Introduction 1867-1893

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Fate and Nature and the Creation of Tragic Sense in Some of Hardy's

ADAB AL-RAFIDAYN vol. (46) 1428 / 2007 Fate and Nature and the Creation of Tragic Sense in Some of Hardy’s Novels Ra’ad Ahmed Saleh(*) & Huda M. Saleh The indifference and hostility of Fate and Nature are the characterstic common in Hardy’s novels; inevitable suffering overwhelms the life of the character in Hardy’s novels. In his novels Fate and Nature rule the world of his novels. The hero’s desire for happiness collapses into terrible misery. Such an atmosphere makes Hardy’s novels of close relation to tragedies in the Greek sense. This means that Hardy’s novels can be considered the successors to the tragedies of the Greek, of Shakespeare and Marlowe before him. There are indications in the novels themselves that Hardy was attemping, in novel form, to present tragedies in the old model of Greek drama(1). (*)Assist. Professor Dept of English-College of Arts / University of Mosul. 37 Fate and Nature and the Creation of Tragic...... Ra’ad Ahmed Saleh & Huda M. Saleh It can be said of The Return of the Native, Tess of the D’Urbervills and The Mayor of Casterbridge that they conform to Aristotles’s definition of tragedies which is found in chapter six of his Poetics. He difined tragedy as: The imitation of an action that is serious, has magnitude, and is complete in itself in laguage with pleasurable accessories, each kind brought in separately in the various of the work; in a dramatic not in narrative form; with incidents arousing our pity and fear(2) Some people might feel discomfort to find novels compared to tragic play because they are written in narrative form. -

Irving Room David Garrick (1717-1779) Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811) (After) Oil on Canvas BORGM 00609

Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Irving Room David Garrick (1717-1779) Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811) (after) Oil on canvas BORGM 00609 Landscape with a Cow by Water Joseph Jefferson (1829-1905) Oil on canvas BORGM 01151 Sir Henry Irving William Nicholson Print Irving is shown with a coat over his right arm and holding a hat in one hand. The print has been endorsed 'To My Old Friend Merton Russell Cotes from Henry Irving'. Sir Henry Irving, Study for ‘The Golden Jubilee Picture’, 1887 William Ewart Lockhard (1846-1900) Oil in canvas BORGM 01330 Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Sir Henry Irving in Various Roles, 1891 Frederick Barnard (1846-1896) Ink on paper RC1142.1 Sara Bernhardt (1824-1923), 1897 William Nicholson (1872-1949) Woodblock print on paper The image shows her wearing a long black coat/dress with a walking stick (or possibly an umbrella) in her right hand. Underneath the image in blue ink is written 'To Sir Merton Russell Cotes with the kind wishes of Sara Bernhardt'. :T8.8.2005.26 Miss Ellen Terry, Study for ‘The Golden Jubilee Picture’, 1887 William Ewart Lockhart (1846-1900) Oil on canvas BORGM 01329 Theatre Poster, 1895 A theatre poster from the Borough Theatre Stratford, dated September 6th, 1895. Sir Henry Irving played Mathias in The Bells and Corporal Brewster in A Story of Waterloo. :T23.11.2000.26 Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Henry Irving, All the World’s a Stage A print showing a profile portrait of Henry Irving entitled ‘Henry Irving with a central emblem of a globe on the frame with the wording ‘All The World’s A Stage’ :T8.8.2005.27 Casket This silver casket contains an illuminated scroll which was presented to Sir Henry Irving by his friends and admirers from Wolverhampton, in 1905. -

Manuscrits Littéraires Français Du Xxè Siècle

Ecole Nationale Superieure des Sciences de 1'information et des bibliotheques Diplome de conservateur de bibliotheque MEMOIRE D'ETUDE LES MAM S( RII S I.ITTKRAIRF.S FRANO AIS DV \\c SIFCl.F : C ONTF\TF F! MfSF E\ PLACF DTN RFPFRTOIRF DF LOCALISA 1ION Catherine ELOI Sous la direction de Madame Dominique BOUGE-GRANDON ENSSIB 1995 Ecole Nationale Superieure des Sciences de 1'information et des bibliotheques Diplome de conservateur de bibliotheque MEMOiRE D'ETUDE LF.S MAM S( RITS I.ITTKRAIRKS FRANC AIS 1)1 XXe SIF.C IT : C ()NTEX I F. I I MISF I N PI.AC F DTN RFPFRIOIRF, DF l.CX ALISATION Catherine ELOI Stage effectue au Departement des Manuscrits de ia Bibliotheque nationale de France sous la responsabilite de Madame Annie Angremy 995 J)d£> REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens a remercier tout le personnel du Departement des Manuscrits pour sa gentillesse et sa disponiblite et tout particulierement Gilles Cugnon, Christelle Bourguignat et William Marx qui m'ont fourni la documentation et les renseignements necessaires a Felaboration de mon memoire. Je tiens egalement a remercier les conservateurs du Departement qui ont tous bien voulu m'accorder regulierement un peu de leur temps et particulierement Florence Callu et Annie Angremy qui dirigea mon stage. RESUME L'interet grandissant des scientifiques ainsi que d'un plus large public pour les manuscrits iitteraires entraine un developpement des recherches a ce sujet, Le manuscrit litteraire moderne privilegie plusieurs approches : la conservation, la recherche litteraire, la mise en valeur tant sur le plan de 1'edxtion que sur celui des expositions. -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository: a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Phd at The

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36168 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Critical and Popular Reaction to Ibsen in England: 1872-1906 by Tracy Cecile Davis Thesis supervisors: Dr. Richard Beacham Prof. Michael R. Booth Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Warwick, Department of Theatre Studies. August, 1984. ABSTRACT This study of Ibsen in England is divided into three sections. The first section chronicles Ibsen-related events between 1872, when his work was first introduced to a Briton, and 1888, when growing interest in the 'higher drama' culminated in a truly popular edition of three of Ibsen's plays. During these early years, knowledge about and appreciation of Ibsen's work was limited to a fairly small number of intellectuals and critics. A matinee performance in 1880 attracted praise, but successive productions were bowdlerized adaptations. Until 1889, when the British professional premiere of A Doll's House set all of London talking, the lack of interest among actors and producers placed the responsibility for eliciting interest in Ibsen on translators, lecturers, and essayists. The controversy initiated by A Doll's House was intensified in 1891, the so-called Ibsen Year, when six productions, numerous new translations, debates, lectures, published and acted parodies, and countless articles considered the value and desirability of Ibsen's startling modern plays. -

Thomas Hardy, the Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, (Ed.) Michael Drama and the Theatre: the Dynasts' and 'The Famous Tragedy of Th

Notes Notes to the Introduction 1. Thomas Hardy, The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, (ed.) Michael Millgate (London, Macmillan, 1984; Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985) p. 56. Hereafter cited as Life and Work. 2. While this is the first full-length study of Hardy's interest and involvement in the theatre, it takes its place within the small but solid body of scholarship that has appeared since Marguerite Roberts first addressed two specific aspects of the subject in her books Tess in the Theatre (University of Toronto Press, 1950) and Hardy's Poetic Drama and the Theatre: The Dynasts' and 'The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall' (New York: Pageant Press, 1965). Other significant contributions are David N. Baron, 'Harry Pouncy and the Hardy Players', Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset, 31 (September 1980) pp. 45-50 and his 'Hardy and the Dorchester Pouncys- Part Two', Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset, 31 (September 1981) pp. 129-35; Harold Orel, 'Hardy and the Theatre', in Margaret Drabble (ed.), The Genius of Thomas Hardy (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1976) pp. 94-108, and 'Hardy's Interest in the Theatre' in Harold Ore!, The Unknown Thomas Hardy (Brighton: Harvester, 1987) pp. 37--{;6; Desmond Hawkins's very helpful checklist of dramatiza tions, which forms an appendix (pp. 225-36) to his Hardy, Novelist and Poet (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1976); and Joan Grundy's 'Theatrical Arts', in her Hardy and the Sister Arts (London: Macmillan, 1979) pp. 70-105. Mention should also be made of Vincent Tollers's useful unpublished doctoral dissertation, 'Thomas Hardy and the Professional Theatre, with Emphasis on The Dynasts' (University of Colorado, 1968) and James Stottlar's 'Hardy vs. -

International Theatre Programs Collection O-018

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8b2810r No online items Inventory of the International Theatre Programs Collection O-018 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis General Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/special-collections/ Inventory of the International O-018 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-018 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis General Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: International Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-018 Physical Description: 19.1 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1884-2011 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century British programs, including a sizable group from Dublin's Abbey Theatre. Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents The collection includes mostly 19th and early 20th century British programs, including a sizable group from Dublin's Abbey Theatre. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], International Theatre Program Collection, O-018, Department of Special Collections, General Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items. -

T7^ Journal of the Rutgers University Library

T7^ JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY VOLUME XIII DECEMBER 1949 NUMBER I SOME LETTERS ON HARDY'S 'TESS' BY CARL J. WEBER Roberts Professor of English Literature at Colby Collegey in Watervilley Mainey Dr. Weber is the author of Hardy of Wessex: A Critical Biography (Columbia University Press, 1Q40) and of Hardy in America (Colby College Press} iQ4Ô)y and is the comfiler of The First Hundred Years of Thomas Hardy, a C5ntennial bibliografhy. N the J. Alexander Symington Collection of letters and manu- scripts now in the Rutgers University Library,1 there are four Iholographs that recall an exciting period in late-Victorian days when everyone in the world—at least in the literary world—was reading Tess of the D'Urbervilles. On the first day of January in 1892, Edmund Gosse wrote to Thomas Hardy: "Your book [Tess] is simply magnificent and wherever I go I hear its praises. Your success has been phenome- nal." Soon, however, the heavenly radiance of this success faded into the light of common day 3 for on January 16 the Saturday Review published a bitter attack on Tess and Hardy's head was soon bloody. In Chapter 25 of his novel he had remarked: "The magnitude of lives is not as to their external displacements, but as to their subjective experiences. The impressionable peasant leads a larger, fuller, more dramatic life than the pachydermatous king." Even before 1892 Hardy had showed himself to be, albeit a king of novelists, by no means a pachydermatous one. And the events of 1892 did not change him. -

The Archive of American Journalism H.L. Mencken Collection Baltimore

The Archive of American Journalism H.L. Mencken Collection Baltimore Evening Sun April 23, 1910 William Shakespeare Stratford-on-Avon, that sleepy old town, is as crowded and lively just now as a Chesapeake excursion boat on the Fourth of July, for today is the birthday of William Shakespeare, and thousands of tourists have flocked to his birthplace to see the festival performances in the Shakespeare Theatre. This year’s festival will last not the usual two weeks, but a full month, and all the English actors, including Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Lewis Waller and Sir John Hare, will have some hand in it. That April 23 is Shakespeare’s birthday is nothing more than a convenient assumption, for no one really knows when he was born. All that the most painstaking research has been able to discover is that he was baptized on April 26, 1564. It was the general custom in those days to have a child baptized three days after birth, and so it is assumed that the greatest of all dramatists first saw the light on April 23. To be strictly accurate, we should really celebrate his birthday on May 3, for he was born while the old style, or Julian, calendar was still in force, and there is a difference of 10 days between that calendar and the one now in use. The change was made by Pope Gregory XIII in October, 1382, when Shakespeare was 18 years old. To correct the error that the old calendar, with its few minutes loss of time every year had brought about in the course of centuries Gregory decreed that October 5, 1582, should be called October 15. -

Mrs. Patrick Campbell, Caesar in Ccarsnr Or~Rlclcopatrn for Forbes Robertson, and Lady Cicely in Captain Brassbot~~Rd'j Cor~~,Crsiorlfor Ellen Terry

This document is from the Cornell University Library's Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections located in the Carl A. Kroch Library. If you have questions regarding this document or the information it contains, contact us at the phone number or e-mail listed below. Our website also contains research information and answers to frequently asked questions. http://rmc.library.cornell.edu Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections 2B Carl A. Kroch Library Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Phone: (607) 255-3530 Fax: (607) 255-9524 E-mail: [email protected] This publication has been prepared with the generous support of the Arnold '44 and Gloria Tofias Fund and the Bernard E Burgunder Fund for George Bernard Shaw. + Issued on the Occasion of "77re Instinct of an Artist:" Straw and the Theatre. An Exhibition from the Bernard F. Hurgunder Collection of George Bernard Shaur, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections Carl A. Kroch Library April 17-June 13,1997 Cover and lnsidc Cover Illustrations: Shown are Shaw's photographic postcards sent to actress Evlarparet Halstan, critiquin~her performance as Raina in Arnold Dnly's ign revival of Annr and the )Man. [Item iA] Title page illustration by Antnny Wysard Note: Shaw ohcn spelled words phonetically, and sometimes used archaic forms of words. In quoting Shaw, we have retained his unusual spelling throughout O 1997 Cornell University Library The Instinct of an Artist + he Bernard F. Burgunder Collection of George Bernard Shaw was established at Cornell University in 1956, the centennial of Shaw's birth. The Collection repre- T sents a lifelong enthusiasm of the donor, Bernard Rurgundcr, who began collect- ing Shaviana soon after his graduation from Cornell in 1918. -

Autumn 2018 Journal

THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL THOMAS HARDY THE THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL VOL XXXIV VOL AUTUMN AUTUMN 2018 VOL XXXIV 2018 A Thomas Hardy Society Publication ISSN 0268-5418 ISBN 0-904398-51-X £10 ABOUT THE THOMAS HARDY SOCIETY The Society began its life in 1968 when, under the name ‘The Thomas Hardy Festival Society’, it was set up to organise the Festival marking the fortieth anniversary of Hardy’s death. So successful was that event that the Society continued its existence as an organisation dedicated to advancing ‘for the benefit of the public, education in the works of Thomas Hardy by promoting in every part of the World appreciation and study of these works’. It is a non-profit-making cultural organisation with the status of a Company limited by guarantee, and its officers are unpaid. It is governed by a Council of Management of between twelve and twenty Managers, including a Student Gerald Rickards Representative. Prints The Society is for anyone interested in Hardy’s writings, life and times, and it takes Limited Edion of 500 pride in the way in which at its meetings and Conferences non-academics and academics 1.Hardy’s Coage have met together in a harmony which would have delighted Hardy himself. Among 2.Old Rectory, St Juliot its members are many distinguished literary and academic figures, and many more 3.Max Gate who love and enjoy Hardy’s work sufficiently to wish to meet fellow enthusiasts and 4.Old Rectory, Came develop their appreciation of it. Every other year the Society organises a Conference that And four decorave composions attracts lecturers and students from all over the world, and it also arranges Hardy events featuring many aspects of Hardy’s not just in Wessex but in London and other centres. -

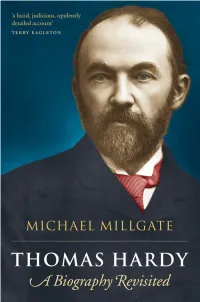

Thomas-Hardy-A-Biography-Revisited-Pdfdrivecom-45251581745719.Pdf

THOMAS HARDY This page intentionally left blank THOMAS HARDY MICHAEL MILLGATE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 2 6 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Michael Millgate 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 First published in paperback 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Antony Rowe, Chippenham ISBN 0–19–927565–3 978–0–19–927565–6 ISBN 0–19–927566–1 (Pbk.) 978–0–19–927566–3 (Pbk.) 13579108642 To R.L.P.