g. terrestrialisation), genome evolution (e.g. gene family duplication and functional evolution), origins of novel characters and behaviours (e.g. wings and flight, venom, silk), biogeography, rate of diversification (e.g. Cambrian explosion, insect coevolution with angiosperms, evolution of crab body plans), and the evolution of arthropod microbiomes. We present herein a series of rigorously vetted calibration fossils for arthropod evolutionary history, taking into account recently published guidelines for best practice in fossil calibration. -

Fossils Provide Better Estimates of Ancestral Body Size Than Do Extant

Acta Zoologica (Stockholm) 90 (Suppl. 1): 357–384 (January 2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00364.x FossilsBlackwell Publishing Ltd provide better estimates of ancestral body size than do extant taxa in fishes James S. Albert,1 Derek M. Johnson1 and Jason H. Knouft2 Abstract 1Department of Biology, University of Albert, J.S., Johnson, D.M. and Knouft, J.H. 2009. Fossils provide better Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA estimates of ancestral body size than do extant taxa in fishes. — Acta Zoologica 2 70504-2451, USA; Department of (Stockholm) 90 (Suppl. 1): 357–384 Biology, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO, USA The use of fossils in studies of character evolution is an active area of research. Characters from fossils have been viewed as less informative or more subjective Keywords: than comparable information from extant taxa. However, fossils are often the continuous trait evolution, character state only known representatives of many higher taxa, including some of the earliest optimization, morphological diversification, forms, and have been important in determining character polarity and filling vertebrate taphonomy morphological gaps. Here we evaluate the influence of fossils on the interpretation of character evolution by comparing estimates of ancestral body Accepted for publication: 22 July 2008 size in fishes (non-tetrapod craniates) from two large and previously unpublished datasets; a palaeontological dataset representing all principal clades from throughout the Phanerozoic, and a macroecological dataset for all 515 families of living (Recent) fishes. Ancestral size was estimated from phylogenetically based (i.e. parsimony) optimization methods. Ancestral size estimates obtained from analysis of extant fish families are five to eight times larger than estimates using fossil members of the same higher taxa. -

Draft Genome of the Heterotardigrade Milnesium Tardigradum Sheds Light on Ecdysozoan Evolution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/122309; this version posted September 4, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Draft genome of the Heterotardigrade Milnesium tardigradum sheds light on ecdysozoan evolution Felix Bemm1,2*, Laura Burleigh3, Frank Förster1,4, Roland Schmucki5, Martin Ebeling5, Christian J. Janzen6, Thomas Dandekar1, Ralph O. Schill7, Ulrich Certa5, Jörg Schultz1,4 1 Department of Bioinformatics, University Würzburg, 97074 Würzburg, Germany 2 Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, 72076 Tübingen, Germany 3 Roche Products Limited, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom 4 Center for Computational and Theoretical Biology (CCTB), 97074 Würzburg, Germany 5 Pharmaceutical Sciences, Roche Pharma Research and Early Development, Roche Innovation Center Basel, 124 Grenzacherstrasse, Basel CH 4070, Switzerland 6 Department of Zoology I, Biocenter, University Würzburg, 97074 Würzburg, Germany 7 Institute of Biomaterials and biomolecular Systems, 70174 Stuttgart, Germany * E-Mail: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/122309; this version posted September 4, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Tardigrades are among the most stress tolerant animals and survived even unassisted exposure to space in low earth orbit. Still, the adaptations leading to these unusual physiological features remain unclear. -

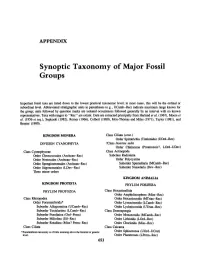

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The palaeobiology of the panderodontacea and selected other euconodonts Sansom, Ivan James How to cite: Sansom, Ivan James (1992) The palaeobiology of the panderodontacea and selected other euconodonts, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5743/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubHshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. THE PALAEOBIOLOGY OF THE PANDERODONTACEA AND SELECTED OTHER EUCONODONTS Ivan James Sansom, B.Sc. (Graduate Society) A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Durham Department of Geological Sciences, July 1992 University of Durham. 2 DEC 1992 Contents CONTENTS CONTENTS p. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS p. viii DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT p.