T7^ Journal of the Rutgers University Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fate and Nature and the Creation of Tragic Sense in Some of Hardy's

ADAB AL-RAFIDAYN vol. (46) 1428 / 2007 Fate and Nature and the Creation of Tragic Sense in Some of Hardy’s Novels Ra’ad Ahmed Saleh(*) & Huda M. Saleh The indifference and hostility of Fate and Nature are the characterstic common in Hardy’s novels; inevitable suffering overwhelms the life of the character in Hardy’s novels. In his novels Fate and Nature rule the world of his novels. The hero’s desire for happiness collapses into terrible misery. Such an atmosphere makes Hardy’s novels of close relation to tragedies in the Greek sense. This means that Hardy’s novels can be considered the successors to the tragedies of the Greek, of Shakespeare and Marlowe before him. There are indications in the novels themselves that Hardy was attemping, in novel form, to present tragedies in the old model of Greek drama(1). (*)Assist. Professor Dept of English-College of Arts / University of Mosul. 37 Fate and Nature and the Creation of Tragic...... Ra’ad Ahmed Saleh & Huda M. Saleh It can be said of The Return of the Native, Tess of the D’Urbervills and The Mayor of Casterbridge that they conform to Aristotles’s definition of tragedies which is found in chapter six of his Poetics. He difined tragedy as: The imitation of an action that is serious, has magnitude, and is complete in itself in laguage with pleasurable accessories, each kind brought in separately in the various of the work; in a dramatic not in narrative form; with incidents arousing our pity and fear(2) Some people might feel discomfort to find novels compared to tragic play because they are written in narrative form. -

Manuscrits Littéraires Français Du Xxè Siècle

Ecole Nationale Superieure des Sciences de 1'information et des bibliotheques Diplome de conservateur de bibliotheque MEMOIRE D'ETUDE LES MAM S( RII S I.ITTKRAIRF.S FRANO AIS DV \\c SIFCl.F : C ONTF\TF F! MfSF E\ PLACF DTN RFPFRTOIRF DF LOCALISA 1ION Catherine ELOI Sous la direction de Madame Dominique BOUGE-GRANDON ENSSIB 1995 Ecole Nationale Superieure des Sciences de 1'information et des bibliotheques Diplome de conservateur de bibliotheque MEMOiRE D'ETUDE LF.S MAM S( RITS I.ITTKRAIRKS FRANC AIS 1)1 XXe SIF.C IT : C ()NTEX I F. I I MISF I N PI.AC F DTN RFPFRIOIRF, DF l.CX ALISATION Catherine ELOI Stage effectue au Departement des Manuscrits de ia Bibliotheque nationale de France sous la responsabilite de Madame Annie Angremy 995 J)d£> REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens a remercier tout le personnel du Departement des Manuscrits pour sa gentillesse et sa disponiblite et tout particulierement Gilles Cugnon, Christelle Bourguignat et William Marx qui m'ont fourni la documentation et les renseignements necessaires a Felaboration de mon memoire. Je tiens egalement a remercier les conservateurs du Departement qui ont tous bien voulu m'accorder regulierement un peu de leur temps et particulierement Florence Callu et Annie Angremy qui dirigea mon stage. RESUME L'interet grandissant des scientifiques ainsi que d'un plus large public pour les manuscrits iitteraires entraine un developpement des recherches a ce sujet, Le manuscrit litteraire moderne privilegie plusieurs approches : la conservation, la recherche litteraire, la mise en valeur tant sur le plan de 1'edxtion que sur celui des expositions. -

Thomas Hardy, the Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, (Ed.) Michael Drama and the Theatre: the Dynasts' and 'The Famous Tragedy of Th

Notes Notes to the Introduction 1. Thomas Hardy, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, (ed.) Michael Millgate (London, Macmillan, 1984; Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985) p. 56. Hereafter cited as Life and Work. 2. While this is the first full-length study of Hardy's interest and involvement in the theatre, it takes its place within the small but solid body of scholarship that has appeared since Marguerite Roberts first addressed two specific aspects of the subject in her books Tess in the Theatre (University of Toronto Press, 1950) and Hardy's Poetic Drama and the Theatre: The Dynasts' and 'The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall' (New York: Pageant Press, 1965). Other significant contributions are David N. Baron, 'Harry Pouncy and the Hardy Players', Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset, 31 (September 1980) pp. 45-50 and his 'Hardy and the Dorchester Pouncys- Part Two', Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset, 31 (September 1981) pp. 129-35; Harold Orel, 'Hardy and the Theatre', in Margaret Drabble (ed.), The Genius of Thomas Hardy (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1976) pp. 94-108, and 'Hardy's Interest in the Theatre' in Harold Ore!, The Unknown Thomas Hardy (Brighton: Harvester, 1987) pp. 37--{;6; Desmond Hawkins's very helpful checklist of dramatiza tions, which forms an appendix (pp. 225-36) to his Hardy, Novelist and Poet (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1976); and Joan Grundy's 'Theatrical Arts', in her Hardy and the Sister Arts (London: Macmillan, 1979) pp. 70-105. Mention should also be made of Vincent Tollers's useful unpublished doctoral dissertation, 'Thomas Hardy and the Professional Theatre, with Emphasis on The Dynasts' (University of Colorado, 1968) and James Stottlar's 'Hardy vs. -

Autumn 2018 Journal

THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL THOMAS HARDY THE THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL VOL XXXIV VOL AUTUMN AUTUMN 2018 VOL XXXIV 2018 A Thomas Hardy Society Publication ISSN 0268-5418 ISBN 0-904398-51-X £10 ABOUT THE THOMAS HARDY SOCIETY The Society began its life in 1968 when, under the name ‘The Thomas Hardy Festival Society’, it was set up to organise the Festival marking the fortieth anniversary of Hardy’s death. So successful was that event that the Society continued its existence as an organisation dedicated to advancing ‘for the benefit of the public, education in the works of Thomas Hardy by promoting in every part of the World appreciation and study of these works’. It is a non-profit-making cultural organisation with the status of a Company limited by guarantee, and its officers are unpaid. It is governed by a Council of Management of between twelve and twenty Managers, including a Student Gerald Rickards Representative. Prints The Society is for anyone interested in Hardy’s writings, life and times, and it takes Limited Edion of 500 pride in the way in which at its meetings and Conferences non-academics and academics 1.Hardy’s Coage have met together in a harmony which would have delighted Hardy himself. Among 2.Old Rectory, St Juliot its members are many distinguished literary and academic figures, and many more 3.Max Gate who love and enjoy Hardy’s work sufficiently to wish to meet fellow enthusiasts and 4.Old Rectory, Came develop their appreciation of it. Every other year the Society organises a Conference that And four decorave composions attracts lecturers and students from all over the world, and it also arranges Hardy events featuring many aspects of Hardy’s not just in Wessex but in London and other centres. -

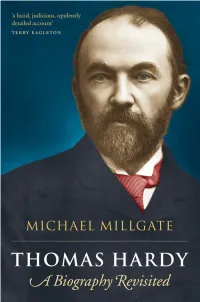

Thomas-Hardy-A-Biography-Revisited-Pdfdrivecom-45251581745719.Pdf

THOMAS HARDY This page intentionally left blank THOMAS HARDY MICHAEL MILLGATE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 2 6 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Michael Millgate 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 First published in paperback 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Antony Rowe, Chippenham ISBN 0–19–927565–3 978–0–19–927565–6 ISBN 0–19–927566–1 (Pbk.) 978–0–19–927566–3 (Pbk.) 13579108642 To R.L.P. -

Moments of Vision Exhibition Catalogue

Hardy g17_Layout 1 16-10-20 5:05 PM Page 1 ‘oments of ision’ e Life and Work of Thomas Hardy Exhibition and Catalogue by Debra Dearlove, with Contributions by Keith Wilson and Deborah Whiteman, and a Biographical Introduction by Michael Millgate. The Thomas Fisher rare Book LiBrary, UniversiTy oF ToronTo 24 October 2016 – 24 February 2017 Hardy g17_Layout 1 16-10-20 5:05 PM Page 2 Catalogue and exhibition by Debra Dearlove with contributions by Keith Wilson and Deborah Whiteman Biographical Introduction by Michael Millgate Editors P.J. Carefoote and Philip Oldfield Exhibition designed and installed by Linda Joy Digital Photography by Paul Armstrong Catalogue designed by Stan Bevington Catalogue printed by Coach House Press Cover illustration, see item 16. Endpapers from item 133. LiBrary and archives canada caTaLogUing in pUBLicaTion omas Fısher Rare Book Library, issuing body, host institution ‘Moments of vision’ : the life and work of omas Hardy / exhibition and catalogue by Debra Dearlove, with contributions by Keith Wilson and Deborah Whiteman, and a biographical introduction by Michael Millgate. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the e omas Fısher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, from October 24, 2016 to February 24, 2017. Includes bibliographical references. isBn 978-0-7727-6120-0 (paperback) 1. omas Fısher Rare Book Library – Exhibitions. 2. Millgate, Michael – Private collections – Ontario – Toronto – Exhibitions. 3. Hardy, omas, 1840–1928 – Bibliography – Exhibitions. 4. Authors, English – 19th century – Biography – Exhibitions. i. Dearlove, Debra, 1959-, author ii. Wilson, Keith (Keith G.), author iii. Whiteman, Deborah, author iv. Millgate, Michael, writer of introduction V. Title. pr4753.T48 2016 823'.8 c2016-905988-X Hardy g17_Layout 1 16-10-20 5:05 PM Page 3 Table of Contents Foreword 4 In memory of David J. -

Download Complete Issue

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society founded in 1899, the Presbyterian Historical Society of England, founded in 1913, and the Churches of Christ Historical Society, founded in 1979) EDITOR: PROFESSOR CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 8 No 5 November 2009 CONTENTS Editorial and Notes ............................................ 244 Missionaries to Lancashire and Beyond: the Dawsons of Aldcliffe by Nigel Lemon ........................................ 245 Geoffrey Nuttall in Conversation by Geoffrey Nuttall, edited and with a postscript by Alan P.F Sell ........................................ 266 The Casterbridge Congregationalists by John Travel/ ......................................... 291 Reviews by C. Keith Forecast, Alan Sell, and Martin We/lings ........... 306 244 EDITORIAL This issue is deceptively representative. It focuses on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries but it reaches back to the seventeenth century. It is Anglocentric but Wales and Scotland play more than walk-on roles. It is primarily Congregational but it draws from English Presbyterianism and it feeds suggestively into the United Reformed Church. More suggestively yet, it shows how what is apparently peripheral, or more certainly localised, eccentric, or exceptional, is in fact representative. Today's inheritors of the Reformed tradition need to be quite as aware of that as today's supposedly more objective historians. The Dawsons of Aldcliffe, for example, were excep tional in their sustained prosperity but there was not an aspect of contemporary Congregationalism which their lives did not touch or illuminate. Chapel thespians are footnotes at best even in the best chapel histories but Dorchester's Hardy Players shed light on many interconnexions in chapel culture. Theirs is the world which in differing circumstances produced Jerome K. -

Introduction 1867-1893

INTRODUCTION I. HARDY AND THE THEATRE, 1867-1893 THE drama appealed to Thomas Hardy. Like Keats he wanted to write a few fine plays. Apart from lyric poetry Hardy's earliest literary aspiration lay in the field of poetic drama. His interest in contributing to the theatre extended over a period of nearly sixty years, from 1867, when he first considered writing for the stage, until 1926, when he still desired to see Jude the Obscure dramatized. Although, as Mrs. Hardy reminded me, most people do not think of Hardy as a dramatist, his private papers reveal the fact that there were times when he was interested in writing drama not only to be read but also for the stage. At certain times this attraction to the theatre was especially strong; but unfortunately at these crucial moments he was repulsed, frustrated, and turned in some other direction either by the advice of a friend, the conditions of the contemporary stage, or the break-down of negotiations with actors and managers. As a result Hardy never devoted his full energy to the practical art of writing plays. But, despite that, his interest in the folk-drama of Wessex, and in the Greek and Elizabethan tragedy, as well as in the current productions of the London stage, is marked in varying degrees throughout his long life. And his correspondence with actors, managers, and dramatic critics, as revealed in this study, shows that his attitude toward his own work in the theatre varies from indifference to enthusiasm. In 1867, Hardy had formed the idea of writing drama in blank verse and planned to make a first-hand study of the theatre for six or twelve months from the vantage-point of a supernumerary. -

'Moments of Vision': the Life and Work of Thomas Hardy

‘Moments of Vision’: The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy ‘Moments of Vision’: The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto 24 October 2016–24 February 2017 SHARP News https://www.sharpweb.org/sharpnews/ | 1 ‘Moments of Vision’: The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy The Thomas Fisher Library’s latest exhibit, ‘Moments of Vision’: The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, curated by the renowned Canadian Rare Book dealer Debra Dearlove, and with contributions from Keith Wilson, Deborah Whiteman, and Michael Millgate, celebrates what can be described modestly as one of the most substantial literary donations to the Library of SHARP News https://www.sharpweb.org/sharpnews/ | 2 ‘Moments of Vision’: The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy the past 25 years: As Interim Director of the Fisher, Loryl MacDonald, writes in her Foreword to the catalogue, “[t]he basis…is the superb Millgate Thomas Hardy Collection, gifted to the Library by Jane and Michael Millgate in 2012 and in 2013…assembled by Michael Millgate over forty-five years” (4).With this gift, which was “prior to its donation…acknowledged as the largest and most comprehensive Hardy collection outside of a public institution” (4), the Fisher Library is “now a leading Hardy repository” (5). Bringing together 175 items not only from the Millgate donation but from Dearlove’s personal collection, and with reproduced surrogates from five institutions, the exhibition’s biggest strength is in calling attention to the visual traditions and artistry associated with the great Thomas Hardy’s well-chosen words. -

'The Warfare of Our Higher and Our Lower Selves

‘The warfare of our higher and our lower selves’: an analysis of the relationship between mental illness and artistic creativity through a case study of Thomas Hardy’s cyclothymic tendencies by Kate Suzanne O’Connor B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2012 © Kate Suzanne O’Connor, 2012 Abstract In July of 2008, scholar Tony Fincham offered a retrospective diagnosis of cyclothymia, a milder variant of manic-depression, in explanation of Thomas Hardy’s seemingly cyclical bouts of depression and mania. In preparation of the depressive component of this diagnosis, Fincham consulted four sources - one that fully documents letters written by Thomas Hardy, two that partially document Hardy’s notebook entries, and one that publishes scholarly essays on the author and his works. Fincham located a total of forty incidents within these four sources that describe Hardy as suffering from episodes of depression. Conversely, in an effort to locate instances of mania, Fincham collected only three examples from two different sources, one in a letter written by Florence Hardy and two in Michael Millgate’s 1982 Thomas Hardy: A Biography. This study is useful as it provides an introductory explanation for the mood swings so prevalent in letters and accounts of Hardy’s life, however, having only consulted five sources, it is most definitely not a thorough analysis of the extent to which Hardy may have been suffering from cyclothymia. -

Research Realism in the Novel of Thomas Hardy

North American Academic Research Journal homepage: http://twasp.info/journal/home Research Realism in the Novel of Thomas Hardy Mst. Nilufar Yasmin1, Rafi Imam2 1Department of English, Uttara University, Bangladesh 2Professor, Department of English, Uttara University, Bangladesh *Corresponding author Accepted: 05 November, 2019; Online: 09 November, 2019 DOI : https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3533971 Abstract: Fundamental to Thomas Hardy's fiction and verse, just as his memoir, scenes of move continually sanction characters' connections to history and memory and investigate the phenomenology of volition and of self-misfortune. A full range of sociality exists crosswise over such moves, from delighted collectivity to sorrowful self-antagonism, concentrated romance to private joy. Solid investigates moving additionally for its affinities with work, engineering and battle. The differently danceable rhythms of his productive, metrically aspiring stanza enlighten what the essayist's praised inspirations of time may owe to move. In a few of the books, move prompts iridescent dialects of tangible surface and populates elucidating sections with a thickness and dynamism that may represent Hardyean authenticity at its generally test. Close literary examination, move hypothesis and neurophysiology propose that Hardy's moves may transform stationary adding something extra to a method of mimetic and kinaesthetic vision – a demonstration of moving by different implies. Keywords: Thomas Hardy, fiction, verse T HE NOVELS, STORIES AND POEMS of Thomas Hardy teem with dance descriptions unrivalled in intricacy and variety among major English writers. The distinct purposes and poetics of this persistent Hardyean motif have received scant critical attention, however, even as – or indeed because – the author's own childhood immersion in music and dance is routinely checked off as a stock biographical fact, rather than peered into through his writing. -

Music Inspired by the Works of Thomas Hardy

This article was first published in The Hardy Review , Volume XV-ii, Autumn 2013, pp. 37-52, and is reproduced by kind permission of The Thomas Hardy Association, editor Rosemarie Morgan. Should you wish to purchase a copy of the paper please go to: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ttha/thr/2013/00000015/0 0000002/art00005 LITERATURE INTO MUSIC: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE WORKS OF THOMAS HARDY Part One: Music composed during Hardy’s lifetime CHARLES P. C.PETTIT Many of the most notable British composers of Hardy's later years wrote music inspired by his writings. This article concentrates on music by those composers who wrote operatic and orchestral works during Hardy's lifetime, and only mentions song settings of poems, and music in dramatisations for radio and other media, when they were written by featured composers. An article to be published in the next issue of The Hardy Review will consider more recent compositions. Detailed consideration is given to three major works: Frederic d'Erlanger's Tess , Rutland Boughton's The Queen of Cornwall and Gustav Holst's Egdon Heath . Shorter evaluations follow of Hardy-influenced works by Patrick Hadley, H. Balfour Gardiner, Ralph Vaughan Williams and John Ireland. There is a note on a projected collaboration with Sir Edward Elgar that never came to fruition. In conclusion there is a brief appraisal of why Hardy's works should have had such an appeal to composers of that era. Keywords : Thomas Hardy, Music, Frederic d'Erlanger, Rutland Boughton, Gustav Holst, Patrick Hadley, H. Balfour Gardiner, Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, Sir Edward Elgar Studies of Hardy and music have tended, understandably enough, to concentrate on the music that influenced Hardy or the part played by music in Hardy’s works, rather than on the music that Hardy inspired.