1.0 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2: Baseline, Section 13: Traditional Land Use September 2011 Volume 2: Baseline Studies Frontier Project Section 13: Traditional Land Use

R1 R24 R23 R22 R21 R20 T113 R19 R18 R17 R16 Devil's Gate 220 R15 R14 R13 R12 R11 R10 R9 R8 R7 R6 R5 R4 R3 R2 R1 ! T112 Fort Chipewyan Allison Bay 219 T111 Dog Head 218 T110 Lake Claire ³ Chipewyan 201A T109 Chipewyan 201B T108 Old Fort 217 Chipewyan 201 T107 Maybelle River T106 Wildland Provincial Wood Buffalo National Park Park Alberta T105 Richardson River Dunes Wildland Athabasca Dunes Saskatchewan Provincial Park Ecological Reserve T104 Chipewyan 201F T103 Chipewyan 201G T102 T101 2888 T100 Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park T99 1661 850 Birch Mountains T98 Wildland Provincial Namur River Park 174A 33 2215 T97 94 2137 1716 T96 1060 Fort McKay 174C Namur Lake 174B 2457 239 1714 T95 21 400 965 2172 T94 ! Fort McKay 174D 1027 Fort McKay Marguerite River 2006 Wildland Provincial 879 T93 771 Park 772 2718 2926 2214 2925 T92 587 2297 2894 T91 T90 274 Whitemud Falls T89 65 !Fort McMurray Wildland Provincial Park T88 Clearwater 175 Clearwater River T87Traditional Land Provincial Park Fort McKay First Nation Gregoire Lake Provincial Park T86 Registered Fur Grand Rapids Anzac Management Area (RFMA) Wildland Provincial ! Gipsy Lake Wildland Park Provincial Park T85 Traditional Land Use Regional Study Area Gregoire Lake 176, T84 176A & 176B Traditional Land Use Local Study Area T83 ST63 ! Municipality T82 Highway Stony Mountain Township Wildland Provincial T81 Park Watercourse T80 Waterbody Cowper Lake 194A I.R. Janvier 194 T79 Wabasca 166 Provincial Park T78 National Park 0 15 30 45 T77 KILOMETRES 1:1,500,000 UTM Zone 12 NAD 83 T76 Date: 20110815 Author: CES Checked: DC File ID: 123510543-097 (Original page size: 8.5X11) Acknowledgements: Base data: AltaLIS. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 30th Legislature Second Session Alberta Hansard Monday afternoon, July 20, 2020 Day 47 The Honourable Nathan M. Cooper, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 30th Legislature Second Session Cooper, Hon. Nathan M., Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (UCP), Speaker Pitt, Angela D., Airdrie-East (UCP), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Milliken, Nicholas, Calgary-Currie (UCP), Deputy Chair of Committees Aheer, Hon. Leela Sharon, Chestermere-Strathmore (UCP) Nally, Hon. Dale, Morinville-St. Albert (UCP) Allard, Tracy L., Grande Prairie (UCP) Deputy Government House Leader Amery, Mickey K., Calgary-Cross (UCP) Neudorf, Nathan T., Lethbridge-East (UCP) Armstrong-Homeniuk, Jackie, Nicolaides, Hon. Demetrios, Calgary-Bow (UCP) Fort Saskatchewan-Vegreville (UCP) Nielsen, Christian E., Edmonton-Decore (NDP) Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (UCP) Nixon, Hon. Jason, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (NDP), (UCP), Government House Leader Official Opposition Deputy House Leader Nixon, Jeremy P., Calgary-Klein (UCP) Carson, Jonathon, Edmonton-West Henday (NDP) Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (NDP), Ceci, Joe, Calgary-Buffalo (NDP) Leader of the Official Opposition Copping, Hon. Jason C., Calgary-Varsity (UCP) Orr, Ronald, Lacombe-Ponoka (UCP) Dach, Lorne, Edmonton-McClung (NDP) Pancholi, Rakhi, Edmonton-Whitemud (NDP) Dang, Thomas, Edmonton-South (NDP) Panda, Hon. Prasad, Calgary-Edgemont (UCP) Deol, Jasvir, Edmonton-Meadows (NDP) Dreeshen, Hon. Devin, Innisfail-Sylvan Lake (UCP) Phillips, Shannon, Lethbridge-West (NDP) Eggen, David, Edmonton-North West (NDP), Pon, Hon. Josephine, Calgary-Beddington (UCP) Official Opposition Whip Rehn, Pat, Lesser Slave Lake (UCP) Ellis, Mike, Calgary-West (UCP), Reid, Roger W., Livingstone-Macleod (UCP) Government Whip Renaud, Marie F., St. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

Syncrude Pathways 2015

ISSUE NO VI · SYNCRUDE CANADA LTD. ABORIGINAL REVIEW 2015 Truth and Veteran Nicole Astronomer Firefighter NHL Reconciliation welder Bourque- shares Cynthia player Jordin Commission Joe Lafond Bouchier’s Aboriginal Courteoreille Tootoo scores recommendations saves horses family ties perspectives blazes new trails in life 08 14 24 26 30 38 Welcome There are many different pathways to success. It could these stories and connects with First Nations and Métis be sculpting a work of art, preparing dry fish and listening people making positive contributions in their communities, to the wisdom of Elders. It could be studying for certification, bringing new perspectives to the table and influencing a college diploma or university degree. Or it could be change in our society. volunteering for a local not-for-profit organization. Join us as we explore these many diverse pathways There is no end to the remarkable successes and and learn how generations young and old are working accomplishments among Aboriginal people in our region, to make a difference. our province and across our country. Pathways captures THE STORIES in Pathways reflect the six key commitment areas of Syncrude’s Aboriginal Relations BUSINESS EMPLOYMENT program: Business Development, Wood Buffalo is home to some of the As one of the largest employers of Community Development, Education most successful Aboriginal businesses Aboriginal people in Canada, Syncrude’s and Training, Employment, the in Canada. Syncrude works closely goal is to create opportunities that Environment, and Corporate with Aboriginal business owners to enable First Nations, Métis and Inuit Leadership. As a representation identify opportunities for supplying people to fully participate in of our ongoing work with the local goods and services to our operation. -

Summer Student Success

A FORT MCKAY FIRST NATION PUBLICATION Current OCTOBER 2013 VOLUME 4 :: ISSUE 10 SUMMER STUDENT SUCCESS Summer is officially over and what a first aid, fatigue awareness, hygiene stellar one it was, especially for our and other life skills/job prepared- PARTNERSHIP 3 youth enrolled in the Summer Stu- ness workshops. BREAST CANCER dent Employment Program (SSEP). The youth were paid an hourly wage 4 All 26 youth, ages 14-18, completed and almost all chose the option to FMGOC JOB FAIR 5 and graduated from the program. have their pay banked with their The SSEP had a positive impact on final pay being matched by the BANNOCK EXPERTS 10 Fort McKay in many ways. It em- FMFN. The only ones that did not ROSE BUJOLD ployed the youth over the summer choose this option were those that 12 break, with their main job being the had living expenses that needed to HOCKEY 14 beautification of the community. be met, for example young mothers. The youth landscaped in the morn- A $500 bonus was also awarded to ings, with the Elders’ yards being those who were outstanding in the the first priority. In the summer areas of attendance, performance heat of the afternoons the youth and attitude towards work and the were either back working on Elders’ program. lawns or they attended an array of The students’ work experience and dynamic workshops including ATV their banked earnings were valu- safety, bear awareness, anti-bully- able, however, the life experience ing, WHMS, OHS, confined spaces, (Continued on page 2) 5 6 8 1 (Continued from page 1) CULTURAL EXPERIENCE AT MOOSE LAKE CAMP IS PRICELESS py to know how to erect a teepee now, and she “loved” how they all smudged every morning and every night. -

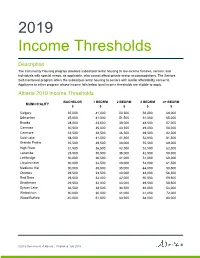

2019 Income Thresholds

2019 Income Thresholds Description The Community Housing program provides subsidized rental housing to low-income families, seniors, and individuals with special needs, as applicable, who cannot afford private sector accommodations. The Seniors Self-Contained program offers the subsidized rental housing to seniors with similar affordability concerns. Applicants to either program whose income falls below local income thresholds are eligible to apply. Alberta 2019 Income Thresholds BACHELOR 1 BEDRM 2 BEDRM 3 BEDRM 4+ BEDRM MUNICIPALITY $ $ $ $ $ Calgary 35,000 41,000 50,500 56,000 68,000 Edmonton 35,000 41,000 51,500 61,000 65,000 Brooks 28,000 33,500 38,000 48,500 57,000 Camrose 30,500 35,000 43,500 49,000 58,000 Canmore 33,500 38,500 46,500 69,500 82,000 Cold Lake 38,500 41,500 41,500 52,000 61,500 Grande Prairie 35,500 39,500 48,000 55,500 69,000 High River 31,500 36,500 42,500 52,500 62,000 Lacombe 25,500 30,500 36,000 42,500 50,000 Lethbridge 30,000 36,500 41,000 51,000 60,000 Lloydminister 30,000 34,500 48,000 52,000 61,500 Medicine Hat 30,000 30,500 35,000 44,000 50,500 Okotoks 29,500 33,500 40,000 48,000 56,500 Red Deer 29,500 34,000 42,000 50,500 59,500 Strathmore 29,500 34,000 43,000 49,500 58,500 Sylvan Lake 36,500 38,500 38,500 46,000 54,000 Wetaskiwin 30,000 30,000 41,000 61,000 72,000 Wood Buffalo 40,000 51,500 63,500 68,000 80,000 ©2019 Government of Alberta | Published: July 2019 BACHELOR 1 BEDRM 2 BEDRM 3 BEDRM 4+ BEDRM MUNICIPALITY $ $ $ $ $ Other Smaller Communities 31,000 35,500 40,000 43,500 54,000 Central Other Smaller -

Fort Mcmurray Books

Fort McMurray Branch, AGS: Library Resources 1 Resource Type Title Author Book "A Very Fine Class of Immigrants" Prince Edward Island's Scottish Pioneers 1770‐ Lucille H. Campey Book "Dit" Name: French‐Canadian Surnames, Aliases, Adulterations and Anglicizati, The Robert J. Quinton Book "Where the Redwillow Grew"; Valleyview and Surrounding Districts Valleyview and District Oldtimers Assoc. Book <New Title> Shannon Combs‐Bennett Book 10 Cemeteries, Stirling, Warner, Milk River & Coutts Area, Index Alberta Genealogical Society Book 10 Cemeteries,Bentley, Blackfalds, Eckville, Lacombe Area Alberta Genealogical Society Book 100 GENEALOGICAL REFERENCE WORKS ON MICROFICHE Johni Cerny & Wendy Elliot Book 100 Years of Nose Creek Valley History Sephen Wilk Book 100 Years The Royal Canadian Regiment 1883‐1983 Bell, Ken and Stacey, C.P. Book 11 Cemeteries Bashaw Ferintosh Ponoka Area, Index to Grave Alberta Genealogical Society Book 11 Cemeteries, Hanna, Morrin Area, Index to Grave Markers & Alberta Genealogical Society Book 12 Cemeteries Rimbey, Bluffton, Ponoka Area, Index to Grave Alberta Genalogical Society Book 126 Stops of Interest in British Columbia David E. McGill Book 16 Cemeteries Brownfield, Castor, Coronation, Halkirk Area, Index Alberta Genealogical Society Book 16 Cemeteries, Altario, Consort, Monitor, Veteran Area, Index to Alberta Genealogical Society Book 16 Cemeteries,Oyen,Acadia Valley, Loverna Area, Index Grave Alberta Genealogical Society Book 1666 Census for Nouvelle France Quintin Publications Book 1762 Census of the Government -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. -

2018 Municipal Codes

2018 Municipal Codes Updated November 23, 2018 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2018 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS / NAME CHANGES: 4353-Effective January 1, 2018 Lac La Biche County became the Specialized Municipality of Lac La Biche County. 0236-Effective February 28, 2018 Village of Nobleford became the Town of Nobleford. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: 6619- Effective April 10, 2018 Bonnyville Regional Water Services Commission formed as a Regional service commission. 6618- Effective April 10, 2018 South Pigeon Lake Regional Wastewater Services Commission formed as a Regional service commission. DISSOLVED: CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (6) 20 Services Commissions (73) 06 Municipal Districts (63) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (109) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (86) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (4) 08 Special Areas (4) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) November 23, 2018 Page 1 of 14 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

%ßjindspeaker Funded Annually Through Operated

DOROTHY SCHREIBER describes some job creation programs in her "In Touch" column. Page 14. PAULINE DEMPSEY is the winner of the first David Crowchild Memorial Award. Page 4. MARK McCALLUM has a lot to report in' Sports Roundup" as activities swing into high gear across the province. Page 13. Cu "threaten alcohol program By Rocky Woodward crisis situation in November or as human beings ?" At the January meeting, totally a avoiding the issue particular meeting held at of 1986, and now they no questioned Didzena. Didzena requested $12,000 --which is flexibility." Assumption. It hurt Didzena longer issue us our monthy Didzena says it is Today, January 14, the that "at least" to work with. "Maybe a neutral group to hear those words that in cash flow funeral of a young man was to operate the difficult for him to accept NNADAP promised them could be looked at. This actuality were deciding the program," people living in their held at Assumption. His commented rented $25,000 by January 19, way we could do away with fate of people who needed Didzena. towers that dictate him death was due to alcohol. to pending a financial report. the fantasy of policy. The help and support delivered On this same day, the Didzena believes the what he should do to better "They advance us the system just don't work," by the alcohol program. stoppage of funding started band manager for the Dena his people's lives because money and requesting our added Pelech. .his people. The Administration, Fred when NNADAP began to "they hold the purse cooperation, but nothing The funding was cut off Didzena, along with his identify areas of weaknesses strings." has changed. -

Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report

Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report Reporting Entity Name Cenovus Energy Inc Reporting Year From 2018-01-01 To: 2018-12-31 Date submitted 2019-05-29 Original Submission Reporting Entity ESTMA Identification Number E695282 Amended Report Other Subsidiaries Included (optional field) For Consolidated Reports - Subsidiary E179090 Cenovus FCCL Ltd, E543177 FCCL Partnership, E422918 Cenovus TL ULC, E540914 Telephone Lake Partnership, E435615 Cenovus Clearwater Partnership, E859468 Cenovus Elmworth Partnership, E724323 Cenovus Wapiti Partnership, Reporting Entities Included in Report: E461880 Cenovus Kaybob Partnership, E722884 Cenovus Edson Partnership Not Substituted Attestation by Reporting Entity In accordance with the requirements of the ESTMA, and in particular section 9 thereof, I attest I have reviewed the information contained in the ESTMA report for the entity(ies) listed above. Based on my knowledge, and having exercised reasonable diligence, the information in the ESTMA report is true, accurate and complete in all material respects for the purposes of the Act, for the reporting year listed above. Full Name of Director or Officer of Reporting Entity Jon McKenzie Date 2019-05-28 Position Title EVP & Chief Financial Officer Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act - Annual Report Reporting Year From: 2018-01-01 To: 2018-12-31 Reporting Entity Name Cenovus Energy Inc Currency of the Report CAD Reporting Entity ESTMA E695282 Identification Number Subsidiary Reporting Entities (if E179090 Cenovus FCCL Ltd, E543177 -

Historical Archives on the Métis Experience in Northeastern Alberta

Historical Archives on the Métis Experience in Northeastern Alberta April 2009 Prepared for Métis Local 1935 By Tereasa Maillie Métis in Northeastern Alberta Contents 1. Métis Trapline Research in Northeastern Alberta ............................................................................. - 2 - 1.1 Research Scope and Methods: .................................................................................................. - 2 - 1.2 Addendum to the Research Scope: ................................................................................................. - 3 - 2. Report on Findings: Provincial Archives of Alberta ......................................................................... - 4 - 2.1 Archival Sources of Information on Traplines, Trapping Licenses and Legislation ...................... - 4 - 2.2 Métis, Legislation, Métis Settlements ....................................................................................... - 5 - 2.3 Development of the Athabasca Oil Sands ....................................................................................... - 6 - 3. Report on Findings: University of Alberta Archives and Bruce Peel Special Collections ............... - 8 - 4. Recommendations for Further Research ......................................................................................... - 10 - 5. Annotated Bibliography .................................................................................................................. - 12 - 5.1 Holdings at the Provincial Archives of Alberta. ..........................................................................